Gervaise Alexis Savvias, University of Warwick

[The] struggle for liberation has significance only if it takes place within a feminist movement that has as its fundamental goal the liberation of all people.

(hooks, 1981: 13)

In the words of Audrey Lorde, ‘there is no such thing as a single-issue life’ (Black Past, 2012). Radical Black feminist literature has discussed the legal or otherwise non-legal disadvantages of living multiple-issue lives. Discrimination can no longer be considered from a single-axis view. Intersectionality, as a key concept, appreciates and discusses the very intersecting axes of discrimination. This contribution would argue that the contemporary rule of law, and otherwise non-legal structures, still fail to adequately recognise an intersectional approach. In so failing to apply the theorem in a systemic approach, there has been an obstruction of the encasement and appreciation of a diverse world population. This article addresses the growing lacuna of society in moving towards true freedom and equality.

Keywords: Black feminism, intersection of identities, intersectionality in multiple frameworks, limitations of legal analysis, radical Black feminist ideologies

Although a key tool of analysis (Mattsson, 2014) in academic feminism and legal discussion, it has become patently evident that contemporary legal and non-legal frameworks manifestly fail to recognise and subsequently apply an intersectional approach. Through this article, I aim to assess, understand, and discuss Kimberlé Crenshaw’s intended assertion found through her paper: ‘Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex’ (Crenshaw, 1989). Crenshaw (re)introduces and critically contemplates the modern distortion of Black women, either due to the (continued) emergence of white feminism or a misunderstanding of the foundational importance of intersectionality. An epistemic approach demonstrates that Western nations continue to be plagued by emphatic racial and gendered injustices. While Crenshaw’s decompartmentalisation of intersectionality pertains to the United States of America, this article – if not a legalised analysis – aims to address that, as a standalone idea, intersectionality is microcosmic in nature as some academics have suggested (Williams, 2009: 93), with relevant paradigms to reiterate this view.

Crenshaw’s article (1989) has reignited academic (or otherwise) thought around the importance of considering the multiplicities in our livelihood, due to frameworks that seek to compartmentalise, if not individualise, us. Her discussion is a useful (starting) point in the furthered exploration of critical race theory and Black feminism. To effectively address and discuss her ideas, there must initially be a discussion of what intersectionality, in and of itself means. From the offset, Crenshaw establishes herself as a contemporary of existing Black feminist theory, outlining that there is often a ‘tendency to treat race and gender as mutually exclusive categories of experience and analysis’ (Crenshaw, 1989: 139). Audre Lorde, a quintessential Black feminist, outlined that there is ‘no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives’ (Black Past, 2012). Echoing these very same sentiments in a USA that was in the midst of its post-enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Crenshaw aims to shine a light on what it means to be not only Black, but also a woman, and what this intersection of distinct identities realistically means. Reiterating Lorde’s sentiments, Crenshaw insists that a focus on ‘singular issues’, especially through a single-axis analysis, manifestly fails to recognise and leads to the marginalisation and isolation of ‘those who are multiply burdened’ (Crenshaw, 1989: 140). Furthermore, considering Crenshaw’s concepts more intrinsically, she makes a distinct clarification in which she outlines how traditional (if not first wave) feminist theory has ‘created a distorted analysis of race and sex’ (Crenshaw, 1989: 140) solely on the basis of compartmentalising ‘Black men and all women’ or ‘Blacks and white women’. (Crenshaw, 1989: 140) This conscious distinction proliferated by a system of racial capitalism (Robinson, 1983), in vitro our socio-economic frameworks, has barred a basic comprehension that (more often than not) these elements coincide organically. This contribution would argue that various structures of the law, education, healthcare, and so on consciously ignore this organic coinciding. Perhaps more important to note is the inherent individualisation of the ordinary person in our current system and metrics. Capitalism individualises all of us (Bromley, 2019) – specifically those that are relegated to the margins of society. White feminism operates through the lens of individualised lifestyle choices and discourse. Women are incessantly reminded of the need to be resilient, and operate with a (n unending) positive attitude in order to deal with a long history of inequalities – but I argue that this is simply not enough. An acute distance is established if we follow this train of thought – for the betterment of all cannot come with the acute dismantling of systems, which sees each of us pushed into the periphery due to our multiplicities. Important to note, in due continuation, is the basis for much of Crenshaw’s paper: the struggle of Black women, especially with regards to feminist theory, critical race theory and political discourse.

Crenshaw outlines the marginalisation of Black women in various areas of life, with a larger discussion on what Asafa Jalata refers to as ‘the Black Struggle’ (Jalata, 2002). The Black liberation movement found in vitro of the Civil Rights Movement effectively and ‘legally dismantled institutional racism [but] it failed to eliminate indirect institutional racism’ (Jalata, 2002: 86). Crenshaw’s considerations concur with the propositions Jalata has introduced. The ‘problems of exclusion cannot be solved by simply including Black [women or men] within an already established […] structure’ (Crenshaw, 1989: 140). In the eyes of academia, Crenshaw’s thoughts serve as a fascinating tool. For contextualisation, Crenshaw’s analogy of discrimination is akin to that of traffic in an intersection flowing in ‘all four directions’ (Crenshaw, 1989: 149). The metaphorical reference is insightful as well as comprehensible. For the sake of her analogy, if an accident were to occur, it cannot only occur from traffic oncoming from one direction, but perhaps from all or, at least, various directions. In a similar way, discrimination must be considered from more than just a single-axis system or approach. Discrimination remains multi-faceted. If not for the aforementioned reasons, then because ‘any analysis that does not take intersectionality into account cannot sufficiently address the particular manner in which [Black women or men] are subordinated’ (Crenshaw, 1989: 140).

Undoubtedly, a modern reception of Crenshaw’s ideas cogitates that marginalisation is rife in a disproportionate majority of communities around the world. While critics have challenged Crenshaw’s proliferation of intersectionality as an effort to thwart and invert the progress of our collective betterment in a contemporary world, this argument, alongside Crenshaw herself, would refute this debasement of her theory. Rather, the basis of intersectionality is to ‘make room for more advocacy and remedial practices’ (Coaston, 2019). To truly enact change is to introduce collective thinking, governance and systems that encourage nothing but egalitarianism. In continuation, this article takes on an epistemic approach in order to address the lack of attention intersectionality as a theorem receives when white feminism makes (obtuse) use of the term, and the subsequent impact this has on the systemic marginalisation of non-white bodies. (Frankenberg, 1993: 51–84) These pertinent examples are taken from Crenshaw’s original paper, as well as various twenty-first century implications of the failure of (legal, or otherwise non-legal) structures and entities in adequately recognising the intersection of various characteristics. This conscious dismissal has left a plethora of non-white bodies relegated to the sidelines of society.

In the case of DeGraffenreid v General Motors Assembly Div, a suit was brought forwards against General Motors. The five plaintiffs, all Black women, argued that the employment seniority system ‘perpetuated past discrimination against Black women’. Due to the fact that the suit was not brought on behalf of just ‘women’ or ‘Blacks’, having considered these ‘characteristics’ as ‘singular issues’, but instead on behalf of Black women, the court was ardent in its ruling. It stated:

[The plaintiffs] should not be allowed to combine statutory remedies to create a new ‘super-remedy’. […] Thus, this lawsuit must be examined to see if it states a cause of action for race discrimination, sex discrimination, or alternatively either, but not a combination of both.

Similarly, Moore v Hughes Helicopter Inc. presents a canonically similar marginalisation of Black women. It illuminates how courts, in Crenshaw’s words, ‘fail to understand or recognise Black women’s claims’.

It comes as no surprise that Malcolm X also once stated that ‘the most unprotected woman in America is the Black woman’ (Malcolm X, 1962). On a differing note, there is particular issue to be had with the idea of ‘whiteness’ as an overhead concept. In Moore v. Hughes Helicopters, Inc., the court outlined that ‘Moore has never claimed […] that she was discriminated against as a female, but only as a Black female’ (Moore v. Hughes Helicopters, Inc: at 480). In essence, the court raised the question as to how the complaints brought through via the suit itself were ‘adequately represent[ative] of white female employees’ (Moore v. Hughes Helicopters, Inc: at 480), highlighting the failure to embrace intersectionality as a form of analysis while simultaneously contouring and proliferating racist undertones. Instead, the Ninth Circuit centralised white female experiences as the groundwork for gender discrimination on the whole, consolidating the narrow scope of the law to accredit and make note of marginalised peoples: a phenomenon still seen in a modern-day setting.

Furthermore, Crenshaw goes on to argue that Moore remains a representative illustration and prime example of ‘the limitations of antidiscrimination law’s […] normative vision’ (Crenshaw, 1989: 145). In line with this argument, Crenshaw continues to expand on what much of her paper aims to address and tackle: a conscious refusal stemming from a system of law in recognising a multiple-disadvantaged class of people, such as Black women. Essentially, this refusal defeats the overhead effort to sincerely restructure an already established hierarchy that places privileged classes, such as white women, on the top in civil lawsuits. The court would not entertain the possibility that discrimination faced by Black women could also be combined, per se, with sex discrimination, manifestly dismissing the notion and reality of intersectionality.

In 1851, Sojourner Truth declared ‘Ain’t I a Woman?’, directly challenging the sexist imagery imposed and introduced by white males at a Women’s Rights Conference in Akron, Ohio, who deemed women weak in attempting to permeate the responsibilities of political activity and inclusion. Even in the midst of startling urgency to silence Truth emerging from surrounding white women, she recounted her experiences as a Black woman during the horrors of slavery:

Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted and gathered into barns, and no man could head me, and ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man, when I could get it, and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have born thirteen children, and seen most of ’em sold into slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me, and ain’t I a woman?

As aforementioned, Crenshaw predominantly, if not entirely, focuses on the experiences of Black women in her paper. On enacting her critique of various frameworks that manifestly fail at recognising the intersection of various identities that make up an individual, she glaringly critiques white feminism at its core: what it has achieved, or lack thereof, for women on a wider scale. Whiteness, in of itself, can be – and has been – considered hegemonic (Hughey, 2010). Amos and Parmar’s argument that white feminism’s concern over ‘short term gains such as equal opportunities and job sharing’ (Amos and Parmar, 1984) aptly and succinctly illustrates how the goals of white feminism have clouded true, long-lasting progress. As Françoise Vergès has argued, ‘capitalism has no hesitation in taking up corporate feminism’ as the inequality perpetuated by legal and non-legal frameworks has become a larger question based around ‘mindset or lack of education rather than of oppressive structures’ (Vergès, 2021). Using the election of Margaret Thatcher as a key example – where a conscious acceptance of her virtues and morals are lauded under the guise of a strong female leader – Amos and Parmar argue that these very virtues continue to ‘further alienate Black women whose experience at the hands of the British state demands a more responsible political response’ (Amos and Parmar, 1984: 4). Gender in relation to class and race cannot be separated. The ‘cultural and racial myopia of white feminism’ (Amos and Parmar, 1984: 5) that imagines women as universal is inherently flawed, ultimately having led to misconceptions of gender relations. Black feminists, such as Crenshaw and Lorde, consistently and artistically defend this notion.

In exporting the theory of intersectionality and considering it from a globalised point of view, contemporary examples can be found in all corners of the world. The intersections of discrimination remain a phenomenon that an international world has manifested through no effort of its own. Methodically, in a manner akin to Crenshaw, this article continues in employing and exploring other present-day examples with the end goal of further illustrating a series of methodical failures in apt implementation of an intersectional approach. The next critical juncture which this article turns to aims to comment on and analyse the matrix framework of intersectionality within the UK. That there is still issue with the ways the concept translates and interacts with the law cannot be ignored. The category of provisions of discrimination law is exhaustive and enumerated in the UK.[1] In light of political and social campaigns for the introduction of various anti-discrimination doctrines and policies, this phenomenon cannot be considered in isolation. Nonetheless, the introduction of anti-discrimination law was inevitable as much as it can be analysed as worthwhile. In lieu of Acts enacted by Parliament to remedy the issues of a non-intersectional approach, there remain fundamental issues perpetuated by the courts that stagnate and stunt advances in a legal environment.

Taking, for example, the Equality Act 2010 (‘EA 2010’), there is a particular issue to be had with regards to UK legislation on the protection of worker’s rights and its continued interaction with a theory such as intersectionality. Under the EA 2010, ‘a protected characteristic’ (Equality Act, 2010: Pt. 2, Chapter 1; emphasis added) can include race, sexual orientation and religion, (Equality Act, 2010: Pt. 2, Ss 4–12) to name a few. While Section 14 outlines provision to address direct discrimination on ‘a combination of two relevant protected characteristics’ (Equality Act, 2010: S.14.1), it has never been brought into effect. Instead, government has deemed it too ‘complicated and burdensome for business’ (Wren, 2018). Furthermore, while the section considers a combination as aforementioned, it can be argued that the reduction to only ‘two relevant characteristics’ (Equality Act, 2010: S.14.1) by nature of ‘dual discrimination’ is lacklustre in and of itself. While identifiable individualities are important to note, it cannot be denied that socio-economic considerations must also be made in a holistic effort to enact equality in civil case law. In retrospect, UK discrimination law takes on a distinct approach; allowance solely for a single characteristic to be considered treats identity characteristics as ‘discrete, homogenous groups’ (Smith, 2016: 88). While the limitation was introduced, as the Government Equalities Office states, as a modem to alleviate ‘unnecessary complicating’ of the law (Government Equalities Office, 2009: Para. 4.6), this does not seem entirely convincing. Although it may be harder for ‘a claimant to provide evidence of [intersectional discrimination], it does not translate into complexity for a court’ (Smith, 2016).

Turning to UK case law, while there is evidence that lower tribunals are considerate of claims that raise intersectional discrimination, they are far and wide apart. In the case of Nwoke v Government Legal Service, there exists indicatory endorsement of additive discrimination: categorised as ‘discrimination occurring in relation to more than one ground’ (Solanke, 2009: 728). The claimant, a Nigerian-born woman, found herself in the application process for a job with the Government Legal Service. On further examination of the rankings by the court, it became apparent that the claimant had the lowest ranking out of all her peers, regardless of race. All white applicants, regardless of gender, ultimately ranked higher than her, even in the case that they had lower degree classifications. As such, Ms Nwoke successfully alleged that she suffered double or additive discrimination. The tribunal found that the single identifiable factor that ranked Ms Nwoke so low on the ranking scale was her race and, therefore, there was unlawful racial discrimination at play. Furthermore, it was also found that white women were not only less likely to be hired in comparison to men, but in the case that they were hired, they were paid lower salaries, too. On this illustrative evidence, the tribunal also found discrimination based on sex, placing women at a disadvantage when compared to men (Solanke, 2009: 428). The claimant had proved that both facets of discrimination were not independent of each other, but instead, she was subject to discrimination because she was Black and she was a woman. In lieu of this, emphatic opposition can be observed in the higher courts within the UK, such as the Court of Appeal (‘CA’). In the case of Bahl v Law Society, Ms Bahl resigned her high-ranking position within the Society on account of ‘race and sex discrimination’ (Bahl v Law Society, 2004: para. 4). Ms. Bahl lost her case in the CA, with Peter Gibson LJ holding that:

it is not open to a tribunal to find either claim [race or sex discrimination] satisfied on the basis that there is nonetheless discrimination on grounds of race or sex when both are taken together.

UK courts have been shown to be confined by legislation, by no fault of their own. ‘Discrimination is confined to the single-axis mode’ (Smith, 2016: 91), reiterating Crenshaw’s attitudes, and a systemic failure to consciously enact intersectional approaches leaves many civil cases at the behest of bigotry and non-representative policy. Once again, those that find themselves already on the periphery are pushed to the margins of livelihood.

Non-legal frameworks of society have been shown to be dismissive of intersectionality and its intricately entwined function. Statistics have shown that non-white women experience differential (if not inhumane) treatment in various sectors of healthcare – a key framework that impacts a society’s collective livelihood. A key example can be found in the USA after the tragedy of 11 September 2001 (‘September 11’, or ‘9/11’). It has often been discussed, through statistical data (Cainkar, 2009), that persons perceived to be of Arab descent experienced an increase in harassment, violence and ill workplace treatment in the months and years following September 11 (Lauderdale, 2006). Through her investigation, Diane Lauderdale directly analyses the State of California’s relative risk of poor birth outcome in comparison to an exact calendar year following the events of 9/11. Concurring with social epidemiologists who have studied the effects of racial or ethnic discrimination on health consequences and complications (Williams et al., 2003), her data reflects a startling reality: ‘ethnicity-related stress or discrimination during pregnancy increases the risk of preterm birth or low birth weight’ (Lauderdale, 2006: 197). An entire ethnic community, Arab and Muslim Americans, were subject to a barrage of extreme bigotry. While Lauderdale’s results support her hypothesis, they underpin an irrefutably saddening aspect. The misgivings of an already underfunded and troubled healthcare system, fuelled by prejudiced undertones, essentially failed to cogitate the effects of multiple facets of discrimination in an already tense environment for Arab and Muslim women.

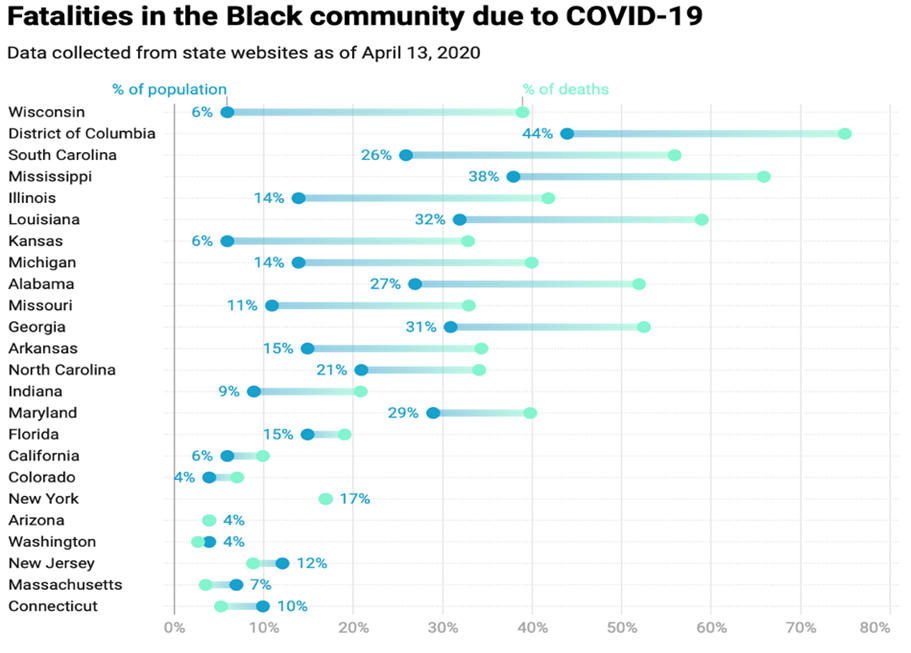

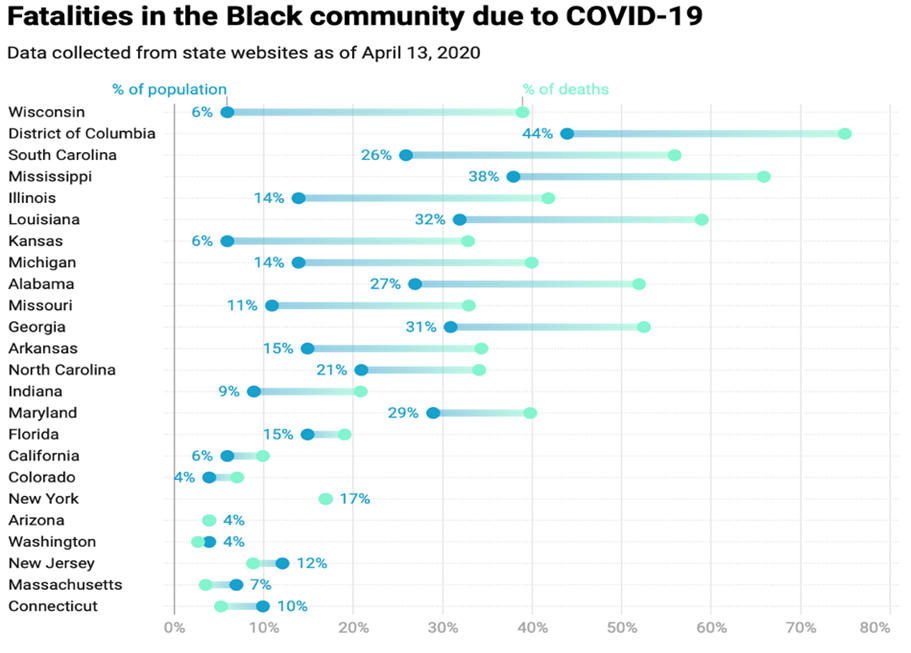

In a categorically similar case, the outbreak of the 2019–20 SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has infected and killed Black people in the USA and the UK at excessively high rates. In the case of the former, the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (‘the CDC’) has gathered state-wide figures that emphasise a depressive reality: ‘Black people overall have disproportionately contracted and (emphasis added) died from the coronavirus’ (Rios and Rangarajan, 2020). To illustrate this phenomenon, the cultivation of the following graph (Figure 1) depicts how the state of the current public healthcare system emphasises ‘entrenched inequalities in resources, health and access to care’ (Eligon et al. 2020).

In the case of the latter, the UK has equally reported chilling statistics around the death of Black British people due to the pandemic. The Office for Statistics (2021) has highlighted the inherent danger of the (ongoing) pandemic on non-white bodies. The list of possible reasons for the unprecedented death toll for non-white bodies is long, as there is no one cause for the racial disparities. (Laveist et al., 2011) Black people are more likely (Gamio, 2020) to work jobs that are considered essential – such as grocers, cleaners, transit workers – putting them at a direct risk of infection and, more morbidly, death. Clyde Yancy insists that ‘a 6-fold increase in the rate of death for African Americans due to a now ubiquitous virus should be deemed unconscionable’ (Yancy, 2020), as well as an indication that a post-racial world is simply a myopic distortion of the realities that we continue to face. While the deadly impact of the virus has subsided due to remarkable breakthroughs in vaccine technology, ‘health care disparities will persist’ (Yancy, 2020: 2). The systemic failures of public healthcare, such as the aforementioned, are simply microcosmic examples of the ineptitude to interact with intersectionality on a wider scope and truly account for the intersection of multiple identities, and how to subsequently deal with these multiple identities on a basis of wanting to see the betterment of us all.

In conclusion, when we ‘fail to acknowledge [intersections of discrimination], much less address these issues, we are failing at diversity’ (Pao, 2016). When applied steadfastly, such as through policy considerations, intersectionality recognises the complexities in an individual’s identity – an occurrence that might not otherwise be accessible through a single-axis method or a one minority marker system. This article has aimed at depicting that intersectionality as a framework, while emerging from a primary legal analysis, also extends to various other socio-economic aspects of our livelihood. An initial analysis of case law in both the USA and the UK depicts a chilling image: a denial by the courts to recognise inextricable entwinement of our various (sociological) identities. In tandem to this, this contribution has articulated that the lack of an intersectional approach is not an isolated phenomenon restricted to the legal stratosphere: it is an extensive, conscious and ubiquitous denial to cogitate the multiplicities in our identities within (virtually) all systems in which we (co)exist. To that end, this contribution would note that as a collective (populace), we can no longer rely on mechanisms and systems that are not built to house an increasingly diverse world population. The interplay, if not mixing, of identities has illustrated the gravitational effect this can have on one’s livelihood. If systems slowly begin incorporating an intersectional approach, the world comes one step closer to a modem of egalitarianism, akin to what a plethora of Black feminists (or otherwise marginalised peoples and theorists) originally envisioned. On average, intersectionality provides an acute insight as to how the promotion of diversity can ‘prevent and remedy inequalities’ (Truscan and Bourke-Martignoni, 2016: 131), with a holistic end goal of ‘identifying, addressing, and reinforcing universal […] human rights guarantee’ (Truscan and Bourke-Martignoni: 131). By recognising intersectional discrimination, and continuing to do so, we can truly make progress on achieving meaningful and substantial equality. Or, as Crenshaw puts it: ‘When they enter, we all enter’ (Crenshaw, 1989: 167; emphasis added).

Figure 1: Figure 1: Fatalities in the Black community due to COVID-19 (Rios, E. and S. Rangarajan (2020). Reprinted with permission from Mother Jones, copyright (2020) Mother Jones).

Amos, V. and P. Parmar, (1984), ‘Challenging imperial feminism’, Feminist Review, 17, 3–19.

Bromley, D. W. (2020), Possessive Individualism: A Crisis of Capitalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cainkar, A. L. (2009), Homeland Insecurity: The Arab American and Muslim American Experience After 9/11: New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Coaston, J. (2019) ‘The intersectionality wars’, Vox, available at https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/2019/5/20/18542843/intersectionality-conservatism-law-race-gender-discrimination, accessed 22 October 2020.

Crenshaw, K. (1989), ‘Demarginalizing the intersections of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics’, University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1 (8), 139–67.

Eligon, J, D. S. A. Burch, D. Searcey and A. R. Oppel Jr., ‘Black Americans face alarming rates of coronavirus in some states’, New York Times, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/07/us/coronavirus-race.html, accessed 23 April 2020;

Flexner, E. (1975), Century of Struggle: The Women’s Rights Movement in the United States, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Frankenberg, R. (1993), ‘Growing up White: Feminism, racism and the social geography of childhood’, Feminist Review, 44 (1), 51–84.

Gamio, L. (2020), ‘The workers who face the greatest coronavirus risk’, New York Times, available at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/15/business/economy/coronavirus-worker- risk.html, accessed 24 April 2020;

hooks, b. (1981), Ain’t I A Woman: Black Women and Feminism: Boston, MA: South End Press.

Hughey, W. M. (2010), ‘The (dis)similarities of white racial identities: The conceptual framework of ‘hegemonic whiteness’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 33 (8), 1289–1309.

Jalata, A. (2002), ‘Revisiting the Black struggle: Lessons for the 21st century’, Journal of Black Studies, 33 (1), 86–116.

Lauderdale, S. D. (2006), Birth outcomes for Arabic-named women in california before and after September 11’, Demography, 43 (1), 185–201.

LaVeist, T., K. Pollock, R. Thorpe Jr., R. Fesahazion and D. Gaskin (2011), ‘Place, not race: Disparities dissipate in southwest Baltimore when Blacks and Whites live under similar conditions’, Health Affiliation (Millwood), 30 (10), 1880–07;

Black Past (2012), ‘(1982) Audre Lorde, “Learning from the 60’s”’, available at https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1982-audre-lorde-learning-60s/, accessed 25 October 2020,

Mattsson, T. (2014), ‘Intersectionality as a useful tool: Anti-oppressive social work and critical reflection’, Afilia: Journal of Women & Social Work, 29 (1), 8–17.

Office for Statistics (United Kingdom), ‘Coronavirus and the social impacts on Great Britain: 1 April 2022’, available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/bulletins/coronavirusandthesocialimpactsongreatbritain/1april2022, accessed 2 April 2020.

Pao, K. E., ‘True diversity is intersectional’, Project Include, available at https://medium.com/projectinclude/true-diversity-is-intersectional-2282b8da8882, accessed 23 October 2020.

Rios, E. and S. Rangarajan (2020), ‘COVID has infected and killed black people at alarming rates. This data proves it’, Mother Jones, available at https://www.motherjones.com/coronavirus-updates/2020/04/covid-19-has-infected-and-killed-black-people-at-alarming-rates-this-data-proves-it/, accessed 21 April 2020,

Robinson, C. J. (1983), Black Marxism: Making of the Black Radical Tradition. London: Zed.

Smith, B. (2016), ‘Intersectional discrimination and substantive equality: A comparative and theoretical perspective’, Equal Rights Review, 16, 73-102.

Solanke, I. (2009), ‘Putting race and gender together: A new approach to intersectionality’, Modern Law Review, 72 (5), 723–49.

The Government Equalities Office (2009), Equality Bill: Assessing the Impact of a Multiple Discrimination Provision, Para 4.6–4.7.

Truscan I. and J. Bourke-Martignoni (2016), ‘International Human Rights Law and Intersectional Discrimination’, The Equal Rights Review, 16, 103–31.

Vergès, F. (2021), A Decolonial Feminism: London: Pluto Press.

Williams, L. R. (2009), ‘Developmental issues as a component of intersectionality: Defining the smart-girl program’, Race, Gender & Class, 16 (1/2), 82–101.

Williams, R. D., W. H. Neighbors and S. J. Jackson (2003) ‘Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies’, American Journal of Public Health, 93 (2), 200–08.

Wren A. (2018), ‘Intersectionality: What is it and why does it matter?’, Farrer, available at https://www.farrer.co.uk/news-and-insights/blogs/intersectionality-what-is-it-and-why-does-it-matter-for-employers/, accessed 24 April 2020,

Yancy W. C. (2020), ‘COVID-19 and African Americans’, Jama, 323 (19), 1891–92.

Case law

Bahl v Law Society [2004] EWCA Civ 1070;

Nwoke v Government Legal Service and Civil Service Commissioners [1996] IT/43021/94.

Degraffenreid v. General Motors Assembly Div., Etc., 413 F. Supp. 142 E.D. Mo. 1976.

Moore v. Hughes Helicopters, Inc., 708 F.2d 475 United States, 9th Cir. (1983).

Statutory law(s)

Equality Act 2010.

Civil Rights Act 1964.

Black Feminist theory: A philosophical approach that centres on the experiences of Black women and their relation to feminism. This lens emerged out of critiques that mainstream feminism does not acutely analyse the interaction of white supremacy and the patriarchy.

Critical race theory: A interdisciplinary intellectual and social approach which seeks to examine the intersections of race, gender, sexuality, society and law in academic (or otherwise) analyses.

Egalitarianism: The doctrine that all people (regardless of manufactured differentiating factors) deserve equal rights, opportunities and freedom to live as autonomous individuals.

Intersectional approach: Sociolegal analysis encompassing the analysis of gender, class and race.

Marginalisation: The treatment of a person, group as peripheral. In the context of this body of work, the process of marginalisation is institutionalised and actioned by the State apparatus.

Single-axis analysis: A single-axis analysis treats race and gender as mutually exclusive categories of experience, rather than their inherent symbiotism.

To cite this paper please use the following details: Savvias, G.A. (2022), 'Comments on Intersectionality', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 15, Issue 1, https://reinventionjournal.org/article/view/758. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.