Bastian Hagmaier[1], Center for Global Sustainability and Cultural Transformation (CGSC), Leuphana University of Lüneburg

This article elaborates on sustainable entrepreneurs acting as change agents with a focus on their relevant key competencies for sustainability. For this purpose, the existing set of key competencies for sustainability by Wiek et al. (2011a) is combined with entrepreneurial competencies. The specific form of required competencies to act as change agents should inspire future design of curricula.

A literature review regarding key competencies, change agent concepts and sustainable entrepreneurs and their competencies forms the foundation. Ten semi-structured, qualitative expert interviews with entrepreneurs emphasise the relevance that the practitioners assign to each of the different competencies. Applying this framework of different competencies, the entrepreneurs' change agent behaviour identifies a specific competence profile of sustainable entrepreneurs of two axes: the importance of key competencies and the addition of specific entrepreneurial competencies. This is of high relevance to design specific programs to educate future change agents.

This research limits its findings to sustainable entrepreneurs. A larger number of interviews and an expansion to other expert groups, such as entrepreneurs without sustainable projects, could strengthen the results. With this article the author contributes to the debate key competencies and entrepreneurial competencies in higher education as well as their practical relevance.

Keywords: Key competencies for sustainability, entrepreneurship education, change agents, sustainable entrepreneur, entrepreneurial competencies, competence sets.

'Welcome to the Anthropocene!' (Nature Editorial, 2003: 709). What started as a catchphrase to raise awareness of global trends in an editorial in Nature in 2003 is now an officially recognised geological epoch in which human activities have grown to become significant geological forces (Steffen et al., 2015: 82). The Anthropocene is characterised by an unprecedented impact of humans on ecosystems, which ultimately poses a global threat to the long-term viability and integrity of social-ecological systems (Rockström et al., 2009). For the first time in history, human activities are the major driver contributing to global change, witnessed through accelerated climate change, loss of biodiversity and increasing social injustice (Leach et al., 2013: 85–86).

In response, the concept of sustainable development is interpreted as a pathway for a development within safe and just borders gained momentum (Raworth, 2012: 7). Today not only is sustainable development increasingly considered and discussed in the political sector, but also in economic research (Costanza, 1992). Recent changes led to an adjustment of the original Brundtland definition to include the security of people and the planet. The revised definition of sustainable development in the Anthropocene states: 'Development that meets the needs of the present while safeguarding Earth's life-support system, on which the welfare of current and future generations depends' (Griggs et al., 2013: 306). This definition is the guideline for this article.

Entrepreneurial activity can create this welfare for businesses and the ability to incorporate sustainability into their strategies is becoming increasingly more important (Figge et al., 2002: 269). In order to fully address the challenges that come with sustainability, more is needed than just a general commitment or greening of existing business models. Ultimately, it will depend on competent and committed multipliers, initiating sustainability-related projects, who act as change agents and not only want to, but are able to bring about change in economy and society as such (Caldwell, 2003; Hesselbarth and Schaltegger, 2014).

Entrepreneurs who are able to manage and participate in value-creating processes can play a pivotal role and act as these change agents. As sustainable entrepreneurs they innovate, take advantage of opportunities and create an additional value. Entrepreneurial activities can bring change by introducing new and more sustainable business models and ultimately allow for transformations towards the sustainability of markets and society (Schaltegger and Wagner, 2011). Sustainable entrepreneurs aim not just to reduce the negative environmental and social impacts of their organisations, but also to create positive contributions to sustainable development (Hockerts and Wüstenhagen, 2010).

To do so, entrepreneurs will need a set of specific abilities that encompass motivation, skill and experience, which make it possible to be entrepreneurial (Moberg et al., 2014: 14–20). While there is a general agreement on the need for such competencies, little is known about what these specific competencies are and how they can be developed (Frese and Gielnik, 2014). With this article we address that gap and investigate the specifics of competencies for sustainable entrepreneurs. Sustainable entrepreneurs act as sustainability experts and entrepreneurs, so the competence framework for sustainability experts developed by Wiek et al. is used and analysed. On the one hand, the concept of key competencies for sustainability (Wiek et al., 2011b: 6–8) is joined with insights into general entrepreneurial competencies. On the other hand, we draw on feedback from entrepreneurial practitioners to capture their insights as experts of sustainable entrepreneurship.

Specific change agent skills might be acquired via specific teaching formats (Svanström et al., 2008: 346). Such skills related to sustainability can be defined as the power to collectively analyse complex systems within different spheres (i.e. society, environment or economy). These can be analysed from a local to global scale and taking cascading effects, passivity, feedback loops and other systemic features into account (Wiek et al., 2011a: 207). Teaching formats have successfully educated students in those competencies including their real-world application, but their use and relevance in professional careers has not been analysed yet. This causes the need for deeper and more specific analysis of key competencies for sustainability depending on specific professional roles to prove their effectiveness (Wiek et al., 2011a: 204).

This work aims to examine which key competencies sustainable entrepreneurs need to find long-term solutions as change agents for sustainability. This research will be conducted in two main steps. First, a literature review regarding the overall concept of key competencies for sustainability, including their development and specific definitions for all six key competencies, will be conducted. This classification will be used in the second step by an analysis of the specific target group of sustainable entrepreneurs based on qualitative interviews.

The model of entrepreneurship as 'the process of doing something new and something different for the purpose of creating wealth for the individual and adding value to society' (Kao, 1993: 69) can be defined in three parts. Entrepreneurship is the process of making changes, doing something more effectively than others, and identifying opportunities beyond the resources that are currently under control (Kao, 1993: 69). Sustainable entrepreneurship can be described as a form of creating economic and societal value by using innovative, market-oriented and personality driven approaches to achieve a 'break-through [for] environmentally or socially beneficial market[s]' (Schaltegger and Wagner, 2011: 226). In addition to these positive benefits, discovering and developing economic opportunities might also initiate and support the 'transformation of a sector towards an environmentally and socially more sustainable state' (Hockerts and Wüstenhagen, 2010: 482). Within the scope of this article, sustainable entrepreneurs are defined as individuals who act as chief executive officers and/or founders of their own sustainability-oriented organisation and foster the process of sustainable entrepreneurship. It is important to acknowledge the role of being an entrepreneur within the hierarchy of a larger organisation which may require an adjustment to the competencies for that setting. More insights on the required competencies are necessary as '(start-up) businesses are in need […] to address sustainability challenges' (Ploum et al., 2017: 2).

The role of change agents in organisations has raised enormous interest over the last two decades (Caldwell, 2003: 131). Established out of the economic discipline of management, a change agent can be considered as an 'internal and external individual […] responsible for initiating, sponsoring, directing, managing or implementing a specific change initiative, project or complete change programme' (Caldwell, 2003: 139–40). Individuals who act as change agents can be characterised as driving forces in an organisation's change process and have the leadership to convince and motivate others to leave established pathways and inspire their employees (Hesselbarth and Schaltegger, 2014: 26).

One specific form of change agents is 'change agents for sustainability' (Hesselbarth and Schaltegger, 2014: 24). It describes people who work on social and ecological problems with entrepreneurial tools. The goal is to contribute towards a sustainable transformation of the whole of society through implementing sustainability management as common practice in organisations. These individuals can either be decision makers in a company or people who promote changes out of their position in a lower hierarchy level. They might also have no specific role related to sustainable development (Hesselbarth and Schaltegger, 2014: 26).

The concept of key competencies is increasingly popular and witnesses a general turn from an input to an output orientation in teaching and learning (Hartig et al., 2007: 3–4). Gnahs describes competence as, 'a potential of knowledge and skills that enables to act appropriately' (Gnahs, 2011:18–19). What makes this competency approach so special is that it does not focus on a specific situation or task, but presumes that it consists of a set of abilities to deal with various complex demands. For this, the interplay of internal structures such as cognitive, emotional and motivational dispositions is necessary. Weinert (2001) explains skills in more detail, based on the original competence definition of Gnahs. He refers in particular to 'intellectual abilities, content-specific knowledge, cognitive skills, domain-specific strategies, routines and subroutines, motivational tendencies, volitional control systems, personal value orientations, and social behaviours'.

The focus on competencies to successfully master the many challenges of an increasingly complex world acknowledges the mediating role of attitudes and motivational aspects in addition to knowledge, and emphasises the autonomous learner's abilities rather than a specific behaviour as a learning outcome. The term key competencies represents a qualitative extension that highlights the significance of certain competencies. Key competencies are relevant across different spheres of life and for all individuals (Rychen and Salganik, 2003: 54). They do not replace, but rather comprise domain-specific competencies, which are necessary for successful action in certain situations and contexts.

In the literature on sustainability-related competencies, a number of approaches offer frameworks that define such learning objectives. They share the goal of enabling people not just to acquire and generate knowledge, but also to reflect on further effects and the complexity of behaviour and decisions in a future-oriented, global perspective of responsibility (Barth, 2015).

In a systematic review, Wiek et al. (2011b) identify five competencies for sustainability based on a broad literature review: systems-thinking competence; anticipatory competence or future thinking; normative competence or value thinking; strategic competence; and interpersonal competence. Together they form a sixth, integrative, competence, the problem-solving competence. The systems-thinking competence supports the understanding of a complex problem constellation. The central ability is 'to collectively analyze complex systems across different domains (society, environment, economy, etc.) and across different scales (local to global)' (Wiek et al., 2011a: 207). This competence is a central competence for future sustainable entrepreneurs. The systematic understanding of change processes is continuously ongoing. Furthermore, it also has a high relevance to some sustainable entrepreneurs, leading and establishing their company in its complex structure. The anticipatory competence reinforces the anticipation of the effects of sustainability problems and consideration of alternative future scenarios with or without intervention. It is the capability to 'analyze, evaluate, and craft rich “pictures” of the future' (Wiek et al., 2011a: 207–09). The normative competence guides the selection of a more desirable sustainable future (Wiek et al., 2011a: 209). Necessary skills are to specify, compare, apply, reconcile and negotiate sustainability values, principles, goals and targets.

The strategic competence is used to develop a strategy working towards the chosen future. Hence, 'the ability to collectively design and implement interventions, transitions, and transformative governance strategies' (Wiek et al., 2011a: 210) is crucial to develop such strategic thinking. These new future strategies require a change of perspectives to transfer the new visions into action (Hesselbarth and Schaltegger, 2014: 26). This is important as understanding 'what must be done, why, when, how, and by whom' (Ford and Ford, 1995: 557) is crucial to the success of a change process. Entrepreneurs, as the most influential individuals in a business, act largely as decision makers (Westhead et al., 2005: 395). Interactions with various stakeholders require an interpersonal competence to handle relations between people (Wiek et al., 2011a: 206). Required abilities are expertise in project management, communication skills, collaboration, leadership, cultural understanding and empathy (Wiek et al., 2011a: 211). Going beyond that, the potential of using human capital from the entrepreneur as well as initiating this potential in others is one precondition for successful entrepreneurship (Westhead et al., 2005: 397). Along these lines, Ford and Ford consider 'change as a communication-based and communication-driven phenomenon' (Ford and Ford, 1995: 541) where motivation is a crucial factor of success (McMullen and Shepherd, 2006: 138). Furthermore the ability to create and maintain network figures prominently, as social networks may lead to a higher business success (Frese and Gielnik, 2014: 426; Svanström et al., 2008: 348). A potential that entrepreneurship has is the huge market impact by the formation of new companies which is an already widespread concept (McMullen and Shepherd, 2006: 132; Shane and Venkataraman, 2000: 223).

The integrated problem-solving competence enables individuals to apply different frameworks to complex sustainability problems and developing practical solution options. Thus, it includes conducting integrated problem analysis, sustainability assessments and visioning as well as strategy building (Wiek et al., 2011a: 205). Key competencies for sustainability build upon general skills and knowledge (Wiek et al., 2011a: 214). Entrepreneurial competencies for the entrepreneurship process mentioned above are related to the role of being an entrepreneur and can cover divergent thinking, active information search, business opportunity identification and innovativeness of product/service innovations (Frese and Gielnik, 2014: 417–18).

The question of which competencies are relevant for the professional role of sustainable entrepreneurs acting as change agents guides this research. To identify these competencies and their perceived importance and practical relevance, semi-structured qualitative expert interviews were carried out. As the research field is partially unknown, existing sources are used to structure the field, concretise the research questions and identify the first experts (Wassermann, 2015: 55).The interviews were analysed in a procedural model by using qualitative content analysis based on Mayring (2014: 39).

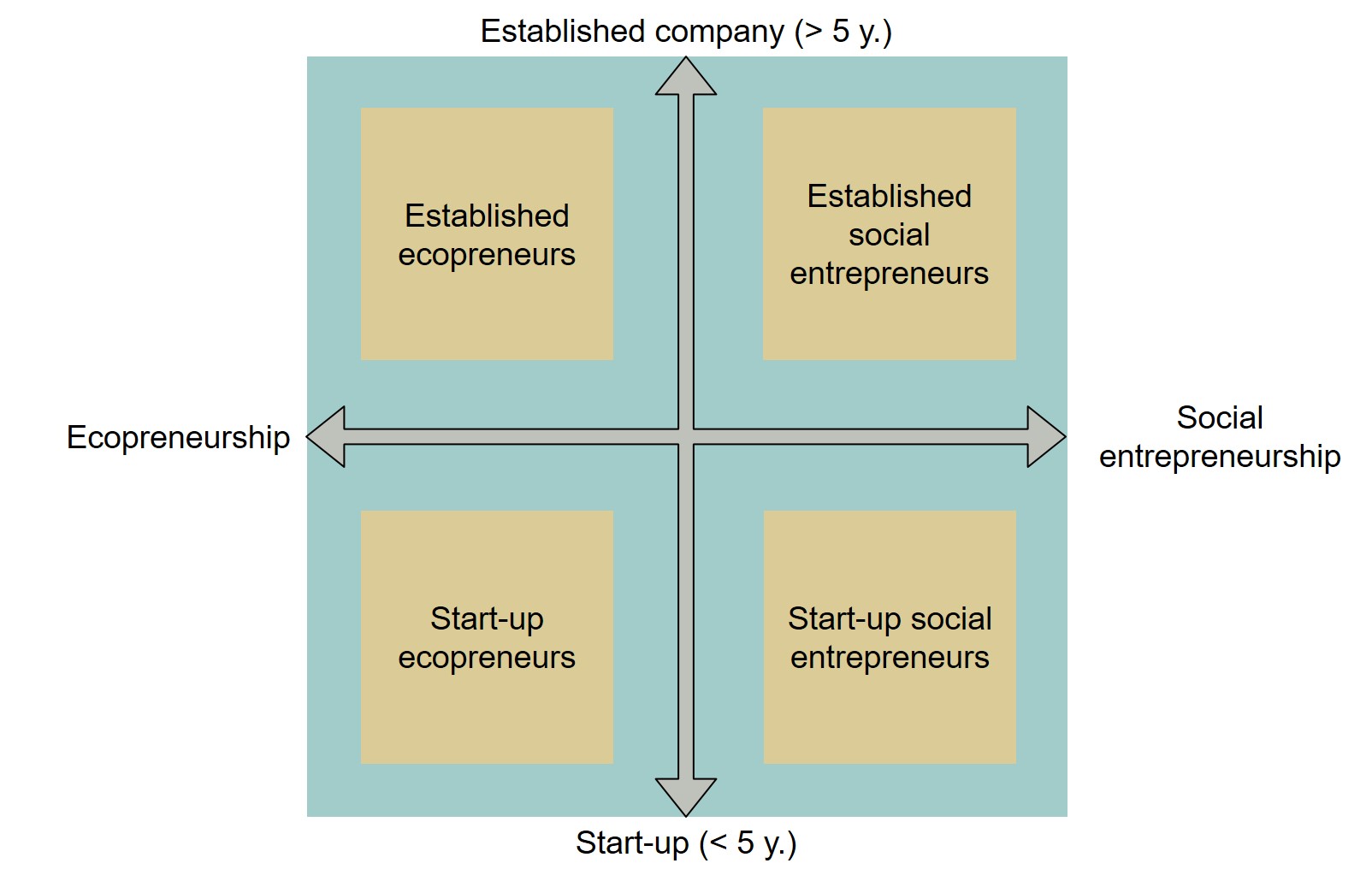

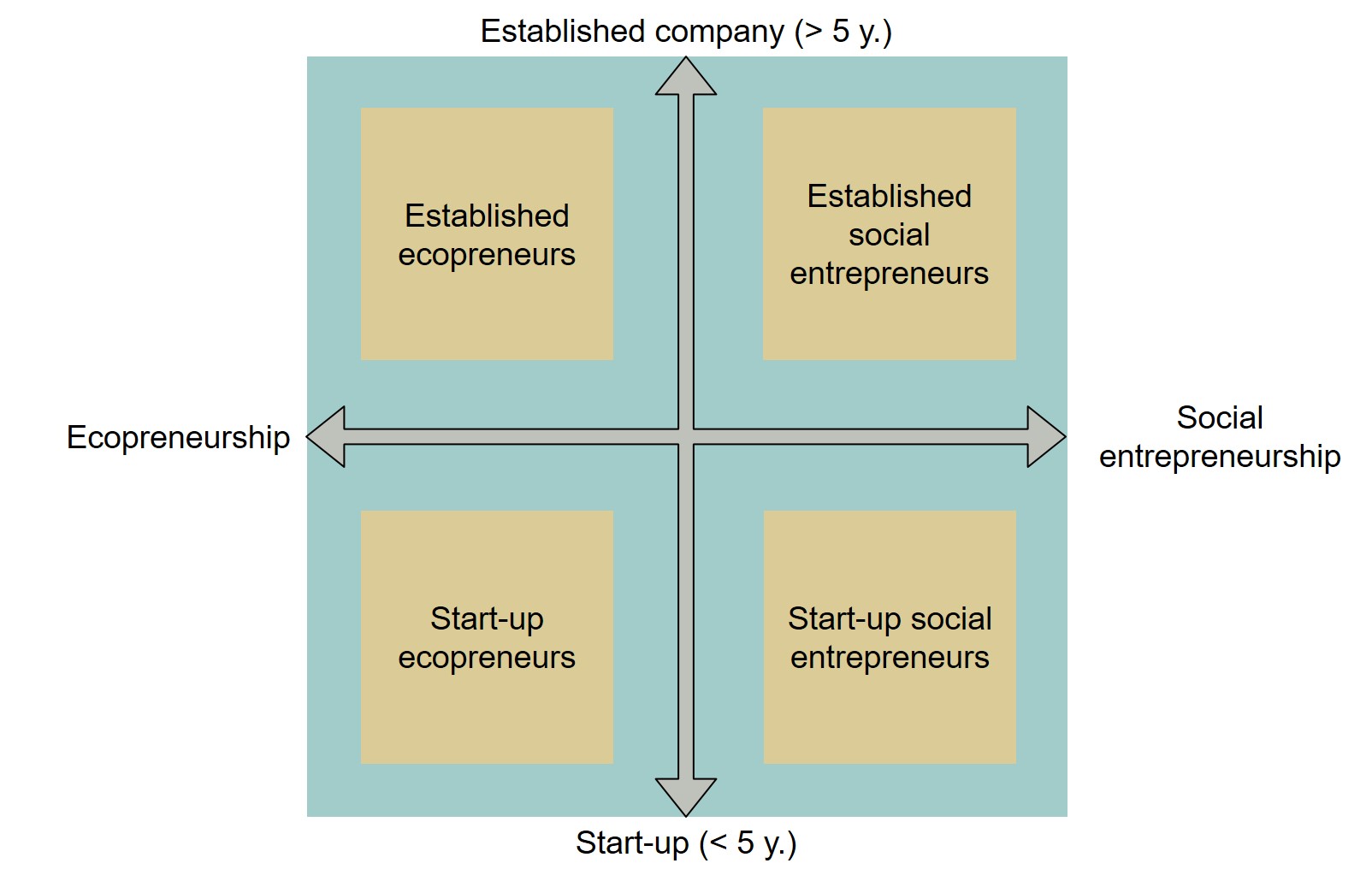

Interviewees were selected with a maximum of variation in potential perceptions and answers. The theoretical sampling was used to select ten appropriate interviewees, explained in detail by our colleagues Hesselbarth and Schaltegger, to identify different interview partners (Glaser and Strauss, 2010: 61–91; Hesselbarth and Schaltegger, 2014). The two criteria for selection were the field of companies' business activities and the interviewees' experience in the business sector (see Figure 1).

Business experience is a relevant criterion to differentiate entrepreneurs whereas the industrial sector in which they operate might influence the activities of the entrepreneurs and thereby the required competencies (Westhead et al., 2005: 396). The measurement is the experience in entrepreneurial activities in years, where up to five years' experience is considered a start-up and experience of more than five years is considered an established company (Ucbasaran et al., 2008: 164; Westhead et al., 2005: 412). The focus of this work is on the individual as an entrepreneur and their individual experience, therefore a distinction by years of experience is appropriate as it considers different types of entrepreneurs in the same manner. The age of a venture in years is not applicable for competency evaluation, as their development does not relate directly to entrepreneur's development (Westhead et al., 2005: 394).

Sustainable entrepreneurs can address both environmental and social advantages. Sub-types of sustainable entrepreneurs acting with a specific focus are ecopreneurs and social entrepreneurs. While ecopreneurs aim to solve environmental problems and create economic value, social entrepreneurs intend to solve societal problems and create value for the society (Schaltegger and Wagner, 2011: 224).

The final sampling includes ten experts from various backgrounds, including seven established entrepreneurs (three social entrepreneurs and four ecopreneurs) and three start-up entrepreneurs (one social entrepreneur and two ecopreneurs). The age distribution covers one expert between 21 to 30 years, three interviewees between 31 to 40 years and six experts between 51 and 60 years old. The gender distribution is 30% female and 70% male participants.

The interview focuses on the specific role of sustainable entrepreneurs. A pilot of the interview questions was carried out to verify their functionality and that it would gain results in the appropriate manner (Bogner et al., 2014: 34). Interviews were conducted in January 2017 with an average duration of 30 minutes. Experts were not given the descriptions for the competencies provided.

The questionnaire is structured in four thematic blocks with main questions where each block deals with a central question and leads over to the following one (Bogner et al., 2014: 28). The guideline starts with an introduction block consisting out of two questions regarding the current business and the primary responsibilities. The next section addresses activities and own contributions of each entrepreneur. The main questions here are 'Currently, how do you see your business contributing to sustainability? What are the primary goals of your business activities?'. Accompanied by four sub-questions such as 'What activities did (or do) implement in order to achieve the outcomes?' the aim is to receive an overview of different contexts and roles the interviewee acts in. The third block addresses skills and knowledge and thereby the awareness of competencies and has three main questions. The last section addresses future projections regarding entrepreneurship and its potential in contributing towards transformational sustainability. The enquiry includes questioning skills and knowledge that a successful entrepreneur needs today as well as in future.

To code the data, a prior defined code book was used to guide the interpretation of the interviews (Mayring, 2014: 97). Its creation followed a three-step process of first defining nominal categories, then anchoring examples, and finally formulating coding rules (see Table 1 for an example). Categories were based on key competencies for sustainability (Wiek et al., 2011b: 6–8), entrepreneurial competencies and other competencies of relevance such as critical thinking and basic communication skills. Newly emerging concepts were integrated as In-Vivo Codes.

|

Category |

Coding rules |

Example of results |

|

Anticipatory competence or future thinking |

Exploring different future pathways and solution visions Applying scenario methodology and forecasting from statistical and simulation models Back casting and envisioning methods Anticipatory multi-methodologies as well as participatory anticipatory approaches |

'Adaptability' 'You also need flexibility' |

|

Entrepreneurial competencies/business competencies |

Divergent thinking, active information search, business opportunity identification and innovativeness of product/service innovations Other business and entrepreneurship related competencies |

'Observation of the market' 'Creativity, tenacity and resilience' 'Recognising opportunities' |

A deductive code system was derived during the analysis of the interview transcript. The generated results were then compared with regard to the frequency of occurrence and the specific descriptions related to the key competencies for sustainability.

Data from the interviews confirms and expands the relevance of the three competence areas: (1) key competencies for sustainability, (2) entrepreneurial competencies, and (3) general competencies. It also shows a twofold role of entrepreneurial activities: on the one hand there is a specific context in which key competencies for sustainability are perceived and utilised, and on the other hand they form a distinct area of competencies that are specifically addressed through sustainable entrepreneurs.

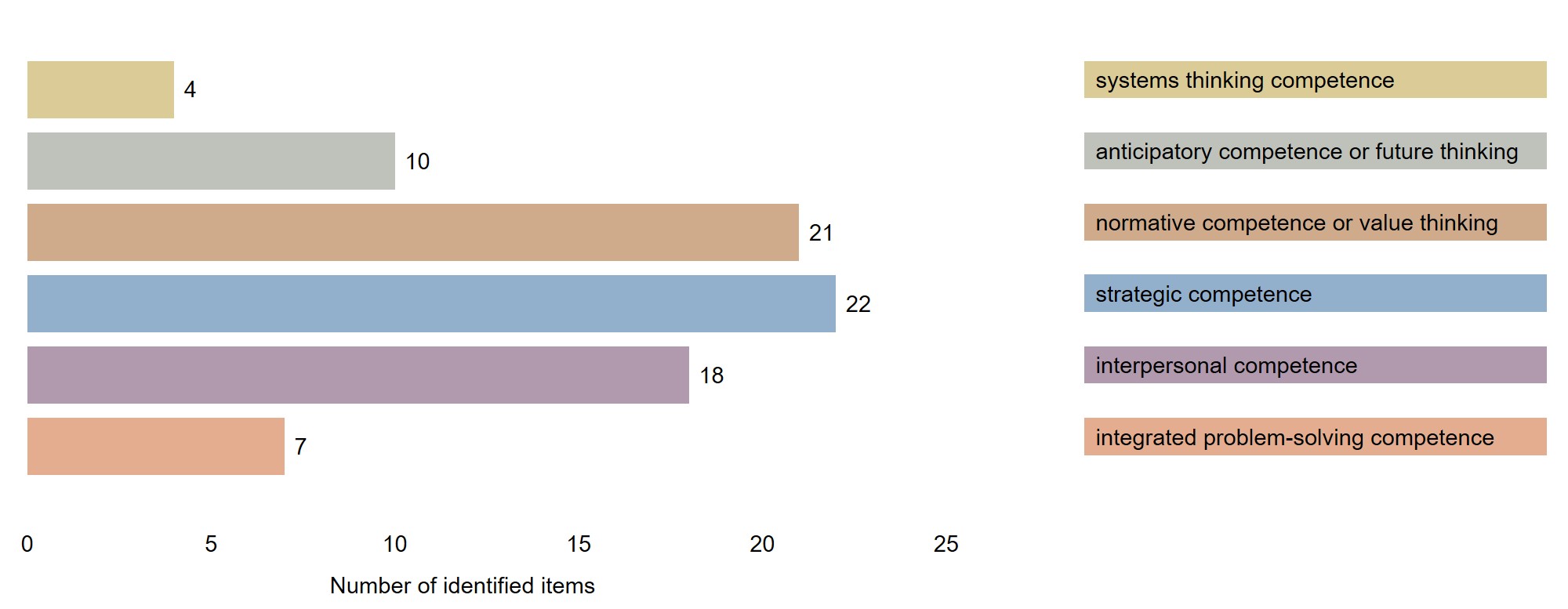

Across all ten interviews key competencies for sustainability are addressed 82 times, entrepreneurial competencies have 49 related items, and the regular competencies are characterised by 31 items. Thereby the identified key competencies are not just mentioned for themselves, but in connection with complementing entrepreneurial and regular competencies. This leads to an area of conflict between key competencies as broad and transferable skills and very specific application of these competencies. The following paragraphs provide a short description of the specific application and context in which each key competence for sustainability is described. Figure 2 shows the number of identified items for each competence. Results fit the selected categories as all competencies have several items. These numbers provide some information, but the focus is on the content and relation to entrepreneurial competencies. The most prominent are normative and strategic competence, followed by the interpersonal competence.

There is a high awareness of anticipatory competence which was directly referred to by the interviewees as 'adaptability' (ID#01, par. 44) or 'you also need flexibility' (ID#04, par. 30). One ecopreneur explains that he has already taken existing companies into account to develop his own sustainable business (ID#02, par. 28). Anticipatory competence is not only relevant to identify the companies' values in the beginning, it becomes more important in the 'conception of projects to construct them in a way that they meet the requirements' (ID#03, par. 10).

Items for value thinking are related to the values, beliefs, goals and criteria for activities of the organisations. One entrepreneur stated, 'I think it's simply about other values' (ID#09, par. 38) when addressing important factors of successful sustainable entrepreneurship. Addressing the system level via a normative approach, another expert explained that 'we need to rethink completely. Today, companies are no longer capital-oriented, but socially or publicly oriented' (ID#02, par. 40). It is essential to 'keep both feet firmly on the ground' (ID#03, par. 20) when acting in the field of sustainability. Normative competence and its relevance were expressed as 'the overall goal to make the world a little better place in every little detail' (ID#07, par. 10).

Regarding the strategic competence, one expert described that he 'developed future strategies' (ID#10, par. 6) as part of his function as leader in the company. Another entrepreneur described her duties as being responsible 'for the development of the programs in the organisation; so how and where to is it going' (ID#04, par. 6) as she builds up new opportunities to introduce her customers to a more sustainable lifestyle. When it comes to implementing such change, decision making has a high relevance for entrepreneurial actions. The main step is to 'put projects into practice' (ID#09, par.16). Crucial actions within strategic competence are to perform well in decision making (including ongoing evaluation of actions) (ID#03, par. 8), a precise deliberation on your own perception (ID#06, par. 28) and moving from a niche to trendsetter and increase the overall societal impact (ID#04, par. 14).

Related to human resources, interpersonal competence was mentioned as 'enthusiasm among employees' (ID#02, par. 10). It was described as 'the empathy in another person or partners and willingness/motivation to discover their interests' (ID#03, par. 14), which is an important personal skill to develop a competence regarding interactions with others. The relevance of successful exchange in networks and alliances was explained by the 'exchange with different stakeholders' (ID#03, par. 20) has a high impact on goal setting. To be successful in these relationships with other people, being authentic was mentioned as key issue. Overall it was described that acting 'as a motivator' (ID#10, par. 27) and to actively 'build-up networks' (ID#07, par. 28) can lead people to 'emerge from society and act as a stimulus' (ID#10, par. 27) to facilitate sustainability problem solving.

An interviewee addressed the integrated problem-solving competence as 'self-evident initiatives, recognising problems, seeing solutions and applying and adapting them' (ID#01, par. 42). The integrative competence could also be identified in mentioned activities. For example, the founder of a consulting agency figured out 'when we often come and bring the issue of sustainability, everyone else thinks think we just cost money. This is true, but we are also showing how money can be saved through many measures' (ID#09, par. 8). He presented how it is possible to develop practical solution options for acting against prejudices of his customers to implement sustainability in their business activities.

Overall, entrepreneurial competencies are described as being equally as relevant as key competencies for sustainability. There are 49 items describing the different entrepreneurial competencies.

In employee interaction, 'human resources management' (ID#06, par. 6 and ID#08, par. 18) was described by several interviewees as crucial task for sustainable entrepreneurs. This role was also addressed by the required 'leadership competence' (ID#03, par. 22) which was supported by several statements in the interviews.

The opportunity identification was described quite often as 'recognising opportunities' (ID#06, par. 28) or to 'risk starting something new' (ID#04, par. 23). An entrepreneur saw the core of being successful in the differentiation in opportunity identification, 'if one wants to be entrepreneurially successful, then one shall behave different than the majority of the population' (ID#06, par. 28). Another expert supported this approach with the goal to 'develop creative solutions' (ID#09, par. 16).

The 'analysis of the market and the link to the company goal' (ID#02, par. 16) was mentioned as a fundamental success factor by the interviewed expert. The role of taking entrepreneurial action includes giving 'impulses and ideas on how we present ourselves on the market' (ID#06, par. 8).

Marketing and sales was described as having 'a bit of marketing expertise' (ID#07, par. 28). In addition another entrepreneur saw drawing 'process visualisation and user stories' (ID#10, par. 16) as an important part in creating the image of his firm.

Activities in finance were mentioned as important in some of the interviews as the goal of these is to make 'financial profit' (ID#04, par. 6) a reality. This is interpreted in various ways of execution, for example as 'potential financing, foundation, fundraising' (ID#01, par. 12).

There are 31 items identified in the code of regular competencies. The most prominent content in all items is communication related competencies. Such a 'communication competence' (ID#03, par. 22) was directly mentioned and addressed by more than half of the entrepreneurs. On behalf of this interaction with other people it is important to have a 'flair for people, situations, and for needs' (ID#07, par. 28). Experts also addressed rhetorical expertise as important to their success. These are key skills when it comes 'to hold their own workshops or lectures as an expert also to be perceived professionally' (ID#01, par. 32). 'Willingness to learn' (ID#06, par. 28) adapting from experiences and the development of tacit knowledge were also described in the regular competency items. This is expressed as 'the principle of trial and error, learning from the results, reflecting if this is tested quasi-playfully' (ID#10, par. 30). Often, the regular competencies were mentioned in relation to key competencies supporting the application. Overall, including the regular competencies was useful to complement the description of the required competencies to act as change agents.

It is the competence profile of successful sustainable entrepreneurs that brings together the two axes of key competencies for sustainability and entrepreneurial-specific competencies that are of importance for sustainable entrepreneurs as well. The two axes complement each other and form a specific competence profile, supported by regular competencies that describe sustainable entrepreneurs as highly relevant agents of change in the sustainability transformation.

The results clearly indicate that sustainable entrepreneurs represent a specific competence profile, going beyond key competencies for sustainability. This is characterised by the clearly identified competencies of relevance for sustainable entrepreneurs acting as change agents. A specific contextualisation elaborates this specific profile even more, e.g. in future thinking developing a transition strategy is supported by the principle of trial and error to create multiple scenarios, combining sustainability competencies with entrepreneurial tools. This competence profile can be described along these two axes.

First, sustainable entrepreneurs reconfirm the importance of key competencies for sustainability as they are specified by Wiek et al. (2011b). Data indicates not only the existence and importance of these competencies but also that entrepreneurial activities form a specific context in which these competencies come into play and need to be applied. For example, the need for flexibility and adaptability, essential for entrepreneurs, which can be connected to the anticipatory competence.

While the need for future thinking is confirmed for entrepreneurial activities in general as well, it is also contextualised in companies as adaptation based on other competitors and with regards to changing conditions in the environment of a company. Furthermore, dealing with future scenarios is a way to identify entrepreneurial opportunities beforehand as central part of action enabling change affecting the world (Frese and Gielnik, 2014: 417–18).

Strategic competence, which can be seen as a third example of how these sustainability key competencies are contextualised in entrepreneurial activities, plays an important role for sustainable entrepreneurs. This is also mentioned in the interviews as power to implement strategies and the duty to decide on essential issues. More detailed descriptions of the strategic changes to be achieved refer to the potential as the huge market impact of entrepreneurship by the formation of new companies.

The second axis that forms the specific competence profile of sustainable entrepreneurs is the addition of entrepreneurial-specific competencies that complement the sustainability-specific key competencies. Here six different areas are addressed: use of human capital; opportunity identification; market analysis; marketing and sales; finance; and networking and relationships. While there are several overlaps and strong links to key competencies for sustainability, we argue that these areas represent distinct competencies for entrepreneurial and business competencies that complement sustainability-related competencies. While it is part of the interpersonal competence to be able to interact with other and to convince other stakeholders both inside and outside of the area of entrepreneurial activities, there are specific competencies for entrepreneurs that go beyond that. Motivation as a crucial factor of success, as described by McMullen and Shepherd (2006), is also confirmed in this study as entrepreneurs describe the enthusiasm and motivation as key factors of their actions.

It must be kept in mind that the small sample size and the methodology used make this a qualitative, exploratory study. Therefore, additional research is required to confirm the findings and extend to a statistical significance.

In this study we investigated the perceived relevance of competencies to be a successful sustainable entrepreneur. Although the study is of explorative nature and the relatively small sample size by no means is exhaustive, it offers relevant insights in what competence profile enables the sustainable entrepreneur best to act as a change agent. Results can be linked to both the discourse about key competencies for sustainability and about entrepreneurial competencies. Furthermore, these sustainability competencies are complemented by general competencies of successful entrepreneurs. Thus, it is only if we understand the competencies of sustainable entrepreneurs as a combination of both key competencies for sustainability and entrepreneurial competencies that we fully capture their potential to become a change agent. This calls for an increasing relevance to include both competence sets as interrelated in future curricula design, not only in specific programs but also on a general level.

Following the development of these specific competencies needs a meaningful learning setting. This may be best characterised by insights of both sustainability education and entrepreneurial education. To fully support the specific competence profile of a sustainable entrepreneur we will also need tailored teaching and learning environments where the specific links between key competencies for sustainability and entrepreneurial competencies can be made and experienced. Thus, this will need contextualised learning to happen in which students can learn how to act as a sustainable entrepreneur and to contribute to change through entrepreneurial activities.

Our findings have a high importance for specific programs, such as the Global Sustainability Science program, a double degree master's program of Arizona State University and Leuphana University Lüneburg. Here we have created a new curriculum addressing the urgent need for highly qualified graduates being able to act as change agents for sustainability in different fields, including entrepreneurship. This work shows that an integrated interdisciplinary teaching approach addressing both entrepreneurial and sustainability-related competencies is the right way to go. How this can be best supported and rolled out to all kinds of programs and beyond higher education must be the focus of future studies.

[1] Bastian has a keen interest in global sustainability and entrepreneurship and innovation, achieving a BSc in International Business Administration & Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Sciences from Leuphana University of Lüneburg, as well as achieving his MSc in Global Sustainability Science from Leuphana University and Arizona State University. His expertise ranges from international business development via entrepreneurship & innovation to implementing sustainable solutions complemented by in-depth experience in project management, research and training as well as consultancy for early-stage businesses.

Being globally minded and dedicated to strategic thinking Bastian aims to utilize proven research, management and teamwork skills to advocate for and implement sustainability within organizations and beyond. Bastian looks forward to being challenged by new projects and aims to have a positive impact for business, stakeholders, our society and environment. Bastian’s profile can be found at www.linkedin.com/in/bastianhagmaier

I would like to acknowledge that this work would not have been possible without the support of others. First of all, I would like to thank my supervisors Daniel Lang and Matthias Barth for their continuing support and time spent to support me in this project and enabling this opportunity.

The advice regarding my initial research approach and further details of Maike Buhr, Michael Gielnik, Jantje Halberstadt and Adalbert Pakura was a great experience for me and I highly appreciate all support you gave me.

Without the ten great sustainable entrepreneurs who supported this work with their knowledge and time for interviews, these results would be there. Thanks to each of you as it was not only gathering data but also a great pleasure to meet you all.

Figure 1: Matrix for theoretical sampling of sustainable entrepreneurs.

Figure 2: Number of identified items within key competencies for sustainability.

Table 1: Examples for coding.

Abson, D. J., J. Fischer, J. Leventon, J. Newig, T. Schomerus, U. Vilsmaier, H. von Wehrden, P. Abernethy, C. D. Ives, N. W. Jager and D. J. Lang (2017), 'Leverage points for sustainability transformation', Ambio, 46 (1), 30–39

Barth, M. (2015), Implementing sustainability in higher education: Learning in an age of transformation, London: Routledge

Barth, M., G. Michelsen, M. Rieckmann and I. Thomas (eds) (2016), Routledge handbook of higher education for sustainable development, Abdingdon: Routlege

Bogner, A., B. Littig and W. Menz (2014), Interviews mit Experten: Eine praxisorientierte Einführung, Qualitative Sozialforschung, Wiesbaden: Springer VS

Caldwell, R. (2003), 'Models of Change Agency. A Fourfold Classification', British Journal of Management, 14 (2), 131–42

Costanza, R. (1992), Ecological economics: The science and management of sustainability, New York: Columbia University Press

Figge, F., T. Hahn, S. Schaltegger and M. Wagner (2002), 'The sustainability balanced scorecard – linking sustainability management to business strategy', Business Strategy and the Environment, 11 (5), 269–84

Ford, J. D. and L. W. Ford (1995), 'The role of conversations in producing intentional change in organizations', Academy of Management Review, 20 (3), 541–70

Frese, M. and M. M. Gielnik (2014), 'The Psychology of Entrepreneurship', Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1 (1), 413–38

Glaser, B. G. and A. L. Strauss (2010), Grounded Theory: Strategien qualitativer Forschung, Göttingen: Huber & Co.

Gnahs, D. (2011), Competencies, Berlin: Verlag Barbara Budrich

Griggs, D., M. Stafford-Smith, O. Gaffney, J. Rockström, M. C. Öhman, P. Shyamsundar, W. Steffen, G. Glaser, N. Kanie and I. Noble (2013), 'Policy. Sustainable development goals for people and planet', Nature, 495 (7441), 305–07

Hartig, J., E. Klieme and D. Rauch (2007) 'The Concept of Competence in Educational Contexts', in Hartig, J., E. Klieme and D. Leutner (eds), Assessment of competencies in educational contexts, Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe & Huber, pp. 3–22

Hesselbarth, C. and S. Schaltegger (2014), 'Educating change agents for sustainability – learnings from the first sustainability management master of business administration', Journal of Cleaner Production, 62, 24–36

Hockerts, K. and R. Wüstenhagen (2010), 'Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids – Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship', Journal of Business Venturing, 25 (5), 481–92

Kao, R. W. (1993), 'Defining Entrepreneurship. Past, Present and?', Creativity and Innovation Management, 2 (1), 69–70

Leach, M., K. Raworth and J. Rockström (2013) 'Between social and planetary boundaries: Navigating pathways in the safe and just space for humanity', in UN Educational, S.a.C.O. and International Social Science Council (eds), World Social Science Report 2013: Changing Global Environments, Paris: OECD Publishing and UNESCO Publishing, pp. 84–89

Mayring, P. (2014), 'Qualitative Content Analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution', available at http://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/39517, accessed 19 December 2017

McMullen, J. S. and D. A. Shepherd (2006), 'Entrepreneurial Action and the Role Of Uncertainty In The Theory Of The Entrepreneur', Academy of Management Review, 31 (1), 132–52

Moberg, K., L. Vestergaard, A. Fayolle, D. Redford, T. Cooney, S. Singer, K. Sailer and D. Filip (2014), How to assess and evaluate the influence of entrepreneurship education: A report of the ASTEE project with a user guide to the tools, Odense: The Danish Foundation for Entrepreneurship – Young Enterprise

Nature Editorial (2003), 'Welcome to the Anthropocene', Nature, 424 (6950), 709

Ploum, L., V. Blok, T. Lans and O. Omta (2017), 'Toward a Validated Competence Framework for Sustainable Entrepreneurship', Organization & Environment, 34, 1–20

Raworth, K. (2012), 'A safe and just space for humanity: Can we live within the doughnut?', Oxfam Policy and Practice: Climate Change and Resilience, 8 (1), 1–26

Rockström, J., W. Steffen, K. Noone, A. Persson, F. S. Chapin, E. F. Lambin, T. M. Lenton, M. Scheffer, C. Folke, H. J. Schellnhuber, B. Nykvist, C. A. de Wit, T. Hughes, S. van der Leeuw, H. Rodhe, S. Sorlin, P. K. Snyder, R. Costanza, U. Svedin, M. Falkenmark, L. Karlberg, R. W. Corell, V. J. Fabry, J. Hansen, B. Walker, D. Liverman, K. Richardson, P. Crutzen and J. A. Foley (2009), 'A safe operating space for humanity', Nature, 461 (7263), 472–75

Rychen, D. S. and L. H. Salganik (2003), 'A holistic model of competence', in Rychen, D. S. and L. H. Salganik (eds), Key competencies for a successful life and well-functioning society, Cambridge: Hogrefe & Huber, pp. 41–62

Schaltegger, S. and M. Wagner (2011), 'Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation. Categories and interactions', Business Strategy and the Environment, 20 (4), 222–37

Shane, S. and S. Venkataraman (2000), 'The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research', Academy of Management Review, 25 (1), 217–26

Steffen, W., W. Broadgate, L. Deutsch, O. Gaffney and C. Ludwig (2015), 'The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration', The Anthropocene Review, 2 (1), 81–98

Svanström, M., F. J. Lozano-García and D. Rowe (2008), 'Learning outcomes for sustainable development in higher education', International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9 (3), 339–51

Ucbasaran, D., P. Westhead and M. Wright (2008), 'Opportunity Identification and Pursuit. Does an Entrepreneur's Human Capital Matter?', Small Business Economics, 30 (2), 153–73

Wassermann, S. (2015), 'Das qualitative Experteninterview', in Niederberger, M. (ed.), Methoden der Experten- und Stakeholdereinbindung in der sozialwissenschaftlichen Forschung, Wiesbaden: SpringerLink Bücher, Springer VS, pp. 51–67

Westhead, P., D. Ucbasaran and M. Wright (2005), 'Decisions, Actions, and Performance. Do Novice, Serial, and Portfolio Entrepreneurs Differ?', Journal of Small Business Management, 43 (4), 393–417

Weinert, F. E. (2001) 'Concept of Competence', in Rychen, D. S. and L. H. Salganik (eds), Defining and Selecting Key Competencies. Seattle: Hogrefe & Huber, pp. 45–66

Wiek, A., L. Withycombe and C. L. Redman (2011a), 'Key competencies in sustainability: a reference framework for academic program development', Sustainability Science, 6 (2), 203–18

Wiek, A., L. Withycombe, C. Redman and S. B. Mills (2011b), 'Moving Forward on Competence in Sustainability Research and Problem Solving', Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 53 (2), 3–13

To cite this paper please use the following details: Hagmaier, B. (2019), 'Sustainable Entrepreneurs as Change Agents: Relevant Key Competencies for Sustainability', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 12, Issue 1, https://reinventionjournal.org/article/view/431/389. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.