Gareth J Johnson, University of Warwick

Writing an academic article is something many students desire but common fears and concerns can prevent them from taking the next steps to publication success. This article offers insights from a journal’s Chief Editor aimed at early career and student authors considering publication, and hopes to enhance their publication experiences alongside avoiding some common mistakes. It explores how through spending time locating and evaluating suitable candidate journals from the outset, prospective authors can help avoid early rejections of their manuscript submissions. The article then proposes how authors, once writing is underway, can further increase their chances of a positive reception by reaching out to prospective editors. It illustrates that, as some form of peer-review is ubiquitous in academic publishing within quality research journals, authors should prepare to deal with reviews functionally, effectively and, where possible, dispassionately. Further, it suggests where rejection is encountered, authors should appreciate that other, alternative journals are likely to still be interested in publishing their work. Thus, through a lot of hard work, advice and attention to guidance from journals, and some common sense, any would-be author can achieve a publishable, quality academic article within a suitable research journal.

Writing an academic article is something that many students desire but often concerns or preconceptions can prevent them from taking the next steps to publication success. Maybe you are unsure about how the editorial process works or are concerned your writing is not ‘good’ enough to be published. Perhaps you have heard some horror stories about how journals operate and wonder if you could deal with ‘rejection’? These are all understandable obstacles that could prevent you from taking the steps from an article idea through manuscript submission to achieving a successful publication. The good news is every time you try publishing something – even if you are rejected straightaway as a ‘desk decline’ – will be a learning experience, making each subsequent attempt a tiny bit easier.[1] Hence, in this article, as an academic journal editor myself, I am going to offer some helpful insights for people considering publishing that will hopefully enhance and encourage their own authoring endeavours. A good starting question is ‘Why publish at all?’ Talk to academics and you will get a variety of answers. Some will say becoming recognised for their research or professional practice among their peers is essential. For others becoming part of the research conversation, offering counterpoints or clarifications to other scholars’ work is a crucial part of their research activities. Some may, perhaps ruefully, admit publishing is a means to an end given academic career opportunities rely on achieving a sufficiently healthy publication record. Even if you are not an academic, publishing an article can still be valuable addition for your CV, alongside generating a fair degree of personal satisfaction in becoming a published author.[2]

Figure 5: Achieving publication success…simply speaking.

Now, at the broadest level, getting published requires an uncomplicated transaction: you simply have to write something and be brave enough to submit it to a publisher[3] for consideration (Figure 1). What happens next will vary depending on where you have submitted your manuscript. Within this article, I will be focusing on academic research journals, collections of ‘essays’ by individual or groups of scholars that since the seventeenth century have been the primary route to disseminating and recording original contributions to knowledge.[4] Journals themselves were initially collated and disseminated by scholarly and learned societies, although in the past century, they have been increasingly run by highly profitable corporations. While this is an iniquitous situation, the advent and increasing ubiquity of online electronic ejournals since the 1990s onward have created a space and opportunity for scholars to regain some of their lost agency over publishing.[5]

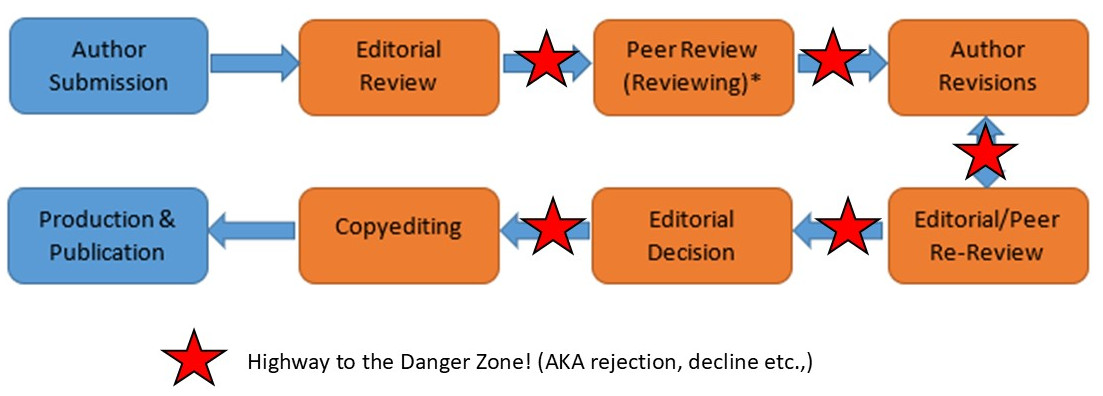

Today though, journal publishing is a heterogenous field, with publishers large and small offering literally hundreds of thousands of potential quality journal titles you could publish in. While the ‘quality bar’ you need to overcome to publish varies between individual titles, most function in a broadly analogous way: a manuscript is submitted by its author to a journal where an editor then checks to see if it is broadly in scope – that is potentially suitable – for their title. Assuming it is, the manuscript will undergo a process of review, likely followed by some revision recommendations for the author to accommodate. More review and revision may follow before the piece is accepted, formatted for publication (copyedited) and published (Figure 2). This sounds a simple, linear flow, but it is important to remember that at any point in this cycle, until an article is published, there is a potential that the journal will decide to reject the submission – that is decline to consider it further – which is why many authors approach any communication from an editor with trepidation.

Figure 2: Academic publishing simplified workflow and points of rejection.

Ensuring you are submitting a manuscript to a potentially suitable journal is why spending time firstly locating and evaluating potential candidates from the outset is crucial. There are many ways to approach this but initially considering journals in which you regularly read articles for study and research is a good first step. This ensures a strong familiarity with the style and types of articles they publish, helping to appreciate if your proposed article will likely resonate with other work in their pages. Having this sort of strong subject alignment can be key in overcoming any initial editorial scrutiny successfully. You may find it valuable to discuss potential journals with your colleagues, supervisors or tutors too, not least because they will be able to share some insights into those journals with whom they have had positive experiences themselves. You can also search the internet, databases or libraries for other journal inspirations, but you will need to spend more time evaluating them to fully appreciate if your work aligns sufficiently with their publishing interests.

Even if you already have a candidate journal in mind, being a reader is quite different from being an author. Finding and understanding what each journal requires of their authors is an essential next step, which is why it is important to find their ‘author guidance’ or selection policy information. Reading these alongside their recently published articles will help you form a strong impression of the ‘kind’ of journal you are dealing with, and if your work is likely to be welcomed.

Table 1: Evaluating candidate journals.

It can be useful to have a few questions in mind when evaluating any candidate journal (Table 1) to help you form a clear idea of their suitability. If the responses to these questions align with your interests, then this could be the right journal for you, and you should move ahead to prepare your manuscript for submission. Conversely, if not, do not worry, and move along to consider another potential title instead. By expending this small evaluative effort, you will undoubtably save yourself much heartache and frustration from a rapid manuscript rejection.[6] Once you do select a journal, keep their author guidance close. Failing to follow it carefully with your manuscript, especially when submitting work to any larger or prestigious journal has been the cause for many an early disappointment for an author. Try not to get weeded out simply by going over their word limits, for example. Incidentally, once you do have a manuscript under editorial consideration, you should not submit the same piece of work elsewhere – unless it is rejected! Doing so is considered very poor practice, with potential legal consequences – known generally as the Inglefinger Rule, after a past-editor of Nature.

Having located a strong candidate journal, your next steps should be to develop your article manuscript, keeping in mind any authorial guidance offered by the journal. A common mistake that less experienced authors make here is in not bringing their writing ‘A-game’ to the publication arena. Unlike an essay, dissertation or thesis, article manuscripts will be contrasted not with a marking scheme, but more abstractly against the standards of academics around the globe. This degree of ‘quality’ and ‘rigour’ is one reason why publishing in ‘high impact, prestigious’ journals is so much harder, because authors who are published in them are the ‘best of the best’. It is quite daunting and one reason why considering smaller, established, journals can be a more successful approach for your earliest articles. Even so, you will still be expected to meet – or exceed – their quality bar. Hence, never submit your first draft, as chances are it will be rejected out of hand without progressing on to formal review. The mantra ‘good enough to pass is not good enough to publish’ is worth keeping in mind!

While I am not going to deal with the ‘art’ of article writing here, however you approach it, always give yourself sufficient headspace to draft and proofread your manuscript.[7] Proofreading is more than a quick spellcheck and is a process best accomplished over a period of time. Trying to rapidly write a piece for journal submission means it is more likely you will miss simple errors by being too close to the text to objectively recognise aspects that need greater attention, clarity or refinement. Putting your manuscript aside for a week or two before re-reading and then extensively redrafting can really aid in making omissions or errors in your writing readily apparent. If you are less confident in proofreading, you might also find specialist advisers at your institution who can act as a ‘critical friend’ in advising on the weakness and strengths of your writing. If you are lucky enough to have colleagues who are more experienced authors willing to read and offer critical advice on your writing, then by all means share your manuscript with them. Where you might be considering writing for a wider audience than your own disciplinary peers – for example, in a cross or interdisciplinary journal – then it is a good idea to share your work with someone whose subject specialism differs from your own. They will be readily able to identify concerning aspects that a subject peer might miss. Likewise, recall any earlier feedback you have had from tutors – or journals – on your writing, paying particular attention to addressing any areas of recognised personal weakness.[8]

Creating an article from a past piece of ‘unpublished’ work – an essay or dissertation chapter, for example – is an approach many first-time authors adopt. However, if you read published articles and contrast them with your work, you will spot subtle differences between how these are structured and the ‘written voice’ employed. Hence, try and redraft your manuscript to more closely mirror the styles in successfully published pieces. Additionally, articles need to be able to exist as singular objects in their own right, meaning they need to contain any significant and relevant contextual information along with citing prior articles in support of areas of your own argumentation too. This also helps demonstrate your ‘alignment’ or ‘position’ within the previously published corpus of knowledge.[9] Another common mistake is creating an ‘overstuffed’ article – one that tries to cram too many ideas or core concepts into a single narrative. This kind of ‘bloat’ is a common error by inexperienced authors, who assume a ‘shotgun’ approach scattering ideas and information throughout will win them greater plaudits. Conversely, the best academic articles deal with a singular argument, concept or discovery, and provide sufficient space to interrogate it to a deeper, scholarly degree. Articles are, for the most part, intended to be in-depth explorations, not surface examinations – although if you are writing certain kinds of pieces, such as a review article, then you can probably disregard this particular advice.[10]

Throughout all this drafting, proofing and redrafting, it is sage advice to keep your audiences in mind. While you may be primarily, and sensibly, addressing your text to the journal’s readership, remember reviewers and editors will read your manuscript too, so it is advisable to consider how they will react to it. This is where attention to a strong, informative and accurate title, which captures their attention alongside delineating what the article concerns, is invaluable. Likewise, an abstract that directly resonates with the article’s contents, suitably guiding readers through your key arguments, can pay dividends too. For many reviewers, a mismatch between title, abstract and article contents is often cited as a rationale for rejecting a manuscript. Consequently, spend time and attention finalising your title and abstract ahead of a submission as they may make the difference between an immediate desk decline or acceptance for further consideration. Generally, though, when considering audiences, the broader the audience you are writing for, the greater the clarity you will need to bring, as, especially for cross-disciplinary audiences, you will need to expand on common terminology and concepts. Finally, remember you are writing for a global audience, which means using colloquial terms, phrases or idiomatic phrases may confuse or confound some readers or reviewers.[11]

While your preparations and writing is underway, the time is also ripe to start making introductions and reaching out to prospective editors. I wrote earlier about selecting your journal but selecting your editor with care matters too. Editors are – you may be surprised to read – people too, and often very busy ones, and you may find establishing a strong and harmonious working relationship with them can start some time ahead of any manuscript’s submission. Chief editors also significantly influence the contents of their journals beyond what their selection policy might state, which includes the potential for any manuscript to progress to an article. Hence, making an informal, pre-submission approach can help in adjudging if they are the kind of person you can work with but also in establishing if their journal is likely to be a receptive destination for your piece. Never send unsolicited manuscripts though as they simply will not read them; instead outline some key aspects in a brief email (Table 2).

Table 2: Introductory letters to editors.

Who you are and where you are based |

|

Title |

What is the draft title of your manuscript |

Outline |

A short outline concerning what your manuscript is about and why it matters (e.g. relevance, currency, originality) |

Relevance |

Why this journal is the right destination (e.g. topic, selection policy, recent issues) |

Audience |

Who are the audience for it (e.g. this journal’s readership) |

Literature |

How it relates or aligns with past journal articles (e.g. compliments, challenges, expands) |

Timespan |

An idea of when the manuscript will be ready |

Do ensure that you always use the correct journal and editor names if you are writing to multiple candidate journals – editors can have thin skins about such aspects! Such an introduction though will enable any editor to quickly appreciate and explain if your manuscript stands a reasonable chance of being considered for review and potential publication. If the answer is no – and it may be more often than you like – or they do not respond at all, do not worry and simply move along to consider another candidate journal. However, if an editor makes a positive response, giving the impression they are genuinely interested in your work, get your draft proofed, polished and submitted as soon as possible. Surprisingly, while editors are often voraciously keen for quality, suitable articles, as time moves on, they may lose interest. So take care not to over-promise on when you can deliver a submission.

Table 3: Typical editorial manuscript scrutinisation criteria.

Is it acceptable in terms of style, word count and any formatting requirements?[12] |

|

Scope |

Is the subject closely aligned with the journal’s stated interests? |

Readability |

Does the manuscript make reasonable sense or is it riddled with typographical, grammatical and syntax errors? |

Coherence |

Does the manuscript make a coherent argument and draw conclusions supported by its premise and/or analysis? |

Originality |

Is the manuscript wholly original work? Are there any plagiarism concerns? |

Importance |

For leading journals only, how potentially ‘globally significant’ is the manuscript? |

Once you are ready and have checked that you have met all the journal’s requirements in their author guidance, and have submitted your manuscript for consideration, editors will scrutinise it for a number of key areas (Table 3). Notably, the significance of an article is something only a handful of the major research journals consider; smaller and especially scholar-led journals tend to be more accepting of quality work that is not necessarily ‘epoch making’. If the editor finds the manuscript meets their key criteria, then hopefully they will proceed to accept your piece for further consideration where it will face its sternest test: peer-review.

While peer-review is often referred to as the ‘least-worst option’ editors have for maintaining quality in publication, it is ubiquitous throughout the academic publishing world and every quality research journal operates some measure of it. Exposing manuscripts to deeper scrutiny aids editors in ensuring only quality work will achieve formal publication in their pages. However, how any ‘reviewing process’ operates varies enormously across disciplines and individual titles, which is why familiarising yourself with how your candidate journal approaches it can be invaluable.[13] Reviewing also generally takes some considerable time to complete, so authors need to be patient, although contacting your editor every month or so can help you confirm that it is progressing. Nevertheless, likely your biggest concern as an author will be dealing with the review outcome, and typically there are two common outcomes: revisions (corrections) requested, or manuscript declined.

Should you receive revisions, read them carefully as the expectation is that authors will accommodate all comments in redrafting their text. You can, and should, challenge any aspects with your editor that you feel are not suitable to incorporate but will need to justify why. Simply refusing all corrections is not advisable as many editors will conclude you are not willing to work with them and will decline your manuscript from any further consideration! Should you find dealing with revision feedback daunting though, a good approach is to read it through once but then set it aside for a week or two and get on with life. Once you do return, simply treat the feedback as a ‘dispassionate to-do list’ of corrections and set to work addressing them. Alternatively, you might prefer to summarise feedback in your own words and work from this new, emotionally disconnected document instead. You might feel especially daunted if you have lengthy feedback to consider but this usually means reviewers perceived your article as worthy of them spending a long time considering, and in some respects can be taken as a marker of how much they value your potential paper. Remember though, do not fear any proposed revisions but rather employ them as a tool to improve your authorship: they are a critique on your writing not a judgement on you as a scholar, although some reviewers can be a little ‘terse’ in their phraseology.

As each article is as individual as its author, it is not practical to outline all possible revision requests that may be made of you, although I have touched on a number in this article. It is perhaps worth noting how many individual reviewers have their personal bête noire, those writing conventions or aspects that especially frustrate them and consequently may judge manuscripts containing such ‘errors’ more harshly than others (see Table 4 for examples). This is one reason why bringing your writing ‘A-game’ matters but also why considering past critiques of your written work while drafting your manuscript matters too. Although, reviewers are individuals with varied scholarly tastes, preconceptions and expectations and what annoys one reviewer may delight another – so prepare to be surprised and frustrated in equal measure!

Table 4: Example reviewer red flags.

Archaic, outmoded, irrelevant or insufficient citations |

Excessive self-citation by authors |

Extensive typographical/grammatical errors |

Good topic, poor match to journal’s stated goals |

Implicit/explicit use of AI/Large Language Models in writing |

Insufficient unified voice within multi-author articles |

Insufficient reader way markers or weak narrative flow |

Overly ‘chatty’ or ‘conversational’ narrative style |

Weak alignment between title/abstract and article contents |

Journals are a surprisingly time-sensitive production, and editors will normally set a deadline by which you are expected to return your amended manuscript, which you should always aim to meet. Where you are experiencing genuine life, work or study difficulties, be honest with your editor and explain at length any challenging circumstances you face. With appropriate justification, most editors will be sympathetic and willing to work with authors to identify a revised re-submission schedule. However, the worst ‘crime’ you can commit around deadlines is to simply ignore or fail to respond to messages from your editor: a rapid route to having your manuscript declined! If you are lucky, editors will warn you ahead of time before this happens, but if you persist in failing to meet any deadlines, it is normal to experience editorial rejection.[14]

At this stage, if you are fortunate, and have followed the revision feedback carefully, once you have resubmitted your revised manuscript, your editor may be in a position to accept it for publication. However, where major corrections were recommended for your work, you may find yourself going through additional rounds of review and revision before a final, and hopefully positive, decision can be made.

Conversely, what do you do if the editor says ‘No’ and rejects your article after review? If you look at the rejection rates, which most journals publish, you will see you are not alone, with many ‘top’ journals rejecting nearly all articles submitted to them. If you are rejected though, you are now free to consider a different journal, and so you should read any guidance from the title that declined you and use this to improve your manuscript for a subsequent journal.[15] Regretfully, it is common for authors to be considered and rejected by a sequence of journals before they find one willing to publish their article. Hopefully, each encounter will yield helpful feedback on improving your paper. So, try not to get disheartened but do appreciate, especially for first-time authors, getting that first article to publication can be a long-term effort. Eventually though, if you have a credible idea and are willing to work on improving your manuscript, you will achieve publication.

Congratulations! With any luck, and a lot of hard work, and drawing on the advice in this article, you are now on your way to becoming a published author. Naturally, while publishing might feel like an endpoint, it is actually the start rather than the conclusion of the journey. For example, since so many articles are published annually, drawing attention and promoting it via social media channels is an essential next step. LinkedIn, given its ‘business’ context, can be helpful here, but whichever routes you chose can help significantly raise awareness and increase any potential readership along with any citations your published work can gain. However, having made your contribution to scholarly discourse, you may even want to start thinking about another article. Continuing the conversation like this can be a powerful route to increasing readership of the original piece, alongside the career-enhancing benefits that establishing a ‘publication record’ creates. My hope is that this article has perhaps offered some insight into the often-labyrinthine world of academic publishing. If nothing else, I would suggest that having gone through the experience at least once, each subsequent publication effort should not feel half so daunting!

This article is based on a talk delivered by the author at the Leeds Art University, March 2025, to whom thanks is noted. Additionally, the author would like to acknowledge the warm invitation from the editorial team at Reinvention to submit this piece for their title. The author wishes to also acknowledge the support of Institute of Advanced Study, University of Warwick in providing funding in support of this work.

Dr Johnson has been Editor-in-Chief of the Exchanges journal since 2018, having previously completed a doctorate in Culture, Media and Social Theory focussing on the academic adoption of open publication practices. He also holds higher qualifications in biomedical technology, information management and research practice. He has published in excess of 200 articles, conference papers and reviews and book chapters. The Exchanges journal itself (ISSN 2053-9665) is an open-access, interdisciplinary title, published since 2013 and primarily run by and for early career researchers. It is hosted and funded by the Institute of Advanced Study at the University of Warwick.

Figure 1: Achieving publication success…simply speaking.

Figure 2: Academic publishing simplified workflow and points of rejection.

Table 1: Evaluating candidate journals.

Table 2: Introductory letters to editors.

Table 3: Typical editorial manuscript scrutinisation criteria.

Table 4: Example reviewer red flags.

Becker, H. S. (2020), Writing for Social Scientists (3rd edn), Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Eve, M. (2014), Open Access and the Humanities: Contexts, Controversies and the Future, Cambridge: CUP.

Indy, (2022), ‘How to write and sell your articles to a newspaper or magazine’, IndyUniversity, available at https://weareindy.com/blog/how-to-write-and-sell-your-articles-to-a-newspaper-or-magazine, accessed 1 April 2025.

Johnson, G. J., (2017), ‘Through struggle and indifference: The UK academy’s engagement with the open intellectual commons’, PhD thesis, Nottingham Trent University.

Johnson, G. J., C. Tzanakou and I. Ionescu (2018), ‘An introduction to peer review’, Coventry: PLOTINA, available at https://www.plotina.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Introduction-to-Peer-Review-Guide.pdf, accessed 1 April 2025.

Leaman, G. (2019), ‘Predatory practices and standard procedures in scholarly journal publishing’, Association for Practical and Professional Ethics, available at https://www.academia.edu/38583373/Predatory_Practices_and_Standard_Procedures_in_Scholarly_Journal_Publishing, accessed 1 April 2025.

Michael, J. (2024), ‘How to successfully pitch an article to a magazine (and get published)’, JornoPortfolio, available at https://www.journoportfolio.com/blog/how-to-successfully-pitch-an-article-to-a-magazine-and-get-published/, accessed 1 April 2025.

Suber, P. (2012), Open Access. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sword, H. (2019), Air & Light & Time & Space. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Think-Check-Submit (2025), Journals Checklist, available at https://thinkchecksubmit.org/journals/, accessed 1 April 2025.

As an author myself, I know that these were exactly the thoughts and concerns running through my head when I approached my earliest publications. While the apprehension of ‘Will they like it enough?’ never entirely goes away, it does become easier to handle with each attempt. ↑

This aspect of being published, I am happy to report, is an element that most people continue to enjoy even after they’ve published dozens of articles. ↑

In this article, ‘publisher’ is being used to generically refer to a variety of routes to formal publication: journal submissions, book chapters or books included. Although, my focus is primarily on journal articles, much of the advice offered applies to approaching any ‘academic publisher’. ↑

This article mainly deals with being published for an academic and student readership, rather than wider public consumption in magazines and popular books. Hence, while a lot of the advice here can be considered transferable, there are some distinct differences that you’d be advised to find out more about, if this is your goal. (See for example Michael, 2024; Indy, 2022). Incidentally, publishing academic works is generally unpaid – about which there is much discussion in the literature! ↑

I won’t belabour this point, but if you are interested in reading more, works by Eve (2014), Suber (2012) and even my own thesis (Johnson, 2017) are good introductions to the debates and arguments around the ‘commodification’ and ‘liberation’ of academic publishing from corporate hands. ↑

An excellent, and lengthier, assessment model for candidate journals can be found on the Think-Check-Submit (2025) site. This is especially useful when assessing any journal title that you suspect may be fraudulent or simply seeking to profit off your publication activities – so called ‘predatory’ or ‘trash’ journals (see also Leaman, 2019). ↑

There’s a couple of excellent books on the subject I would commend to you as a primer for writing stronger articles (Becker, 2020; Sword, 2019). ↑

We all have them – mine I’ve been told are apparently hiding the most exciting article elements in the middle of paragraphs! Or possibly in endnotes… ↑

A pro tip here is to always cite a few articles from your candidate journal – many editors will be looking for this as a guide to establishing your paper’s alignment or relationship with their title’s interests. ↑

Review articles purposefully appraise a field or its associated literature and offer an over-arching narrative appraisal. Hence, while they may be broader in scope, they still need to offer a strong singular insight or coherent narrative in order to make the piece coalesce into a publishable work. ↑

Unless, naturally, your article concerns the use of slang terms or colloquial language – in which case carry on but do remember to unpick and contextualise any phrases used all the same. Not everyone shares the same cultural context. ↑

Many journals expect you to use their submission template, so take care to check if this is expected. Any unformatted articles likely will receive a desk rejection in these cases. ↑

There isn’t space to explore the varieties, or alternatives, to peer-review here. Suffice to say there are many journals who experiment, to varying degrees of success, with alternative models such as post-publication or open review, for example. These can be more – or less – daunting to some authors, so choose your journal and its reviewing model with care. A piece I wrote with some colleagues does provide an excellent primer to the varying models of peer-review, should you be interested in learning more (Johnson et al., 2018). ↑

Asking for an extension on or after the deadline is considered poor academic practice, and you would be advised to consult your editor at least a week or two in advance of it. However, editors are under no obligation to be flexible and may simply mark your paper to be rejected if you cannot meet their original deadline. ↑

Remember to check the new candidate journal’s author guidelines as there will be subtle differences in terms of format, length and layout of your manuscript. It is rare to simply be able to send exactly the same document to another journal for consideration. ↑

To cite this paper please use the following details: Johnson, G.J. (2025), 'Breaking into Academic Publishing: Creating a credible, quality and publishable article', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 18, Issue 1, https://reinventionjournal.org/index.php/reinvention/article/view/1897. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities, please let us know by emailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.

https://doi.org/10.31273/reinvention.v18i1.1897, ISSN 1755-7429 © 2025, contact reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk. Published by the Institute for Advanced Teaching and Learning, University of Warwick. This is an open access article under the CC-BY licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)