Eve and Other Poems

Lily Thwaites, University of Warwick

Abstract

To further explore the patriarchal adaptations made to female biblical characters, I have experimented in creating poetry from the female perspective of Eve in the creation story (Genesis). Like Mary Magdalene, Eve has been aligned with original sin and it is this story that was frequently used to justify the treatment of women by the church. Instead of focusing specifically on sin, I wanted to create a poem that explored what it may have been like to exist before the concept of ‘the past’ and ‘time’, as well as suggest what it may have been like for Eve to experience the world after she had eaten from the Tree of Knowledge. If our understanding of good and bad is a result of their contrast, then surely, without ever having experienced evil before she bit the apple, how could Eve (and Adam) ever have truly appreciated or understood ‘paradise’ or the parameters of the Garden of Eden? There are more interesting philosophical discussions to be had about the creation story aside from simply that women are the cause of original sin. ‘Mother Nature’ encompasses both the labours of women and the present-day ecological issues that connect with the original creation story. Likewise, on the theme of feminist mythological retellings, the tale Pygmalion inspired the poem ‘not my bed’, which is a modern-day take on the blurred lines of consent, focusing solely on the female experience, in the wake of the #MeToo Movement and the Warwick Rape Chat Scandal.

Eve

and so, she looks around and sees this:

grass that is always green, flowers

that are always open,

their delicate centres exposed towards the sky,

petals reaching upwards and outwards.

she stretches her arms upwards and outwards

looks beyond her finger tips, sees a line of trees,

and thinks

- has that always been there?

she looks up. the sky is clear, the sun is strong

but not too strong, she sees the flowers again

and thinks

what does it mean to bloom, if the flowers

always look like this?

something comes over her, an urge, she

picks one in between her fingers and crushes it

the stoma bleeds into her fist

she wipes it on her leg

the deep red lingers on her thigh

she tries to wipe it off again, sees her skin flush and

mark,

scrubs and scrubs, pinpricks of blood rise to the surface

she thinks

it burns

then steps into the stream,

- why? -

feels the cool against her skin

and thinks

the water’s never felt as sweet as it does now

and then she halts.

she inhales.

she feels the air inside her lungs

and holds it there for a while until

it burns

then blows it out and lets it ripple across her lips

breathes in again, quickly,

the air has never felt as sweet as it does now

feels her heart thudding in her chest

and stops and thinks some more.

lifting her right fingertips to the inside of her arm

she hesitates and brings her nail against the flesh

and presses - cautiously at first, then hard

it burns

and so, she pulls her hand away and watches as

red trickles down her arm

then dips it in the water, sees the colour swirl

and disappear away from her.

she laughs

and stretches her arms upwards and outwards

towards the sky.

here’s something new:

a dark cloud looming in the distance

she watches it as it grows closer

looks back above her hands and thinks

the sky has never looked as blue as it does now

the world appears in front of her.

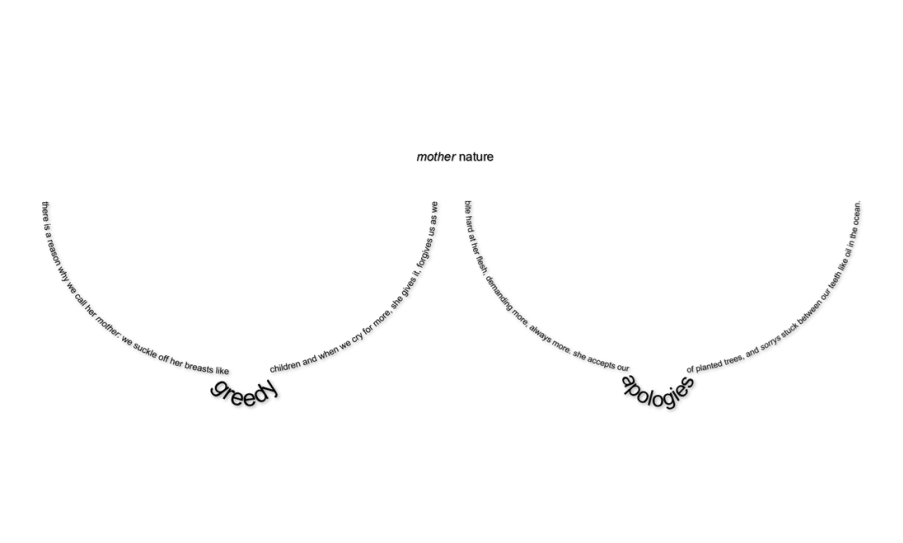

mother nature

Transcript

mother nature

there is a reason why we call her mother: we suckle off her breasts like greedy children and when we cry for more, she gives it, forgives us as we bite hard at her flesh, demanding more, always more, she accepts our apologies of planted trees, and sorrys stuck between our teeth like oil in the ocean.

not my bed

the woman lies

here on a bed frame

not on the side

of a street but inside a house. she is not far from

her home, her bed

but here she is asleep or awake and waits just

there with the stiff air caught

in her throat.

although some time has passed now

she waits to hear the

breath next

to her loud and deep with sleep and the odd car

outside the walls.

head full of fog she tries to move one leg out of

the sheet onto the cold floor, sees a bruise

on her hip

bare thigh caught in the breeze

she trips over her top and

blinks in the dark, shakes as her mind thinks of

his lips on her cheek

her neck. at the edge of the room her skirt has been

left, she thinks “that will leave a crease

in the morning” and

looks at the watch still on her wrist

but it is the next day

so it will be creased and it will be thrown out.

still she goes to put it

on

it weighs down on her limbs. Clothes don’t

feel the same, not now, and she

can’t find her pants

leaves them behind and creeps down the

stairs

can’t find her keys or phone

and so she goes back up the stairs, which door was it

she came from?

shuts her eyes and picks the one on the left and

finds her bag, picks it up goes back down the stairs leaves

out onto the drive walks down the road

to see what she can see and sees

a street sign that says almost home

in more or less words and also says my bed, my house

and safe

goes down five streets along six houses, puts her key into

the

lock, falls back against the door, at last she cries.

It is curiosity that drives me there.

Excitement is humming through the city, the fervour of it hangs thick and heavy in the air. Frenzied chatter lines the marketplace and hurries down the side streets, questions are shouted through windows to neighbours, answers given at shop stalls as they buy their daily loaves. But underneath there’s something else, a subtle stench of fear; it lingers behind each spoken word and answered question, behind each set of eyes, a hesitation.

It is curiosity that drives me there,

later, when the crowds have dispersed and only a few are left lounging across the earth, talking to friends and neighbours, the spectacle in front of them forgotten as they break their bread and eat, their children running and playing games across the open land outside the city walls. Only when they glance up to check where their children have run off to do they catch sight of the wooden crosses in front of them and pause, mouth full of bread, and swallow heavily, it catching in their throat. But then, someone asks another question – how old is your son now? Isn’t the air warm tonight? – and the spectacle is forgotten once again.

It is curiosity that drives me there

to look into his eyes and know for certain who I am looking at: a liar or a king. Instead, I see a man. A man whose face is streaked with tears, blood dripping down his brow, whose hands and feet are dirtied, flesh torn, limp limbs nailed in place, out of place. I see a man whose eyes are not quite shut, head hanging as he mouths words lost to the warm air and cloudless sky.

And when I turn away, I pray death comes for him soon.

Generational dementia

They say they think it is dementia, but

there’s nothing showing on the tests they do.

The scans look normal. The blood tests they

take just in case run clear as water.

Each time we take the trip to The Royal Free,

and they ask you questions, play memory games

with you, you say I am not a child

and repeat

cat, house, watch,

simply, quickly, clearly,

placing numbers around clockfaces;

I know how to tell the time

(but forget your daughter for a moment

when you wake).

Later in the day

you recall how, when I was seven,

I went to the hospital with a splinter in my foot

That had grown into the sole,

Swollen like a sixth toe.

You remember being told that

the surgeons had put me to sleep, sliced it out

And stitched me up.

But you do not remember how

I had been running around the

busy streets for days, barefoot because

you would not buy me shoes –

complained I wore them out too quickly:

a girl should not run about as you do,

her shoes should not last less than a year,

or feet grow big like a man.

You do not remember that I woke up

in hospital,

with a slice of my foot gone,

alone,

because you had gone for champagne and scones

at the Peninsula.

And now, I sit in the waiting room

as they take you for another scan.