Helen J. Yesberg, University of Queensland

This article examines the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns on the consumption of free digital books, paying particular consideration to the financial advantages and disadvantages for the authors of those books and the libraries supplying them. It investigates trends in the consumption of digital books through both library and piracy sites, sourcing information from librarian reports and the anti-piracy company MUSO, which tracks visits to piracy sites. This research demonstrates that the tense library–publisher relationship is not stable and does not hold up under stress, emphasising the need for an appropriate solution to be developed. It also spotlights the impacts of COVID-19 on authors, some of the most vulnerable members of the publishing community.

Keywords: Impact of COVID-19 on the digital publishing industry, digital book piracy, piracy during COVID-19 lockdowns, eBook restrictive licensing, Internet Archive, controlled digital lending

Over the last 20 years, the digital side of the publishing industry has gone through a rapid phase of development, particularly with respect to pricing, access and distribution of digital books (McKiel and Dooley, 2014; Whitney and de Castell, 2017: 6–22). While the commercial models for distributing traditionally published eBooks have become relatively stable (Herther, 2018), the models for distributing free digital media still remain in a phase of experimentation and innovation. The onset of COVID-19 has exacerbated these industry shifts. The lockdowns imposed across many nations changed the ways that people access free digital media, but the specifics of these changes and their consequences for the industry are not yet well-documented. Changes to both the accessibility and demand for free digital media potentially create significant consequences for all members of the publishing community, including authors, publishing companies, librarians and readers. An evaluation of these changes and consequences will allow us to identify vulnerable members of the community. It may also allow us to predict the direction of future changes within the industry.

To assess the impact of COVID-19 on the availability and consumption of free digital books, both legal and illegal, we must first examine the situation as it was prior to March 2020. Legal acquisition of free books – digital or otherwise – is most commonly mediated by libraries. A patron wishing to access an eBook for free can visit a library’s website and digitally check out the text or join the holds list if all available copies are already in use. This process can occur from home or anywhere else with an Internet connection. It gives the patron immediate access to the eBook once it has been returned by the previous user. The patron then has access to the digital file for the period of the loan, although the software typically prevents certain functions such as copying and pasting the text for piracy prevention reasons. Libraries license, rather than purchase, eBooks from publishers at an inflated price compared to retail. This allows lending of the eBooks to patrons, one reader at a time, often with limitations on how long the library may loan the eBook or how many times it may be loaned (Sang, 2017: 4). Restrictive licensing is justified by publishers to compensate for the easier access of eBooks by library patrons, which putatively causes library eBooks to pose a greater threat to retail sales than physical library resources (Richards, 2020: 2). The intention is to prevent library eBook lending from undermining or ‘cannibalising’ retail sales, and also to generate profit from library loans themselves (Richards, 2020: 3, Whitney and de Castell, 2017: 11). However, the terms make it difficult for libraries to acquire electronic resources (Sang, 2017: 4). A mid-2019 survey showed that 91 per cent of Australian libraries were discontent with the licensing conditions and cost of their eBook providers (ALIA, 2020b). The issue rose to prominence in late 2019, when major publishing house Macmillan imposed a controversial eight-week embargo on new titles in the USA, preventing libraries from licensing more than one electronic copy for two months after the release of a book in order to salvage commercial sales (Sargent, 2019). This was met with outrage and even boycotting from libraries (Albanese, 2019).

Due to the dissatisfaction on both sides, restrictive licensing models are a key aspect of the digital publishing industry requiring further development. Scholarship is divided on the value of restrictive models. Discussion is generally either in support of the librarian position (e.g. Enis, 2018; Giblin et al., 2019; Jones, 2020) or the publisher position (e.g. Authors Guild, 2019b; Richards, 2020; Sargent, 2019). Librarian-favouring researchers offer a range of arguments for their position. Former librarian Kelly Jensen (2019) hypothesises that restrictions such as Macmillan’s eight-week embargo support only authors who are already bestsellers, suggesting that such licensing terms reflect corporate greed for profits rather than true empathy for struggling authors. Access to information, the Internet and eBooks can be considered a human right (Harpur and Suzor, 2014; Jones, 2020), and some argue that restrictive licensing models infringe thereupon by limiting accessibility across the community (Jones, 2020; Widdersheim, 2014). Critiquing the commercialisation of library eBooks by vendors, Widdersheim (2014) asserts that restriction of a digital resource to one patron at a time creates a ‘false scarcity of an abundant resource’, as digital file-sharing has the capacity to be effectively limitless. He views the one-copy, one-user model as an ethically indefensible ‘anachronism from the analog world’ (Widdersheim, 2014). Notably, these more radical anti-restrictive licensing opinions often fail to comment on the matter of author compensation for the hard work of writing a book.

Readers seeking free entertainment may not always choose to obtain that entertainment legally. Piracy is defined as the unauthorised use or reproduction of a copyrighted or patented work (HarperCollins, 2010, ‘Piracy’). Piracy of fiction usually occurs online, via sites such as pdfdrive.com and epub.pub. Illegally sourced content offers several advantages over libraries: no membership is required, there are no waitlists or borrowing limits, and access to the content can be permanent. Piracy of eBooks therefore serves readers’ immediate interests. As readers skirt the cost of legitimate book purchasing, however, authors and publishers miss out on what might have been profits from a legitimate sale. Therefore, it is commonly accepted that blatant digital piracy displaces eBook sales by reducing the incentive for readers to pay for content (Kukla-Gryz et al., 2020; Reimers, 2016; Taylor and Taylor, 2006), although the putative effects of piracy are difficult to experimentally confirm (Smith and Telang, 2016: 85). Most researchers agree that file-sharing and digital piracy were almost certainly responsible for the music industry’s implosion in the early 2000s due to this displacement effect, since almost all incentive for listeners to pay for content was lost (Kurt, 2010; Whitney and de Castell, 2017: 9). Following this example, publishing houses were initially cautious about committing to the digital hemisphere of the industry.

Outside the academic forum, some argue that piracy in fact constitutes free advertising, and actually boosts sales (Grady, 2020; San Francisco Examiner, 2019). In theory, piracy increases accessibility for readers to discover a new favourite author whose books they will subsequently purchase. A 2020 consumer survey found that book pirates are ‘avid’ readers and are 40 per cent more likely than the general population to purchase books (Noorda and Berens, 2021), lending some credibility to this theory. However, even assuming the self-survey results to be accurate, this does not disprove the displacement effect, since it is entirely possible that pirates would purchase an even greater number of books if piracy were impossible. Commonly cited direct evidence (Grady, 2020) for the pro-piracy position includes an over-extrapolation of results from a 2014 study, which found a statistically insignificant increase in video game sales with piracy (van der Ende et al., 2014: 149).

Most academic, peer-reviewed literature disagrees. Although randomised experiments are almost impossible to conduct, the majority of indirect and observational studies to date indicate a reduction in sales (Reimers, 2016; Smith and Telang, 2016: 85). In a Facebook post, prolific Young Adult author Maggie Stiefvater criticised the suggestion that piracy is helpful, describing her own experience with piracy hurting sales of the third novel in The Raven Cycle series that almost resulted in its cancellation (Stiefvater, 2017). She reported that a subsequent effort to keep illegitimate PDF versions of the fourth book at bay was successful at boosting eBook and print sales while it lasted, preventing her publishing house from cancelling the remainder of the series. As an informal experiment, Stiefvater’s experience provides compelling (if anecdotal) evidence that piracy can indeed displace book sales, with significant consequences for the author. It should be noted that for a front-list author with a new release such as Stiefvater, the theoretical ‘free publicity’ that piracy might provide is negligible. For authors in a different position, piracy may result in a different balance of benefit and harm, which cannot be interpreted from Stiefvater’s experience. Additionally, Stiefvater’s young, Internet-savvy reader-base may be more capable of piracy than readers of other genres; hence, this evidence is most applicable to the YA genre.

Occupying the grey area between legitimate libraries and blatant piracy, some organisations offer free access to digital books yet bypass restrictive licensing models. Of primary interest is the non-profit Internet Archive, which offers digital access to books it owns physically via the Open Library endeavour using the controlled digital lending (CDL) framework (Adams, 2020). Essentially, this framework employed by the Internet Archive allows libraries that legally own the physical copy of a text to scan that text and then loan the digital scanned file to patrons in lieu of the physical copy, without the caveats and costs associated with an eBook licence (Adams, 2020). However, the legality of the CDL model is murky. Its legal and ethical basis hinges on the premise of a ‘loaned to owned’ ratio of one; the total number of loans (both physical and digital) can at most be equal to the number of legally owned print copies (Bailey et al., 2018). For instance, if a library utilising CDL had purchased or been donated one physical copy of A Game of Thrones, which they then scanned to their digital collection, one patron could check out the digital copy of A Game of Thrones. Until that copy was returned, no patron could check out A Game of Thrones either physically or digitally, thus maintaining an appropriate ‘loaned to owned’ ratio. The Statement for CDL declares it a ‘good-faith interpretation of US copyright law’ (Bailey et al., 2018).

Many authors and publishers consider this method of bypassing restrictive licensing terms to be piracy (International Publishers Association, 2019; Preston, 2020), labelling it ‘theft’ (McKay, cited in Flood, 2019) and ‘neither controlled nor legal’ (Authors Guild, 2019a); however, librarians’ opinions often differ. Professor Michelle Wu of Georgetown University Law Library frames CDL as simply an effort to ensure libraries can continue to offer ‘legitimately acquired material’ in a relevant format (Wu, 2019). Because the usage of CDL is restricted to non-profit libraries, and because the author of CDL-loaned books receives compensation for the initial hard-copy sale, she argues that CDL is valid under copyright law and that it does not disrupt the market (Wu, 2019). In opposition, Douglas Preston of the Author’s Guild declared the Internet Archive to be piracy in disguise, and that CDL ‘[is] called ‘stealing’ (Preston, 2020). The Association of American Publishers echoed this sentiment, criticising the Internet Archive for distributing ‘bootleg’ copies and accusing them of harming author and publisher royalties (AAP, 2019). The Internet Archive’s use of CDL is an interesting case study in comparing the interests of readers – the noble goal of making all knowledge available to everyone in the world, considered by some a human right (Jones, 2020) – and the interests of authors and publishers, who deserve to be compensated in full for their work. Neither CDL nor the Internet Archive has yet been officially classified as legal or illegal.

As lockdowns were imposed across the globe, requirements for social distancing created a massive demand for digital entertainment. Public libraries adapted quickly to the new COVID-19 requirements by improving access to e-resources (ALIA, 2020a; ALA, 2020). Closures of library spaces were accompanied by a major increase in eBook borrowing. Australian libraries reported increases of up to 300 per cent of the usual monthly eBook borrowing rate (ALIA, 2020c). Since the shutdown on 23 March, as of October 2020, websites of public libraries in New South Wales had been visited over a million times, double their usual traffic (ALIA, 2020c). The surge in popularity of eBook borrowing can be attributed both to existing library patrons migrating to the digital format, and to new patrons joining a library for the first time to cope with the lockdown. Many libraries streamlined their registration protocols to avoid face-to-face security requirements. Ipswich Libraries reported a ‘notable bump’ in library registrations between February and April, and Libraries South Australia welcomed 70 new members a day after the lockdown started (ALIA, 2020a). This trend was not limited to Australia; libraries in Washington, USA saw more than quadruple the rate of new electronic memberships being added upon closure of the libraries in March (Wilburn, 2020), and New York Public Library reported an impressive 864 per cent increase in digital library card applications (Marx, 2020).

By removing the burden of cost from readers, libraries shoulder a significant financial burden themselves. Readers flocking to e-resources placed libraries under increasing pressure during lockdown. Given that libraries cannot loan more copies of an eBook than the number of licences they paid for, the increased demand for popular titles caused waitlists to back up and placed library budgets under ‘severe strain’ (Melady cited in Zeidler, 2020). Children’s books in particular, especially children’s fiction, grew significantly in popularity (ALIA, 2020a; Wilburn, 2020). At a time when a turbulent economy permitted limited increases in government funding at best, and relatively cheap print books were harder both to acquire and to loan, the high price of library eBook licences made it difficult for them to provide services (Sang, 2017: 4). The increased demand for eBook loans prompted many libraries to reallocate funds away from print purchases towards expanding their e-resource collections (ALIA, 2020c; Wilburn, 2020; Zeidler, 2020). This allowed authors and publishers to maintain some profit, even as bookshop closure caused print sales to dwindle early in the lockdown phase (Italie, 2020). However, library budgets were significantly strained.

In response to the pandemic, therefore, major publishing houses – including Macmillan and Penguin Random House – altered the terms of their eBook licensing agreements in libraries’ favour. This often involved cancelling recent fee increases. Macmillan’s controversial eight-week embargo on new releases for library eLoans is a primary example. Following much backlash and even boycotting from libraries (Coan and Parker, 2020), Macmillan abandoned the embargo in mid-March of 2020, and also temporarily reduced some eBook licensing prices to support the expansion of library collections (Sargent, 2020). Penguin Random House and HarperCollins also softened the terms of their eBook licence agreements (Zeidler, 2020). The senior director of public policy of the American Library Association (ALA) lauded the changes, saying that the more flexible terms offered by Penguin Random House allowed libraries to ‘support [their] communities in a period of unprecedented need’ (Inouye cited in ALA, 2020). Individual librarians echoed the sentiment (ALIA, 2020a; Zeidler, 2020). Although readers may not be aware of the fluxing costs of library eBooks, these changes certainly benefitted them, as libraries were better able to cater to their needs. Some benefit likely carried over to authors and publishers, given that libraries were able to purchase more eBooks.

However, the previous high costs and restrictive licensing models were not imposed solely to satisfy corporate greed, contrary to what librarians may suggest. Justifying the implementation of the eight-week embargo in October of 2019, Macmillan CEO John Sargent asserted that almost half of eBook reads in the USA are mediated via libraries, and that for each circulation of a digital library book, Macmillan earns ‘well under two dollars and dropping’ (Sargent, 2019). This reflects a very low rate of compensation for authors. Indeed, at the time the embargo was implemented, libraries were responsible for only 15 per cent of Macmillan’s eBook revenue, despite mediating 45 per cent of eBook reads (Trachtenburg, 2019). The price hikes and tighter restrictions imposed by publishers attempted to improve these conditions for authors, as well as for publishing houses themselves. However, COVID-19 all but required publishers to loosen restrictions and provide eBooks to libraries at lower costs again. This reinstated the initial problem of low compensation per copy, even as libraries licensed more eBooks (ALIA, 2020a). On balance, given the surge in popularity of digital media, the alteration to library licences was quite possibly disadvantageous for publishers and authors, at least in the short term. Admittedly, this is merely an informed guess; gathering data on this phenomenon is difficult, and it remains possible that increased borrowing of eBooks led (or will later lead) to subsequent purchasing of those books by library patrons.

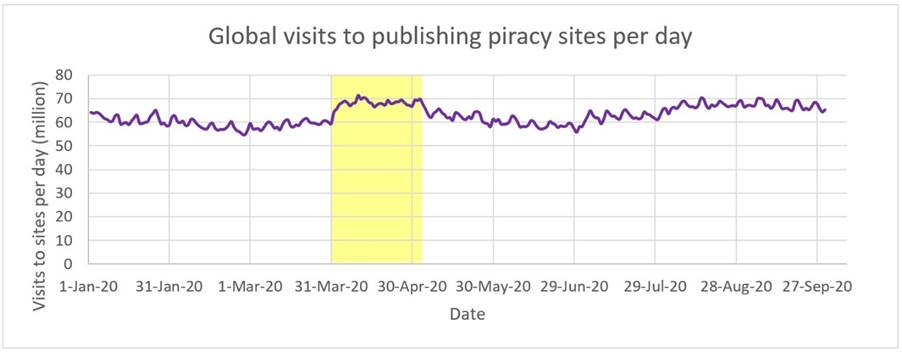

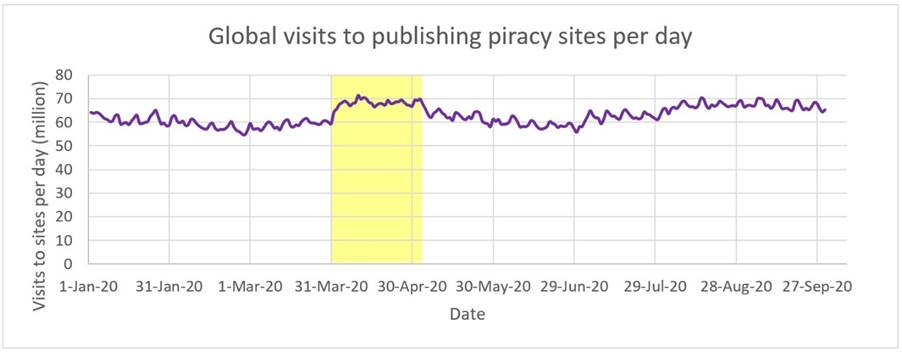

COVID-19 also appears to have increased the incidence of piracy, particularly eBook piracy. In 2020, online piracy spiked in late March, remained high throughout April, and declined again in May (MUSO, 2020), which corresponds with the initial lockdown periods that many countries implemented in the face of COVID-19. Daily visits to piracy sites increased from 350 million (350M) globally in February to 410M in early April, an increase of 17 per cent (see Figure 1). This data, collected from the anti-piracy technology company MUSO, includes visits to piracy sites for film and television, music, games and publishing. Visits to publishing industry-specific piracy sites (primarily sites offering Manga and eBook downloads) also increased by approximately 17 per cent, from 60M between January and March to 70M in early April. Interestingly, the percentage increase in piracy of eBooks was much greater than that for piracy in general. Traffic to the popular eBook piracy site pdfdrive.com spiked by 36 per cent in early April, increasing from 7.5M to 10.2M. This is more than double the increase for piracy across all media formats, which suggests that eBooks became particularly popular for pirating during the lockdown.

What is responsible for the upturn in the relative popularity of eBook piracy? Unlike legal access to free digital media, accessibility of piracy and torrenting sites did not significantly increase during the lockdown. Therefore, the increase in piracy across all media predominantly reflects an increased demand for free digital entertainment. Similarly, the relative popularity of eBook piracy reflects greater demand for free eBooks, either because more people pirated books during the pandemic or because the same population of people visited piracy sites more frequently, or some combination thereof. But why would this occur to a greater extent with books than other media? The answer may relate to lockdowns changing the availability of various book formats. Movies, television and music have all been predominantly digital since long before COVID-19 arose. Books, however, remain popular in print format, and COVID-19 reduced the accessibility of print books. Selective paperback readers – comprising over 70 per cent of the reading population (Watson, 2018) – were confined to exploring new titles digitally thanks to lengthy shipping times (Australia Post, 2020) and the closure of bookstores and libraries. It is reasonable to conclude that some of these readers may have been unwilling to pay for a format they consider ‘substandard’, and therefore turned to libraries and piracy to obtain the content for free rather than purchasing their own eBooks. This could explain the disproportionate increase in piracy of books compared to other media, since their digital-only nature protects music, film and television from this effect.

In response to the pandemic and lockdown, as well as other 2020 events, waitlists were suspended for some digital content. Across the USA in June and July, many anti-racism books were offered as ‘no-hold’ eBooks and audiobooks, donated by Overdrive in support of the Black Lives Matter movement that was greatly active at the time (Grunenwald, 2020). Many of these books proved highly popular; library circulation of anti-racism books spiked by almost 300 per cent in June (Freeman, 2020). In particular, How To Be An Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi circulated on bestseller lists for 18 weeks (New York Times, 2020). Librarians and associated parties have cited Kendi’s commercial success as evidence that access to free library eBooks does not hurt sales, even with concurrent accessibility (Albanese, 2020). This suggestion supports their argument that publishers’ licensing models, which intend to compensate for reduced sales due to library accesses, are unfounded and unfair. It is interesting to consider whether the success of How To Be An Antiracist occurred because of or in spite of its no-hold library availability across the USA. Certainly, the prominence of the Black Lives Matter movement at the time was a major driving factor. It is difficult to assess whether sales would have been impacted (and if so, in which direction) had the book not been donated by Overdrive.

The Internet Archive also chose to suspend waitlists throughout the lockdown, launching the National Emergency Library (NEL) in March. Over 1.4 million books were made available for concurrent access for patrons across the world until the end of June 2020 (Freeland, 2020a). This was intended to address an ‘unprecedented global and immediate need’ for access to digital resources during the pandemic for research and entertainment purposes (Freeland, 2020a). The Internet Archive created the NEL on behalf of disadvantaged students and readers. Accordingly, they reported ‘elation’ (Kahle, 2020) and ‘delight’ (Freeland, 2020b) from teachers, librarians and parents in response. However, authors and publishers were generally much less appreciative. Representatives of the Internet Archive asserted that they ‘made it easy’ for authors to opt-out and withdraw their books from the NEL (Freeland, 2020a); nonetheless, the Author’s Guild called the NEL ‘appalling’ and accused it of ‘hurting authors […] at a time they [could] least bear it’ (Preston cited in Flood, 2020). Nicola Solomon of the UK’s Society of Authors labelled it ‘piracy, pure and simple’ (cited in Flood, 2020). Indeed, the Internet Archive was on shaky legal ground even before launching the NEL, given their use of CDL as a distribution model rather than eBook licensing. The NEL violated CDL’s ‘loaned to owned’ ratio, weakening their legal position further.

Author Barbara Fister supported the Internet Archive’s actions, tweeting that she ‘couldn’t be happier’ about discovering her own books in the NEL (@bfister, 2020). Fister asserted that the Internet Archive has the ‘moral high ground’ for ‘consider[ing] the public good in this crisis’ (Fister cited in Hanamura, 2020). Notedly, Fister’s twenty-year-old novels are no longer offered by most public libraries, meaning that their availability in the NEL conferred more advantage (through increased accessibility, which may recruit new readers) than disadvantage (through lost sales that were relatively infrequent regardless in Fister’s case). Fister is therefore in a different position to many front-list authors who protested the NEL, including Pulitzer prize-winner Colson Whitehead (Flood, 2020). Authors who currently stand to profit from retail sales were theoretically more threatened by the NEL. Evidence is conflicting about how much the NEL, legitimate or not, might have damaged sales. As previously discussed, there is some evidence that piracy displaces sales (e.g. Stiefvater, 2017), at least for front-list authors, and Macmillan’s CEO claimed that even legitimate library eBook loans ‘cannibalise’ sales (Sargent, 2019). Conversely, Ibram X. Kendi’s success proves that free, unlimited digital access does not preclude a book from selling well. Additionally, a 2019 study using Google Books data found that digitisation of public domain books increased sales by 5–8 per cent on average, with a much sharper increase of up to 35 per cent for more obscure works (Nagaraj and Reimers, 2019). Other studies (Eelco et al., 2018; Snijder, 2010) suggest that Open Access scholarly manuscripts sell just as well as their paywalled counterparts. This evidence offers some support to the Internet Archive’s argument that their work is not harmful (Hanamura, 2020), especially to back-list authors like Fister. However, significant differences between the NEL and these studies – Google Books only grants access to out-of-copyright works, and academic monographs are inherently accessible only to a tiny minority of the population – mean these conclusions are far from directly transferrable.

In her support of the NEL, Fister is an outlier among authors and publishers. Indeed, the NEL was cancelled two weeks ahead of schedule due to a lawsuit jointly filed by Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Hatchette, and John Wiley and Sons (Harris, 2020). The lawsuit accuses the Internet Archive of piracy, declaring not just the NEL but also the Internet Archive’s entire mode of operation (including CDL) to be ‘mass copyright infringement’ (Harris, 2020). Fister acknowledged the dubious legality of the NEL but argued that ‘copyright isn’t working as it should’ (Fister cited in Hanamura, 2020), suggesting sub-optimal legal systems are to blame for any conflicts rather than the Internet Archive and its actions. The legal and ethical debate around the Internet Archive and NEL is a manifestation of the conflict between author’s rights to be paid for their work and the public interest – the rights for all people to have equitable access to information. Fair Use is somewhat ambiguous as it applies to CDL, and ethical justifications are reasonable enough on both sides that it is hard to predict the outcome of the court case, which is ongoing at the time of writing (Albanese, 2021; Richards, 2020: 4).

The digital aspect of the publishing industry is changing and developing, and the COVID-19 pandemic induced further changes by increasing demand for free information and entertainment. Visits to both piracy and library sites – with the Internet Archive and its National Emergency Library occupying the grey area in between – spiked during the lockdown months. Overall, the recent changes to free digital media distribution generally seem to disadvantage authors, with increased piracy and lower library licensing costs. Changes brought on by the pandemic have disrupted the balance between protecting the rights of authors and serving the interests of the public. This balance may settle at a new equilibrium as the digital publishing ecosystem adapts. In particular, publishers will need to reassess their eBook licensing terms to maintain a fair and sustainable system for all parties. Additionally, the outcome of the lawsuit filed against the Internet Archive will either confirm or disprove the legality of CDL, potentially changing the digital playing field for book lending permanently.

Many thanks are owed to Dr Helen Marshall, Program Convenor for the Writing Major at the University of Queensland, for her generous and invaluable support, advice and feedback.

Figure 1: Number of visits to publishing piracy sites in all recorded countries per day, from January to September 2020. Yellow indicates the major lockdown period imposed by COVID-19 (March 30–April 31). Data obtained from MUSO.com.

@bfister (2020), ‘I have some books included in the @internetarchive’s National Emergency Library and I couldn’t be happier about it’, Twitter, 15 April 2020, 11:39a.m., available at https://twitter.com/bfister/status/1250493999292522497, accessed 15 October 2020

Adams, C. (2020), ‘Michelle Wu receives Internet Archive hero award for establishing the legal basis for controlled digital lending’, Internet Archive Blogs, 20 October 2020, available at https://blog.archive.org/2020/10/20/michelle-wu-receives-internet-archive-hero-award-for-establishing-the-legal-basis-for-controlled-digital-lending/, accessed 25 October 2020

Albanese, A. (2019), ‘As boycotts mount, Macmillan CEO defends library e-book embargo’, Publishers Weekly, 6 November 2019, available at https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/libraries/article/81666-as-boycotts-mount-macmillan-ceo-defends-library-e-book-embargo.html, accessed 7 February 2021

Albanese, A. (2020), ‘A reset for library e-books’, Publishers Weekly, 9 October 2020, available at https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/libraries/article/84571-a-reset-for-library-e-books.html, accessed 25 October 2020

Albanese, A. (2021), ‘Judge extends discovery deadline in Internet Archive book scanning suit’, Publishers Weekly, 2 December 2021, available at https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/digital/copyright/article/88051-judge-hears-discovery-disputes-in-internet-archive-book-scanning-suit.html, accessed 26 January 2022

ALA (American Library Association) (2020), ‘ALA welcomes Penguin Random House’s expanded library access to ebooks and audiobooks’, 18 March 2020, available at http://www.ala.org/news/press-releases/2020/03/ala-welcomes-penguin-random-house-s-expanded-library-access-e-books-and, accessed 20 October 2020

AAP (Association of American Publishers) (2019), ‘Statement on flawed theory of “controlled digital lending”‘, available at https://publishers.org/news/statement-on-flawed-theory-of-controlled-digital-lending/, accessed 18 January 2021

Australia Post (2020), ‘Coronavirus: international updates’, Updated 17 October 2020, available at https://auspost.com.au/about-us/news-media/important-updates/coronavirus/coronavirus-international-updates, accessed 25 October 2020

ALIA (Australian Library and Information Association) (2020a), ‘COVID-19 and Australian public libraries’, ALIA and Australian Public Library Alliance, 30 April 2020, Deakin, ACT, available at https://read.alia.org.au/covid-19-and-australian-public-libraries-interim-report-30-april, accessed 15 October 2020

ALIA (Australian Library and Information Association) (2020b), ‘A Snapshot of eLending in public libraries’, 3 June 2020, Deakin, ACT, available at https://read.alia.org.au/snapshot-elending-public-libraries, accessed 15 October 2020

ALIA (Australian Library and Information Association) (2020c), ‘Submission in response to the Australia Council for the arts’, Discussion Paper’, 13 October 2020, Deakin, ACT, available at https://read.alia.org.au/alia-submission-response-australia-council-arts-2020c-discussion-paper-october-2020, accessed 14 October 2020

Authors Guild (2019a), ‘Controlled digital lending is neither controlled nor legal’, AG Industry & Advocacy News, 8 January 2019, available at https://www.authorsguild.org/industry-advocacy/controlled-digital-lending-is-neither-controlled-nor-legal/, accessed 17 October 2020

Authors Guild (2019b), ‘Macmillan announces new library lending terms for ebooks’, AG Industry & Advocacy News, 26 July 2019, available at https://www.authorsguild.org/industry-advocacy/macmillan-announces-new-library-lending-terms-for-ebooks/, accessed 18 January 2021

Bailey, L., K. K. Courtney, D. Hansen, M. Minow, J. Schultz and M. Wu. (2018), ‘Position statement on controlled digital lending’, Controlled Digital Lending by Libraries, September 2018, available at https://controlleddigitallending.org/statement, accessed 17 October 2020

Coan, D. and C. Parker. ‘Is the Macmillan boycott working?’ (2020), Readers First, 16 January 2020, available at http://www.readersfirst.org/news/2020/1/16/is-the-macmillan-boycott-working, accessed 21 January 2021

Eelco, F., R. Snijder, B. Arpagaus, R. Graf, D. Kramer and E. Moser (2018), ‘OAPEN-CH – The impact of open access on scientific monographs in Switzerland, a project conducted by the Swiss National Science Foundation’, Zenodo, available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1220607, accessed 26 January 2022

Enis, M. (2018), ‘Librarians react to new PRH terms’, Library Journal, 143 (18), available at https://www.libraryjournal.com/?detailStory=181012PRHebookterms, accessed 20 January 2021

Flood, A. (2019), ‘Internet Archive’s ebook loans face UK copyright challenge’, The Guardian, 23 January 2019, available at https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/jan/22/internet-archives-ebook-loans-face-uk-copyright-challenge, accessed 13 October 2020

Flood, A. (2020), ‘Internet Archive accused of using COVID-19 pandemic as “an excuse for piracy”‘, The Guardian, 31 March 2020, available at https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/mar/30/internet-archive-accused-of-using-covid-19-as-an-excuse-for-piracy, accessed 13 October 2020

Freeland, C. (2020a), ‘Announcing a National Emergency Library to provide digitized books to students and the public’, Internet Archive Blogs, 24 March 2020, available at http://blog.archive.org/2020/03/24/announcing-a-national-emergency-library-to-provide-digitized-books-to-students-and-the-public/, accessed 13 October 2020

Freeland, C. (2020b), ‘Impacts of the temporary National Emergency Library and controlled digital lending’, Internet Archive Blogs, 11 June 2020, available at http://blog.archive.org/2020/06/11/impacts-of-the-temporary-national-emergency-library/, accessed 11 January 2021

Freeman, K. S. (2020), ‘Overdrive releases top trending anti-racism and social justice eBooks’, iMore, 17 June 2020, available at https://www.imore.com/overdrive-releases-top-trending-anti-racism-and-social-justice-ebooks, accessed 21 October 2020

Giblin, R., J. Kennedy, K. Weatherall, D. Gilbert, J. Thomas and F. Petitjean (2019), ‘Available, but not accessible? Investigating publishers’ e-lending licensing practices’, Information Research, 24 (3), available at http://informationr.net/ir/24-3/paper837.html, accessed 4 January 2021

Grady, C. (2020), ‘Why authors are so angry about the internet archive’s emergency library’, Vox, 2 April 2020, available at https://www.vox.com/culture/2020/4/2/21201193/emergency-library-internet-archive-controversy-coronavirus-pandemic, accessed 11 October 2020

Grunenwald, J. (2020), ‘COVID response collections now available’, Overdrive, 16 June 2020, available at https://company.overdrive.com/2020/06/16/covid-response-collections-now-available/, accessed 9 October 2020

Hanamura, W. (2020), ‘Observations from an author and librarian’, Internet Archive Blogs, 4 May 2020, available at https://blog.archive.org/2020/05/04/observations-from-an-author-librarian/, accessed 27 October 2020

HarperCollins (2010), ‘Piracy’, Collins Dictionary, available at https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/piracy, accessed 23 October 2020

Harpur, P. and N. Suzor (2014), ‘The paradigm shift in realising the right to read: How eBook libraries are enabling in the university sector’, Disability & Society, 29 (10), 1658–72

Harris, E. A. (2020), ‘Internet Archive will end its program for free e-Books’, New York Times, 11 June 2020, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/11/books/internet-archive-national-emergency-library-coronavirus.html, accessed 17 October 2020

Herther, N. K. (2018), ‘The latest trends in books, eBooks, and audiobooks’, Information Today, 35 (8), 1, 24–25

International Publishers Association (2019), ‘‘An appeal to readers and librarians from the victims of CDL’, 15 February 2019, available at https://internationalpublishers.org/copyright-news-blog/828-an-appeal-to-readers-and-librarians-from-the-victims-of-cdl, accessed 10 January 2021

Italie, H. (2020), ‘Book sales fall as impact Of Coronavirus increases’, USA Today, 18 March 2020, available at https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/books/2020/03/18/book-sales-fall-impact-coronavirus-increases/2872277001/, accessed 24 October 2020

Jensen, K. (2019), ‘Want to borrow a library eBook? Why it might become more challenging’, Book Riot, 1 November 2019, available at https://bookriot.com/libraries-boycott-ebook-embargos/, accessed 20 January 2021

Jones, E. (2020), ‘Vending vs lending: How can public libraries improve access to eBooks within their collections?’, Public Library Quarterly, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2020.1782702, accessed 4 January 2021

Kahle, B. (2020), ‘The National Emergency Library – Who needs it? Who reads it? Lessons from the first two weeks’, Internet Archive Blogs, 7 April 2020, available at http://blog.archive.org/2020/04/07/the-national-emergency-library-who-needs-it-who-reads-it-lessons-from-the-first-two-weeks/, accessed 10 October 2020

Kukla-Gryz, A., J. Tyrowicz and M. Krawczyk (2020), ‘Digital piracy and the perception of price fairness: Evidence from a field experiment’, Journal of Cultural Economics, available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-020-09390-4, accessed 20 January 2021

Kurt, S. (2010), ‘A happy medium: Ebooks, licensing, and DRM’, Information Today, 27 (2), available at https://www.infotoday.com/it/feb10/Schiller.shtml, accessed 10 January 2021

Marx, A.W. (2020), ‘Libraries must change’, New York Times (Opinion), 28 May 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/28/opinion/libraries-coronavirus.html, accessed 11 October 2020

McKiel, A. and J. Dooley (2014), ‘Changing library operations: Consortial demand-driven eBooks at the University of California’, Against the Grain, 26 (3), 59–61

MUSO.com (2020), ‘Data by industry: Piracy pages tracked’, Data obtained via academic research access permit, 18 October 2020

Nagaraj, A. and I. Reimers (2020), ‘Digitization and the demand for physical works: Evidence from the Google Books project’, SSRN, May 2020, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3339524

New York Times (2020). ‘NYT Bestsellers – Hardcover nonfiction’, 19 July 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/books/best-sellers/2020/07/19/hardcover-nonfiction/, accessed 27 October 2020

Noorda, R. and K. I. Berens (2021), ‘Immersive media and books 2020: Consumer behaviour and experience with multiple media forms’, Portland State University, available at https://www.panoramaproject.org/immersive-media-reading-2020, accessed 26 January 2022

Preston, D. (2020), ‘The pandemic is not an excuse to exploit writers’, The New York Times, 6 April 2020, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/opinion/coronavirus-authors.html, accessed 22 January 2021

Reimers, I. (2016), ‘Can private copyright protection be effective? Evidence from book publishing’, Journal of Law and Economics, 59 (2), 411–40

Richards, K. T. (2020), ‘COVID-19 and libraries: E-books and intellectual property issues’, Congressional Research Service report (Legal Sidebar), 28 April 2020, LSB10453, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10453, accessed 22 October 2020

San Francisco Examiner (2019), ‘Can piracy be a good thing?’, available at https://www.sfexaminer.com/marketplace/can-piracy-be-a-good-thing/, accessed 19 January 2021

Sang, Y. (2017), ‘The politics of eBooks’, International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics, 13 (3), 211–18

Sargent, J. (2019), ‘Macmillan publishers: A change in our eBook terms of sale’, 25 June 2019, available at https://www.publishersweekly.com/binary-data/ARTICLE_ATTACHMENT/file/000/004/4222-1.pdf, accessed 19 October 2020

Sargent, J. (2020), ‘Macmillan publishers: There are times in life when differences should be put aside’, Letter to librarians, authors, illustrators, and agents, 17 March 2020, available at https://www.publishersweekly.com/binary-data/ARTICLE_ATTACHMENT/file/000/004/4353-1.pdf, accessed 20 October 2020

Smith, M. D. and R. Telang (2016), Streaming, Sharing, Stealing: Big Data and the Future of Entertainment, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Snijder, R. (2010), ‘The profits of free books: An experiment to measure the impact of open access publishing’, Learned Publishing, 23(4), 293-301, available at https://doi.org/10.1087/20100403, accessed 26 January 2022

Stiefvater, M. (2017), ‘A story about piracy’, Facebook, 31 October 2017, available at https://www.facebook.com/notes/maggie-stiefvater-really-its-me/a-story-about-piracy/10154994010857036/, accessed 19 October 2020

Taylor, A. and C. Taylor (2006), ‘Pirates ahoy! Publishing, the internet, and electronic piracy’, Entertainment Law Review, 17 (4), 114–17

Trachtenburg, J. A. (2019), ‘Library E-book lending poses rising problem for publishing industry’, Wall Street Journal, 25 July 2019, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/e-books-make-macmillan-rethink-relationships-with-libraries-11564063800, accessed 17 January 2021

Van der Ende, M., J. Poort, R. Haffner, P. de Bas, A. Yagafarova, S. Rohlfs and H. van Til (2014), ‘Estimating displacement rates of copyrighted content in the EU’, Study prepared for the European Commission, available at https://ec.europa.eu/growth/content/study-estimating-displacement-rates-copyrighted-content-eu_en, accessed 10 October 2020

Watson, A. (2020), ‘eBooks: Statistics and facts’, Statista Books & Publishing, 18 December 2018, available at https://www.statista.com/topics/1474/e-books/, accessed 12 January 2021

Whitney, P. and C. de Castell (2017), Trade eBooks in Libraries, Munich, Germany: De Gruyter Saur

Widdersheim, M. M. (2014), ‘E-lending and libraries: Toward a de-commercialisation of the commons’, Progressive Librarian, 24, 85-114

Wilburn, Thomas. ‘Libraries are dealing with new demand for books and services during the pandemic’, NPR, 16 June 2020, available at https://www.npr.org/2020/06/16/877651001/libraries-are-dealing-with-new-demand-for-books-and-services-during-the-pandemic, accessed 20 October 2020

Wu, M. M. (2019), ‘Revisiting controlled digital lending post-redigi’, First Monday, 24 (5), available at https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v24i5.9644, accessed 12 January 2021

Zeidler, M. (2020), ‘Libraries welcome temporary e-book pricing, licensing changes from publishers’, CBC News, 6 June 2020, available at https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/libraries-e-books-1.5600613, accessed 21 October 202

eBook licensing: Libraries pay publishing companies for licences that allow them to hold and lend eBooks under certain conditions as dictated by the publisher. This is in contrast to purchasing ownership of a book, in which case the owner may do what they like with the book.

Restrictive licensing: Publishing companies impose certain restrictions on what the library or the reader may do with the eBook; for instance, readers are typically prevented from copying the text, saving the file to their device, or sharing the file. Restrictions for libraries may include an upper limit on how many times the eBook may be lent to readers before the licence expires and must be repurchased, or a length of time before the licence expires, or both.

Internet Archive: An archiving organisation based in the USA that, among other things, digitises physical works for the purpose of preservation. These digitised works are made available for free access to online patrons via the Open Library. Their major focus is on digitising historic works, which are in the public domain; however, more recent publications are also collected.

Fair Use: An ‘exception’ of sorts to copyright law. Copyright law prohibits copying or reproducing of works for a certain period of time after its first publication. Fair Use applies in certain circumstances, usually for criticism, commentary or mockery of a copyrighted work.

To cite this paper please use the following details: Yesberg, H.J. (2022), 'Libraries, Piracy and the Grey Area In-Between: Free Digital Media during the COVID-19 Pandemic', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 15, Issue 1, https://reinventionjournal.org/article/view/799. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.