Jessica He, University of Warwick

This study explores the experiences of first-generation students at Warwick University, focusing on academic preparedness, financial barriers, social integration and mentorship support. The research specifically compares the experiences of students who were and were not part of the Warwick Scholars Programme, revealing that both groups faced similar challenges. Existing literature highlights challenges faced by first-generation students, including deficiencies in academic preparation, financial constraints and social isolation. Using a mixed-methods approach, this paper combines survey data (N = 24) with in-depth interviews (N = 4) to provide a comprehensive understanding of these issues. The findings reveal that both Warwick Scholars and non-Scholars experience similar levels of under-preparedness, despite pre-university interventions. Financial pressures significantly influence educational choices and contribute to family-driven stress. Social integration varies, with some students feeling isolated while others find community through extracurricular activities. Mentorship support is inconsistent, with some students benefitting from personal tutors and peer networks while others struggle to access adequate guidance. The study underscores the necessity for more inclusive and targeted support systems to address the multifaceted challenges faced by first-generation students. While the paper provides valuable insights, limitations include a small sample size, suggesting the need for broader studies. Key recommendations include increasing counselling and skill-building workshops, expanding financial aid, and enhancing mentorship, guidance and career support to better support first-generation students.

Keywords: First-generation students in UK higher education, Academic preparedness of first-generation university students, Financial pressures on first-generation students, Social integration in higher education, Mentorship support for first-generation students, Warwick Scholars Programme.

First-generation or ‘First in Family’ (FiF) students – typically defined as those whose parents or guardians have not attained a university-level degree (BA/BSc or higher) – represent a growing and important demographic in UK higher education (Adamecz-Völgyi et al., 2020; Henderson et al., 2020). More precisely, a young person is considered FiF if neither parent nor guardian had achieved a university degree by the time the student was aged 17 – namely, before their university application (Adamecz-Völgyi et al., 2020). Much of the literature on first-generation experiences is US-centric, and UK-based research remains limited, particularly in terms of quantitative and institution-specific studies (Henderson et al., 2020).

This study addresses that gap by examining the academic, financial and social experiences of first-generation students at a UK Russell Group university. It is situated at the University of Warwick and contributes to the growing body of UK-focused research on Widening Participation (WP). While grounded in Warwick’s context, the findings and recommendations are relevant to other selective institutions with similar WP responsibilities.

The aim of this paper is to explore the lived experiences of first-generation students and offers actionable insights to enhance access to institutional support networks. A central focus of this research is the comparison between Warwick Scholars and non-Scholars. The Warwick Scholars Programme is a targeted WP initiative that supports students from underrepresented backgrounds – including those from lower-income households, care-experienced or estranged backgrounds, and priority neighbourhoods (University of Warwick, 2025). In contrast, the non-Scholars in this study are also first-generation students but they did not receive support through this programme. Comparing these two groups allows for an evaluation of whether structured pre-university interventions translate into improved student outcomes and experiences.

First-generation students, regardless of programme participation, often face overlapping challenges such as financial constraints, unfamiliarity with university culture and limited access to guidance or resources (Pascarella et al., 2004; Thomas, 2006). While institutional support services – such as academic advising and financial aid guidance – can improve outcomes (Wainwright and Watts, 2019), access to and effectiveness of such support vary significantly across student populations.

To investigate these issues, this study is guided by two overarching research questions:

A mixed-methods approach was employed, combining quantitative survey data from 24 first-generation WP students (12 Warwick Scholars and 12 non-Scholars) and qualitative insights from semi-structured interviews (N = 4) to capture both breadth and depth. The survey included an additional six respondents who were not classified as WP students, but they are excluded from this comparative analysis. Participants were recruited through student networks, academic departments and WP initiatives, with eligibility based on self-identification as first-generation and confirmation of participation (or not) in the Warwick Scholars Programme. These research questions were further broken down into sub questions (see Table 1).

Table 1: Research questions

Research questions |

Sub-questions |

Data source |

How do first-generation students at the University of Warwick navigate academic, financial and social challenges in their university experience? |

1.1 How do first-generation Warwick Scholars perceive their academic preparedness compared to non-Scholars? |

Survey (Likert scale): I felt academically prepared for university. Interview: Can you describe the academic skills and knowledge you acquired before starting university? How did this preparation affect your confidence in your academic abilities? |

1.2 What are the specific challenges faced by first-generation students in transitioning to university-level studies? |

Survey (Likert scale): I have faced significant challenges as a first-generation student. Interview: What, if any, challenges have you faced that you feel are related to being a first-generation student? Which are the biggest challenges? |

|

1.3 To what extent do financial considerations influence education choices among first-generation students? |

Survey (Likert scale): Financial considerations have significantly impacted my educational choices. Interview: How have financial considerations impacted your educational choices? |

|

1.4 How do family financial dynamics affect academic experiences of first-generation students at Warwick? |

Survey (Likert scale): My family has provided substantial support for my higher education journey. Interview: In what ways has your family supported or influenced your journey in higher education? |

|

1.5 How do first-generation students perceive their sense of belonging at Warwick University? |

Survey (Likert scale): I feel a strong sense of belonging within the university community. Interview: Can you share your experiences with social integration at university? Have you felt a sense of belonging within the academic community? |

|

1.6 What roles does cultural background play in shaping university experiences of first-generation students? |

Survey: My cultural background has significantly influenced my university experience. Interviews: In what ways has your cultural background shaped your experiences at university? |

|

What roles do institutional support and mentorship programmes play in the academic success and well-being of first-generation students? |

2.1 How effective are mentorship programmes in supporting academic success among first-generation students? |

Survey: I have had access to effective mentorship or peer support networks. Interview: Have you had access to mentorship or peer support networks? How have these influenced your academic journey? |

2.2 What are the perceptions of Warwick Scholars and non-Scholars regarding access to support services? |

Survey: The academic support services at the university have met my needs. Interview: What types of academic support services have you utilised, and how effective have they been for you? How well do you think the university supports first-generation students? |

The structure of this paper begins with a literature review on first-generation student experiences, followed by the presentation and analysis of the survey and interview findings. Through this research, I highlight both the barriers and opportunities encountered by first-generation students at Warwick, contributing to the development of more inclusive and effective institutional support systems.

This literature review explores the barriers faced by first-generation or ‘First in Family’ (FiF) students in higher education and examines how these challenges shape their academic engagement, social integration and access to institutional support. The review is organised into thematic subheadings, each providing a focused discussion on key issues identified in the literature and forming the basis upon which this study builds.

First-generation students often arrive at university with limited academic preparation and are more likely to be non-native English speakers, immigrants and financially independent (Bui, 2002; Jehangir, 2010, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013). This under-preparedness contributes to lower confidence and hesitancy in seeking help from faculty (Katrevich and Aruguete, 2017; Pascarella et al., 2004), particularly when navigating academic expectations such as assignment requirements, academic writing structures and exam standards – areas that reflect a lack of cultural capital (Thomas, 2006). Consequently, the transition to university can be overwhelming, especially when institutional resources feel unfamiliar or inaccessible (Forsyth and Furlong, 2003, cited in Thomas, 2006; Stebleton and Soria, 2013). These challenges are further intensified for students who must work – often full-time – to meet living or tuition costs, limiting the time they can devote to study and academic engagement (Jehangir, 2010, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013).

Financial pressures are a recurring barrier in the literature, with many first-generation students balancing academic demands with full-time employment (Bui, 2002; Thomas, 2006). Family responsibilities can further constrain their engagement, particularly for those expected to support relatives or serve as role models for younger siblings (Jehangir, 2010, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013; Wainwright and Watts, 2019). Additionally, living off campus and time constraints from work or caregiving reduce opportunities for peer interaction and on-campus involvement (Pascarella et al., 2004, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013). These factors collectively undermine academic focus and emotional support systems essential for student persistence (Thomas, 2006).

Beyond financial and academic barriers, first-generation students often face cultural dissonance as they navigate between home and university environments. The contrast between familial expectations and institutional norms can lead to identity fragmentation and a weakened sense of belonging (Oldfield, 2007; Rendón, 1992, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013). London (1989, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013) emphasises that these transitions are not only academic but also deeply social and cultural, often resulting in feelings of isolation, depression and loneliness (Lippincott and German, 2007, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013).

Peer support and integration are critical to student retention (Thomas, 2006), yet first-generation students – particularly those living at home or from diverse socio-cultural backgrounds – frequently struggle to integrate into university life. A mismatch between their home culture and university norms can hinder both academic engagement and social participation (Adamecz-Völgyi et al., 2020; Forsyth and Furlong, 2003, cited in Thomas, 2006). These integration barriers highlight the limited social and cultural capital many first-generation students possess (Wainwright and Watts, 2019; Thomas, 2006), compounding their sense of disconnection in both settings.

These combined challenges – academic under-preparation, financial strain and social isolation – contribute to lower persistence and graduation rates among first-generation students (Engle and Tinto, 2008, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013; Stebleton and Soria, 2013). Despite being well-positioned to benefit from high-impact educational practices such as learning communities and study abroad programmes, these students are less likely to participate due to limited awareness, time or access (Jehangir, 2010 cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013; Kuh, 2008).

To counteract these disadvantages, targeted institutional interventions are vital. Academic bridging programmes, mentorship schemes, financial aid guidance and inclusive community-building efforts have shown promise in enhancing student engagement and retention (Bui, 2002; Katrevich and Aruguete, 2017). Increasing access to tailored support services and addressing practical barriers such as financial aid accessibility can further improve outcomes (Wainwright and Watts, 2019). These initiatives not only address structural inequalities but also foster a more supportive academic environment.

The literature illustrates that first-generation students face multifaceted challenges – academic, financial, cultural and emotional – that intersect and influence their higher-education experience. While much of the evidence comes from US-based research (e.g. Stebleton and Soria, 2013), the core themes resonate globally. However, there remains a notable gap in UK-specific studies exploring how these barriers manifest within British higher-education contexts. Addressing this gap is crucial for developing more inclusive support systems tailored to the needs of first-generation students in the UK.

This study adopted a concurrent mixed-methods design within a case-study framework, underpinned by an interpretivist paradigm. The interpretivist lens enabled an in-depth understanding of the lived experiences of first-generation students, and recognised the socially constructed nature of their academic transitions and challenges. The case-study approach provided a contextualised focus on a specific institution – the University of Warwick – allowing for a holistic examination of student experiences within this setting.

A total of 34 participants were involved: 14 Warwick Scholars and 20 non-Scholars, primarily undergraduates. Of these, 25 identified as female and 9 as male, leading to a gender imbalance; hence, gender-specific analysis was not pursued to preserve the integrity of comparative outcomes.

Students enrolled in the Warwick Scholars Programme meet eligibility criteria that reflect socio-economic disadvantage, making them an appropriate group for this study’s focus on equity and access in higher education. The dual-method approach allowed the study to capture both broad trends and individual narratives across the two cohorts.

Structured one-on-one face-to-face interviews were conducted with first-generation students, including Warwick Scholars and non-Scholars from diverse gender, ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Interview questions explored academic transitions, family dynamics, financial pressures and future aspirations. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. A summary of interviewee demographics, including gender, Warwick Scholar status, education level and interview dates, is provided in Appendix A.

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data. Four key narratives were reviewed closely, and recurrent themes were identified and descriptive codes assigned (e.g., ‘Financial Impact’ or ‘Academic Preparedness and Confidence’). This coding process supported the generation of a thematic matrix which summarised key findings (see Appendix B).

Quantitative data was collected via an online Qualtrics survey distributed to eligible participants. It included multiple-choice demographic questions, Likert-scale items assessing academic and social experiences, and an optional open-ended question for further insights. Survey data was anonymised and analysed using Qualtrics’ descriptive statistics function.

Key demographic findings and patterns in the experiences of first-generation student are summarised in Appendices C and D.

Interview recordings were securely stored in a password-protected OneDrive folder, accessible only to the research team. After transcription and anonymisation, original recordings were deleted to protect participant confidentiality.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. They were briefed on the study’s aims and assured of anonymity and secure data handling. Ethical approval was granted by the University of Warwick’s Ethics Committee, confirming adherence to protocols involving human participants.

This section integrates quantitative survey data (see Appendix D: Comparative survey results – Warwick Scholars vs non-Scholars) with qualitative interview insights (see Appendix B: Summary of interview findings) to explore the lived experiences of first-generation students at the University of Warwick. While the survey highlights broad patterns, interviews provide rich, contextual depth that reveals how these trends play out in individual lives.

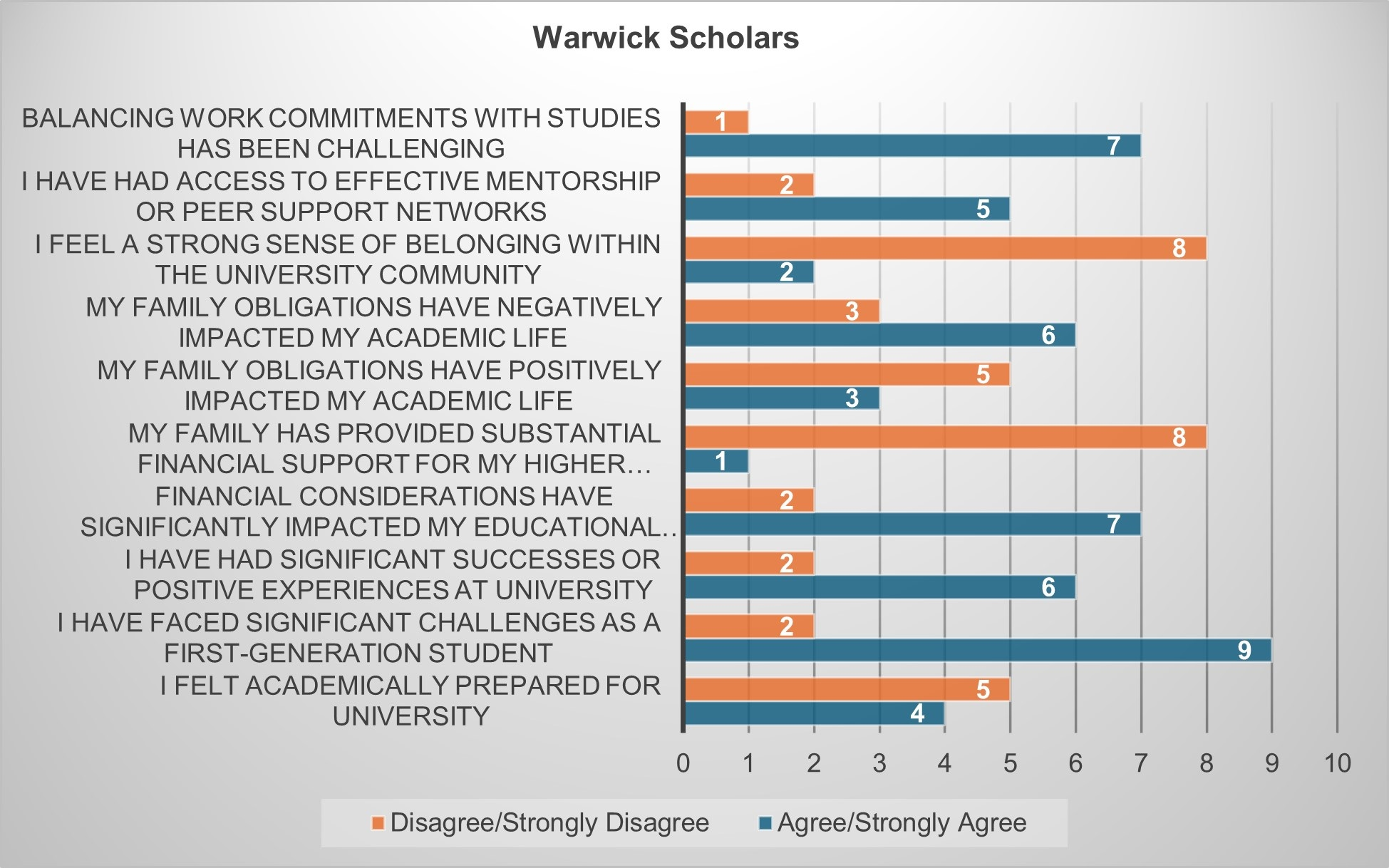

Figure 1: Clustered bar chart regarding experiences of first-generation Warwick Scholars

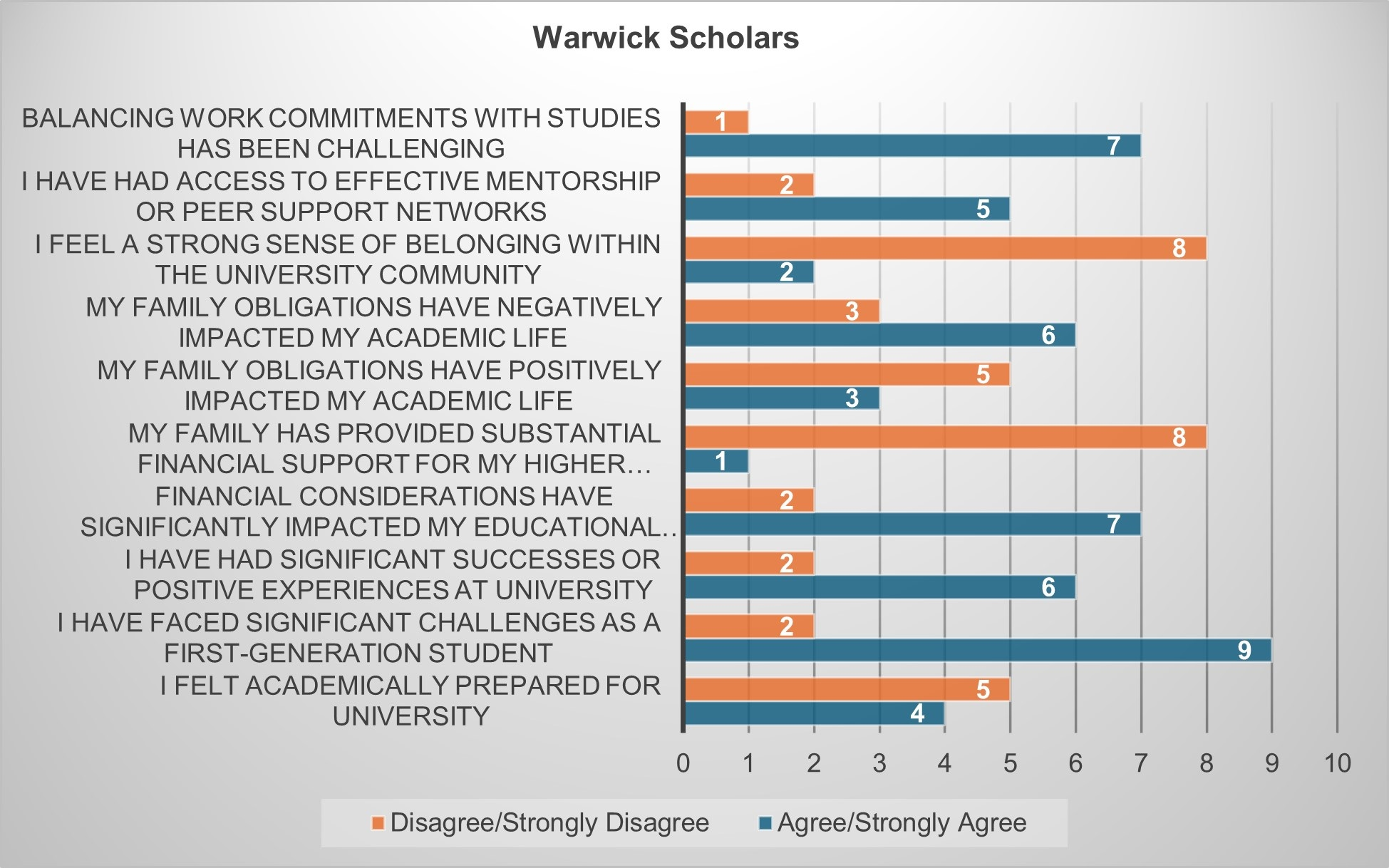

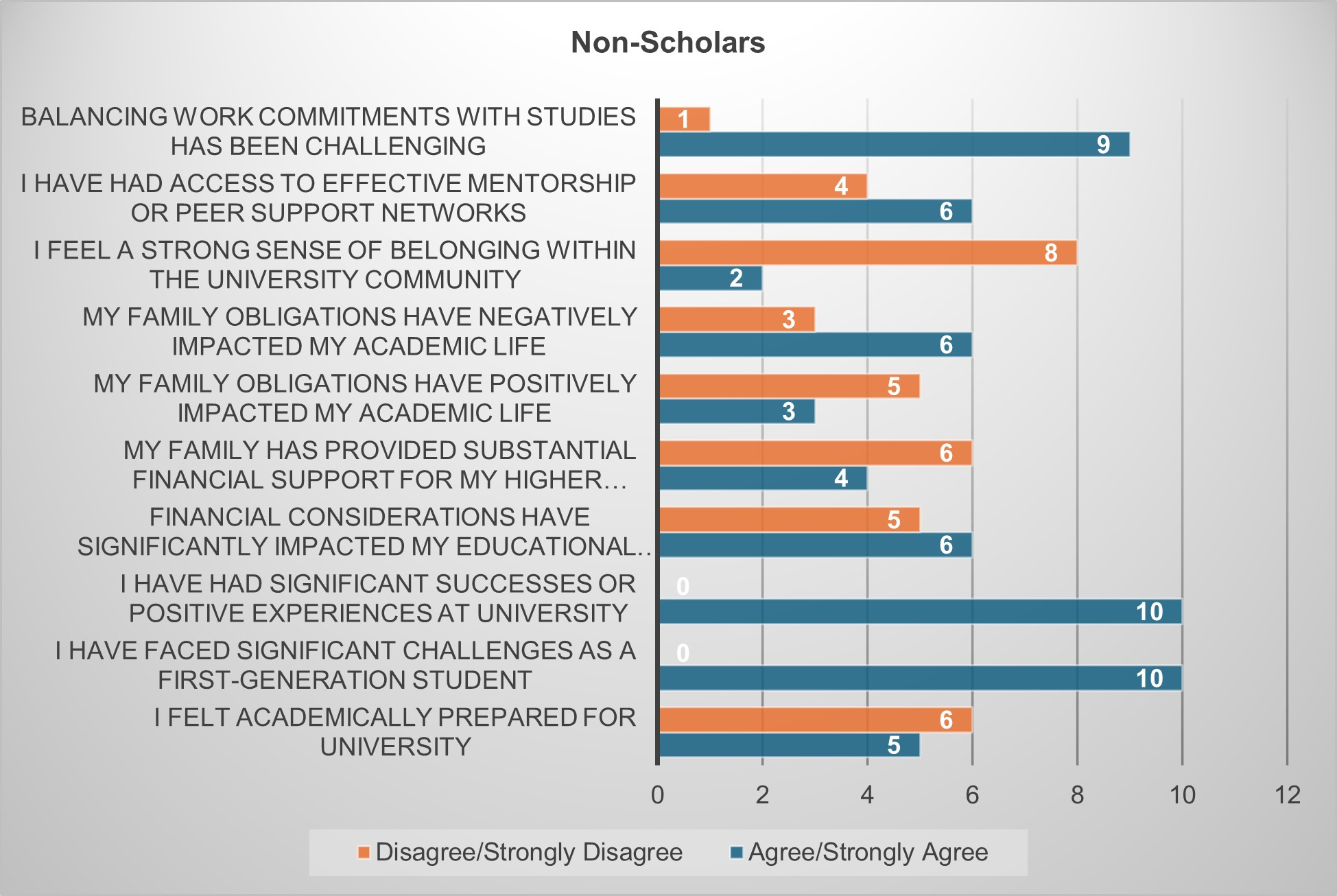

Figure 2: Clustered bar chart regarding experiences of first-generation non-scholars

Survey results (Appendix D) suggest comparable levels of perceived academic readiness between Warwick Scholars (36 per cent) and non-Scholars (42 per cent), indicating that scholarship status alone may not significantly influence preparedness. However, interview data (Appendix B, Table B1) uncovers important nuances. Some students described feeling underprepared due to limited support at school: ‘My A-level experiences were challenging due to inadequate preparation from school.’ Others credited their schools with fostering independent learning: My teachers encouraged me to explore topics on my own, which helped me adapt to university study.

These contrasting perspectives suggest that confidence in navigating academic demands at university stems more from pre-university experiences than post-entry support. While Warwick Scholars receive additional academic resources, these alone do not always translate into higher self-assurance.

Over 80 per cent of both Scholars and non-Scholars reported facing significant challenges, including financial pressures, navigating university systems and juggling competing responsibilities (Appendix D). These findings were echoed in the interviews (Appendix B, Table B2), where students spoke candidly about the strain of managing work and study: ‘I worked part-time, and it does interfere with my studies because it’s difficult to manage my time well’.

Financial constraints not only impacted daily life but also influenced course selection and long-term goals. For example, 64 per cent of Scholars and 50 per cent of non-Scholars reported that financial considerations shaped their academic decisions (Appendix D). Interviewees elaborated on how this impacted career planning: ‘I chose my course partly because it leads to stable, well-paying jobs.’ Budgeting and financial management emerged as consistent themes across both groups (Appendix B, Table B4): ‘I plan and cook my meals each week to make sure I have enough for essentials.’

Despite these challenges, students across both groups shared stories of resilience and accomplishment. Success was viewed not only through measurable outcomes – such as securing internships or scholarships – but also through personal growth and adaptation to university life (Appendix B, Table B3).

For instance, one student shared: ‘I used to be very introverted, but joining societies really helped me come out of my shell,’ illustrating how engagement in extracurricular activities supported personal development. Others highlighted more tangible milestones: ‘Securing a scholarship boosted my confidence and made me feel recognised.’ These varied definitions of success underline the importance of supporting both academic and personal development in holistic student experiences.

Family played a dual role – providing emotional motivation but limited practical guidance. All participants reported a lack of social capital in their families, which hindered their ability to navigate university life effectively (Appendix B, Table B5). While family obligations sometimes conflicted with academic priorities, family support remained a powerful motivator: ‘My parents had a big influence on me to pursue higher education as they have low-wage jobs and moved here to give me a better future.’

However, the absence of cultural capital often left students feeling unprepared for the social and institutional norms of university, reinforcing the need for external support mechanisms.

Experiences of social integration varied markedly. Only 18 per cent of Warwick Scholars reported a strong sense of belonging, compared to 50 per cent of non-Scholars (Appendix D), suggesting that institutional support systems may not fully meet the inclusion needs of all first-generation students.

Interview responses (Appendix B, Table B6) revealed how participation in extracurricular activities often promoted belonging: ‘Joining societies fostered a sense of community.’ Cultural background also played a role. For some, multicultural exposure aided social connection: ‘Coming from a multicultural background, I found it easy to relate to people from different cultures.’ Others, however, experienced a cultural disconnect that led to isolation: ‘Coming from a small, non-diverse town, I sometimes feel like I can’t fully fit in with certain groups because of cultural differences, which makes me feel a bit isolated.’ These findings underscore how both individual identity and institutional culture influence students’ sense of inclusion.

Access to academic support services varied across groups. Around 50 per cent of both Scholars and non-Scholars expressed satisfaction with available support, with Scholars slightly lower at 45% (Appendix D). However, Warwick Scholars were more likely to benefit from structured mentorship programmes, while non-scholars often relied on peer networks or personal tutors (Appendix B, Table B7). One student explained: ‘I didn’t use the mentorship programme much because I found enough support among my peers.’ Yet several students noted barriers to access, such as low awareness or stigma around seeking help: ‘I had a personal tutor, but it would have helped to have a peer mentor I could go to for advice.’ These insights suggest that increasing visibility and normalising the use of support resources could widen their reach, particularly for first-generation students unfamiliar with institutional systems.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics of support services access and perceived barriers (N = 12)

Group |

Sought support services (%) |

Needs met (Agree/ Strongly agree %) |

Barriers to access (%) |

Suggested improvements |

Warwick Scholars |

50 |

60 |

33 |

|

Non-Scholars |

17 |

50 |

50 |

|

Only 17 per cent of non-Scholars reported seeking formal support, compared to 50 per cent of Scholars, despite similar levels of satisfaction. This disparity indicates possible systemic barriers – such as lack of awareness, accessibility issues or stigma – that disproportionately affect non-Scholars. Even among Scholars, support was not universally sufficient.

To address these gaps, both groups recommended greater visibility, more proactive outreach and tailored resources. Scholars sought more structured guidance and skill-building opportunities, while non-Scholars emphasised the need for personal tutors to actively promote support services.

Figure 3: Warwick Scholars’ key suggestions in keywords

Figure 4: Non-Scholars’ key suggestions in keywords

Across both groups, students made targeted recommendations for improvement, particularly in mentorship, financial support and career guidance.

Warwick Scholars highlighted the need for:

Non-Scholars prioritised:

These suggestions, illustrated in Figures 3 and 4, reflect a shared desire for more inclusive, visible and personalised support systems. Both Scholars and non-Scholars value mentorship, financial clarity and accessible career pathways. Incorporating these insights into future policy and programme development is essential for fostering a supportive environment for all first-generation students at the University of Warwick.

Students from both groups expressed aspirations for meaningful careers and upward mobility. However, unequal access to internships, networks and development opportunities was a persistent concern. As one student observed: ‘More recognition for first-generation students and greater awareness of social mobility programmes would help’ (Appendix B, Table B9).

Students consistently called for structured, inclusive resources that target the distinct barriers they face. Career guidance, mentorship and community-building efforts were all highlighted as areas requiring focused investment. As one interviewee explained: ‘Having access to peer mentoring programmes, like the Buddy Scheme, gave me direction and reassurance – more initiatives like this would make a real difference.’

In discussing the triangulation of data from interviews, surveys and literature reviews regarding first-generation students, we observe consistent themes across different types of data collection methods. These findings collectively highlight the challenges and needs of this student demographic, providing a richer understanding than any single method could offer. The findings are discussed thematically and interpreted in relation to the existing literature.

1.1 Perceptions of academic preparedness

Participants’ reflections revealed varying levels of academic readiness. While many first-generation students reported difficulties adjusting to university-level expectations, their perceptions of preparedness were shaped not only by academic skills but also by their confidence and access to prior information. This aligns with Bui (2002) and Jehangir (2010, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013), who noted that many first-generation students enter university less academically prepared due to systemic disadvantages. The internalisation of these gaps often results in hesitation to seek academic support, echoing Pascarella et al. (2004) and Katrevich and Aruguete (2017). In line with Thomas (2006), the unfamiliarity with academic structures highlights the influence of limited cultural capital.

1.2 Specific transition challenges

The transition to university was frequently described as overwhelming, particularly in the first year. This finding supports Forsyth and Furlong (2003, cited in Thomas, 2006) and Stebleton and Soria (2013), who argue that institutional processes can feel alienating for first-generation students unfamiliar with academic norms. The intensity of independent study, time management demands and academic writing standards often created a steep learning curve, especially for those balancing other responsibilities.

1.3 Influence of financial considerations on educational choices

Financial pressures influenced many participants’ academic decisions, such as module selection, commuting versus living on campus, and part-time work. This supports Thomas (2006) and Bui (2002), who emphasised the significant role of financial barriers in shaping student engagement. Consistent with Jehangir (2010, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013), several students reported working alongside studies, which reduced their ability to participate fully in academic and extracurricular opportunities.

1.4 Impact of family financial dynamics on academic experiences

Family financial circumstances often placed implicit or explicit pressure on students, influencing their emotional well-being and time management. Some students felt obligated to support their families financially or prioritise cost-saving decisions. These experiences align with Wainwright and Watts (2019) and Jehangir (2010, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013), who found that first-generation students often feel responsible for family well-being. Living off campus due to cost constraints also reduced access to peer networks, a dynamic highlighted by Pascarella et al. (2004, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013).

1.5 Perceptions of belonging at Warwick University

Students’ sense of belonging varied, with many reporting initial isolation followed by increased integration through societies or academic groups. Interestingly, non-Scholar participants often reported greater ease in forming peer connections, suggesting that structured support schemes may not always equate to stronger social integration. This partially contradicts assumptions in the literature that institutional support programmes directly improve belonging (Kuh, 2008; Thomas, 2006). Instead, peer relationships and organic social encounters may play a more influential role.

1.6 Role of cultural background in university experiences

Cultural background played a significant role in shaping university experiences. Students from diverse or working-class families often described a sense of disconnection between home life and university culture. This cultural mismatch aligns with Rendón (1992, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013) and Oldfield (2007), who observed identity fragmentation among first-generation students. The literature suggests that this dissonance can lead to loneliness and affect persistence (Lippincott and German, 2007, cited in Stebleton and Soria, 2013), a trend reflected in the accounts of students who struggled to reconcile personal identity with institutional expectations.

2.1 Effectiveness of mentorship programmes

Experiences with formal mentorship schemes were mixed. While some Warwick Scholars appreciated structured guidance, others found the programmes too generalised or disconnected from their specific needs. This echoes Katrevich and Aruguete (2017), who found that while interventions can improve engagement, their effectiveness depends on personalisation and relevance. Peer support and informal networks emerged as particularly impactful, supporting Thomas (2006), who emphasised the role of community in student retention.

2.2 Perceptions of access to support services

Accessing university support services was seen as inconsistent. Some students were unaware of available resources or felt intimidated by the process. This mirrors findings by Wainwright and Watts (2019), who noted that institutional support is often under-utilised due to visibility and accessibility issues. Despite positive feedback from users of these services, the findings suggest a need for more proactive outreach and clearer signposting, particularly by personal tutors and academic departments.

This study explored the experiences of first-generation students at the University of Warwick, with a focus on both Warwick Scholars and non-Scholars. Drawing on both survey data and interviews, the research identified key challenges related to academic preparation, financial pressures, social and cultural integration, access to support services and career readiness. While Warwick Scholars generally reported greater engagement with structured services, both groups highlighted the need for more personalised and accessible support systems.

These findings reinforce existing literature, which highlights that first-generation students often experience educational disadvantage due to structural and cultural barriers (e.g. Bui, 2002; Jehangir, 2010). The results suggest that addressing these challenges requires a holistic, equity-focused approach that recognises the diversity and resilience of first-generation students. Universities must not only offer resources but also ensure these are visible, approachable and relevant to students’ lived experiences.

Based on the findings, the following recommendations are proposed to enhance support for first-generation students:

Expand access to counselling and practical workshops focused on academic skills, financial literacy and transitioning to university life.

Increase the availability of scholarships, bursaries and emergency funds. Ensure transparent and proactive communication about financial aid to ease student stress and widen access.

Develop peer and alumni mentorship schemes tailored to first-generation needs. Introduce targeted career development opportunities, including networking events and job preparation workshops.

Train academic departments and personal tutors to better signpost services using accessible, student-friendly language. Offer more tailored support aligned with individual circumstances.

Create more accessible placements, society involvement and inclusive events to help first-generation students build peer networks and a stronger sense of identity and belonging.

Future research should explore the intersectionality of students’ identities (e.g. ethnicity, socio-economic background and religion, as well as the effectiveness of these recommendations once implemented. Further investigation into the role of digital tools in supporting first-generation students may also prove valuable.

Importantly, first-generation students are not a homogenous group. Their experiences are shaped by a range of intersecting identities and personal circumstances. By acknowledging this diversity and building on the unique strengths that first-generation students bring to higher education – such as resilience, adaptability and fresh perspectives – universities can create a more inclusive and dynamic academic community.

By implementing these strategies, universities can better support first-generation students and cultivate a more inclusive, supportive and socially mobile academic community.

As a first-generation university student, this research journey has been deeply enriched by the continuous support and encouragement from many people and institutions. This achievement is not just an individual accomplishment but a reflection of the collective effort and belief in my potential.

My family has always seen education as a transformative force, and their role in my journey has been significant. They have instilled in me a sense of resilience and an appreciation for knowledge, encouraging me to take pride in my identity as a first-generation student. Their unwavering faith in my abilities has empowered me to engage in research projects where I can contribute novel insights, thereby helping to overcome obstacles and potentially making a significant difference in the broader field of study.

I extend my heartfelt thanks to the Social Mobility Student Research Hub at the University of Warwick for providing the platform and resources that have significantly enriched my paper. The hub’s dedication to bridging educational divides aligns perfectly with my own aspirations, reinforcing my commitment to using my research to positively impact society.

I am particularly grateful for the guidance of Aïcha Hadji-Sonni, whose mentorship and insightful feedback have been essential throughout this project. Her guidance not only helped me navigate report writing but also encouraged me to push the boundaries of my research.

I am also grateful to all participants who shared their stories and insights with me. Their contributions have been critical in shaping a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities faced by first-generation students. This paper would not have been possible without the convergence of personal support, institutional resources and academic guidance. I am thankful to each individual and institution that has contributed to this journey, and I dedicate this work to all those who, like me, are taking the opportunities of breaking barriers in higher education.

Figure 1: Clustered bar chart regarding experiences of first-generation Warwick Scholars

Figure 2: Clustered bar chart regarding experiences of first-generation non-scholars

Figure 3: Warwick Scholars’ key suggestions in keywords

Figure 4: Non-Scholars’ key suggestions in keywords

Table 1: Research questions

Table 2: Descriptive statistics of support services access and perceived barriers (N = 12)

Table A1: Interviewees

Table B1: Academic preparedness and confidence

Table B2: Challenges faced

Table B3: Success and achievements

Table B4: Financial impact

Table B5: Family and social dynamics

Table B6: Social and cultural integration

Table B7: Mentorship and academic support

Table B8: University support and resources

Table C1: Demographic breakdown of survey participants from the University of Warwick

Table D1: Comparative survey results: Warwick Scholars vs. non-Scholars

Table A1: Interviewees

Interviewee |

Gender |

Warwick Scholar? (YES/NO) |

Level of education |

Date of interview |

Student 1 |

F |

YES |

UG |

08/05/2024 |

Student 2 |

M |

NO |

UG |

17/05/2024 |

Student 3 |

F |

YES |

UG |

27/05/2024 |

Student 4 |

F |

NO |

UG |

10/06/2024 |

Table B1: Academic preparedness and confidence

|

Table B2: Challenges faced

|

Table B3: Success and achievements

|

Table B4: Financial impact

|

Table B5: Family and social dynamics

|

Table B6: Social and cultural integration

|

Table B7: Mentorship and academic support

|

Table B8: University support and resources

|

Table B9: Future aspiration and reflection

|

Table C1: Demographic breakdown of survey participants from the University of Warwick

Category |

Number of respondents |

Percentage (%) |

WP student |

||

Yes |

24 |

80% |

No |

6 |

20% |

Warwick Scholars Programme |

||

Yes |

12 |

50% (of WP respondents) |

No |

12 |

50% (of WP respondents) |

First-generation status |

||

First-Generation |

24 |

80% |

Not First-Generation |

6 |

20% |

Level of study |

||

Undergraduate |

26 |

87% |

Postgraduate |

4 |

13% |

Gender |

||

Male |

8 |

27% |

Female |

22 |

73% |

Note: The survey included 30 respondents in total. Of these, 24 were first-generation WP students. Among these, 12 participated in the Warwick Scholars Programme, and 12 did not, either because they did not meet all eligibility criteria, were unaware of the programme, or chose not to participate. The remaining six respondents were not classified as WP students. Percentages in the Warwick Scholars Programme category are therefore calculated based on WP respondents only (N=24).

Table D1: Comparative survey results: Warwick Scholars vs non-Scholars

|

Statement

|

Response |

Warwick Scholars (N = 12) |

Non-Scholars (N = 12) |

I felt academically prepared for university |

Agree/Strongly Agree |

36% |

42% |

Neither agree nor disagree |

19% |

8% |

|

|

Disagree/Strongly Disagree |

45% |

50% |

I have faced significant challenges as a first-generation student |

Agree/Strongly Agree |

82% |

83% |

Neither agree nor disagree |

0% |

17% |

|

Disagree/Strongly Disagree |

18% |

0% |

|

I have had significant successes or positive experiences at university |

Agree/Strongly Agree |

55% |

83% |

Neither agree nor disagree |

27% |

17% |

|

|

Disagree/Strongly Disagree |

18% |

0% |

Financial considerations have significantly impacted my educational choices |

Agree/Strongly Agree |

64% |

50% |

Neither agree nor disagree |

18% |

8% |

|

|

Disagree/Strongly Disagree |

18% |

42% |

My family has provided substantial financial support for my higher-education journey |

Agree/Strongly Agree |

9% |

33% |

Neither agree nor disagree |

18% |

17% |

|

|

Disagree/Strongly Disagree |

73% |

50% |

My family obligations have positively impacted my academic life |

Agree/Strongly Agree |

27% |

33% |

Neither agree nor disagree |

28% |

42% |

|

|

Disagree/Strongly Disagree |

45% |

25% |

My family obligations have negatively impacted my academic life |

Agree/Strongly Agree |

55% |

33% |

Neither agree nor disagree |

18% |

17% |

|

|

Disagree/Strongly Disagree |

27% |

50% |

I feel a strong sense of belonging within the university community |

Agree/Strongly Agree |

18% |

50% |

Neither agree nor disagree |

9% |

17% |

|

|

Disagree/Strongly Disagree |

73% |

33% |

I have had access to effective mentorship or peer support networks |

Agree/Strongly Agree |

45% |

50% |

Neither agree nor disagree |

37% |

17% |

|

|

Disagree/Strongly Disagree |

18% |

33% |

Balancing work commitments with studies has been challenging |

Agree/Strongly Agree |

64% |

75% |

Neither agree nor disagree |

27% |

17% |

|

|

Disagree/Strongly Disagree |

9% |

8% |

Note: Table D1 presents comparative survey results for WP students only (N=24), divided into Warwick Scholars (N=12) and non-Scholars (N=12). Percentages for each response category (Agree/Strongly Agree, Neither agree nor disagree, Disagree/Strongly Disagree) are calculated within each subgroup and sum to 100% for that subgroup. The six non-WP respondents are excluded from this comparison. Respondents indicated their level of agreement with the statements above, which served as the survey questions.

Adamecz-Völgyi, A., M. Henderson and N. Shure (2020), ‘Is “first in family” a good indicator for widening university participation?’, Economics of Education Review, 78, 102038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2020.102038

Bui, K. V. T. (2002), ‘First-generation college students at a four-year university: Background characteristics, reasons for pursuing higher education, and first-year experiences’, College Student Journal, 36, 3–11

Engle, J. and V. Tinto (2008), Moving Beyond Access: College for low- income, first-generation students. Washington, DC: The Pell Institute. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED504448. accessed 11 May 2011

Forsyth, A. and A. Furlong (2003), Socio-Economic Disadvantage and Access to Higher Education, Bristol: Policy Press

Henderson, M., N. Shure and A. Adamecz-Völgyi (2020), ‘Moving on up: ‘first in family’ university graduates in England’, Oxford Review of Education, 46 (6), 734–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1784714

Jehangir, R. R. (2010), Higher Education and First-Generation Students: Cultivating Community, Voice, and Place for the New Majority, New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan

Katrevich, A. V. and M. S. Aruguete (2017), ‘Recognizing challenges and predicting success in first-generation university students’, Journal of STEM Education: Innovations and Research, [online] 18 (2). https://www.jstem.org/jstem/index.php/JSTEM/article/view/2233/1856, accessed 11 May 2011

Kuh, G. D. (2008), High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter, Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities

Lippincott, J. A. and N. German (2007). ‘From Blue Collar to Ivory Tower: Counseling First-Generation, Working-Class Students’, in J. A. Lippincott and R. B. Lippincott (eds.), Special Populations in College Counseling: A Handbook for Mental Health Professionals, pp. 89–98, Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association

London, H. B. (1989), ‘Breaking away: A study of first-generation college students and their families’, American Journal of Education, 97, 144-70

Oldfield, K. (2007). ‘Humble and hopeful: Welcoming first-generation poor and working-class students to college’, About Campus, 11 (6), 2–12

Pascarella, E. T., C. T. Pierson, G. C. Wolniak and P. T. Terenzini (2004), ‘First-generation college students’, The Journal of Higher Education, 75 (3), 249–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2004.11772256

Rendón, L. I. (1992), ‘From the Barrio to the Academy: Revelations of a Mexican American “Scholarship” Girl’, in L. S. Zwerling and H. B. London (eds.), First-Generation Students: Confronting The Cultural Issues, (New Directions for Community Colleges Series, No. 80), pp. 55–64. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Stebleton, M. and Soria, K. (2013), ‘Breaking down barriers: Academic obstacles of first-generation students at research universities’, Conservancy.umn.edu. [online] https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/150031, accessed 11 May 2011

Thomas, L. and J. Quinn (2006), EBOOK: First Generation Entry into Higher Education. [online] Google Books. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill Education. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=LE5EBgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Thomas+2006+first+gen+student&ots=rW8PoO_laY&sig=ryxPe7DznKO5BTzLR18cE1dyOe8&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Thomas%202006%20first%20gen%20student&f=false, accessed 7 May 2024

University of Warwick (2025), ‘Warwick Scholars’, [online] Warwick.ac.uk. Available at: https://warwick.ac.uk/study/outreach/whatweoffer/warwickscholars, accessed 1 Aug. 2025

Wainwright, E. and M. Watts (2019), ‘Social mobility in the slipstream: First-generation students’ narratives of university participation and family’, Educational Review, 73 (1), 111–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2019.1566209

First-generation students: Students whose parents or guardians have not completed a university-level degree.

Warwick Scholars Programme: A programme at Warwick University providing support, skill development, and opportunities for students from underrepresented or disadvantage backgrounds.

UK Russell Group university: A group of 24 leading UK universities in the UK known for high research output, academic excellence, and selective admissions.

Widening Participation: Policies and initiatives aimed at increasing access to higher education for students from underrepresented or disadvantaged backgrounds

Mixed-methods approach: Research that combines quantitative data (e.g., surveys, statistics) and qualitative data (e.g., interviews) to gain a comprehensive understanding of a topic.

Cultural capital: The knowledge, skills, behaviour, and social assets that give individuals advantages in education and society, often influenced by family background and upbringing.

Social capital: The networks, relationships, and social connections that provide individuals with support, resources, and opportunities, often influencing education and career outcomes.

Systemic disadvantages: Structural inequalities or barriers within society and institutions that limit opportunities or outcomes for certain groups, often based on socioeconomic background, race, gender, or other factors.

To cite this paper please use the following details: He, J. (2025), 'Breaking Barriers: A Comprehensive Study on the Pathways and Challenges Faced by First-Generation Students in Higher Education', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 18, Issue 2, https://reinventionjournal.org/index.php/reinvention/article/view/1821. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities, please let us know by emailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.

https://doi.org/10.31273/reinvention.v18i2.1821, ISSN 1755-7429, © 2025, contact reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk. Published by the Institute for Advanced Teaching and Learning, University of Warwick. This is an open access article under the CC-BY licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)