Minaa Mujib, University of Exeter

This paper aims to illustrate the tension between public health and civil liberties through the case study of the UK government’s emergency response to the Covid-19 pandemic. In the area of public health, this tension is predominantly approached by reference to two theories: liberalism and communitarianism. This paper studies these positions and how they are manifested in evidence-based policymaking by combining a study of public health policy with a study of public health ethics. The studies help demonstrate the UK government’s framing of health policy relating to Covid-19 in terms of liberalism and communitarianism. The paper concludes that in the initial UK government response to Covid-19, the government discourse evoked communitarian values and framed its policies as being evidence-led and as prioritising public health. However, the policy measures themselves manifested liberal values: they had the underlying concern of not infringing excessively on civil liberties, and individuals were given autonomy of decision making within the measures that were taken. The article concluded that emergency times require a communitarian response based on preventative action. This article is the first to combine public health policy with public health ethics to demonstrate how values form a key part of decision making.

Keywords: Health policies and civil liberty, liberal values and Covid-19, liberal and communitarian conflict, public health ethics and evidence-based policy, public health policy and public health ethics during Covid-19 pandemic

Civil liberty is a value that is at the heart of Western societies, manifesting within their democratic structures (Schmitter and Karl, 1991). However, in emergencies, governments may need to temporarily restrict this liberty (Orzechowski et al., 2021). Due to the threat that the Covid-19 pandemic posed to civil liberties, many suggested that ‘democracies were slower to react to the pandemic’ (Cheibub, Hong and Przeworski, 2020: 20), and that countries such as the UK, Sweden and the US applied a libertarian response to the pandemic (Marginson, 2020; Lawrence, 2020; Fahlquist, 2020). Thus, the virus created a moral dilemma for liberal democracies: they sought to find the right balance between maintaining civil liberties and protecting public health.

It is often argued that, for Western democracies, public policy is evidence-led (Cairney, 2021; Williams et al., 2020). While the UK government justified its decisions as being based on scientific evidence, this has been disputed (Reynolds, 2020). In the absence of definitive evidence at the early stages of the pandemic, scientific advice often varied, which resulted in the selective picking of evidence (Zaki and Wayenberg, 2020). Similarly, Lawrence contends that ‘the diverse interpretations and responses of governments and public administrations confirm that “evidence-based policy” is a theoretical concept that is often not applied’ (Lawrence, 2020: 587) Thus, governments’ use of scientific evidence is analysed in this research article.

This paper aims to uncover the role of values in political decision making. This is explored through conducting a qualitative study of the UK government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic, considering the civil liberty–public health tension. Within public health, this tension is predominantly approached by two theories: liberalism and communitarianism (Brody, 1993; Childress and Bernheim, 2003; Parmet, 2003). This paper considers these positions and how they manifested in evidence-based policymaking. The paper combines the study of public health policy (PHP) and public health ethics (PHE) to explain the UK government’s framing of health policy relating to Covid-19.

An interpretive policy analysis (IPA) was conducted to understand where the UK government lay on the liberalism–communitarianism spectrum and how this impacted resultant policies. Therefore, the research ontology is social constructionism, ‘whereby the social reality is not singular or objective but is rather shaped by human experiences and social contexts’ (Bhattacherjee, 2012: 103). The epistemological stance is interpretive to see how this democratic ontology was challenged by emergency measures taken during Covid-19. In this sense, the research paradigm is interpretive.

Thus, the paper focuses on the UK’s public health discourse during the initial phase of the pandemic: from the identification of the virus until the imposition of the first lockdown at the end of March 2020. It demonstrates how values can play a fundamental role in decision making and argues that emergencies require acting preventatively, even if it infringes on fundamental freedoms.

Civil liberties relate to citizens’ rights that are protected by a country’s constitution, ‘such as freedom of movement, freedom of enterprise, and freedom of assembly’ (Belin and Maio, 2020). Governments cannot interfere with these rights and have an obligation to protect them by law (Hickman et al., 2020). This paper focuses on the civil liberties of freedom of movement and choice, given Covid-19’s impact on fundamental freedoms through government-implemented non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs).

Public health, however, is concerned with the health of the entire population, as opposed to just individuals (Childress and Faden, 2002). Civil liberties and public health goals can often conflict – for example, regarding the ‘right’ to smoke. Thus, many PHE frameworks seek to define an approach for responding to conflicts that arise between civil liberties and efforts to promote or protect public health. This tends to focus on government approaches, because of governments’ unique ability to construct a collective response (Cetron and Landwirth, 2005). Therefore, governments have specific responsibilities and powers in relation to public health concerns.

The PHE debate on the relationship between civil liberties and healthcare will broadly be divided into two approaches: liberal and communitarian.

Liberalism is based on the value of individual liberty and considers it a fundamental good, and thus the theory holds that strong justification is required when liberties are curbed by paternalistic government interventions (Faden, Bernstein and Shebaya, 2020). Communitarianism subordinates an individual’s liberty to the welfare of the community and values paternalistic actions insofar as it promotes that welfare (Forster, 1982). These perspectives can be seen as the two opposite ends of a spectrum, but they are not mutually exclusive.

PHE often assumes a liberal approach. This is based on the argument that liberal values are fundamental to democracy and need to be prioritised (Myers, 2016). Other scholars add that there needs to be respect for individual autonomy. However, most liberals consider it justified to restrict liberties in accordance with John Stuart Mill’s harm principle (Powers et al., 2012): that is, liberties should be curbed if their exercise inflicts harm on others (Mill, 1859). Nonetheless, according to a liberal perspective, such restrictions should take the form of soft paternalistic measures, like nudging, with the primary responsibility for health resting on individual action (Baggott, 2010). Accordingly, Gostin and Hodge (2020) define a framework for evaluating public health responses based on such considerations, including the risk posed by individuals, the efficacy of the interventions, the least-restrictive means that can be applied, the proportionality of coercion and an assessment of the evidence used to arrive at the means.

In the literature, communitarianism is often presented as a counter to liberalism and does not have a distinct framework of its own. However, communitarian values help us to understand the approach to public health according to communitarianism. Forster argues that a communitarian response ‘encourage[s] people to recognise their mutual dependencies, concern for the well-being of the community’ (Forster, 1982: 161). For Petrini, ‘in the communitarian perspective, the health of the public is one of those shared values: reducing disease, saving lives, and promoting good health are shared values’ (Petrini, 2010: 193). Therefore, a communitarian view evokes values that prioritise the community’s common good. It assigns responsibility to individuals to act in a manner that benefits the community.

A critical difference between the liberal view and the communitarian view is that liberalism values the conception of the good of each individual, whereas communitarianism values the good of the whole community higher than individual rights (Turoldo, 2009). Hence, a communitarian view takes a ‘paternalistic’ approach, developing a view of ‘community’ and encouraging responsibility towards the community. Paternalism here means that the primary responsibility for protecting public health lies with the government, while the community is obliged to follow whatever the government ordains, given the (espoused) benefit to the common good of the community (public health) (Baggott, 2010). Thus, in a communitarian view of public health, the primary responsibility lies with the government to create a collectivist response, even if that requires paternalism.

Overall, there is consensus that both the liberal and communitarian viewpoints allow limiting civil liberties in public policy responses to emergencies. However, the difference lies in the extent of that action, and justifying it.

To examine policymaking, a third approach to public health – beyond the ethical dilemmas – can be found in the PHP literature. There is debate within PHP regarding its approach to public health. While some argue that PHP is purely evidence-based (Brownson et al., 2009; MacIntyre, 2011), others argue that it is in fact political- and value-laden (Fafard, 2015; Fischer, 2003; Leeuw et al., 2014). Thus, a predominant debate is whether the policy process is evidence-led.

An evidence-based policy approach assumes a linear policymaking process in which experts give evidence, and the government makes policy based on what they deem to be the best outcome (Bambra, 2009). This approach aims to bridge the ‘gap’ between the political and the scientific (Cairney and Oliver, 2017; Smith, 2013).

However, many argue for the need to further develop research methods in PHP analysis because despite the presence of evidence-led policy, ‘[often] public health decisions […] do not reflect the best available scientific evidence’ (Fafard, 2015: 1129). There are two explanations for this: either the science itself is disputed, or politics plays a significant role (Baggott, 2015; Sisnowski and Street, 2008). Both explanations highlight the complexity of decision making, given that ‘public health policy decisions often involve normative and ethical decisions which evidence alone cannot answer’ (Smith, 2013: 69). Furthermore, often evidence only comes about after a policy has been implemented. Hence, PHP analysis should incorporate political science approaches to explain deviations from evidence and the policy process (Oliver, 2006).

This calls into question what other tools should be employed in efforts to understand policy. As Chadwick debates, ‘should the [method] attempt to discern the “core elements” of an “ideology” (understood as a “system of ideas”), or understand it as a tension between two extremes, such as libertarianism and collectivism?’ (Chadwick, 2000: 289). Bacchi contends that how a policy frames a problem reveals the values that are prioritised (Bacchi, 1999). As this paper is viewing which values are manifested within policy, Chadwick’s method of exploring a tension seems to fit best. Therefore, the use of scientific evidence in policymaking can be contrasted with the discourse involved in the decision-making process in order to understand how the evidence is used and how issues are framed.

As PHP is a new field of research, no framework has yet been developed to assess the values that are prioritised in policymaking. To the author’s knowledge, this is one of the first papers to combine PHP and PHE to assess the role of values in policymaking.

This paper applies the IPA framework to explore the theoretical underpinnings of the UK government’s approach to Covid-19. The study focuses on the UK as I experienced that country’s response and formed a good understanding of what avenues the government was using and what information was available to the public.

Considering the research questions, IPA is the most appropriate analytical method for this paper as it ‘often focus[es] on “puzzles” or “tensions” of two related sorts’ (Yanow, 2000), which is what this paper aims to do: analyse the tension between civil liberty and public health. Understanding the discourse around a particular issue helps recognise the ideology that is being applied (Chadwick, 2000).

Yanow’s framework for analysis entails the following steps:

This framework focuses on the expression of social meanings in terms of ideal values, beliefs and feelings. In this way, the events and actions, in relation to subjective meaning and the motives of the actors, can be understood (Fischer, 2003).

The artefact I studied was the language used by government officials in their public statements and policy documents, as language is value-laden. This consisted of statements, documents of government action plans and policy documents from the identification of the virus until the lockdown in March 2020. The community of meaning, or interpretive community, refers to ‘the groups for whom the artefacts have meaning’ (Yanow, 2000: 27). The interpretive community for the national policies was the public. Therefore, this article interpreted the policy artefacts from the public perspective.

The research’s prime focus was on the government’s approach to the pandemic; therefore, policy narratives were used as the main framework to identify the patterns and relationships to locate the issues in the reform agenda. Policy narrative framework until 2015 was taken as a quantitative and structured method of analysis (Gray and Jones, 2016). However, it is now viewed as a qualitative method to understand the underlying meanings hidden in the context. For this research, the main function was to understand the difference between what was said, how it was said and what was not said.

The policy themes were uncovered from the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) policy recommendations that the government implemented. Initially, the data was loosely categorised into as many clusters as was necessary, and only when this was achieved were the clusters with similar ideas grouped together. The clusters were formed based on the use of repeated words, which brought three broad themes into focus: nudging, national recommendations and lockdown (see Appendix 1). The process of identifying the broad themes was aligned with Yanow’s interpretive analysis where ‘the “data” of interpretive analysis are the words, symbolic objects and acts of policy-relevant actors along with policy texts, plus the meanings these artefacts have for them’ (Yanow, 2000: 27). For analysis, a spreadsheet was prepared and the broad themes were put at the top.

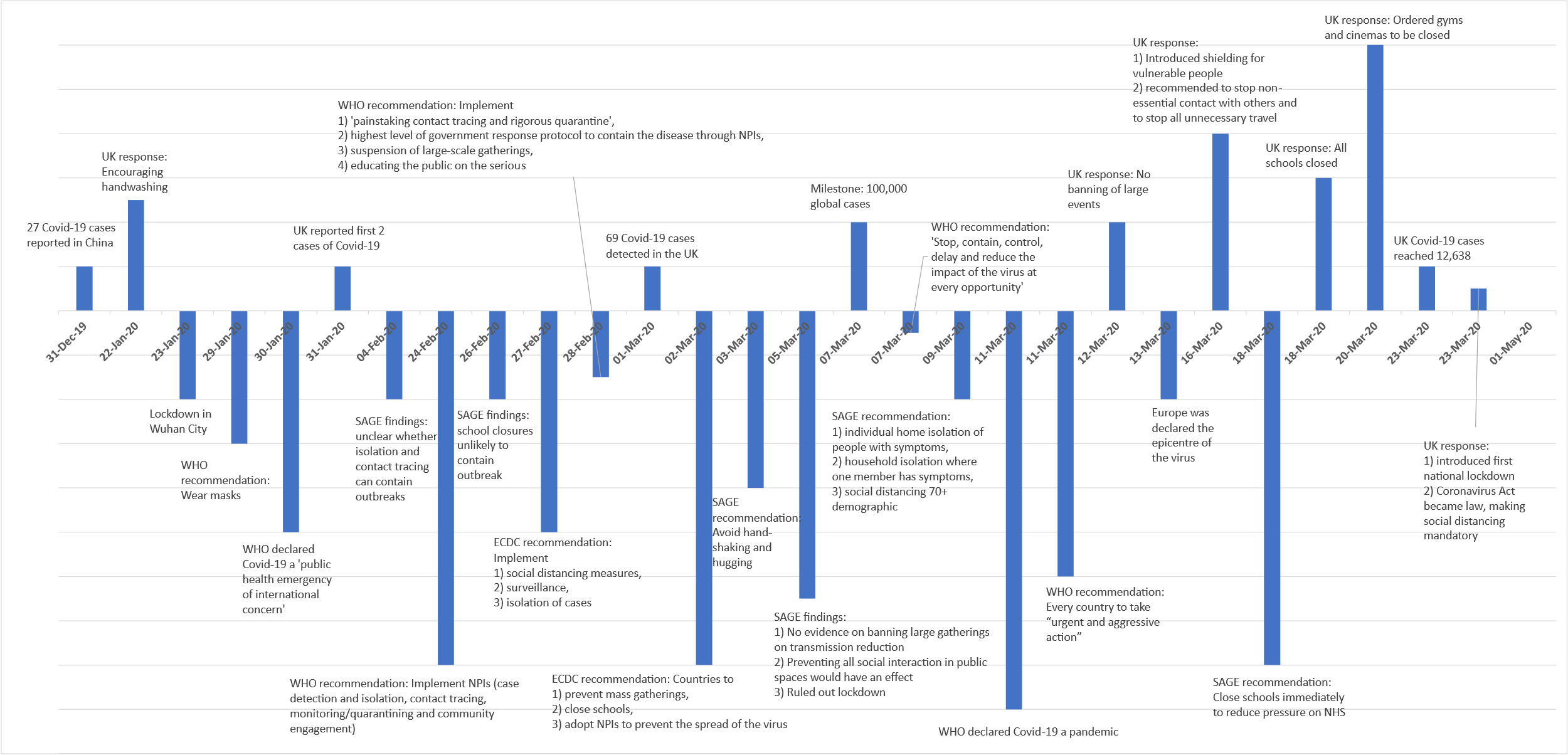

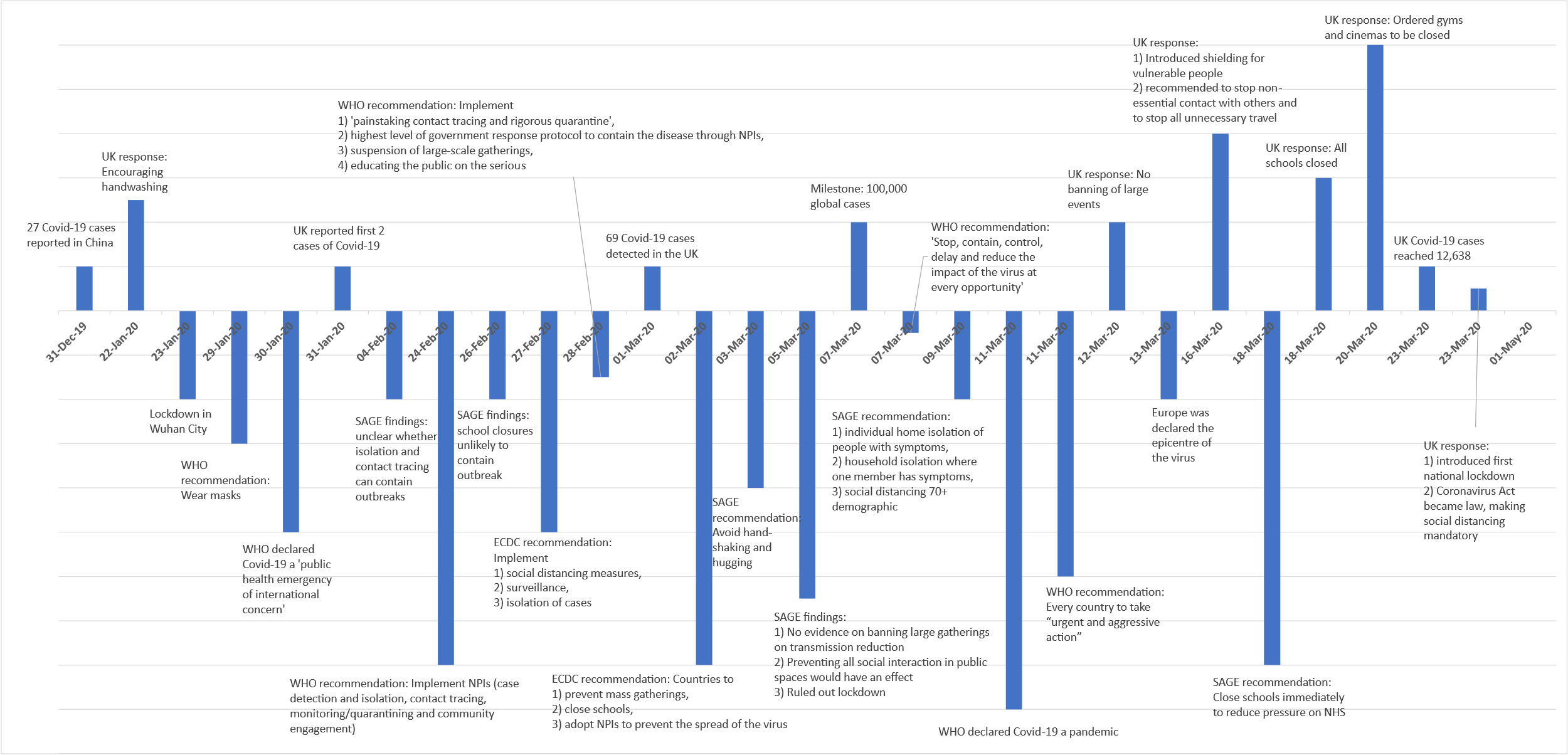

IPA requires identifying points of conflict to reflect interpretations, which I did by drawing a timeline of the available evidence and government policy to interpret the policy discourse in terms of any conflict with scientific evidence. To do this, the analysis looked at including the scientific evidence from three major scientific bodies to see if the government followed the larger recommendations. This included the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The first was the consulted organisation by the government, the second was the global recommendations and the third was a respected body of countries with similar values to the UK. The scientific evidence was identified from the research publications of these organisations and, in the case of SAGE, from the minutes of the group’s meetings as well.

This research added to the existing literature by focusing on government discourse to enable an understanding use of values through language justifying the decision making by comparing the evidence available at the time.

The paper conducts data triangulation for validity by including news sources in the analysis to uncover different interpretations of the government’s policies. Four primary UK news sources (the BBC, The Guardian, the Independent and the Daily Mail) are used to find further statements and analysis of the government’s Covid-19 response to identify other interpretations of the response. These news sources each lay on different ends of the political spectrum; this eliminates the bias of looking at one perspective.

However, the article only focuses on behavioural and social interventions. Other measures such as policing, travel policies and vaccine passports are not within the timeline or scope of research under behavioural interventions. As the paper focuses on the initial emergency response, this research is not indicative of the entire UK response.

China first informed the WHO of a novel coronavirus on 31 December 2019. The UK government’s first statement on the virus came on 22 January 2020, reporting that they were monitoring the disease and advised against travel to China. On 30 January, the WHO declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. On 11 March, the WHO declared Covid-19 a pandemic, three months after China had reported its initial cases (WHO, 2020a). On 31 January, two cases were identified in the UK; by 1 March, the cumulative cases identified numbered 69, and by 23 March (when a lockdown was announced), this had gone up to 12,638 cases (PHE, 2021). This is summarised in Figure 1 below.

Considering these events, the policy shifts are broken down into categories of ‘nudging behaviour’, ‘forming national recommendations’ and ‘implementing a lockdown’.

From 31 January to 15 March 2020, the UK government’s policy was to nudge people’s behaviour towards adopting hygiene practices like regular handwashing. Thus, while other countries (like Italy, Spain and New Zealand) imposed lockdowns during this time, the UK’s policy to control the rising number of cases was non-intrusive.

Although the government seemingly prioritised public health and nudged behaviour, this action was limited compared to that taken by other countries. On 9 and 12 March, Johnson stated: ‘I’m afraid it bears repeating that the best thing we can all do is wash our hands for 20 seconds with soap and water’ (PMO, 2020b; PMO, 2020c). This implicit assumption about the limited efficacy of other actions undermined preventative measures.

Even when the government emphasised a community-centred outlook, much of this remained advisory in nature. On 9 March, for example, Johnson stated: ‘we continue to look out for one another, to pull together in a united and national effort’, and he emphasised the need to ‘commit wholeheartedly to a full national effort’ (PMO, 2020b). However, Johnson stressed that ‘the vast majority of the people […] should be going about our business as usual’ (PMO, 2020a).

This inaction was in the face of varying (and limited) scientific evidence. Both the WHO and ECDC recommended that governments implement NPIs, such as preventing mass gatherings. On 28 February, the WHO released a mission report regarding all scientific information gathered on Covid-19 from China and the recommended country responses (WHO, 2020b). For countries with Covid-19 cases, the WHO’s recommendations included ‘painstaking contact tracing and rigorous quarantine’, the suspension of large-scale gatherings, and educating the public on the disease. The ECDC published a report on 27 February recommending the implementation of social-distancing measures, surveillance and isolation of cases (ECDC, 2020a). On 2 March, the ECDC recommended NPIs to prevent the spread of the virus, including preventing mass gatherings and school closures for countries with clusters of cases (ECDC, 2020b). This became the recommendation for all European Union countries by 12 March (ECDC, 2020c). Meanwhile, on 11 March, the WHO categorised Covid-19 as a pandemic, and the organisation’s Director-General called on every country to take ‘urgent and aggressive action’ to stop the spread of the virus (WHO, 2020a).

By contrast, SAGE meeting minutes on 5 March convey that ‘there is no evidence to suggest that banning large gatherings would reduce transmission. Preventing all social interaction in public spaces, including restaurants and bars, would have an effect, but would be very difficult to implement’ (SAGE, 2020b). This was contradictory: SAGE stated that there was no evidence about such matters, but it also suggested that preventing social interaction could be effective. Such a course would have been possible through strong government action, as was done in the Covid response in countries like New Zealand and China. SAGE also considered behavioural science evidence on whether coercing behaviour might lead to fatigue over time. Such a perspective assumed public autonomy in decision making and did not consider policing measures. Thus, SAGE rejected a lockdown and other NPIs as they feared a lack of public compliance.

Despite the limited evidence from the UK, government officials justified the government’s policy by referencing scientific evidence. For example, on 9 March, Johnson emphasised: ‘it’s absolutely critical in managing the spread of this virus that we take the right decisions at the right time, based on […] evidence’ (PMO, 2020b). The words ‘at the right time’ indicate an attempt to balance different considerations: thus, the government sought not to put excessive demands on people’s liberties.

The UK Chief Scientific Officer Patrick Vallance created controversy by endorsing a herd immunity approach. Vallance argued, ‘our aim is to try to reduce the peak, broaden the peak, not suppress it completely; also, because the vast majority of people get a mild illness’ (Parker et al., 2020). This was in opposition to Vallance’s praise for China on an earlier date: ‘the (WHO) has rightly responded quickly, and China has introduced strong public health measures’ (DHSC, 2020).

These conflicting statements reveal the public health and civil liberty dilemma, in which the government leant towards a liberal approach with little government action. Without solid evidence, the government’s reluctance to implement more decisive action fulfils the liberal understanding where curbing civil liberties is unjust without strong evidence (Flood et al., 2020).

This interpretation is further validated by BBC’s reporting of Johnson’s statement on 5 March. He is quoted as stating: ‘one of the theories is perhaps you could take it on the chin, take it all in one go and allow the disease to move through the population without really taking as many draconian measures. I think we need to strike a balance’ (BBC, 2020a; emphasis added). The word ‘draconian’ is in stark opposition to an understanding of such measures as life-saving. The Prime Minister reinforced his aversion by suggesting the possibility of ‘tak[ing] it on the chin’ – a reference to the spread of the disease and the loss of life. This suggests that public health was not prioritised, in deference to a desire to maintain civil liberties.

On 16 March, the UK government escalated its anti-Covid efforts by issuing national recommendations to the public, but these still relied on behavioural nudges. Measures included shielding, which meant that those living with vulnerable people needed to start social distancing. This change to actively advocate for social-distancing measures came following a shift in the evidence provided by SAGE, while the recommendations by the WHO and ECDC supporting restrictions had not changed.

The SAGE meeting minutes on 27 February did not give any recommendations to the government; instead, they listed the evidence (SAGE, 2020a), with the course of action left open to government interpretation. The evidence stated there was no proof of the efficacy of cancelling large events, but social distancing for over 65s effectively reduced deaths, not transmission. However, this evidence was hard to determine without applying restrictions and was in opposition to evidence available from countries such as China.

By 16 March, however, SAGE advocated for social-distancing measures to be introduced immediately and ‘agreed that its advice on interventions should be based on what the NHS [National Health Service] needs […] not on the evidence on whether the public will comply with the interventions’ (SAGE, 2020c: 2). Therefore, while there was no new decisive data from SAGE, there was a change in the approach of introducing government interventions based on the need for public health.

In the daily briefing on 16 March, the government repeated the same objectives as before, but it made more evident the rationale in terms of how it was prioritising public health, stating: ‘our objective is to delay and flatten the peak of the epidemic by bringing forwards the right measures at the right time, so that we minimise suffering and save lives’ and instructed individuals to change their behaviour: stopping non-essential contact with others (PMO, 2020d). Moreover, the Prime Minister again used the term ‘draconian measures’ when referring to these necessary recommendations. The language used was requesting, rather than instructing: ‘if possible, you should not go out even […] If necessary, you should ask for help from others’ (PMO, 2020d). The government was taking more action, but individuals retained primary autonomy.

This changed on 18 March as the cases further increased and the language changed from ‘if possible’ to ‘everyone – everyone – must follow the advice to protect […] the wider public’ (PMO, 2020e). On 22 March, Johnson gave further instructions and justified measures by evoking communitarian values but maintained reference to an evidence-led approach. ‘The more we collectively slow the spread, the more time we give the NHS to prepare, the more lives we will save’ (PMO, 2020g). The narrative changed from ‘many people will die’ to ‘we need to save lives and the NHS’. Therefore, protecting public health became the primary justification but no enforcement policy was introduced. The statements evoked the harm principle, a key rationale for any liberal response (Powers et al., 2012).

The lack of enforcement policy was picked up by many news sources as well. They reported that many found a lack of clarity on what the measures entail. The restrictions were deemed ‘useless if they are undermined by mixed messages’ (O’Grady, 2020). The concern of ‘draconian’ measures was also mirrored by many, reporting a lack of compliance. (Fielding and Allen, 2020; Kuenssberg, 2020a). On the other hand, some criticised the government for the delayed response, and others argued that it was still not enough just to ‘advise’ people (e.g. Chater, 2020; Steel, 2020).

The Prime Minister said in a press conference, ‘most people would accept we are already a mature and liberal democracy where people understand very clearly the advice that is being given to them’ (Peck, 2020). This highlighted the value of liberty in democracies and the responsibility assigned to them on an individual level rather than a paternalistic response. This was also followed by the government denying the ‘herd immunity approach’.

In summary, the government discourse increasingly started justifying fundamental changes in social behaviour, using communitarian values, as well as the harm principle. The confused messaging by the government showed that, while community good was prioritised, individual liberty remained an important consideration. Therefore, while the discourse evoked communitarian values, the policy action remained libertarian.

On 20 March, the government ordered gyms and cinemas to be closed, and on 23 March, they announced a national lockdown. The closures came almost three weeks after the WHO’s recommendation on implementing strong NPIs. The Coronavirus Act became the law, making social distancing mandatory. The lockdown came due to increasing pressure on the health system, with 938 deaths and 11,137 cases (UK Health Security Agency, 2022).

In announcing the closure on 20 March, Johnson stated, ‘I know how difficult this is, how it seems to go against the freedom-loving instincts of the British people’ (PMO, 2020f). Johnson even acknowledged that these measures went against ‘the inalienable free-born right of people born in England to go to the pub’ (Stewart and Walker, 2020). The statements made apparent how integral freedom was to the government’s response despite a public health emergency.

Later, due to the rising number of cases and the increasing pressure on the NHS, the government took decisive action by including policing measures (PMO, 2020h). The government’s justification for the response remained evidence-led.

However, there was still no decisive scientific data to base a policy on. On 18 March, SAGE discussed the implementation of social-distancing measures and concluded that the effects would only be known after a few weeks, depending on compliance (SAGE, 2020d). By 23 March, they concluded that the public had made significant behavioural changes; however, preventing the spread still required further measures to stop the NHS capacity from being overwhelmed (SAGE, 2020e). As the number of cases increased, SAGE recommendations for the response escalated.

Similarly, the ECDC emphasised the need for social-distancing measures by school and workplace closures, and so on. However, they emphasised that ‘societal norms and values underpinning freedom of movement and travel will need to be weighed against precautionary principles and the public acceptance of risks’ (ECDC, 2020d: 5). The quote indicates that there was always a concern to balance liberties with public health even within scientific research. This is as per liberalism, which attempts to do the same in this dilemma.

To convey the urgency, the framing of the policy response also escalated. The justification of the response became more hyperbolic as the virus now became ‘the invisible killer’ (PMO, 2020h). Furthermore, the coronavirus became ‘the biggest threat this country has faced for decades’. Stopping hospitals from becoming overwhelmed became the primary justification, and the global threat was considered now with reference to the impact on the Italian health care system. These references were unlike the previous justifications, which only focused on the national impact.

The lockdown announcement involved the government providing concise statements on what the citizens were required to do. The language was of collective responsibility as the government created a core policy and the public was told: ‘stay at home, protect the NHS, and save lives’ (PMO, 2020h). The slogan was repeated in every following statement until the end of the lockdown.

These measures received a mixed response. Despite the lockdown, many criticised the lack of clarity in the rules for the public, and people remained confused with what the limits to their freedom were (Mason et al., 2020; ‘ The Guardian view on lockdown…’, 2020). Others were concerned about the restrictions on liberty, stating ‘anyone who cares about democracy and civil liberty should not welcome such responses’ (McDonald, 2020). Another headline lamented the ‘End of Freedom’ (King, 2020). Yet many praised the response as there were still many steps that the government was not using, such as ‘curfews or travel bans’ (Kuenssberg, 2020b). This was attributed to the deep concern for liberty, with many arguing ‘while the instruction to stay at home was necessary, it went against the prime minister’s deepest instincts’, ‘who is an optimistic liberal at heart’ (BBC, 2020b).

To summarise, the government policy discourse was both liberal and communitarian when the government announced the lockdown. The concern for interfering with people’s liberty, through repeated mentions, was evident, and the harm principle was evoked to justify curbing liberties. In this, however, the government took strong paternalistic measures, including policing. The discourse was community-led, but the action remained informed by strong liberal values.

The early response to Covid-19 across different countries involved a variety of approaches: many countries took swift and strict action, while others (e.g. Sweden) decided against immediate restrictions. This discrepancy in the responses poses questions regarding the importance of liberal values for democracies in the face of public health emergencies. This paper explored the UK government’s response to Covid-19 in terms of the emerging conflict between public health and civil liberties.

The analysis found the UK response to be strongly influenced by libertarianism. This may have also been motivated by other factors in decision making, such as economic considerations (although many link individual liberty to neoliberalism) or a political legacy. However, I am taking these as separate issues because of the importance of the value of liberty in democracies, whereby the paper aimed to uncover the role of ethical values given the dichotomy presented to nations during the emergency period. This dichotomy is best evaluated through a value-ridden lens.

Throughout the first few months of 2020, officials framed the UK government’s policies as being evidence-led and emphasised the need to prioritise public health above all. However, in conducting an IPA, this paper has made clear that the scientific evidence available at this time was largely uncertain, with conflicting recommendations from scientific bodies. Furthermore, in both the Prime Minister’s statements and the ECDC and SAGE documents, liberal social norms were an essential consideration in recommending strong measures. While the WHO urged stronger action throughout, SAGE advice was found to be conflicting and rapidly changing. The UK focused on national behavioural evidence and trends for the virus rather than taking global lessons into account. In its effort to conduct what it considered a proportionate response, the government did not impose strict measures until the healthcare system was near collapse.

Some studies have cited changing situation and evidence as the cause for a change in response (Cairney, 2021; Zaki and Wayenberg, 2020). However, through the analysis of policy against available evidence and the use of language, this paper demonstrates that values were a primary concern for the government. By the time the government imposed a lockdown and closed all social venues, it was increasingly evident that restricting liberties was a vital consideration, as the Prime Minister repeatedly mentioned ‘freedom’ and its essential place in British lives. As the pressure increased, the government stopped focusing on the compliance of behavioural nudges and had to implement social-distancing measures. This was opposed to a communitarian response – according to which, preventative measures can be implemented even when there is no definitive evidence for the betterment of the community. Furthermore, other European countries – for example, France and Spain – had even stricter measures than the UK (Nyamutata, 2020), despite ECDC reports calling for assessment of impact on liberal values and considering behavioural science. Thus, the qualitative analysis of speeches and the difference in response between liberal democracies considering similar evidence (behavioural science) demonstrates that the impact to liberty was a key consideration resulting in policy.

Given the liberal values influencing UK’s inaction, this paper argues that communitarian values – that is, public health – should be prioritised over liberty in times of emergency. The UK Commons Health and Social Care, and Science and Technology parliamentary committees concluded hundreds of thousands of lives could have been saved if the UK imposed a lockdown a week earlier and called the response ‘one of the most important public health failures the United Kingdom has ever experienced’ (UK Parliament, 2021). In particular, the first three months were criticised for the government not acting on the precautionary principle considering limited evidence. This suggests that in times of emergency, the preventative principle needs to be applied rather than to wait for evidence.

To understand policy decisions further, future studies can explore how values play a role in policymaking of other countries and explore patterns within democracies. Within UK health policy, communitarian and liberal underpinnings can be explored in the vaccination and surveillance programmes. It is hoped that future studies in this direction will help us understand the theoretical underpinnings of policies.

| Artefacts | Community of meaning | Identifying the discourse | Identifying the conflicts | Emerging themes |

| Hand washing: 20 seconds | Protect others Avoid others | Testing is important Help the NHS | Avoid unnecessary gatherings | Nudging and preventative behaviour |

| Closing the school suggestions | Reaching the target of carrying out 25,000 test a day | Calling back the retired doctors | Shortage of doctors and help Unprecedented challenge | Forming national recommendations and implementing a lockdown |

Bacchi, C. 1999. Women, Policy and Politics: The Construction of Policy Problems. Stanford:Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Baggott, R. 2010. Public Health: Policy and Politics. Stanford: Macmillan International Higher Education.

Baggott, R. 2015. Understanding Health Policy. 2nd edn, Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Bambra, C. 2009. Changing the world? Reflections on the interface between social science, epidemiology and public health. J Epidemiol Community Health, 63 (11), 867–68.

BBC, 2020a. Coronavirus: UK moving towards ‘delay’ phase of

virus plan as cases hit 115. [Online] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-51749352

[Accessed 30 March 2021].

BBC, 2020b. Newspaper headlines: UK ‘under house arrest’ as

coronavirus measures ‘end freedom’, available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-the-papers-52013243

[Accessed 4 April 2021].

Belin, C. and Maio, G. D. 2020. ‘Democracy after coronavirus: Five challenges for the 2020s’. The Brookings Institution, available at https://www.brookings.edu/research/democracy-after-coronavirus-five-challenges-for-the-2020s/

Bhattacherjee, A. 2012. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices. Textbooks Collection 3rd edn, Florida: Global Text Project.

Brody, B. A. 1993. Liberalism, communitarianism, and medical ethics. Law & Social Inquiry, 18 (2), 393–407.

Brownson, R. C., Fielding, J. E. and Maylahn, C. M. 2009. Evidence-based public health: A fundamental concept for public health practice. The Annual Review of Public Health, 30, 175–201.

Cairney, P. 2021. The UK government’s COVID‑19 policy: Assessing evidence‑informed policy analysis in real time. British Politics, 16, 90–116.

Cairney, P. and Oliver, K. 2017. Evidence-based policymaking is not like evidence-based medicine, so how far should you go to bridge the divide between evidence and policy? Health Research Policy and Systems, 15 (35), 1–11.

Cetron, M. and Landwirth, J. 2005. Public health and ethical considerations in planning for quarantine. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 78, 325–30.

Chadwick, A. 2000. Studying political ideas: A public political discourse approach. Political Studies, 48, 283–301.

Chater, N., 2020. People won’t get ‘tired’ of social

distancing – the government is wrong to suggest otherwise. The Guardian.

Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/16/social-distancing-coronavirus-stay-home-government

[Accessed 4 April 2021].

Cheibub, J. A., Hong, J. Y. and Przeworski, A. 2020. Rights and deaths: Government reactions to the pandemic, SSRN, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3645410 [Accessed 4 April 2021].

Childress, J. F. and Bernheim, R. G. 2003. Beyond the liberal and communitarian impasse: A framework and vision for public health. Florida Law Review, 55 (5), 1191–20.

Childress, J. F and R. R Faden, 2002. Public health ethics: Mapping the terrain. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 30 (2), 170–77.

DHSC, 2020. ‘CMO for England statement on the Wuhan novel

coronavirus’,.Gov.UK, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/cmo-for-england-statement-on-the-wuhan-novel-coronavirus

[Accessed 1 April 2021].

ECDC, 2020a. Guidelines for the Use of Non-Pharmaceutical Measures to Delay and Mitigate the Impact of 2019-nCoV, Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

ECDC, 2020b. Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Increased Transmission Globally – Fifth update, Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

ECDC, 2020c. Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: Increased Transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK – Sixth update, Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

ECDC, 2020d. Considerations Relating to Social Distancing Measures in response to COVID-19 – Second update, Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Faden, R., Bernstein, J. and Shebaya, S. 2020. ‘Public health ethics’, in E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 Edition). Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Fafard, P. 2015. Beyond the usual suspects: Using political science to enhance public health policy making. J Epidemiol Community Health, 69, 1129–32.

Fahlquist, J. N. 2020. The moral responsibility of governments and individuals in the context of the coronavirus pandemic. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 1–6.

Fielding, J. and Allen, P. 2020. ‘British nationals will be

banned from France if Boris Johnson does not adopt the same coronavirus

policies as the EU’. Daily Mail,

available at: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8122895/France-lies-City-streets-country-deserted-country-enters-strict-lockdown.html

[Accessed 5 April 2021].

Fischer, F. 2003. Reframing Public Policy: Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online.

Flood, C. M., MacDonnell, V., Thomas, B. and Wilson, K. 2020. Reconciling civil liberties and public health in the response to COVID-19. FACETS, 5, 887–98.

Forster, J. L. 1982. A communitarian ethical model for public health interventions: An alternative to individual behavior change strategies. Journal of Public Health Policy, 3 (2), 150–63.

Gostin, L. O. and Hodge, J. G. 2020. US Emergency legal responses to novel Coronavirus. JAMA, 323 (12), 1131–32.

Gray, G. and Jones, M.D. 2016. A qualitative narrative policy framework? Examining the policy narratives of US campaign finance regulatory reform. Public Policy and Administration, 31 (3), 193–220.

Hickman, T., Dixon, E. and Jones, R. 2020. Coronavirus and civil liberties in the UK. Coronavirus and Civil Liberties in the UK, 25 (2), 151–70.

King, V. 2020. ‘Coronavirus briefing: UK crackdown and WHO

warning on “accelerating” pandemic’. BBC, available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-52010707

[Accessed 4 April 2021].

Kuenssberg, L. 2020a. ‘Coronavirus: UK’s already huge

changes may just be the start’. BBC, available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-51969659

[Accessed 6 April 2021].

Kuenssberg, L. 2020b. ‘Coronavirus: Strict new curbs on

life in UK announced by PM’. BBC, available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-52012432

[Accessed 5 April 2021].

Lawrence, R. J. 2020. ‘Responding to COVID-19: What’s the problem?’. Journal of Urban Health, 97, 583–87.

Leeuw, E. d., Clavier, C. and Breton, E. 2014. ‘Health policy – why research it and how: Health political science’. Health Research Policy and Systems, 12 (55), available at https://health-policy-systems.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1478-4505-12-55, accessed 5 April 2021

MacIntyre, S. 2011. Good intentions and received wisdom are not good enough: The need for controlled trials in public health. J Epidemiol Community Health, 65, 564–67.

Marginson, S. 2020. The relentless price of high individualism in the pandemic. Higher Education Research & Development, 39 (7), 1392–95.

McDonald, S. M. 2020. We can’t let the coronavirus lead to

a 9/11-style erosion of civil liberties. The Guardian, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/23/coronavirus-civil-liberties-authoritarian-measures

[Accessed 5 April 2021].

Mill, J. S. 1859. On Liberty. 2012 edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Myers, N. 2016. Democracy, rights, community: examining ethical frameworks for federal public health emergency response. Public Integrity, 18(2), 201–26.

Nyamutata, C. 2020. ‘Do civil liberties really matter during pandemics?’ International human rights law review, 9, 62–98.

O’Grady, S. 2020. ‘Boris Johnson needs a lesson in the

basics of coronavirus communication – but the daily briefings are a start’.

Independent, available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/coronavirus-boris-johnson-uk-cases-symptoms-latest-a9404401.html

[Accessed 10 April 2021].

Oliver, T. R. 2006. The politics of public health policy. Annual Review Public Health, Volume 27, 195–233.

Orzechowski, M., Schochow, M. and Steger, F. 2021. ‘Balancing public health and civil liberties in times of pandemic’. Journal of Public Health Policy, 42, 145–53.

Parker, G., Pickard, J. and Hughes, L. 2020. ‘UK’s chief scientific adviser defends ‘herd immunity’ strategy for coronavirus’. Financial Times, 13 March 2020.

Parmet, W. E. 2003. Liberalism, communitarianism, and public health: comments on Lawrence O. Gostin’s lecture. Florida Law Review, 55 (5), 1221–40.

Peck, T. 2020. At this most desperate hour, Britain

desperately needs better than Boris Johnson. Independent, available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/boris-johnson-coronavirus-latest-chris-whitty-press-conference-a9405356.html

[Accessed 4 April 2021].

Petrini, C. 2010. Theoretical models and operational frameworks in public health ethics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7, 189–202.

PHE, 2021. Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK..Gov.UK, available

at: https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/cases

[Accessed 1 April 2021].

PMO, 2020a. ‘Prime Minister’s statement on coronavirus

(COVID-19): 3 March 2020’. Gov.UK, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-at-coronavirus-press-conference-3-march-2020

[Accessed 20 March 2021].

PMO, 2020b. ‘Prime Minister’s statement on coronavirus

(COVID-19): 9 March 2020’. Gov.UK, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-on-coronavirus-9-march-2020

[Accessed 1 April 2021].

PMO, 2020c. ‘Prime Minister’s statement on coronavirus

(COVID-19): 12 March 2020’. Gov.UK, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-on-coronavirus-12-march-2020

[Accessed 30 March 2021].

PMO, 2020d. ‘Prime Minister’s statement on coronavirus

(COVID-19): 16 March 2020’. Gov.UK, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-on-coronavirus-16-march-2020

[Accessed 30 March 2021].

PMO, 2020e. ‘Prime Minister’s statement on coronavirus

(COVID-19): 18 March 2020’. Gov.UK, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-on-coronavirus-18-march-2020

[Accessed 3 March 2021].

PMO, 2020g. ‘Prime Minister’s statement on coronavirus

(COVID-19): 22 March 2020’. Gov.UK, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-on-coronavirus-22-march-2020

[Accessed 30 March 2021].

PMO, M. O., 2020f. ‘Prime Minister’s statement on

coronavirus (COVID-19): 20 March 2020’. Gov.UK, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-on-coronavirus-20-march-2020

[Accessed 4 April 2021].

PMO, M. O., 2020h. Prime Minister’s statement on

coronavirus (COVID-19): 23 March 2020. Gov.UK, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-address-to-the-nation-on-coronavirus-23-march-2020

[Accessed 4 April 2021].

Powers, M., Faden, R. and Saghai, Y. 2012. Liberty, mill and the framework of public health ethics. Public Health Ethics, 5 (1), 6–15.

Reynolds, M. 2020. ‘Boris Johnson’s brief love affair with

science is well and truly over’. Wired, available at: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/uk-government-boris-johnson-science-advisors

[Accessed 25 March 2021].

Mason, R. S. Murphy, S. Morris, N. Parveen and L. O’Carroll

(2020), ‘No 10 criticised after unclear lockdown advice confuses public’. The

Guardian, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/mar/24/police-ready-to-enforce-uk-public-transport-lockdown-if-needed

[Accessed 6 April 2021].

SAGE, 2020a. ‘SAGE 11 minutes: Coronavirus (COVID-19)

response, 27 February 2020’. Gov.UK, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sage-minutes-coronavirus-covid-19-response-27-february-2020

[Accessed 30 March 2021].

SAGE, 2020b. ‘SAGE 13 minutes: Coronavirus (COVID-19)

response, 5 March 2020’. Gov.UK, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sage-minutes-coronavirus-covid-19-5-march-2020

[Accessed 1 March 2021].

SAGE, 2020c. ‘SAGE 16 minutes: Coronavirus (COVID-19)

response, 16 March 2020’. Gov.UK, available at: at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sage-minutes-coronavirus-covid-19-response-16-march-2020

[Accessed 30 March 2021].

SAGE, S. A. G. f. E., 2020d. ‘SAGE 17 minutes: Coronavirus

(COVID-19) response, 18 March 2020’. Gov.UK, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sage-minutes-coronavirus-covid-19-response-18-march-2020

[Accessed 3 April 2021].

SAGE, S. A. G. f. E., 2020e. ‘SAGE 18 minutes: Coronavirus

(COVID-19) response, 23 March 2020’. Gov.UK, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sage-minutes-coronavirus-covid-19-response-23-march-2020

[Accessed 4 April 2021].

Schmitter, C. and Karl, T. L. 1991. What Democracy Is… and Is Not. Journal of Democracy, 2 (3), 75–88.

Sisnowski, J. and Street, J. M. 2008. Evidence-Informed Public Health Policy. International Encyclopedia of Public Health, 527–36.

Smith, K. 2013. Beyond Evidence Based Policy in Public Health: The Interplay of Ideas. Stanford: Springer.

Steel, M., 2020. How convenient for Boris Johnson that the

science on coronavirus ‘changed’ – that way he was never wrong. Independent.

Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/coronavirus-boris-johnson-schools-cruise-restaurant-theatre-a9411961.html

[Accessed 4 April 2021].

Stewart, H. and Walker, P. 2020. ‘Coronavirus UK: Boris

Johnson announces closure of all UK pubs and restaurants’. The Guardian,

available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/20/london-pubs-cinemas-and-gyms-may-close-in-covid-19-clampdown

[Accessed 4 April 2021].

‘The Guardian view on lockdown for Britain: necessary

hardship’ (2020), The Guardian, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/23/the-guardian-view-on-lockdown-for-britain-true-leadership-is-required

[Accessed 5 April 2021].

Turoldo, F. 2009. Responsibility as an ethical framework for public health interventions. American Journal of Public Health, 99 (7), 1197–201.

UK Health Security Agency, 2022. ‘UK Coronavirus Dashboard’.

Gov.UK, available at: https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/cases?areaType=nation&areaName=England

[Accessed 1 May 2022].

UK Parliament, 2021. ‘Coronavirus: Lessons learned to date.

Sixth report of the Health and Social Care Committee and third report of the

Science and Technology Committee of session 2021’ Gov.UK, available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5802/cmselect/cmsctech/92/9203.htm

[Accessed 1 March 2023].

WHO, 2020a. ‘Archived: WHO Timeline - COVID-19’. [Online]

Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19

[Accessed 1 March 2021].

WHO, 2020b. Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), Stanford: WHO.

Williams, G., Díez, S. M., Figueras, J. and Lessof, S. 2020. ‘Translating evidence into policy during the Covid-19 pandemic: Bridging science and policy (and politics)’. Eurohealth, 26 (2), 29–33.

Yanow, D. 2000. Conducting Interpretive Policy Analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Zaki, B. L. and Wayenberg, E. 2020. ‘Shopping in the scientific marketplace: COVID-19 through a policy learning lens’. Policy Design and Practice, 1–13.

Civil liberty: Freedoms for individuals that are protected through the constitution.

Communitarianism: Defined in the article as a theory that values community welfare over individual liberty.

Draconian: The word draconian can be used to describe laws or rules that are really harsh, extremely severe and repressive. In ancient Athens, Draco was a legislator who made some extremely strict laws.

Harm principle: A central principle to liberalism conceptualised by politcal philosopher, John Stewart Mill, pertaining that individuals should be free to act as they wish unless their actions harm someone else.

Interpretive policy analysis: Dvora Yanow’s method to research and analyse policies through interpreting situated meanings within context.

Liberalism: Defined in the article as a theory that values individual liberties as a fundamental good.

Non-pharmaceutical interventions: Behavioural interventions implemented during Covid-19 rather than the use of medicine to mitigate the virus.

Public health ethics: A study of ethics within public health.

Public health policy: A study of policy-making on public health through a political scientific approach.

Social constructionism: An epistemological position according to which human development is socially situated and knowledge is constructed through interaction with others.

To cite this paper please use the following details: Mujib, M. (2023), 'The Conflict Between Public Health And Civil Liberties: The Initial UK Government Policy Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 16, Issue 1, https://reinventionjournal.org/article/view/978. Date accessed [insert date].

If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.