Kirsten Scheiby, University of Warwick

This article analyses Sondheim and Weidman’s Assassins to explore the way in which historical events are transformed into mythology. Following Barthes’ (1972) Mythologies, I propose that Assassins demonstrates how mythology simplifies history to serve a dominant narrative. Assassins creates a dialogue between contrasting historical narratives through the Balladeer, who embodies a simplified mythology, providing ironic contrast to Sondheim’s complex characterisation of the assassins. The characterisation of Guiteau provides an example to examine Sondheim’s character in comparison with historical and fictional accounts, in order to appreciate how mythology alters the perception of this figure. The scene with Lee Harvey Oswald invites discussion of cultural mythologies defining American national identity: the American Dream, independent freedoms and gun culture. These mythologies arise from historical mythology, but also through commodity fetishism and conspiracy theories.

Assassins restores the complexity of characters who are otherwise reduced by mythology to consider how cultural mythology leads to the formation of these assassins, and to challenge the biased narrative of American historical mythology. By comparing Assassins to the historical accounts and folk songs it references, we can better understand the role of mythology in Assassins, illuminating the process by which historical mythology is produced, and indeed produces the fictionalised assassins.

Keywords: Stephen Sondheim’s Assassins, American assassins, US Presidential Assassinations, historical mythology, American musical, Stephen Sondheim

The 1990 off-Broadway musical Assassins, with music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim and book by John Weidman, explores the long-popular mythology of assassination stories as they manifest in contemporary American society by depicting an anachronistic performance of songs and dialogue between nine assassins and attempted assassins of the Presidents of the United States. The cultural interest in assassin stories relates to their unique subject matter: the term ‘assassination’ is used in reference to the murder of a powerful or politicised figure – thus assassinations are distinctly public in their impact. Looking specifically at the modern American culture out of which Sondheim’s Assassins is created, we can clearly see an ongoing public obsession with the mythology of Presidential assassinations in historical study, amateur detective work (or conspiracy theories), and artistic and cultural renderings.

In his seminal book Mythologies, Roland Barthes identifies myth as the language used in reference to mythological subjects, whereby myths capture the dominant perspective which comes to be accepted as ‘natural’ truth (1972: 109, 129). Additionally, we might understand myths as being those narratives or subjects that penetrate a society to the point where they are instantly familiar and become emblematic of that society’s ideals and collective identity. These myths are produced through an accumulation of the various narratives found in historical account, media and artistic interpretations, which together create an overarching mythology in the cultural conscience. Constructing a narrative is core to mythology: as with President Kennedy, whose image was ‘constructed through a series of hero tales that, told and retold, produced a politician as the hero of an unfolding mythology’ (Hellmann, 1997: ix). Hellmann elaborates that history ‘recorded particular stumbles and failures’, whereas the produced mythology ‘preserved […] the meaning of John F. Kennedy’ (Hellmann, 1997: 146). Where Kennedy is mythologised as a ‘hero’, his assassin is consequently characterised as the villain. This American mythology encourages patriotic celebration of the martyred Presidents while vilifying the assassins and simplifying their stories and motives.

The mythologies of US history and culture are inserted into Assassins – predominantly through the plot and characters, but also through intertextual references to popular American writers, patriotic music and projections of iconic visual images of pertinent historical moments. Sondheim investigates this American historical mythology[1] by creating a dialogue between the mythologised versions of history and an imagined demythologised account. Since mythology reduces the complexity of historical events, the American assassins are generally mythologised as being archetypal ‘madmen’ shooters, and the villains of America,[2] rather than real people with complex inner lives and frightening motivations.[3]

This article analyses Sondheim’s Assassins through the lens of mythologising history, looking at how the musical uses characterisation, intertextuality and musical pastiche to explore the relationship between history and mythology. By comparing the musical to the historical accounts on which it is based, we can better understand how history is transformed into mythology, and how these narratives interact within Assassins. I argue that Sondheim and Weidman craft a dialogue between these narratives to demythologise certain patriotic ideologies that are presented as natural truths in America – such as the American Dream, individual freedoms, and gun culture. Moreover, Sondheim’s exploration of the production of mythological narratives informs the argument that the assassins themselves are produced by these myths in a cycle of myth being told and retold.

Assassins considers American historical mythology from an alternative and challenging perspective, encouraging its audience to interrogate the perceived ‘nature’ of these patriotic ideologies – to the extent that it was initially rejected by critics who struggled with its counter-cultural and seemingly anti-American sentiment. However, by reading Assassins as an exploration of the production and reception of mythology and ideology, we can better appreciate how the musical grapples with the significance of American myths and national identity.

The narrative of Assassins is shaped by the looming presence of the Balladeer: a transcendent, timeless figure who sings cheery ballads about three of the four successful assassins – ’The Ballad of Booth’, ‘Czolgosz’, and ‘Guiteau’. The Balladeer’s tone, both musically and textually, captures that of many traditional American folk songs, incorporating themes of optimistic patriotism, the American Dream and sometimes acting as cautionary tales with a Christian moral. This style captures the voice of American mythology – as Sondheim, on the Balladeer’s purpose, stated:

myths and historical stories are […] primarily passed down through story and song, so [we] thought it would be useful to have a balladeer who would sing folk songs throughout the show: the received wisdom of what’s happened in American history

In this way, the Balladeer documents the assassins’ mythologies by collecting and reciting the received narratives of these historical events. Each ballad serves to cast this political history as a simplistic tale of heroes and villains. As Barthes writes, in turning history to nature, myth ‘abolishes the complexity of human acts’ (1972: 143): thus mythology does not serve to create a false history, but naturalises a biased perspective as the truth. As we will see, through the Balladeer, Assassins investigates both the mythological version of each assassin – whereby they are reduced to the ‘madman’ lone shooter with simplistic motivations – while also unveiling demythologised versions: crafting three-dimensional characters out of the reductionist myth, thereby restoring their complexity as disenfranchised individuals with very real, frightening motivations.

The Balladeer’s role as storyteller and mythologist is established in the opening verse of ‘The Ballad of Booth’:

BALLADEER.

Someone tell the story,

Someone sing the song.

Every now and then

The country

Goes a little wrong.

Every now and then

A madman’s

Bound to come along.

Doesn’t stop the story—

Story’s pretty strong

With this verse, Sondheim celebrates the power of storytelling, highlighting the importance of stories and folk songs in preserving history. This prelude establishes the Balladeer’s characterisation, embodying a mythology that glorifies the narrative of America as a unified ‘story’. Through this patriotic characterisation, the national consequences of horrific acts of violence are undercut as something going ‘a little wrong’, trivialising the influence of these assassins. A key component in assassination mythologies is the incomprehensible loss, leaving many asking, ‘how could one inconsequential angry little man cause such universal grief and anguish?’ (Sondheim, 2011: 113). Yet the Balladeer undermines the power these assassins sought, his trivial tone asserting that their violent interference and inflicted grief cannot alter America’s story. Thus the Balladeer’s verse is a patriotic homage to the country’s strength in the face of national tragedy and a celebration of America’s national identity. However, it must be acknowledged that the myth of American patriotism is heavily racialised, and the Balladeer’s narrative awkwardly avoids discussing the Civil War: Booth is condemned as a ‘traitor’, but not as a racist. This epitomises the danger of over-simplifying historical narratives, as the received wisdom of American mythology excludes any voices that differ from its ideal.

Through the Balladeer, Assassins is able to craft its own complex, humanised versions of American history’s greatest villains, while still exploring the biased characterisation found in the received wisdom of historical mythology. Weidman has said that their purpose was not to make audiences ‘sympathise’ nor ‘empathise’ with the assassins, but to merely recognise them as being ‘multidimensional and complicated’ individuals with conviction behind their abhorrent acts (Sondheim et al., 1991b: 00:04:40). This characterisation allows for a fascinating interaction between multiple historical narratives, as the ‘real’ assassins are allowed to interact with the patriotic mythology embodied by the Balladeer. Each character is depicted with a desire of how they want to be remembered, while the Balladeer mocks them with the contradictory reality of how the myth of American history remembers them:

BALLADEER.

But traitors just get jeers and boos,

Not visits to their graves,

While Lincoln, who got mixed reviews,

Because of you, John, now gets only raves

This tension fuels the ironic humour of the Balladeer’s role, as the conversation between the past itself and historical mythology highlights the inconsistencies between these narratives, setting Booth’s egotism and lack of self-awareness against the mythological perception of Booth as a ‘traitor’. Even as Booth tries to convince us of his ideological motivations, the Balladeer contradicts his narrative by repeatedly asserting that Booth acted for petty, personal reasons, such as negative theatre reviews.

This contrast is emphasised by the ternary form of ‘The Ballad of Booth’, with the Balladeer’s upbeat ‘A’ section, accompanied by banjo, juxtaposed by Booth’s rubato, mournful aria in the ‘B’ section. Booth’s assertion of his ideological conviction and lack of remorse as he takes his life is abruptly followed by a return to the Balladeer’s upbeat melody, with the outrageously funny line ‘Johnny Booth was a headstrong fellow, / Even he believed the things he said’ (Sondheim and Weidman, 1991a: 22). Both the lyrics and musical style serve to create humour and undercut Booth’s ideology, once again reducing his characterisation to the historical mythology of Booth as a foolish and stubborn traitor. Sondheim has noted that it is vital to ‘set off the dispassion of the balladeer and the passion of Booth’ (Sondheim et al., 1991b: 00:24:05), highlighting the contrast between the complex, emotional Booth and the Balladeer as a dispassionate embodiment of mythology. Moreover, the Balladeer’s reductionist, taunting treatment of characters such as Booth is a means to refuse these assassins the aggressive power they sought. Sondheim employs this technique throughout the show, as the Balladeer’s restless optimism and upbeat folk melodies create irony through their inappropriate tone for such dark, violent subject matter.

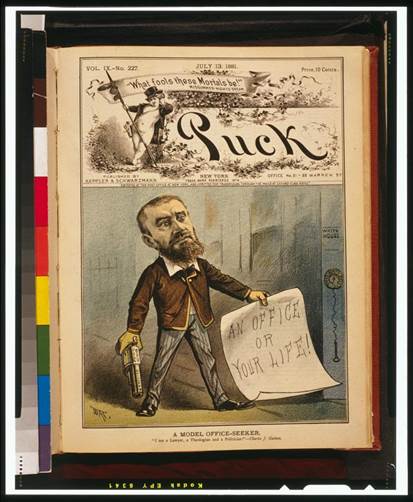

The musical’s dialogue between contrasting narratives is most pertinent in ‘The Ballad of Guiteau’, sung by the Balladeer and Charles Guiteau as he mounts the scaffold to be hanged. To understand the different narratives at play in this scene, we must examine the historical accounts and cultural legacy that together produce the myth of Guiteau. An enigmatic narcissist with various unsuccessful careers, Guiteau assassinated President Garfield in July 1881 after becoming convinced he was owed a diplomatic office, or that God had commanded him to shoot the President (Ayton, 2017: 102, 109). Guiteau pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, and his erratic and obliviously sanguine behaviour during his trial garnered much public interest and debate over whether he was truly as ‘insane’ as he seemed, or whether this was an act to gain attention and reduce his sentence (Rosenberg, 1968: 77, 175). This shapes the historical mythology as it characterises Guiteau: an 1881 political cartoon published in Puck magazine shows a caricatured Guiteau clutching a gun in one hand, in the other a sign, ‘An Office or Your Life!’, accompanied by the sarcastic caption ‘A model office-seeker’ (see Figure 1). This cartoon shows that, even at the time, Guiteau came to be seen less as a dangerous and malevolent killer, but rather a comical caricature of the archetypal ‘madman’ shooter. Meanwhile, a traditional American folk song, ‘Charles Guiteau’, belittles and criticises Guiteau’s demeanour on trial: ‘I tried to play off insane / but found it would not do’ (Kelly Harrell and the Virginia String Band, 1997). Certainly, Guiteau has long been an unusual mythological figure of American history, simultaneously characterised as being ‘insane’, but also sane, a foolish man, but also a ‘cool calculating’ criminal (Rosenberg, 1968: 77).

This historical mythology of Guiteau as a ‘madman’ allows him to fulfil the archetypal role of the theatrical clown in Assassins. Weidman’s characterisation captures the unrelenting optimism of Charles Guiteau, as he consistently provides comic relief to the intense troubles of the other assassins, cheerily reminding them to ‘look on the bright side’ (Sondheim and Weidman, 1991a: 66). While his fellow assassins are overwhelmingly disillusioned with the myth of the American Dream, Guiteau resolutely believes there is hope; as he tells Czolgosz, ‘You know your problem? You’re a pessimist. […] This is America! The Land of Opportunity!’ (Sondheim and Weidman, 1991a: 27). Guiteau’s persistent faith in America’s possibilities positions him in a similar comedic role to that of the Balladeer, providing an ironic contrast to the cynical assassins. In this way, Guiteau’s characterisation remains confined to that of the mythologised Guiteau for much of the show, showing little complexity in favour of fulfilling the comic’s dramatic role. This initial depiction matches not only the historical perspective of Guiteau, but potentially his own perception of himself, as he said to the jury during his trial: ‘I am not here as a wicked man, or as a lunatic. I am here as a patriot’ (Guiteau, 1882: 108). While Sondheim and Weidman certainly depict Guiteau as being psychologically distressed, Guiteau’s self-assertion that he was first and foremost a ‘patriot’ rings true in his dialogue with fellow assassins.

Yet ‘The Ballad of Guiteau’ observes a transformation in Guiteau’s character from the theatrical clown to a fearful man facing his mortality. In this number, Guiteau dances between embodying the mythological caricature of a ‘lunatic’ and a complex character with a frightening ambition who grapples with surging emotions as he nears his death. This is achieved through Sondheim’s use of various intertextual references in the song, drawing attention to the contrasting narratives within historical mythology. Guiteau opens the song with an unaccompanied solo refrain that recurs at the end of each verse – ’I am going to the Lordy’ – the lyrics of which are taken from a poem the real Guiteau wrote and recited the morning of his execution (Sondheim, 2011: 134). In quoting Guiteau’s own words, Sondheim’s fictionalised character is able to embody the voice of the historical Guiteau. The repeated mantra of ‘I am going to the Lordy, I am so glad’ in both Guiteau’s poem and Sondheim’s song is characteristic of Guiteau’s persistent optimism, even as he faces death. However, as the song progresses, Sondheim’s musical setting subverts our perception of the ever-cheery Guiteau: the key modulates higher at the end of each iteration of this refrain, with Guiteau’s vocal pitch moving up a step as he physically steps closer to the scaffold, articulating his growing uncertainty. By singing increasingly higher in his vocal range, Guiteau’s song emulates the infantile tone of the poem, his ‘shrill’ intonation demonstrating his increasing sense of fear (Sondheim and Weidman, 1991a: 67 [stage direction]).

Sondheim’s sorrowful, hesitant and hymn-like melody for Guiteau’s poem is an unsettling contrast to our previous impression of Guiteau as relentlessly cheerful. As Valerie Schrader notes, the musical’s non-chronological structure indicates a clear decision to ‘[give] the audience time to connect with the more likeable Guiteau’ (2017: 330). Indeed, by the time his ballad comes into the show, the audience have formed a stronger connection to Guiteau – not that he is necessarily a sympathetic figure, but his role as the comic relief certainly leads audience members to often look to Guiteau for comfort amid the show’s more dismal scenes. As such, it is all the more disturbing when Guiteau ceases to provide this comic relief, and we are left to face the reality of Guiteau as a killer without solace. His mantra of ‘look on the bright side’ becomes less assertive, exposing this optimism as a façade that conceals the anger and anguish beneath.

While Guiteau sings his own words, the Balladeer’s verses contain intertextual allusions to the folk song, thereby capturing the received mythology about Guiteau:

Come all you tender Christians

Wherever you may be

And likewise pay attention

To these few lines from me

and

BALLADEER.

Come all ye Christians

And learn from a sinner:

Charlie Guiteau

While narrated from different perspectives, both songs give the impression of being a morality tale, that ‘all’ Christians might heed the warning of Guiteau’s sinful misdeeds. In this way, both songs paint Guiteau as a character in a fable, further mythologising the man and distancing his memory from the reality of his acts. This ‘Christian’ perspective of each song (particularly in Sondheim’s version) also alludes to Guiteau’s religious fanaticism, disparaging his conviction that he acted on God’s instruction by instead presenting Guiteau as a paradigmatic ‘sinner’. In changing the first-person narration of the folk song to the Balladeer’s omniscient third-person perspective, Sondheim distances this narrative from Guiteau’s perspective to highlight the contrasting renderings of Guiteau within the historical mythology.

Just as with the lyrics, Sondheim’s use of musical pastiche creates a patchwork of intertextual references, combining ‘three popular song types – the parlor waltz, the cakewalk, and the hymn’ (Lovensheimer, 2000: 14). The musical stylings of a hymn reinforce the ironic contrast between Guiteau’s blasphemous beliefs and the morality-tale style found in the lyrics. Meanwhile, the use of different dance styles articulates Guiteau’s erratic mania as he jumps between the upbeat cakewalk and lethargic waltz. The waltz is a recurring musical style throughout the show, while the cakewalk is unfamiliar and unusual, highlighting Guiteau’s abnormal and eccentric character.

In summary, ‘The Ballad of Guiteau’ combines the narratives of Guiteau’s own words, American folk song and Sondheim’s original lyrics to create a musical and lyrical pastiche of the indiscernible man, Guiteau. This blend of styles and narratives explores Guiteau’s mania, as well as illustrating the different narratives of perception of Guiteau as they blend together to portray one complex human being among the myriad of mythologies informing our understanding of the man.

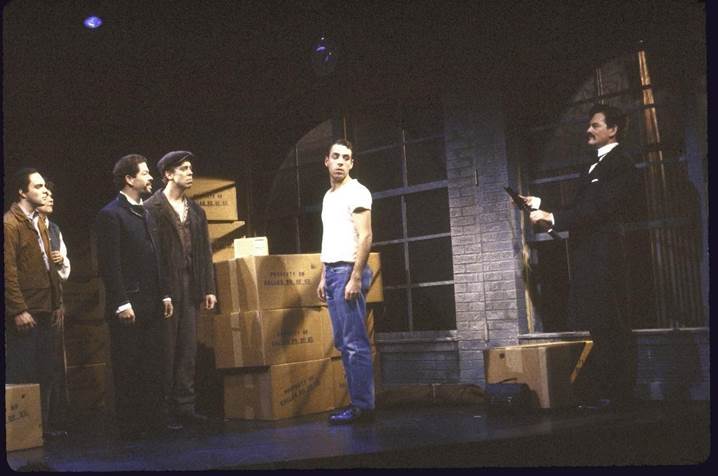

The climax of the musical comes at Scene 16: Lee Harvey Oswald in the Texas School Book Depository on the morning of 22 November 1963. It is logical that this scene provides the dramatic pinnacle of the show given its poignancy in recent history – especially for the original 1990 production of Assassins, the grief of Kennedy’s assassination was within living memory for the majority of audiences. The dramatic intensity of this scene is heightened by the show’s structure, since Oswald is the only character to not appear in any previous scenes; as such, the audience are somewhat distracted by the whimsical display of seemingly larger-than-life characters. The audience are gradually drawn into the mythology of these assassins who seem more removed from present-day reality, until Oswald’s reveal is a startling reminder of an assassin who made a devastating impact on the nation within their own lives. Accounts of the original production demonstrate how set design can intensify the dramatic interpretation of this historic event: as artistic director André Bishop recalled, ‘when the Dallas Book Depository set was revealed' – the only completely detailed setting in a spare, abstract design’ – it ‘inevitably evoked gasps of surprise and occasionally horror’ (1991: ix). This illustrates the ability of visual images to signify myths, and the profound power of this image of the Book Depository to encapsulate a public memory and evoke such reactions (see Figures 2 and 3).[4]

Figure 2: Exhibition space, the sixth-floor

storeroom of the Texas School Book Depository in Dallas, Texas. The open window

to the right shows where Oswald was allegedly perched when he fired at the

President. Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress.

Figure 2: Exhibition space, the sixth-floor

storeroom of the Texas School Book Depository in Dallas, Texas. The open window

to the right shows where Oswald was allegedly perched when he fired at the

President. Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress.

Figure 3: Scene 16 – A storeroom on the sixth floor

of the Texas School Book Depository, from Assassins’ 1990 production.

Lee Harvey Oswald (portrayed by Jace Alexander) stands in the centre in his

recognisable jeans and white T-shirt, while John Wilkes Booth (right, portrayed

by Victor Garber) entices him with the rifle as the other assassins (left) look

on. Photograph by Martha Swope, 1991, New York Public Library.

Figure 3: Scene 16 – A storeroom on the sixth floor

of the Texas School Book Depository, from Assassins’ 1990 production.

Lee Harvey Oswald (portrayed by Jace Alexander) stands in the centre in his

recognisable jeans and white T-shirt, while John Wilkes Booth (right, portrayed

by Victor Garber) entices him with the rifle as the other assassins (left) look

on. Photograph by Martha Swope, 1991, New York Public Library.

Scene 16 marks the culmination of the various mythologies presented throughout the show: not just those of various assassins, but indeed the cultural mythologies defining the American experience and national identity. One such myth is that of the neoliberal free market and capitalism, the ideologies of which have become synonymous with the American Dream of wealth and success (Churchwell, 2018: para. 8.11). Sondheim connects this with the American mythology of gun culture in the earlier ‘Gun Song’:

CZOLGOSZ

A gun kills many men before it’s done,

Hundreds,

Long before you shoot the gun:Men in the mines

And in the steel mills,

Men at machines,

Who died for what?

Czolgosz’s condemnation here of exploitative labour is informed by his experiences as a wage-labourer in brutal factory conditions (Sondheim and Weidman 1991a: 26–27). We might analyse this verse through the lens of commodity fetishism, as Sondheim captures the alienation of the modern production process that separates workers from one another and their ‘finished product’ through specialised labour, as with the miners, millworkers and machine operators (Lukács, 1971: 88). With commodity fetishism, the ‘social character of men’s labour appears to them as an objective character stamped onto the product of that labour’ (Lukács, 1971: 86) so, in this case, the gun seems to hold the essence of these social relations between workers and the production process. By bringing together each stage of production into the narrative of one song, Sondheim demystifies the process of alienation, revealing the full picture of exploitation and inhumane working conditions that go into the making of a gun: an object so glorified in American mythology, yet simultaneously invoking contentious debate.

Indeed, ‘The Gun Song’ enters the debate around gun ownership in America, conveying the voices of four characters most entranced by the gun’s fetish. To see these assassins, who have committed awful acts of violence, fawning over their guns is a terrifying portrayal of the dangers of mythologising guns. The musical style of this song as a barbershop quartet – another quintessential American form – shows that guns are a distinctly Americanised commodity fetish, and a marked aspect of the nation’s mythological identity. Czolgosz’s claim that ‘a gun kills many men before it’s done’ (Sondheim and Weidman, 1991a: 49) is arguably a response to the cliché often invoked by advocates of the second amendment, such as the NRA: ‘guns don’t kill, people do’ (Fletcher, 1994: 6). Thus the Marxist perspective of the production process depicted in this song subverts the argument that guns are ‘not dangerous by themselves’ but only when they are misused (Fletcher, 1944: 6), by showing that even before the commodity of the gun is finished, it leads to the deaths of miners and factory workers. For a gun owner with violent intentions, such as the assassins, these lives sacrificed in production adds to the fetishism of this commodity, as the gun seems to contain the power of the deaths it has already caused and will go on to inflict.

This exploration of commodity fetishism posits that one object – in this case, the gun – is formed by the interweaving relations of workers at each stage of the production process.[5] As such, the gun as a weapon is produced by the lives sacrificed in its production. I argue that this notion presented in ‘The Gun Song’ lays the theoretical groundwork for the show’s climax in Scene 16, as each of the assassins materialise in the Book Depository to convince Oswald to shoot President Kennedy. Just as the gun is the product of the lives that came before it was fully formed, so too, Sondheim and Weidman suggest, is the assassin produced by all the assassins who came before him:

CZOLGOSZ. (Indicating pre-Oswald Assassins)

You’re going to bring us back.HINCKLEY. (Indicating post-Oswald Assassins)

And make us possible.

With this pinnacle anachronistic scene, Sondheim and Weidman present a seemingly supernatural explanation for what really happened that day. Sondheim has stated ‘the idea [was] that all these myths have somehow coalesced and have caused that last scene’ (1991b: 00:20:38), reinforcing how this scene follows on from the themes of ‘The Gun Song’, in showing the Kennedy assassination and its mythology to be produced by many myths. Textual references to ‘The Gun Song’ emphasise the immense power the gun bestows upon the assassin – a key theme of assassin mythologies. As Booth tells Oswald, ‘all you have to do is move your little finger’ (Sondheim and Weidman, 1991a: 101). Booth likens the destructive power contained within the fetishised gun to ‘Pandora’s box’, a statement that positions Oswald at a turning point in history (Sondheim and Weidman 1991a: 101).[6] Thus the presence of past and future assassins emphasises the monumental impact of this historical moment, both politically and culturally, as being the culmination of past mythologies and the genesis of future assassination attempts.[7]

The Kennedy assassination is still surrounded by intrigue, a matter only heightened by Oswald’s murder three days later (Brotherton, 2015: 126).[8] With such historical events, it is somewhat inevitable that conspiracy theories abound – a fact that Assassins alludes to as Booth encourages Oswald:

BOOTH.

Fifty years from now they’ll still be arguing about the grassy knoll, the mafia, […] but this – right here, right now – this is the real conspiracy.

The lack of satisfying answers about the Kennedy assassination – did Oswald truly act alone, and why did he do it – intensified public attention and doubts about the official story, leaving plenty of space for speculation. It is through these conspiracy theories that members of the public create a fiction for themselves to explain the unknowable aspects of this historical and national trauma. As psychologist Rob Brotherton informs us, conspiracy theories emerge from a cognitive bias where we seek to transform ‘chaos into order’ (2015: 11). I propose that conspiracy theories act in a similar way to mythologies, and are themselves integral to the mythology of the Kennedy assassination. Conspiracy theories allow an individual to search for answers in the overwhelming array of questions that remain about the Kennedy assassination, just as fictional and artistic interpretations of those events can allow creators and audiences a sense of catharsis from the uncertainty and disorder. Not only is the Kennedy assassination a popular subject for amateur sleuths and conspiracy theorists, but it is also the subject of frequent fictional adaptation.[9] All of these mythological reinventions serve to ‘recreate public memory’ (Schrader, 2017: 327) of an event that was so publicly traumatic. With Scene 16, Sondheim and Weidman present their own conspiracy theory as to what happened that day: although the appearance of the ghost of John Wilkes Booth to recruit Oswald is an impossible claim, the overarching suggestion that Lee Harvey Oswald is produced by a culmination of myths – both the myths of his fellow assassins, and of American ideals of independent freedoms and the right to pursue one’s dreams – invents an explanation that might satisfy some of the many unanswered questions as to why Oswald took the action of killing the President.

Assassins explores the myths that define America’s national identity from the perspective of mythical individuals considered adversaries to American ideals, subverting patriotic ideas about America’s heroes and villains. Mythology can reinforce patriotism by uniting people against the common enemy of ‘what is opposed to [the nation]’ (Barthes, 1972: 158) – as such, American national identity is defined in opposition to its mythologised villains. However, Assassins encourages the audience to consider that these great villains of American history were not necessarily opposed to American values, nor were they external from the American experience, but are a part of it. As Weidman has said, Assassins portrays an America ‘whose most cherished national myths, at least as currently propagated, encourage us to believe that in America our dreams not only can come true, but should come true’ (cited in Bishop, 1991: xi), thereby critiquing the individualistic ideals of the American Dream. Many of the assassins are portrayed to be disillusioned by the American Dream, yet retaining the conviction that, as Americans, they have the ‘right’ to pursue their ‘dreams’ (Sondheim and Weidman, 1991a: 13). As such, while rallying against these mythologised antagonists might reinforce American patriotism, Assassins shows that the assassins were not ‘outside [of] the American experience’ (Sondheim et al., 1991b: 00:04:55) but themselves participants in these American myths. This shatters the illusion that America can be defined in opposition to the assassins, revealing instead how the very beliefs many Americans hold dear – of the American Dream, of individual freedoms, of the right to own a gun – might just be ideologies that enabled these assassins. This idea is captured by the moment in Scene 16 when a trio of American assassins not featured in the show – Arthur Bremer, Sirhan Sirhan and James Earl Ray – call out to Oswald from ‘somewhere in the house’ (Sondheim and Weidman, 1991a: 99 [stage direction]). By placing these extra assassins among the audience, a sinister message is conveyed that these assassins are not as different from the ordinary American as mythology would have us believe, and that they could even be lurking among us. Following the attack on the US capitol in January 2021, it is evident that acts of domestic terrorism (particularly when committed by white Americans) can be perceived as wholly patriotic; a disturbing paradox that truly reveals the underlying violence in these myths of American patriotic ideology.

The mythology of assassinations is a

popular subject in American culture due to the frequent attempts to kill the US

President throughout history, which invoke public outrage and uncertainty. The

difficulty in comprehending these historical acts of violence leads to the

reinvention of history through both conspiracy theories and artistic

adaptations, ultimately creating a historical mythology. With Assassins,

Sondheim and Weidman use drama and music to explore the received wisdom of

popular American mythologies and mythological figures. Assassins

examines the identity of America as a nation by interrogating the mythologies

that define it, particularly the historical mythologies that position the

assassins as America’s enemies. These figures are perceived to be in opposition

to American ideals, thus hatred of them reinforces the myths of the American

Dream and patriotism. By creating a more complex, demythologised

characterisation of each assassin, we are allowed a greater understanding of

their motives; this ultimately challenges the idea that these people acted in

opposition to American ideals, suggesting instead that American mythologies

such as individual freedoms and gun culture in part produced these assassins.

With the role of the Balladeer and the techniques of intertextuality and

musical pastiche, a dialogue is created between the complex versions of the

assassins and the received wisdom of American history, or the dominant

mythology through which America’s history is purported as a unified story of

American patriotism. Thus Sondheim and Weidman craft an incredibly nuanced

exploration of mythology, utilising a wide array of intertextual references to

explore the contrasting narratives that form the mythologies of American

history and culture. By reinventing their own version of this mythology,

Sondheim and Weidman challenge the audience to become aware of our own received

biases and interrogate the national and historical mythologies defining the

society in which we live.

Figure 1: ‘A Model Office-Seeker. “I am a Lawyer, a Theologian and a Politician!” – Charles J. Guiteau’, Puck, 13 July 1881. Image in the public domain, available through the Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/92508892/, accessed 30 March 2021.

Figure 2: ‘Exhibition space, the sixth-floor storeroom of the Texas School Book Depository in Dallas, Texas’. Image in the public domain, Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/2014632037/, accessed 10 April 2021.

Figure 3: Scene 16 of the Playwrights Horizons production of Assassins, featuring actors (L-R) Eddie Korbich, Debra Monk, Jonathan Hadary, Terrence Mann, Jace Alexander & Victor Garber. (New York, 1991). Photo by Martha Swope ©The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

[1] The term ‘historical mythology’ is used here to recognise that the received wisdom of history presents a biased, dominant narrative.

[2] The public hatred of the assassins as America’s enemies or villains is seen in the crimes of passion of Jack Ruby, who murdered Lee Harvey Oswald, and John A. Mason and William Jones, attempted assassins of Charles Guiteau. Jones in particular received huge public support, and both he and Mason were pardoned of their crimes, highlighting their differential treatment from that of Guiteau. See Ayton (2017: 107–08).

[3] I use scare-quotes when referring to the assassins as ‘madmen’, or similar synonyms, to note that these are outdated, medically imprecise terms that carry ableist connotations – however, when looking at the historical context through which each assassin lived, many were perceived as ‘insane’, largely due to the historical misunderstanding of psychopathology.

[4] It is arguably for this same reason that the Texas Book Depository has preserved the sixth-floor window as a museum exhibit, recreating how it looked on that day (JFK.org, n.d.).

[5] Raymond Knapp similarly writes that the song demonstrates ‘how one gun connects backward to the many lives it consumes in its manufacturing, and forward to the “just one more” it might consume’ (Knapp, 2005: 169). Indeed, the idea here of consumption connects powerfully to the song’s Marxist themes of commodification and exploitation of workers. Yet I wish to suggest the song goes further than connecting the gun to the lives it takes, but indeed that the gun contains and is produced by these social relations.

[6] ‘Pandora’s Box’ may also be an allusion to Samuel Byck’s failed attempt to assassinate Richard Nixon. Byck named his plan – to hijack a commercial airliner and crash it into the White House, in order to kill President Nixon – ‘Operation Pandora’s Box’. See Clarke (2012: 131–33).

[7] The decision by some productions of Assassins to cast one actor as both the Balladeer and Oswald adds further significance to this interpretation. (Such productions include the 2004 Broadway revival directed by Joe Mantello, and the 2021 Classic Stage Company production directed by John Doyle). The optimistic Balladeer, having been chased off the stage by the embittered assassins in ‘Another National Anthem’, reappears as Lee Harvey Oswald, his optimism shattering to disillusion after exposure to the assassins’ cynicism. This casting emphasises the notion of mythology being produced and, simultaneously, the assassin being produced by this mythology. The Balladeer as mythologist observes and documents American mythologies, thereby constructing and then becoming Lee Harvey Oswald: the recipient of these myths.

[8] Both because Oswald’s murder by Ruby may give the appearance of a conspirator being silenced by a co-conspirator, and because his death prevented a thorough investigation and trial. With Oswald dead, we will never hear his testimony or come to understand his motivations, preventing closure for all who were emotionally affected by the assassination.

[9] The assassination of President Kennedy is such a popular subject for fictional adaptation that there is even a sub-genre of science fiction following the use of time travel to prevent Kennedy’s death. For examples, see Britt (2017); Dyke (2000); Green (1990); Hallemann (2020). On the rise of literature of conspiracy and paranoia following Kennedy’s assassination, see Melley (2020).

Ayton, M. (2017), Plotting to Kill the President: Assassination attempts from Washington to Hoover, Dulles: Potomac Books

Barthes, R. (1972), Mythologies, trans. A. Lavers, London: Jonathan Cape Ltd (originally published by Editions du Seuil in 1957)

Bishop, A. (1991), ‘Preface’, in Sondheim, S. and J. Weidman, Assassins, New York: Theatre Communications Group Inc, pp. vii–xi

Britt, R. (2017), ‘6 Science fiction explanations for JFK’s assassination’, Inverse.com, 26 October 2017, https://www.inverse.com/article/37792-jfk-assassination-scifi-conspiracy-theories-quantum-leap-xfiles, accessed 3 April 2021

Brotherton, R. (2015), Suspicious Minds: Why We believe conspiracy theories, New York: Bloomsbury

Buckingham, S. (2010), 'Call in the women', Nature, 468, 502

Churchwell, S. (2018), Behold, America: A history of America First and the American Dream, London: Bloomsbury Publishing

Clarke, J. W. (2012), Defining Danger: American assassins and the new domestic terrorists, New York: Routledge

Fletcher, C. D. (1994), Guns Don’t Kill, People Do: The NRA’s case against gun control, University of Canterbury, http://dx.doi.org/10.26021/3980, accessed 2 April 2021

Guiteau, C. J. (1882), The Truth, and The Removal, https://archive.org/details/truthremoval00guit, accessed 24 June 2021

Hallemann, C. (2020), ‘Why is science fiction so obsessed with the assassination of John F. Kennedy?’, Town & Country, 9 August 2020, https://www.townandcountrymag.com/leisure/arts-and-culture/a33513567/jfk-kennedy-assassination-time-travel-movies-shows/, accessed 3 April 2021

Hellmann, J. (1997), The Kennedy Obsession: The American Myth of JFK, New York: Columbia University Press

JFK.org (n.d.), ‘History of the Texas School Book Depository Building’, The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza, https://www.jfk.org/the-assassination/history-of-the-texas-school-book-depository/, accessed 5 April 2021

Kelly Harrell and the Virginia String Band (1997), ‘Charles Guiteau’, in Smith, H. (ed.), Anthology of American Folk Music [CD], United States: Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Knapp, R. (2005), The American Musical and the Formation of National Identity, Princeton: Princeton University Press

Lovensheimer, J. (2000), ‘Unifying the plotless musical: Sondheim’s Assassins’, Institute for Studies in American Music Newsletter, 29 (2), 5,14

Lukács, G. (1971), History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics, trans. R. Livingstone, London: The Merlin Press Ltd (originally published as Geschichte und Klassenbewußtsein – Studien über marxistische Dialektik by Malik-Verlag in 1923)

Melley, T. (2020), ‘Conspiracy in American narrative’, in Butter, M. and P. Knight (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories, London: Routledge, Chapter 4.4

Rosenberg, C. E. (1968), The Trial of the Assassin Guiteau: Psychiatry and law in the gilded age, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press

Running Against Time (1990), Directed by B. S. Green, [Television Movie], United States: MCA Television Entertainment

Schrader, V. L. (2017), ‘“Another national anthem”: public memory, Burkean identification, and the musical Assassins’, New Theatre Quarterly, 33 (4), 320–32, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266464X1700046X, accessed 22 March 2021

Sondheim, S. and J. Weidman (1991a), Assassins, [Libretto], New York: Theatre Communications Inc

Sondheim, S., J. Weidman and L. Sherman (1991b), Assassins: A conversation piece, Video conversationpieceTM, Directed by R. Englander, New York: Conover Production Services

Sondheim, S. (2011), Look, I Made a Hat: Collected lyrics (1981–2011) with attendant comments, amplifications, dogmas, harangues, digressions, anecdotes and miscellany, New York: Alfred A. Knopf

Timequest (2000), Directed by R. Dyke, [Film], United States: Ardustry

Cakewalk: a dance style originating in African American communities in the mid-19th century

Pastiche:an artistic work which imitates the style of another work, genre or period

Ternary form: a musical form characterised by an opening “A” section, followed by a contrasting “B” section, before returning to the “A” section

To cite this paper please use the following details: Scheiby, K. (2022), 'The Relationship Between History and Mythology in Sondheim and Weidman’s Assassins', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Special Issue | Reeling and Writhing: Intertextuality and Myth, https://reinventionjournal.org/article/view/879. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.