Kida Lin[1], School of Philosophy, The Australian National University

We commonly think that promising creates reason for us to act. If I promise to have lunch with you, there will then be reason in favour of me doing so, and there will also be reason against me doing anything else. But this seemingly plausible view generates a puzzle: if making a promise gives us reason to do something, moral agents can sometimes promise to fulfil a less weighty obligation, and thereby ensure that they will do all they ought to do by fulfilling this obligation. Call this the puzzle of suboptimal promises. In this paper, I examine and reject two proposals for responding to this puzzle, before presenting my own solution. I argue that we should conceptualise promising with reference to what Joshua Gert calls the 'justifying/requiring strength' of reason. In particular, when an agent S promises to do something, the requiring strength of doing that thing increases in virtue of the promise.

Keywords: Promising, justifying strength, requiring strength, two dimensions of reason, Holly Smith, Earl Conee.

We commonly think that promising creates reason for us to act. If I promise to have lunch with you, there will then be reason in favour of me doing so, and there will also be reason against me doing anything else. Let us use the term 'deontic value' to represent 'the force of the moral reasons to perform or not perform [an] act' (Smith and Black, forthcoming: 10–11). It seems that we are committed to the following:

This seemingly plausible view, however, leads to the following puzzle.

NEPOTISM: Dean Baker can fund just one adjunct faculty position. Baker knows that if she assigns the position to the Classics department, they will conduct a fair search and hire Baker's cousin, the best available candidate. Baker also knows that History is the one department with a considerably greater need for an adjunct than that of Classics. It just so happens that although Baker can promise the position to Classics, she cannot promise it to History. Suppose, say, she has no way to communicate with the History department at the time. She can, however, allocate the funds to either department. Wanting her cousin to have the job, Baker promises the position to Classics and later keeps that promise.

The problem is this: if making a promise gives us reason to do something, moral agents can sometimes promise to fulfil a less weighty obligation, and thereby ensure that they will do all they ought to do by fulfilling this obligation. Call this the puzzle of suboptimal promises (Smith, 1997; Smith and Black, forthcoming). When I say an obligation is 'less weighty', I just mean there is less reason to do it independent of consideration about the promise. In addition, I use 'obligation' to refer to things that moral agents have relatively stringent pro tanto reason to do (Reisner, 2013). In NEPOTISM, giving funds to Classics is a less weighty obligation in the sense that it is something Baker has less pro tanto reason to do.

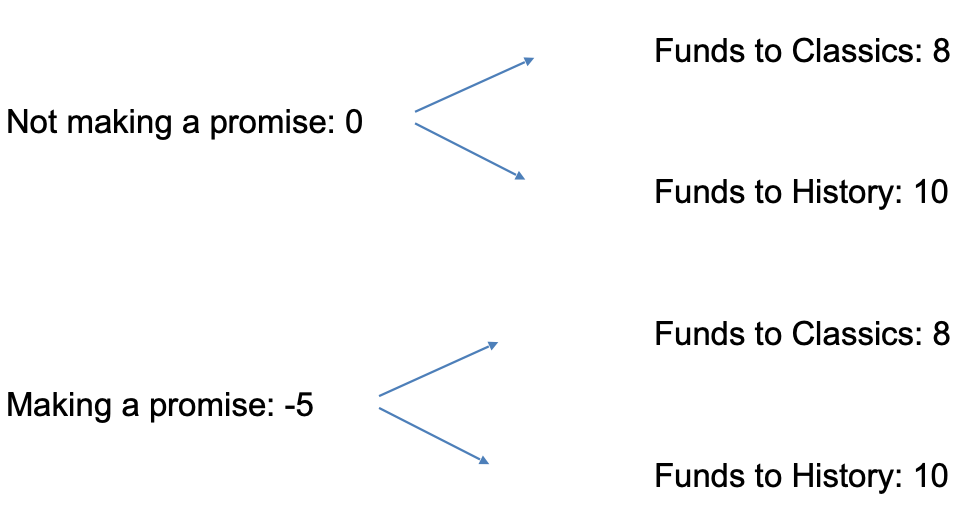

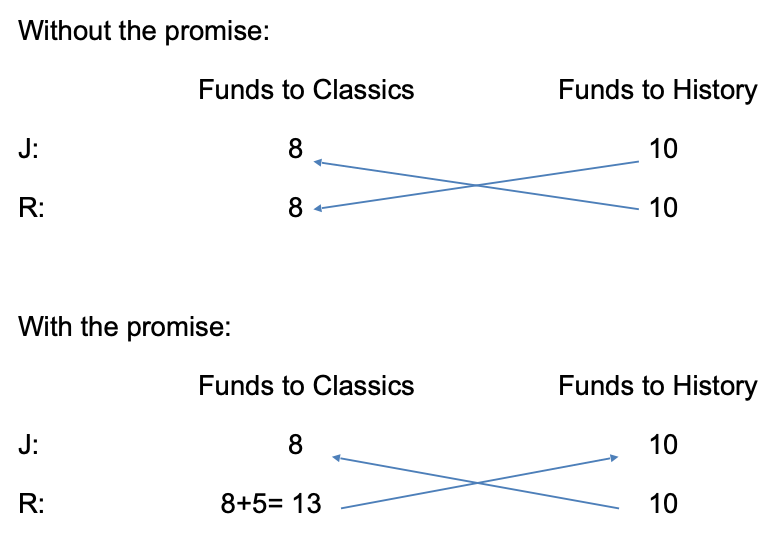

To illustrate the puzzle, suppose that allocating the funds to Classics and History department has a deontic value of +8 and +10, respectively. Suppose also that the deontic value of keeping a promise and breaking one is +5 and -5. Baker seems able to make allocating the funds to Classics part of what she ought to do by making a promise:

If Baker does not promise Classics the funds, the deontic value of her options:

Funds to Classics: 8

Funds to History: 10

If Baker does make the promise, the deontic value of her options:

Funds to Classics: 8+5=13

Funds to History: 10-5=5

Among her available options {funds to Classics; funds to History; promise and funds to Classics; promise and funds to History}, what Baker has the most reason to do now becomes making the promise to Classics and following it through. It seems strange that Baker can render benefitting her cousin what she ought to do merely by making a promise.

Before proceeding, four clarificatory remarks are in order here. Firstly, we should distinguish the puzzle of suboptimal promises from what some philosophers call the problem of wicked promises (Thomson, 1990; Foot, 2002; Watson, 2009; Shiffrin, 2011; Owens, 2016). The problem of wicked promises concerns cases where the agent promises to do demonstrably immoral acts such as stealing and killing. The question there is whether the agent has any more reason to steal or kill in virtue of having made the promise. Though both having to do with promises to do what is impermissible, the paradox of suboptimal promises differs in that it does not concern acts that are pro tanto impermissible such as stealing and killing. Instead, it focuses on acts that are pro tanto permissible but impermissible all-things-considered (e.g., allocating funds to Classics) (see Reisner, 2013).

Secondly, the puzzle of suboptimal promises is not a puzzle about whether the agent ought to keep a promise she should not have made in the first place. This latter issue, which we might call the question of wrongful promises, concerns what you ought to do after you have made a wrongful promise. In NEPOTISM, it is plausible that Baker ought not to keep her promise, as she should not have made it in the first place. So, it is plausible that Baker should allocate the funds to History even after she promised it to Classics, and it is tempting to think that the Conventional View suggests otherwise (as the deontic value of funds to Classics and History is 13 and 5, respectively). This, however, would be a mistake (cf. Conee, 2000: 412–14). The Conventional View is perfectly capable of accommodating the fact that sometimes wrongful promises ought not to be kept. This can be done by ascribing different numerical value to available courses of action. For example, if we ascribe +0.5 and -0.5 to keeping and breaking a promise, we would have the result that Baker ought to allocate the funds to History despite her promise to Classics:

If Baker does not promise Classics the funds:

Funds to Classics: 8

Funds to History: 10

If Baker does make the promise:

Funds to Classics: 8+0.5=8.5

Funds to History: 10-0.5=9.5

That is to say, the puzzle of suboptimal promises concerns whether a moral agent can manipulate her normative situation in such a way that she does all she ought to do by promising to do something and later fulfilling that promise. The unit of evaluation here is the whole sequence of making and keeping a promise. The question of wrongful promises, on the other hand, concerns what a moral agent ought to do after she made a promise she should not have made in the first place. The unit of evaluation here is the act of whether to keep a promise. As we have seen, only the puzzle of suboptimal promises poses a problem for the Conventional View.[2]

Thirdly, I said it is counterintuitive that 'moral agents can sometimes promise to fulfil a less weighty obligation, and thereby ensure that they will do all they ought to do by fulfilling this obligation'. This claim needs to be qualified. It is only counterintuitive in cases where no external consequences are brought about as a result. That is, there are plausible cases where moral agents promise to fulfil a less weighty obligation and make it the case that they do all they ought to do by fulfilling this obligation, given that making the promise gives rise to other positive consequences (Smith, 1997: 153–54; Smith and Black, forthcoming: 25–26). Consider:

RECRUITMENT: Dean Allen is conducting an outside search for a new chair of the Chemistry department. He offers the job to Marilyn Jones, who says she will only accept the position if she has the opportunity to build the department by hiring three new faculty members. Suppose that there is far greater need for new faculty in English and History than in Chemistry, and hence that in circumstances in which no promise had been made, the dean would have been obliged to provide the lines to these two departments rather than to Chemistry. The dean makes a commitment to Jones to provide three new lines to the Chemistry department.

In RECRUITMENT, it can be that Allen has done all he ought to do, even though allocating positions to Chemistry is something he would otherwise have less reason to do. For it may be that the positive consequence of having Jones as the new chair more than compensates for the fact that there is less reason to allocate these positions to Chemistry in the first place. For example, Jones may significantly improve the ranking of the department or she may help secure a substantial amount of research funds. We can represent this as follows:

If Allen does not promise Jones:

Positions to Chemistry: 8

Positions to English or History: 10

If Allen does make the promise:

Positions to Chemistry: 8+3+5=15

Positions to English or History: 10-5=5

Here, we suppose that the positive consequence of having Jones as the new chair increases the deontic value by +3. It now seems that Allen is indeed able to ensure that he does what he ought to do by promising to fulfil a less weighty obligation and keeping the promise, although this is by no means counterintuitive. Therefore, the puzzle of suboptimal promises is only a puzzle for cases like NEPOTISM where no external consequences are at stake. In other words, the problem is that moral agents can sometimes promise to fulfil a less weighty obligation, and thereby ensure that they will do all they ought to do by fulfilling this obligation even in cases where making the promise does not bring about positive consequences. I will exclude any consideration arising from external consequences from my discussion below.

Finally, what is implausible about the puzzle of suboptimal promises is the mere fact that moral agents can sometimes promise to fulfil a less weighty obligation, and thereby ensure that they will do all they ought to do by fulfilling this obligation (again, assume that there are no external consequences). Namely, a plausible view on promising should yield the result that moral agents can never manipulate their normative situations in this way. For it is of course the case that there are some instances where the difference in deontic value between weightier obligations and less weighty ones is so significant that making a new promise cannot compensate for it. But that is irrelevant. A plausible view on promising should not allow for any possibility of such manipulation.[3]

Having clarified the puzzle, this paper will proceed as follows. I will first examine and reject two proposals for responding to the puzzle. I then propose my account of promising which I will call promising as requiring. I aim to not only develop an account that answers to the puzzle, but also provide a plausible rationale for it. Namely, the task is both to find a way to ascribe deontic value that accommodates the puzzle and to develop a plausible rationale to justify that way of accommodation.

Consider first how Holly Smith proposes to deal with the puzzle:

To illustrate with NEPOTISM:

If Baker does not promise Classics the funds:

Funds to Classics: 8

Funds to History: 10

If Baker does make the promise:

Funds to Classics: 8+0 = 8

Funds to History: 10–5 = 5

This gives us the intuitive result. Among {funds to Classics; funds to History; promise and funds to Classics; promise and funds to History}, the best course of action is no longer to make a promise to Classics and then keep that promise. Instead, she ought not to make the promise and allocate the funds directly to History.

Importantly, the Moral Cost View is able to guarantee that moral agents can never manipulate her normative situations in the objectionable way mentioned in NEPOTISM. Here is why. Suppose a moral agent S has two obligations, O1 and O2. Suppose that O2 is weightier than O1. On the Moral Cost View, fulfilling O2 will always be what she has most reason to do. For if she promises to fulfil O1, the deontic value of fulfilling O1 will remain the same while that of fulfilling O2 decreases. If she promises to fulfil O2, the deontic value of fulfilling O2 will remain the same while that of fulfilling O1 decreases. Either way, there is always more reason to fulfil O2 directly.

It seems that the Moral Cost View is able to avoid the puzzle of suboptimal promises. The question now is whether Smith can motivate it with a plausible rationale. She presents the following case:

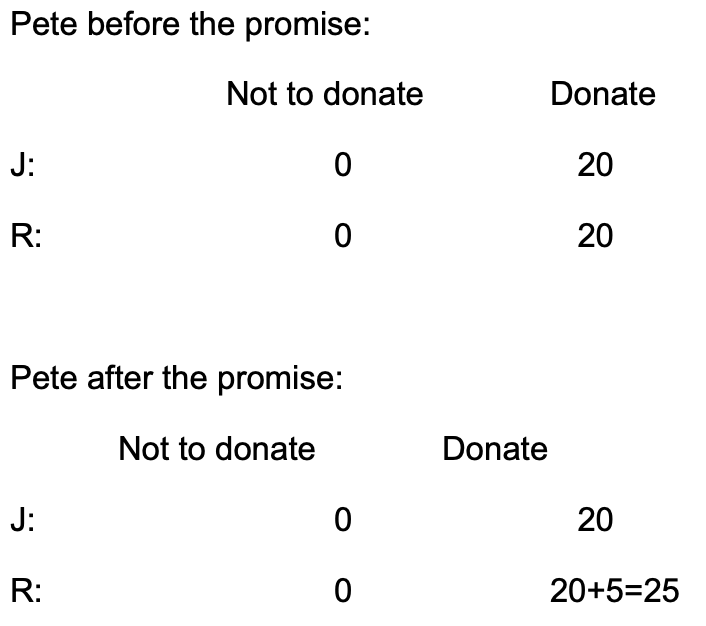

DONATION: Pete and Tom are both asked to pledge a donation. Pete pledges $25 and subsequently donates that amount, while Tom declines to make any pledge, but later donates $25 anyway

Smith points out if we assume the fundraising officials place no reliance on Pete's pledge, so as to preclude external consequences from coming into play, it seems that Pete, as compared to Tom, has not 'performed a morally better or preferable action in donating his $25, simply because Pete is fulfilling a promise' (Smith, 1997: 184–85).

But it is quite unclear how this is supposed to support the Moral Cost View. Smith writes:

Support for [the Moral Cost View] arises from the fact that when we survey an agent's entire course of action from a timeless point of view, we do not ascribe any more moral value to a course of action that involves making and keeping a promise than we do to an otherwise identical course of action that does not involve promising.

By 'moral value', I suppose Smith just refers to the 'deontic value' that we have been focusing on. It then seems that there are two conceptions of deontic value she has in mind. One, which we can call the action-guiding conception, concerns the strength of reason for an action. This is the conception on which we have based our discussion and it has to with what the agent, from an ex ante perspective, ought to do. Under this conception, φ1 has a greater deontic value than φ2 just in case the agent S has more reason to φ1. The other conception of deontic value, which can be called the evaluative conception, has to do with the value of different courses of action assessed from a timeless, ex post perspective. Now, I am not quite sure how to determine the value of a course of action, and Smith is also silent on this question. But here is a plausible view: φ1 has more value than φ2, according to this evaluative conception, just in case a world in which φ1 is performed is better than an otherwise identical world where φ2 is performed. Smith seems to implicitly endorses this interpretation of the evaluative conception in another paper, and it does seem to be a plausible way to assess 'the value of a course of action' at first glance (see Smith and Black, forthcoming: 2–3). For example, all else equal, the world does not seem to become better just by me making and keeping some more promises. But of course, there is still a further question as to how we should understand this 'betterness' relations and what makes one world better than another. Smith does not explicitly address this, and she is content with leaving the assessment of betterness primarily to our intuitive judgements. So, the claim that Pete has not 'performed a morally better or preferable action in donating his $25' derives its plausibility primarily from its intuitive appeal.

Now, in order for DONATION to support her view on promising, it seems that Smith has to commit to the following:

ENTAILMENT A says that a ranking in the evaluative conception of deontic value entails a ranking in the action-guiding conception. Suppose, as it seems plausible, that when Smith talks about deontic value in her Moral Cost View on promising, she is referring to the action-guiding conception. We can then make sense of why DONATION supports the Moral Cost View. DONATION suggests that what Pete has done is not better than what Tom has done, from an evaluative conception. Per ENTAILMENT A, that means Pete does not have more reason to donate his money than Tom does, from an action-guiding conception. Therefore, we should ascribe zero deontic value to keeping a promise.

Notice, however, that there is a distinction between the reason for φ-ing and what we might call the aggregate reason for φ-ing. The reason forφ-ing just depends on the deontic value of φ-ing under the action-guiding conception. More specifically, the reason for φ-ing just depends on the properties that φ has. By contrast, the aggregate reason for φ-ing depends on not only the reason for φ-ing, but also the reason for doing the alternatives of φ. Suppose that an agent can choose from {φ, ψ, ζ}, the aggregate reason for φ-ing depends on the reason for φ-ing as well as the reason for ψ-ing and ζ-ing. In other words, the aggregate reason for φ-ing depends on both the properties ofφ and those of its alternatives. The relevant point here is that ENTAILMENT A applies only to the reason for doing something, and not the aggregate reason for doing it. When I said, 'Pete does not have more reason to donate his money than Tom does', this statement is only true if understood as the reason for Pete's donation and not as the aggregate reason for him doing so. For it is the case that Pete has more aggregate reason to donate his money, as he now has much less reason not to donate.

I think we can now appreciate why Smith's Moral Cost View is an ingenious way of bypassing the puzzle of suboptimal promises. It accommodates the intuitive fact that we ought to keep our promises – namely, that we have more aggregate reason to do what is promised – not by increasing the deontic reason for doing what is promised, but by decreasing the deontic reason for doing what is not promised. This avoids the puzzle of suboptimal promises, as the agent is only able to manipulate her normative situation if she can increase the deontic reason for doing what is promised – in particular, if she can increase the deontic reason for the promised less weighty obligation such that she has more reason to do it than the weightier obligation. It then justifies why assigning zero deontic value to keeping a promise per se is plausible by drawing a link between the action-guiding conception of deontic value and the evaluative conception. There is zero deontic value to keeping a promise, on an action-guiding conception, as the world is not made better by people keeping promises, under an evaluative conception.

For all its merits, I think we should nevertheless reject the Moral Cost View. Consider:

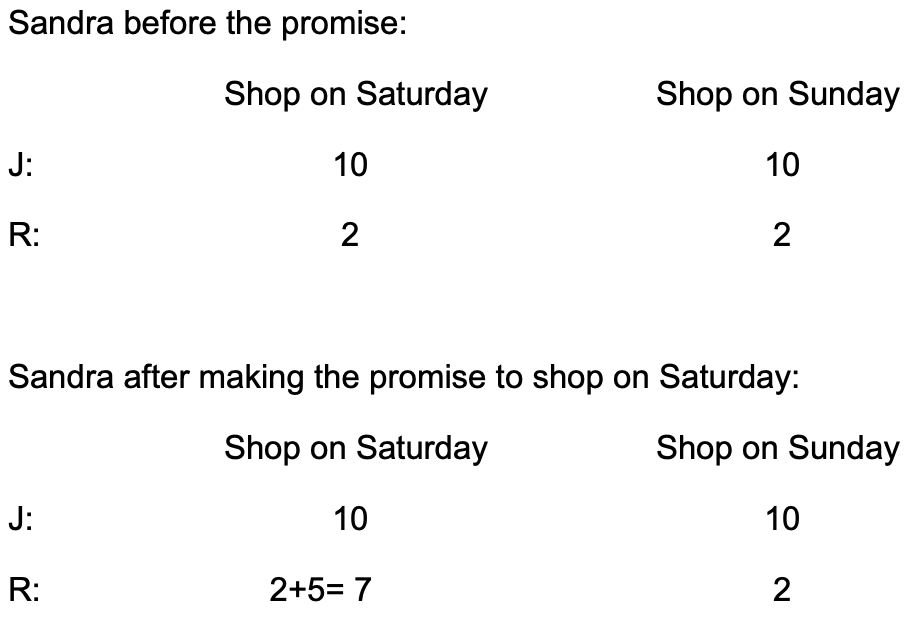

GROCERY ROUTINE: Sandra promises her secretary that she will go to the grocery store on Saturday. However, due to an innocent confusion about which day was promised, she shops on Sunday instead. In addition, this confusion has hardly any impact on Sandra's secretary.

It does not seem that Sandra has done anything worse just in virtue of breaking her promise. This is a problem once we notice that ENTAILMENT A is equivalent to

Per ENTAILMENT A*, there is no less reason to shop on Sunday even though Sandra promised to shop on Saturday. This is in conflict with the Moral Cost View, as it suggests that there is in fact less reason to do what will break a promise. In other words, GROCERY ROUTINE and ENTAILMENT A* lead to the conclusion that we should also assign zero deontic value to breaking a promise. As it turns out, the Moral Cost View does not succeed in sustaining an asymmetry in deontic value between keeping and breaking a promise.

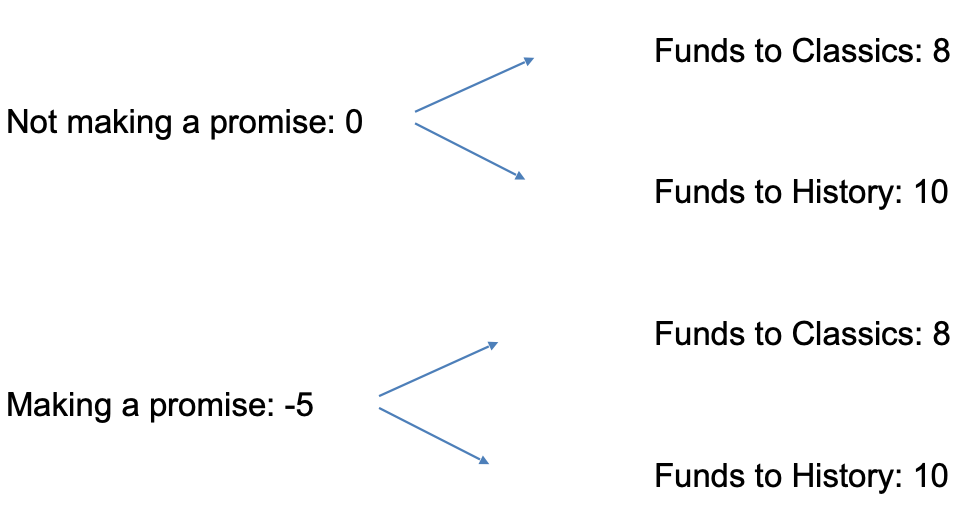

We can also make the same point with NEPOTISM. Its four courses of action are:

If Baker does not promise Classics the funds:

Funds to Classics: 8

Funds to History: 10

If Baker does make the promise:

Funds to Classics: 8 + 0 = 8

Funds to History: 10 - 5 = 5

The problem arises when we compare the act of {funds to History directly} with that of {funds to History} after one promised to allocate it to Classics. It does not seem that the act of allocating the funds to History makes the world better just because it is performed directly compared to when it is performed after one made a promise to Classics. Per ENTAILMENT A, this means that there should not be more reason to allocate the funds to History directly compared to that of doing so after Baker promised it to Classics. This result conflicts with the Moral Cost View's assignment of deontic value (10 vs. 5).

Now, friends of the Moral Cost View may insist that the world in which Baker gives the funds to History directly is in fact a better world. This does not sound plausible to me. But in any event, my analysis at least highlights the inadequacy of relying on intuitions to evaluate the betterness of different possible worlds.

To remedy some of these issues I discussed, Earl Conee proposes the following:

- Conee's Motive-Centred View on Promising: when S promises to φ, there is zero deontic value in favour of keeping the promising, and there is zero deontic value against breaking the promising. However, there is positive deontic value in favour of S φ-ing for appropriate motives, and there is negative deontic value against S φ-ing for inappropriate motives.

Conee's contention is that keeping or breaking a promise per se has zero deontic value, although we should assign positive and negative deontic value to acts that are done for appropriate and inappropriate motives. By 'motives', Conee refers to the explanations for why the agent acted the way she did (see Guindon, 2016). The idea is rather straightforward: what matters is not just which acts are done, but also why the agent is performing them. For Conee, acting for appropriate motives is just acting in a way that exemplifies virtues and acting for inappropriate motives is just acting in a way that exemplifies vices (Conee, 2000: 413–15). So, it seems that Conee commits to

Relatedly,

With ENTAILMENT B and B`, Conee is drawing a connection between the deontic reason of an act (under the action-guiding conception) and the character assessment of the agent. This Motive-Centred View is able to deal with several problems identified above. In NEPOTISM, we should ascribe negative deontic value to Baker making the promise, because she made the promise out of nepotistic concern. Therefore, we have

This accords with our intuitive judgement, which is that Baker ought to allocate the funds to History directly.[4] Moreover, this also answers my objection comparing the act of {funds to History directly} with that of {funds to History (after one promised to allocate it to Classics)}. According to Conee, what carries negative deontic value is the act of making a promise, and hence the act of {funds to History} has the same deontic value either way (i.e., 10). By contrast, the sequence {funds to History without a promise} has a greater deontic value (i.e., 10) than {promise the funds to Classics and then give it to History} (i.e., 10-5=5).

Conee's Motive-Centred View can also make sense of DONATION. From the description of the case, we should assume that Pete is making a promise to do something he plans to do anyway. It then seems that what he did (making a promise) does not exemplify virtues and he did not make the promise for an appropriate motive. Therefore, per ENTAILMENT B`, he does not have more deontic reason to donate in virtue of having made a promise (note that, although Pete does not have more deontic reason to donate, he does have more aggregate reason to do so). Similarly, in GROCERY ROUTINE, we should not ascribe negative deontic value to Sandra breaking her promise because she did not act for an inappropriate motive.

So far, so plausible. However, here is a problem with the Motive-Centred View: There are cases where the agent promises to φ for an inappropriate reason, though she does not as a result have less deontic reason to {promise to φ andφ}. Likewise, there are cases where the agent promises to φ for an appropriate reason, though she does not therefore have more deontic reason to {promise to φ and φ}.[5] Consider:

COINCIDENCE: Dean Williams is expected to receive a fund which he can allocate to the Business or the Accounting department. Williams knows that Business needs the funds slightly more, and he also knows that if he promises the funds to Business, they will conduct a fair search and hire his niece. Not caring about the Business department and merely wanting his niece to get the job, Williams promises the funds to Business and later keeps his promise.

MISTAKE: Dean Lee, at another college, is expected to receive a fund which she can allocate to the Biology or the Geography department. She is under the impression that Biology needs the funds slightly more. Nevertheless, she errs on the side of caution and directs her assistant to conduct an audit. Soon after, Lee's assistant informs her that Biology does in fact have a greater need for the funds, and as a result, she promises the funds to Biology and later keeps the promise. As it turns out, however, her assistant made a mistake and it is the Geography department that actually had a greater need.

With COINCIDENCE and MISTAKE, another puzzle presents itself. In COINCIDENCE, the Motive-Centred View suggests that Williams has less deontic reason to {promise the funds to Business and follow through the promise} (compared to her not making the promise), as she made the promise for an inappropriate motive. As such, it becomes possible that {promise the funds to Business and follow through the promise} will have less deontic value than {promise the funds to Accounting}. This is counterintuitive, as Williams's reason for allocating the funds should not be susceptible to change in this way. When Williams made a promise for an inappropriate motive, this fact may impact on the moral worth of his action or the moral assessment of his character, but it should not change his deontic reason for action. Similarly, in MISTAKE, the Motive-Centred View suggests that Lee has more deontic reason to {promise the funds to Biology and follow through the promise}, as she made the promise for an appropriate motive. This also makes it possible that {promise the funds to Biology and follow through the promise} will have more deontic value than {promise the funds to Geography}. Again, it is very plausible that the deontic value for action should not be susceptible to change in this way.[6]

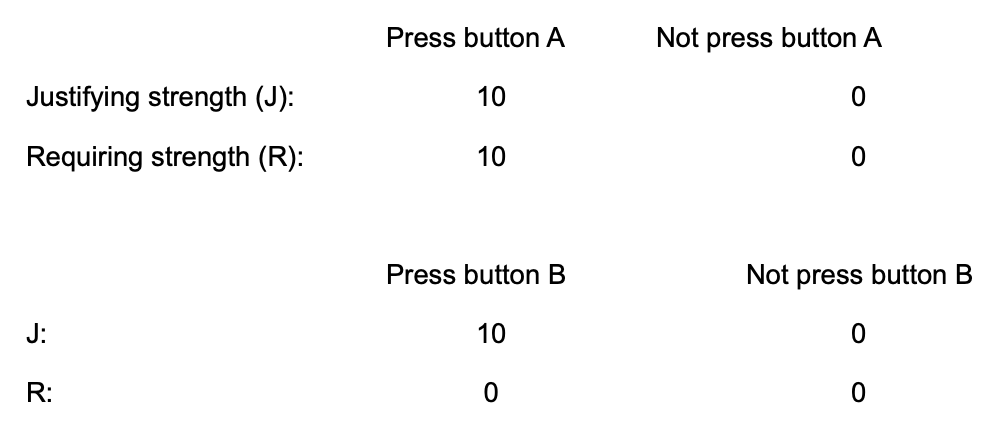

In this section, I will present my view, which I call promising as requiring. The view draws heavily on Joshua Gert's discussion on the two dimensions of reason. Gert (2007; 2012) notes that our ordinary talk about the reason for action is misleading. In effect, there are two distinct dimensions to reason, which Gert calls the justifying dimension and the requiring dimension. To illustrate, consider:

HEADACHE I: you are going to have a headache for a month. I can press a button – button A – which will cure you of the headache immediately.

HEADACHE II: you are going to have a headache for two months. I can press a button – button B – which will cure you of the headache immediately but will give me a headache for a month.

According to the standard view about 'the reason' for action, it seems that I have the same reason to press button A and B. This is because, from an impersonal perspective, the good produced by pressing either button is the same: suppose sparing someone a month of headache produces 10 units of good, then that will be the amount of good produced by pressing button A or pressing button B. But it seems quite plausible that I may be required to press A but not B – that is, pressing A is required whereas pressing B is merely permissible (i.e., supererogatory). Gert thinks that we can represent this difference between the two cases with the two dimensions of reason:

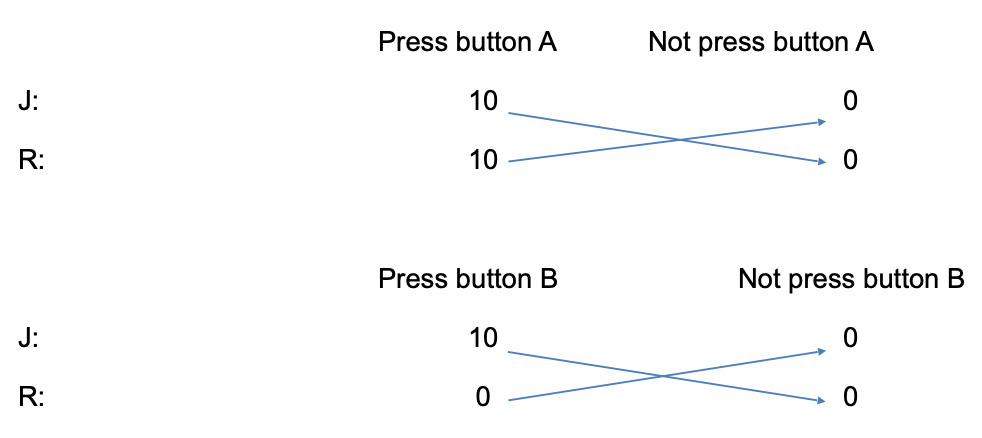

The justifying strength of φ-ing is the strength that will justify φ-ing whereas the requiring strength of φ-ing is the strength that will requireφ-ing. More precisely, the justifying strength of φ-ing is 'the reason' (as we conventionally conceive) in favour of φ-ing whereas the requiring strength ofφ-ing is 'the reason' against doing the alternatives of φ.[7] As such, Gert calls the justifying strength 'the permissible-making' strength and the requiring strength 'the impermissible-making' strength. To make sense of this, consider how φ-ing can be impermissible, permissible or required. To make φ-ing permissible rather than impermissible, we need reasons in favour of φ-ing; to make φ-ing required rather than merely permissible, we need reasons against doing the alternatives of φ. In other words, φ-ing is required just in case it is permissible and all of its alternatives are impermissible. As such, I think the justifying/requiring strength of φ-ing relates to the permissibility of φ-ing can be summarised as follows:

Recall the justifying/requiring strength of pressing A and B:

Pressing button A is required because its justifying strength is no less than the requiring strength of its (only) alternative (i.e., not pressing button A), and that its requiring strength is greater than the justifying strength of its alternative. By contrast, pressing button B is merely permissible because its justifying strength is no less than the requiring strength of its alternative, and its requiring strength is no greater than the justifying strength of its alternative. As such, the introduction of justifying/requiring strength accommodates our intuitions in both cases.[8]

We are, of course, still left with the question of what determines the justifying and the requiring strength of an act. Fully answering this question is beyond the scope of the paper. As such, I aim only to sketch a plausible view here. The justifying strength ofφ-ing is determined by the consequence of φ-ing. That is, for example, the justifying strength of pressing button A or B is determined by the amount of good it will produce. The requiring strength of φ-ing is often the same as its justifying strength, as the strength of the reason in favour of φ-ing is often that of the reason against doing φ's alternatives. However, the requiring strength ofφ-ing is also influenced by a range of other factors – among them is whatever justification that grounds supererogation. That is, whatever grounds the fact that pressing button B is supererogatory, it also figures into determining the requiring strength of pressing button B. For example, some (Kamm, 2006; Lazar, 2017; Lazar 2018b) ground supererogation in the cost to the agent – that is, roughly, the agent is not required to do the morally best act when it incurs an unreasonably large cost to her. So for them, what partly determines the requiring strength of φ-ing is the cost to the agent – when the cost is unreasonable, the requiring strength of φ-ing is zero. There are also those who argue that supererogation is grounded on considerations of autonomy, rational reasons, or 'person-protecting reasons' (e.g. Shiffrin, 1991; Bratman, 1994; Hurley, 1995). Whatever it is, these factors will influence the requiring strength ofφ-ing.

So much for the set-up. I am now in a position to present my own view of promising:

The view is straightforward: just as whatever grounds supererogation such as the cost to the agent will figure into determining the requiring strength of φ-ing, so will the fact about whether the agent promises to φ. And as whatever grounds supererogation will decrease the requiring strength, the fact that the agent promises toφ will increase it.

Consider how this view deals with various cases presented above. In NEPOTISM:

Without the promise, giving the funds to History is required, as its justifying strength is no less than the requiring strength of its alternative, and its requiring strength is greater than the justifying strength of its alternative (8).[9] With the promise, however, both giving the funds to Classics and giving the funds to History are impermissible, as the justifying strength of either option is less than the requiring strength of the other. That is, we have a case where the agent faces 'lesser-evil options' – a situation where none of the agent's options is permissible (see Kamm, 2006; Frowe, 2018).[10] This is plausible, as it reflects the fact that Baker should not have made the promise in the first place (i.e., by making the promise, she gets herself into a situation where all of her options are impermissible).

In DONATION, we will have

This gives us the intuitive result. Pete has not 'performed a morally better or preferable action in donating his $25' insofar as 'morally better' here is understood as an assessment of goodness. This is so because Pete's donation of $25 has the same justifying strength as Tom's $25. Nevertheless, Pete would have done something wrong had he not donated his $25, as donating is now required for him whereas it is merely permissible for Tom.

It may be argued that my view runs into trouble when it comes to GROCERY ROUTINE. For in that case Sandra not only has not done anything worse (which can be accommodated by the same justifying strength), she also has not done anything impermissible either (which may conflict with promising as requiring, as it would suggest an increase in the requiring strength). I believe that this fact can still be accommodated, as it seems plausible that the there is little requiring strength for Sandra to shop on either Saturday or Sunday to begin with. That is,

Now, even after making the promise, shopping on either day is permissible. The key here is that the requiring strength of shopping on either day is significantly lower than the justifying strength in the first place. This allows the fact that even after promising to shop on Saturday increases its requiring strength, shopping on Sunday is still permissible. I think this is the intuitive outcome, as presumably just because shopping on any day brings me some benefits (represented by its justifying strength), I am not required to do so even absent other alternatives. So, we should not expect the justifying and requiring strength to be identical for mundane actions like going to the grocery store.

Finally, promising as requiring can make sense of COINCIDENCE and MISTAKE too, as it does not make the deontic reason for action dependent on the agent's motives. Williams is required to allocate the funds to Business either way: its justifying strength is greater than the requiring strength of allocating the funds to Accounting and its requiring strength is greater than the justifying strength of allocating the funds to Accounting. These relations are not changed by him making a promise to Business. Similarly, promising as requiring gives us the result that Lee is required to give the funds to Geography either way.

In this paper, I have discussed what I call the puzzle of suboptimal promises: If making a promise gives us reason to do something, moral agents can sometimes promise to fulfil a less weighty obligation, and thereby ensure that they will do all they ought to do by fulfilling this obligation. I examined and rejected Smith's proposal for promising, which holds that keeping a promise has no positive deontic value, although breaking one has negative deontic value. The problem is that her analysis will also lead us to reject that breaking a promise has any negative deontic value. Conee, on the other hand, proposes that keeping or breaking a promise per se has zero deontic value, though we should ascribe positive or negative value depending on the motives. The problem is that this proposal still makes the deontic value for action susceptible to change in unacceptable manners.

To resolve these issues, I presented a view called promising as requiring, which holds that promising to φ increases the requiring strength of φ-ing. This view improves on Smith's account. To accommodate the intuitive fact that we ought to keep our promises (i.e., we have more aggregate reason to do what is promised), Smith proposes that instead of increasing the deontic reason for doing what is promised, we decrease the deontic reason for doing what is not promised. This helps her get around the puzzle of suboptimal promises. However, her proposal encounters its own problem as it is also not plausible that we should decrease the deontic reason for doing what is not promised. By contrast, my proposal suggests that we accommodate the thought that we ought to keep our promises by increasing the requiring strength of doing what is promised. This helps keep the justifying and requiring strength of doing what is not promised untouched, and therefore, it bypasses the problem facing Smith's account. In other words, what is changed by the agent making a promise to φ is only the properties of φ-ing, not those of its alternatives. My proposal also improves on Conee's account. For Conee, the key is to link the deontic reason for action to that of the assessment of the agent's character. This helps him deal with some problem cases, but it also makes the deontic value for action susceptible for change in other unacceptable ways. Promising as requiring, on the other hand, does not establish any such link and therefore does not introduce problematic susceptibility.

I've benefited greatly from the generous comments of three anonymous reviewers of this journal, to whom I offer my appreciation. I'd also like to thank my supervisor, Associate Professor Seth Lazar, for his comments on an early draft of this paper and his ongoing support. Finally, I thank the Assistant Editor of this journal, Sarsha Crawley, for her patience and support throughout the publication process.

[1] Kida Lin graduated from a Bachelor of Arts at the University of Sydney, and he is currently completing a Honours degree in philosophy at the Australian National University. His Honours thesis explores the morality of (in)effective altruism, and he is broadly interested in normative ethics and political philosophy. He hopes to begin a PhD in 2020.

[2] The question of wrongful promises is related to the debate between 'actualism' and 'possibilism'. See Goldman (1976, 1978). See also Jackson and Pargetter (1986), Feldman (1986), Zimmerman (2007) and Carlson (1999).

[3] This clarification is important because even the Conventional View can accommodate the fact that there are some cases where moral agents cannot manipulate their obligations. For example, if the deontic value of keeping and breaking a promise is +0.5 and -0.5 respectively, we will have:

If Baker does not promise Classics the funds:

Funds to Classics: 8

Funds to History: 10

If Baker does make the promise:

Funds to Classics: 8+0.5=8.5

Funds to History: 10-0.5=9.5

In this case, among {funds to Classics; funds to History; promise and funds to Classics; promise and funds to History}, Baker ought to give the funds to History directly.

[4] The deontic value of these four courses of action: 8 vs. 10 vs. 3 [8-5] vs. 5 [10-5].

[5] Note that here I focus on the sequence of 'making a promise to φ and then φ'.

[6] Note that for this to be a puzzle, it suffices if there are some cases where the deontic value for action is susceptible to change in this way. There are of course other cases where the 'gap' between two courses of action is so significant that it will not be changed by the value or disvalue of making a promise. Therefore, all I need here is that Conee's view makes it possible that the deontic value for action can be changed in this manner. Note also that this puzzle is slightly different from the original puzzle of suboptimal promises. The puzzle of suboptimal promises primarily concerns the manipulation of a moral agent's normative landscape while the puzzle here is not primarily about manipulation. In fact, Conee's view nicely rules out the possibility of manipulation by emphasising the motives for action. Nevertheless, both puzzles centre on the fact that certain views on promising makes a moral agent's normative landscape susceptible to change in unacceptable ways.

[7] The alternatives of φ can often just be not φ-ing (i.e., doing nothing), but they can include doing something else (i.e., ψ,-ing, ζ-ing, etc.).

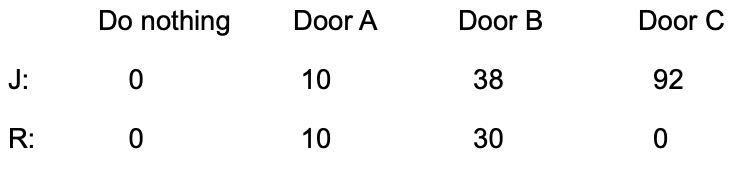

[8] We can consider a more complicated case (Lazar, 2018a: 15):

RESCUE: Suppose that you are outside a burning building. There are three entrances to the building. If you stay outside, and do nothing, then you will be fine, but ten strangers will die. If you enter door A, you will save one person's life, at no cost to yourself. If you enter door B, you will save that person and three others, at some non-trivial but not too serious personal cost – moderate bruising to your upper body, say. And if you enter door C, you will save all four of those, as well as six other people, at significant personal cost – full-body third-degree burns.

We can represent this case with a similar diagram.

In ascribing numerical value, I assume that: a) saving a person has +10 justifying strength; b) moderate bruising has -2 justifying strength; c) full-body third-degree burns has -8 justifying strength. This will give us the intuitive result: doing nothing or entering door A is impermissible whereas entering door B or door C is permissible. Entering door B is merely permissible as its justifying strength (38) is no less than the requiring strength of any of its alternatives but it is not the case that its requiring strength is greater than the justifying strength of all of its alternatives (i.e., the justifying strength of entering door C is 92). Similarly, we can get the result that entering door C is merely permissible.

[9] Notice that the comparison is 'localised' – that is, with regards to giving funds to Classics without the promise, only giving funds to History without the promise is considered its alternative. That is because if we consider all four courses of action alternatives to each other, we will have the implausible result that none of the actions is permissible.

[10] Note that there is a question as to how to determine which option to take in lesser-evil cases. Due to space constraint, I will not explore this question here – but I think a plausible answer is that which option to take depends on the gap between its justifying strength and the requiring strength of its alternative. In the diagram presented above, therefore, the agent should allocate funds to Classics (a gap of 2) instead of funds to History (a gap of 3). Of course, this depends on the numerical value we assign to the increase of requiring strength in virtue of the promise. If we assign an increase of +3 instead of +5, we will have the result that the agent should allocate funds to History. I think this is a plausible result because there are some instances where the agent ought to stick with a problematic promise and there are others where the agent ought not to. This feature can therefore be reflected in how to assign numerical value to the increase of requiring strength in virtue of the promise. Of course, the situation will be more complicated if there are multiple alternatives to φ-ing and all of which are impermissible.

Bratman, M. (1994), 'Kagan on “The Appeal to Cost”', Ethics, 104 (2), 325–32

Carlson, E. (1999). 'Consequentialism, alternatives, and acutalism', Philosophical Studies, 96 (3), 253–68

Conee, E. (2000), 'The moral value in promises', Philosophical Review, 109 (30), 411–22

Feldman, F. (1986), Doing the Best We Can: An Essay in Informal Deontic Logic, Dordrecht: Reidel Publishing

Foot, P. (2002), Moral Dilemmas: And Other Topics in Moral Philosophy, Oxford: University Press on Demand.

Frowe, H. (2018), 'Lesser-evil justifications for harming: Why we're required to turn the trolley', Philosophical Quarterly, 68 (272), 460–80

Gert, J. (2007), 'Normative strength and the balance of reasons', Philosophical Review, 116 (4), 533–62

Gert, J. (2012), 'Moral worth, supererogation, and the justifying/requiring distinction', Philosophical Review, 121 (4), 611–18

Goldman, H. S. (1976), 'Dated rightness and moral imperfecion', Philosophical Review, 85 (4), 449–87

Goldman, H. S. (1978), 'Doing the best one can', in Goldman, A. and J. Kim (eds) Values and Morals, Boston: Reidel, pp. 185–214

Guindon, B. (2016), 'Sources, reasons, and requirements', Philosophical Studies, 173 (5), 1253–68

Hurley, P. (1995), 'Getting our options clear: A closer look at agent-centered options', Philosophical Studies, 78 (2), 163–88

Jackson, F. and R. Pargetter (1986), 'Oughts, options, and actualism', Philosophical Review, 95 (2), 233–55

Kamm, F. M. (2006), Intricate Ethics: Rights, Responsibilities and Permissable Harm, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Lazar, S. (2017), 'Deontological Decision Theory and Agent-Centered Options', Ethics, 127 (3), 579–609

Lazar, S. (2018a), 'Accommodating Options', Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 100 (1), 233–55

Lazar, S. (2018b), 'Moral Status and Agent-Centred Options', Utilitas, 31 (1), 1–23

Owens, D. (2016), 'Promises and conflicting obligations', Journal of Ethics & Social Philosophy, 11 (1), 1–19

Reisner, A. (2013), 'Prima Facie and Pro Tanto Oughts', International Encyclopedia of Ethics, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781444367072.wbiee406, accessed 1 January 2019

Shiffrin, S. (1991), 'Moral autonomy and agent-centred options', Analysis, 51 (4), 244–54

Shiffrin, S. (2011). 'Immoral, Conflicting and Redundant Promises', in Wallace, R. J., R. Kumar and S. Freeman (eds), Reasons and Recognition: Essays on the Philosophy of T. M. Scanlon, available at http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199753673.001.0001/acprof-9780199753673-chapter-7, accessed 1 January 2019

Smith, H. M. (1997), 'A paradox of promising', Philosophical Review, 106 (2), 153–96

Smith, H. M. and D. E. Black (forthcoming), 'The morality of creating and eliminating duties', Philosophical Studies, 1–30

Thomson, J. J. (1990), The Realm of Rights. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Watson, G. (2009), 'Promises, reasons, and normative powers', in Sobel, D. and S. Wall (eds), Reasons for Action, Cambridge: Cambridge Universityof Press, pp. 155–78

Zimmerman, M. J. (2007), The Concept of Moral Obligation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

To cite this paper please use the following details: Lin, K. (2019), 'Promising to Do Wrong', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 12, Issue 1, https://reinventionjournal.org/article/view/442/400. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.