Amy Parnell, University of Warwick

Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) are primarily spread through sexual activity. In recent years, STIs have been on the rise globally. In the United States, chlamydia and gonorrhoea are the most prevalent bacterial STIs and have been for the past decade. Both these infections infect the same tissues, have similar modes of transmission and clinical presentations, and can be treated by the same antibiotics. Yet, the epidemiology and forecasts appear to be different. This paper identifies vulnerable populations specific to gonorrhoea and chlamydia and assesses factors that are likely driving these disparities. Publicly available surveillance data from The Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was examined to identify vulnerable populations for both diseases. These findings show that there are sex-specific differences in risk of gonorrhoea and chlamydia, and that young females carry an increased risk of both. Also, there is an increased risk of both infections among the Black/African American population. Understanding risk and risk-drivers is essential to targeting these vulnerable populations for the interest of public health.

Keywords: Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs); Gonorrhoea; Chlamydia; Risk; Sex; Adolescents; Ethnic Minorities.

The United States is experiencing a rise in sexually transmitted infections (STIs), reaching an epidemic status, and posing a significant public health threat (Nelson et al., 2021). For the past decade, chlamydia and gonorrhoea have remained the most prevalent STIs in the USA, with 1,649,716 and 648,056 cases reported in 2022, respectively (Nelson et al., 2021).

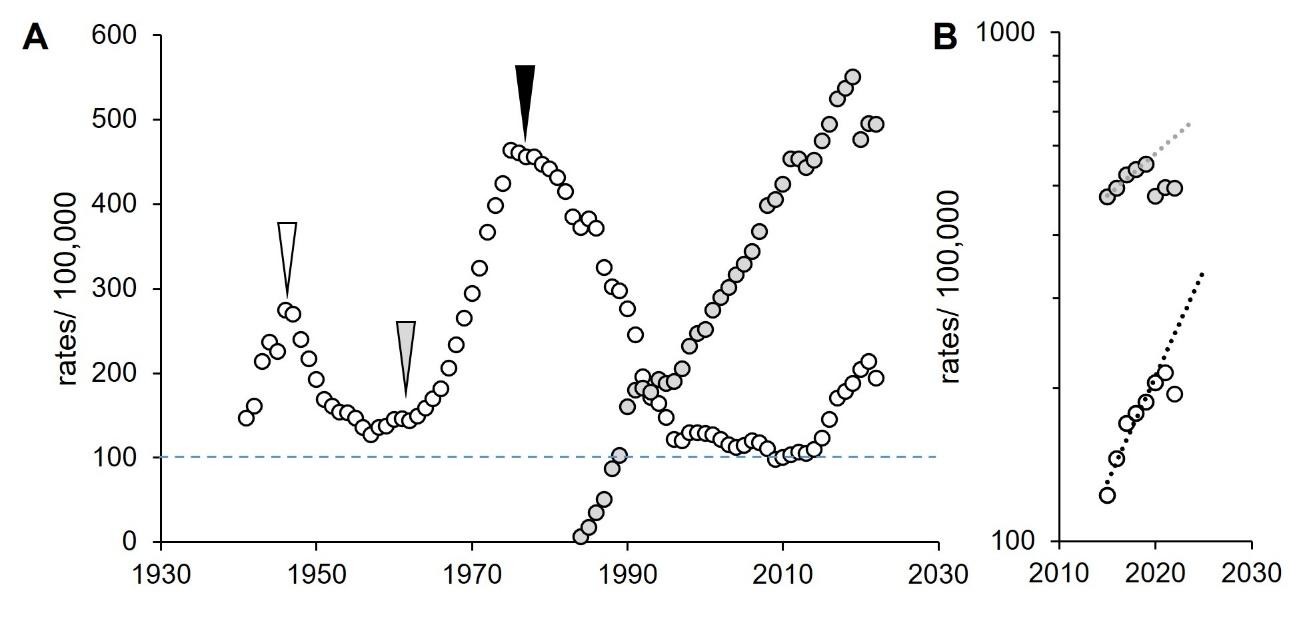

Rates of infection are dependent on historical events (Figure 1A).

Figure 1: Rates of gonorrhoea and chlamydia, USA 1941–2022. A. Incidence. White, gonorrhoea; grey, chlamydia. White, arrowhead, introduction of penicillin (Hook and Kirkcaldy, 2018); grey arrowhead, start of the free love and the hippie movement (Goldman, 1998; Johnson Lewis, 2019); black arrowhead, impact of condoms during HIV/AIDS epidemic (Kershaw, 2018; Boti Sidamo et al., 2021). Blue dashed line, threshold resistant to public health interventions. B. Future projections. Dotted lines, exponential extrapolations. Data from CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/sti-statistics/datavis/table-sticasesrates.html.

In recent years, rates of reported chlamydia and gonorrhoea in the USA have risen (CDC, 2024a). In 2022, the rates of reported cases of chlamydia were more than double that of gonorrhoea (Figure 1B) (CDC, 2024a). Curiously, they infect the same tissues, have similar modes of transmission and clinical presentations, and can be treated by the same antibiotics (CDC, 2021b; CDC, 2024a; Quillin and Seifert, 2018). Yet, the epidemiology and forecasts appear to be different. Considering the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on reporting, estimates were measured prior to the pandemic; these forecasts presented chlamydia doubling every 18 years and gonorrhoea doubling every 7 years (Figure 1B) (Sentís et al., 2021). This strongly suggests that transmission of these infections is driven by different populations. The aim of this project was to identify the risk groups and to explore key determinants that are driving these differences, such as biological, behavioural, cultural and social factors.

Transmission of gonorrhoea is highly efficient from males to their sexual partners through ejaculates as N. gonorrhoeae attaches to sperm (James-Holmquest et al., 1974). However, the efficiency of transmission from females to their partners remains unclear (Ketterer et al., 2016). Chlamydia transmission can occur during contact with infected genitalia, regardless of ejaculation (NHS, 2017).

Clinical manifestations of gonorrhoea and chlamydia are similar but often go unnoticed (Quillin and Seifert, 2018). Typically, symptoms are more apparent in males, such as dysuria and discharge from the penis, whereas females are more likely to experience inconspicuous symptoms, such as vaginal discharge, which can be mistaken for hormonal fluctuations and typical variability (Quillin and Seifert, 2018).

Timely treatment is important to reduce the severity of sequela and prevent further transmission (NHS, 2017). Importantly, if left untreated, chlamydia and gonorrhoea can result in PID, ectopic pregnancies and irreversible infertility in females and urethritis, epididymitis and proctocolitis in males (Jennings and Krywko, 2023; Stamm et al., 1984).

Thus far, there are no studies that include recent data released by the CDC that explore the US population. To improve sexual health, we must understand both distinct and common influences on risk and identify populations that are disproportionately at risk of these infections so we can consider public health interventions to target the populations that are disproportionately affected.

Datasets were from the Sexually Transmitted Infections Surveillance Report, published by The Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), https://www.cdc.gov/sti-statistics/data-vis/index.html.

The CDC surveillance data includes unrecorded sex, similarly unknown age and ethnicity. Since this data is uninterpretable, it was redacted for analysis. Multiracial data is counterintuitive due to the absence of details within this population, making it challenging to explore the social determinants affecting risk in this population.

Expected values considered the null hypothesis; there is no proportionate difference in sex of the population and observed number of STI diagnoses and these values were calculated from the proportion of the population (using US census data) (Duffin, 2022; BMJ, 2019). When observed frequencies were compared with expected frequencies of a single variable – for example, sex – a ꭓ2 Goodness of Fit test was used. An example calculation from 2017 is shown in Table 1. The gender ratio in the USA has remained steady since 2013 so the same ratio was used for analyses (Duffin, 2022).

When examining the relationship between two independent variables, such as sex and age, comparisons were made using a ꭓ2 contingency test (BMJ, 2019). Expected values were derived from ꭓ2 contingency considerations and calculated using the proportion of ethnicity (using US census data) and observed cases (BMJ, 2019). Risk groups, those with proportionately more or fewer cases than expected, were identified by the largest contribution to the ꭓ2 value (‘splitting’ of ꭓ2) (BMJ, 2019). Methods are described in full in BMJ Statistics at square one (BMJ, 2019). A worked example calculation from 2017 is shown in Table 2. Calculation outputs are shown in Table 3.

Table 1: Testing incidence of gonorrhoea in 2017.

sex |

o a |

e b |

o-e |

(o-e)2 |

(o-e)2/e |

|

Male |

321,963 |

274328.995 |

47,634 |

2268998413 |

8271.085 |

|

Female |

232,461 |

280095.005 |

-47,634 |

2268998413 |

8100.817 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

16371.9 |

χ2 |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

df c |

0 |

P d |

a observed cases; b expected cases (proportions from US census in 2010); c degrees of freedom; d probability value.

Table 2: Testing incidence of gonorrhoea in 2017.

|

o a |

o |

e b |

e |

||||||

Age |

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|||||

0–4 |

|

56 |

144 |

116.1432 |

83.85676 |

|||||

5–9 |

|

19 |

90 |

63.29807 |

45.70193 |

|||||

10–14 |

|

507 |

2,212 |

1578.967 |

1140.033 |

|||||

15–19 |

|

34918 |

57573 |

53711.02 |

38779.98 |

|||||

20–24 |

|

81036 |

74578 |

90367.57 |

65246.43 |

|||||

24–29 |

|

75123 |

46577 |

70673.16 |

51026.84 |

|||||

30–34 |

|

47342 |

24157 |

41520.63 |

29978.37 |

|||||

35–39 |

|

30277 |

13448 |

25391.82 |

18333.18 |

|||||

40–44 |

|

17753 |

6331 |

13985.97 |

10098.03 |

|||||

45–54 |

|

23803 |

5580 |

17063.18 |

12319.82 |

|||||

55–64 |

|

9311 |

1538 |

6300.19 |

4548.81 |

|||||

65+ |

|

1818 |

233 |

1191.049 |

859.9511 |

|||||

Total |

|

321963 |

232461 |

321,963 |

232,461 |

|||||

o-e |

o-e |

(o-e)2 |

|

(o-e)2 |

(o-e)2/e |

|

|

|

||

Male |

Female |

Male |

|

Female |

Male |

Female |

SUM |

|

||

-60.14324 |

60.14324 |

3617.209384 |

|

3617.209384 |

31.1 |

43.1 |

74.3 |

|

||

-44.29807 |

44.29807 |

1962.31866 |

|

1962.31866 |

31.0 |

42.9 |

73.9 |

|

||

-1071.967 |

1071.967 |

1149114.011 |

|

1149114.011 |

727.8 |

1008.0 |

1735.7 |

|

||

-18793.02 |

18793.02 |

353177687.5 |

|

353177687.5 |

6575.5 |

9107.2 |

15682.7 |

|

||

-9331.571 |

9331.571 |

87078220.62 |

|

87078220.62 |

963.6 |

1334.6 |

2298.2 |

|

||

4449.838 |

-4449.84 |

19801059.33 |

|

19801059.33 |

280.2 |

388.1 |

668.2 |

|

||

5821.372 |

-5821.37 |

33888374.51 |

|

33888374.51 |

816.2 |

1130.4 |

1946.6 |

|

||

4885.184 |

-4885.18 |

23865023.05 |

|

23865023.05 |

939.9 |

1301.7 |

2241.6 |

|

||

3767.031 |

-3767.03 |

14190522.35 |

|

14190522.35 |

1014.6 |

1405.3 |

2419.9 |

|

||

6739.816 |

-6739.82 |

45425117.21 |

|

45425117.21 |

2662.2 |

3687.2 |

6349.3 |

|

||

3010.81 |

-3010.81 |

9064976.352 |

|

9064976.352 |

1438.8 |

1992.8 |

3431.7 |

|

||

626.9511 |

-626.951 |

393067.6418 |

|

393067.6418 |

330.0 |

457.1 |

787.1 |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

37709 |

χ2 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

df c |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

P d |

|||

a observed cases; b expected cases (proportions from US census in 2010); c degrees of freedom; d probability value.

Table 3: Chi-squared test calculation outputs.

Sex-specific differences |

|||||||||

Gonorrhoea |

Chlamydia |

||||||||

Year |

ꭓ2 |

N a |

df c |

P d |

Year |

ꭓ2 |

N a |

df c |

P d |

2017 |

16371.9 |

554424 |

1 |

0 |

2017 |

166137.9 |

1703956 |

1 |

0 |

2018 |

19435.8 |

582167 |

1 |

0 |

2018 |

151787 |

1753474 |

1 |

0 |

2019 |

21333.9 |

614640 |

1 |

0 |

2019 |

136797.7 |

1800973 |

1 |

0 |

2020 |

15325.1 |

675432 |

1 |

0 |

2020 |

135244.4 |

1571770 |

1 |

0 |

2021 |

20208.4 |

702756 |

1 |

0 |

2021 |

121960.3 |

1630268 |

1 |

0 |

2022 |

31072.4 |

645594 |

1 |

0 |

2022 |

109668.3 |

1641143 |

1 |

0 |

Age-specific differences |

|||||||||

Gonorrhoea |

Chlamydia |

||||||||

Year |

ꭓ2 |

N a |

df c |

P d |

Year |

ꭓ2 |

N a |

df c |

P d |

2017 |

377709 |

554424 |

11 |

0 |

2017 |

74720 |

1703956 |

11 |

0 |

2018 |

38679 |

582167 |

11 |

0 |

2018 |

82023 |

1753474 |

11 |

0 |

2019 |

40388 |

614640 |

11 |

0 |

2019 |

85645 |

1800973 |

11 |

0 |

2020 |

38568 |

675432 |

11 |

0 |

2020 |

71411 |

1571770 |

11 |

0 |

2021 |

39799 |

704756 |

11 |

0 |

2021 |

77656 |

1630268 |

11 |

0 |

2022 |

38836 |

645594 |

11 |

0 |

2022 |

77837 |

1641143 |

11 |

0 |

Ethnicity-specific differences in 2022 |

|||||||||

Gonorrhoea |

Chlamydia |

||||||||

Sex |

ꭓ2 |

N a |

df c |

P d |

Sex |

ꭓ2 |

N a |

df c |

P d |

Males |

456346.9 |

303,311 |

6 |

0 |

Males |

405099.8 |

410560 |

6 |

0 |

Females |

224406.9 |

201122 |

6 |

0 |

Females |

658988.3 |

719612 |

6 |

0 |

Sex-specific differences between ethnicities in 2022 |

|||||||||

Gonorrhoea |

Chlamydia |

||||||||

Ethnicity |

ꭓ2 |

N a |

df c |

P d |

Ethnicity |

ꭓ2 |

N a |

df c |

P d |

B/AA |

15705 |

245961 |

11 |

0 |

B/AA |

18110 |

467246 |

11 |

0 |

White |

12020 |

142546 |

11 |

0 |

White |

31147 |

359737 |

11 |

0 |

Hisp/Lat |

6309 |

83524 |

11 |

0 |

Hisp/Lat |

13791 |

233536 |

11 |

0 |

Asian |

702 |

8053 |

11 |

0 |

Asian |

2024 |

20348 |

11 |

0 |

Multiracial |

1629 |

14142 |

11 |

0 |

Multiracial |

2877 |

28391 |

11 |

0 |

AI/AN |

166 |

9039 |

11 |

0 |

AI/AN |

276 |

17319 |

11 |

0 |

NH/PI |

73 |

1177 |

11 |

0 |

NH/PI |

170 |

3595 |

11 |

0 |

a observed cases; c degrees of freedom; d probability value.

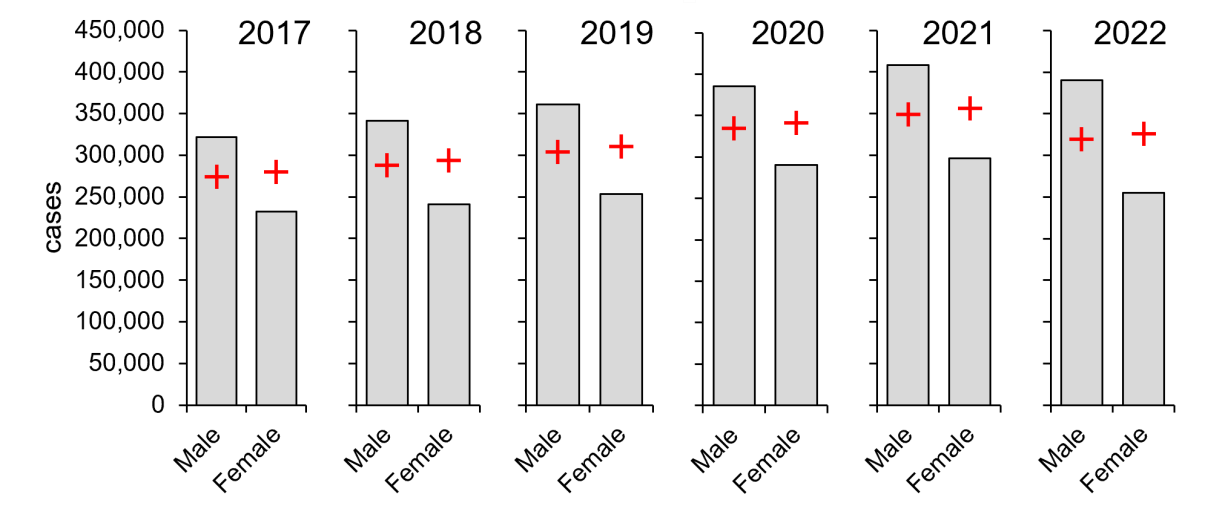

As a first step towards identifying high- and low-risk groups, diagnosed cases were separated by sex, and these observed numbers were compared with χ2 expectations based upon the proportion of males and females in US census records (see Table 1) (Duffin, 2022; U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). Over the past six years where data is available, males have consistently carried a greater burden of diagnosed gonorrhoea than females, with rates ranging from 28 per cent to 42 per cent higher and an average difference of 34 per cent (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Males carry a larger burden of diagnosed gonorrhoea (2017–2022). Columns, diagnoses; red crosses, expected values derived from the proportion of males and females in the US population (Duffin, 2022). Significance was determined by χ2 goodness of fit tests: an example calculation from 2017 is shown in Table 1. Data from CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/tables/15.htm.

In marked contrast, females have carried a consistently higher burden of diagnosed chlamydia than males over the same period, averaging 59 per cent higher with rates ranging from 54 per cent to 64 per cent (Figure 3). Thus, despite having the same transmission route and infecting the same tissues, there are sex-specific differences for the two infections. Of note, these are diagnosed cases, which may not reflect the true burden of disease due to factors such as avoidance of, or limited access to, regular sexual health screening.

Figure 3: Females carry a larger burden of diagnosed chlamydia (2017–2022). Columns, diagnoses; red crosses, expected values derived from χ2 considerations. Data from CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/tables/6.htm.

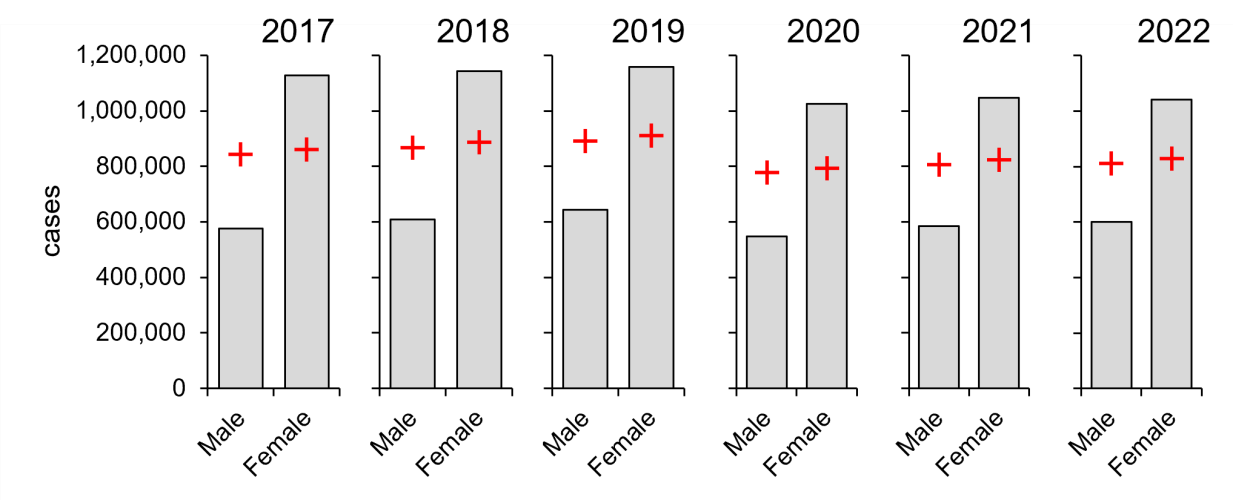

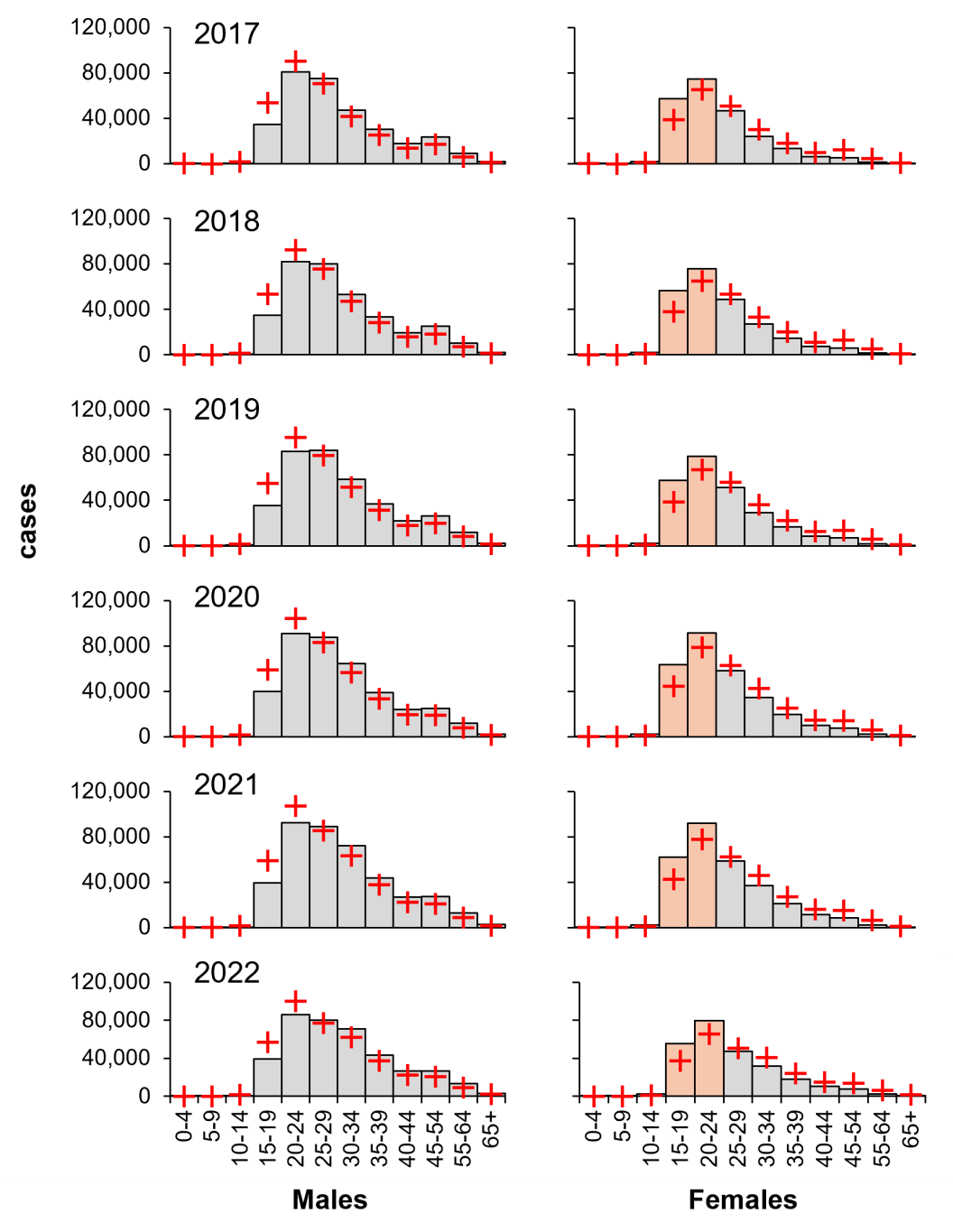

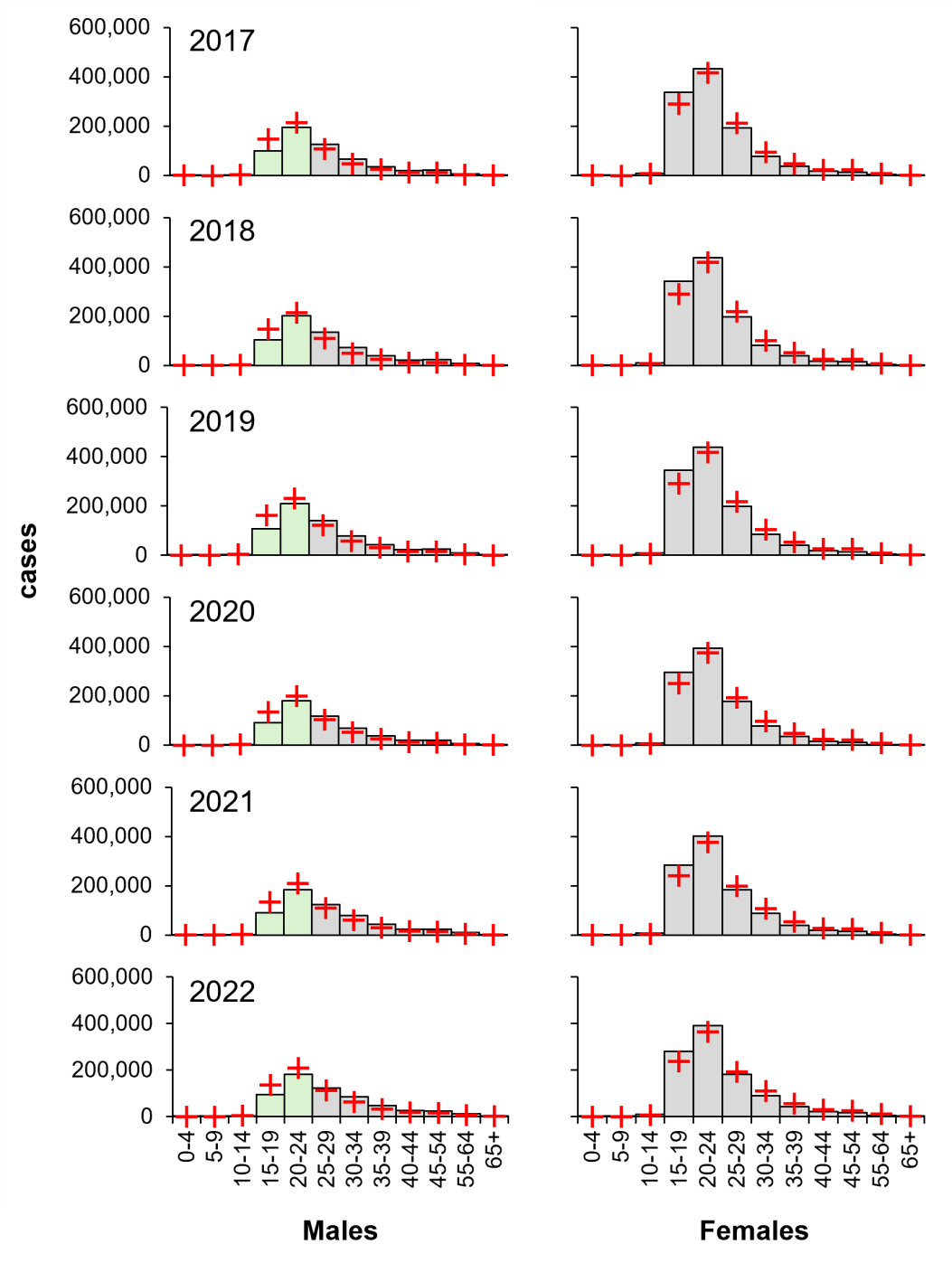

Having established the influence of sex on the burden of infection, the data was divided into age and sex, examining by χ2 contingency tests (see Table 2). Despite there being an average of 34 per cent greater burden of infection in males, young females (age 15–24) carry a high proportional risk and have done for the last six years (Figure 4). Notably, older males (age 45–54) also carry a high proportional risk, suggesting transmission from older males to young females.

Figure 4: Young females carry a larger proportional burden of diagnosed gonorrhoea (2017–2022). Columns, diagnoses; orange, high-risk female groups; red crosses, expected values derived from χ2 contingency considerations: an example calculation from 2017 is shown in Table 2. Data from CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/tables/15.htm.

Conversely, even though females carried an average of 59 per cent greater burden of diagnosed chlamydia, young males (age 15–24) have the lowest proportional risk of chlamydia and have done for the last six years (Figure 5), indicating that the burden of infection is age dependent.

Figure 5: Young males carry the lowest proportional burden of diagnosed chlamydia (2017–2022). Columns, diagnoses; green, low-risk male groups; red crosses, expected values derived from χ2 contingency considerations. Data from CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/tables/6.htm.

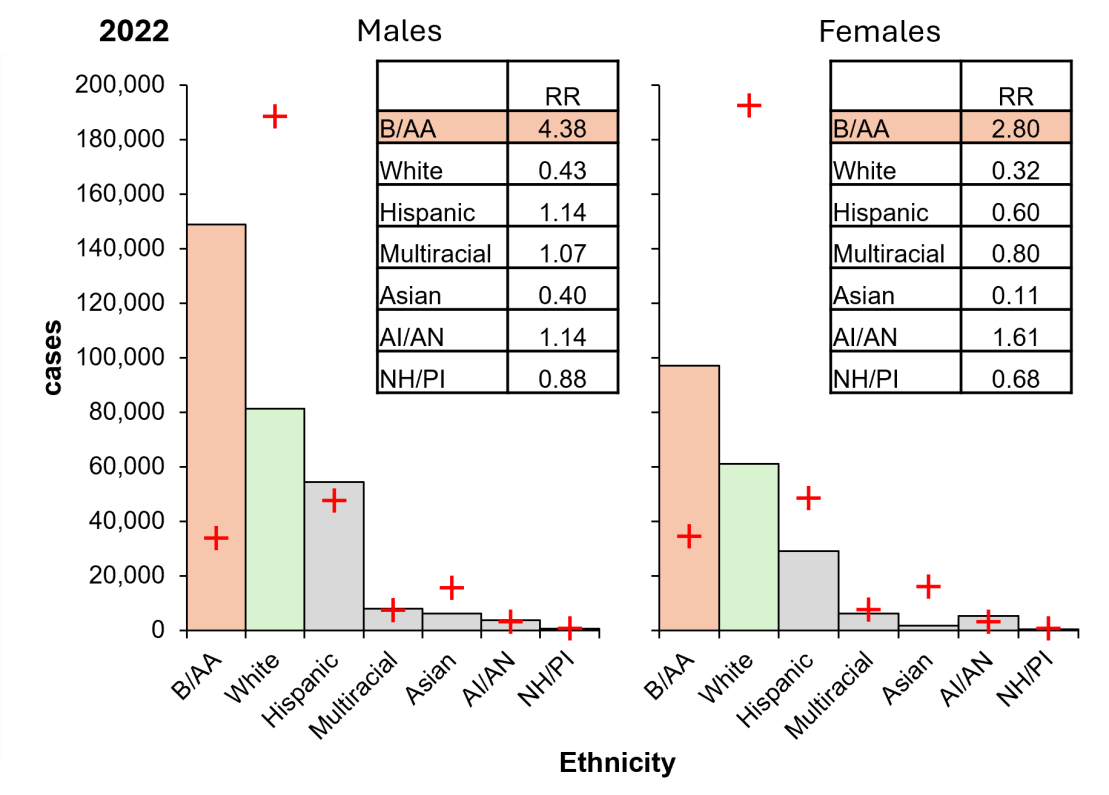

Having identified the impact of age and sex, the impact of ethnicity on risk was investigated by χ2 goodness of fit. The Black/African American population were revealed to have a proportionately high risk of gonorrhoea, and the White population are proportionately low risk (Figure 6). Specifically, Black/African American males are ten times more likely to be diagnosed with gonorrhoea than White males, while Black/African American females are almost nine times more likely than White females.

Females were also identified as lower relative risk of gonorrhoea compared to their male counterparts, except in the American Indian/Alaska Native population. Despite the burden of diagnosis being higher among the Black/African American population, there is a notable shift in the Hispanic/Latino population, where Hispanic/Latino males are at a proportionately higher risk of infection and females at a proportionately low risk. The Asian population have the lowest relative risk. American Indian/Alaska Native have a relatively high risk of infection.

Figure 6: The US Black/African American population carries a disproportionate burden of gonorrhoeal cases in 2022. Columns, diagnoses; orange, highest risk group; green, lowest risk group; crosses, expectation. Inset, RR, relative risk (observed/expected). B/AA, Black/African American; Hispanic, Hispanic/Latino; AI/AN, American Indian/Alaskan Native; NH/PI, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Data from CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/tables/16.htm.

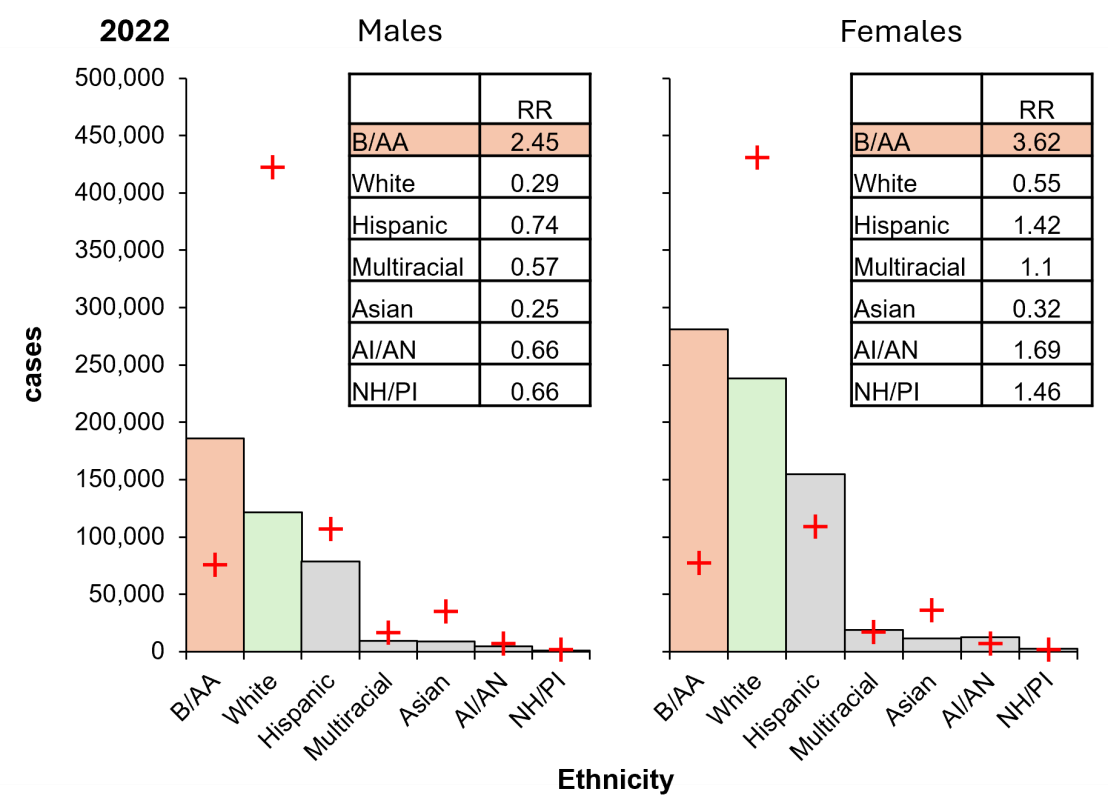

Like gonorrhoea infection, Black/African American population carry the highest proportional risk of chlamydia cases (Figure 7). Black/African American males are more than eight times as likely to be diagnosed with chlamydia, and females are over six times as likely, compared to their White counterparts. However, White males have the highest proportional contribution to χ2, carrying the lowest proportional risk. Remarkably, Hispanic/Latino females have a high proportional risk, and males have a low proportional risk, despite the inverse being observed for gonorrhoea. A similar trend was observed in the Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander population. Like gonorrhoeal infection, the Asian population are associated with low risk whereas American Indian/Alaska Native are associated with high risk.

While these results indicate that ethnicity influences the risk of these infections, social and cultural factors also play a role in these disparities.

Figure 7: The US Black/African American population carries a disproportionate burden of chlamydia cases in 2022. Columns, diagnoses; orange, highest risk group; green, lowest risk group; crosses, expectation. Inset, RR, relative risk (observed/expected). B/AA, Black/African American; Hispanic, Hispanic/Latino; AI/AN, American Indian/Alaskan Native; NH/PI, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Data from CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/tables/7.htm.

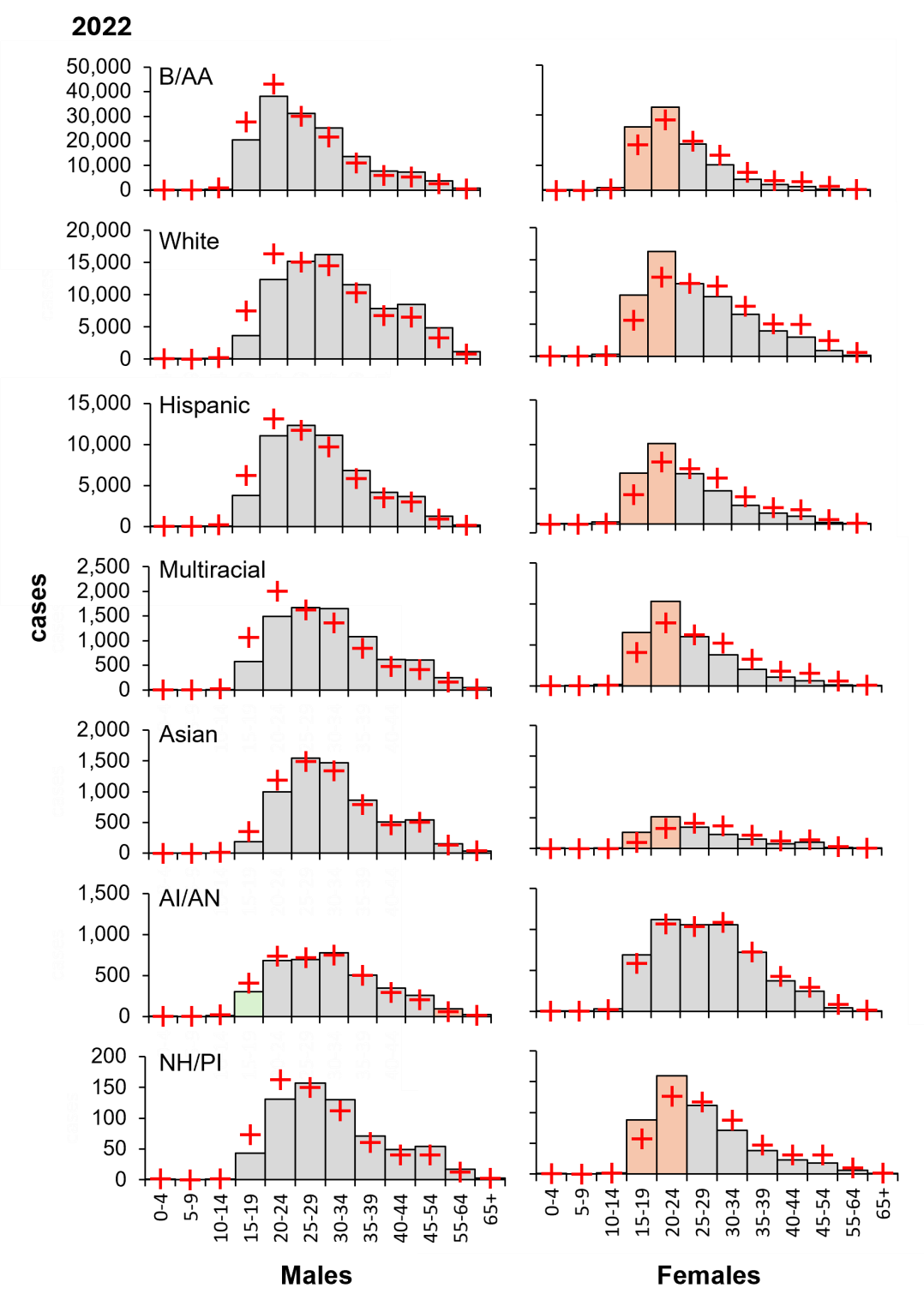

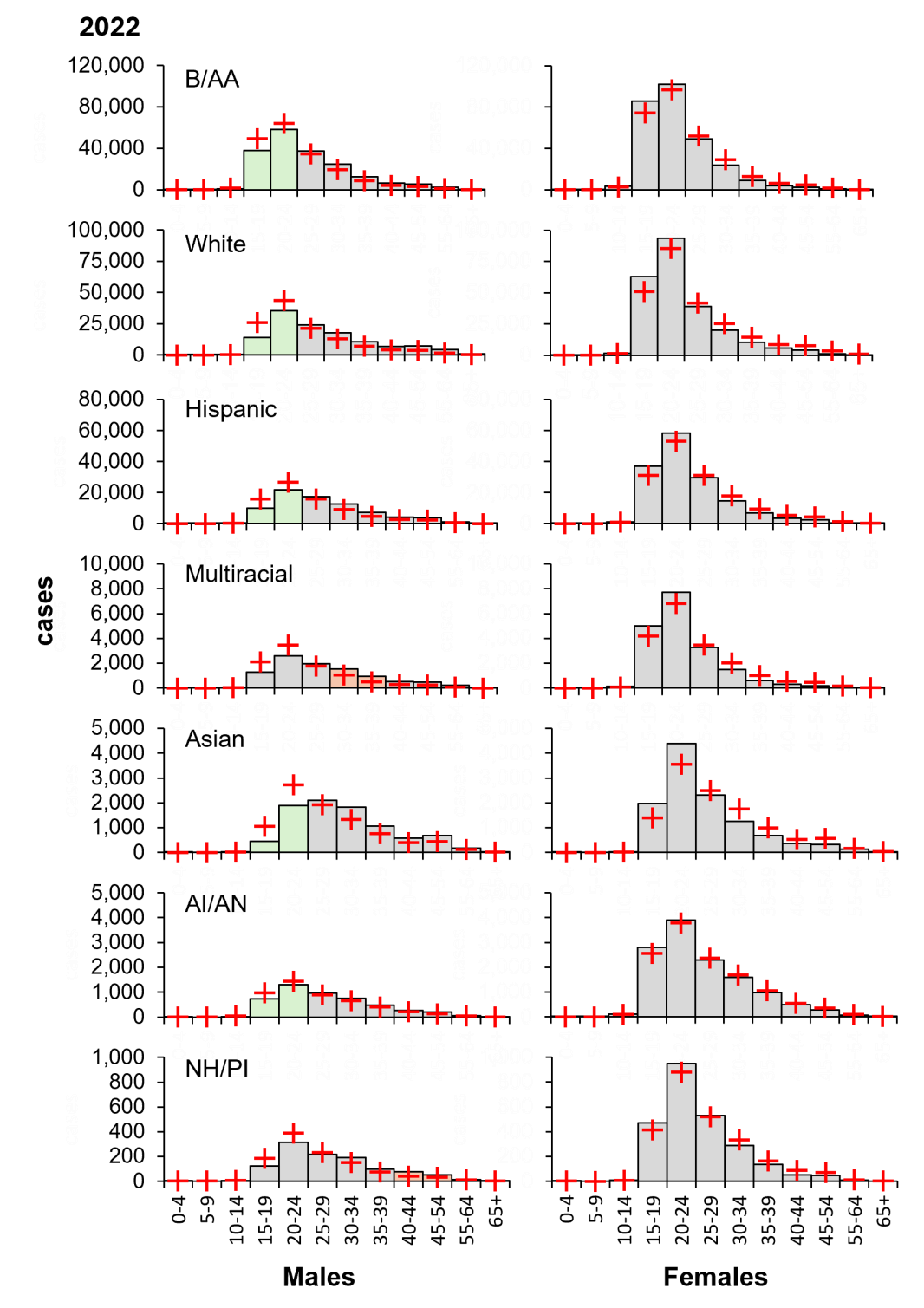

Next, the risks associated with age within ethnic groups was examined by χ2 contingency tests. Overall, risk groups were similar across ethnicities, with adolescent and young adult females (age 15–24) having the highest proportional risk of gonorrhoea (Figure 8). Interestingly, American Indian/Alaskan Native individuals formed a distinct risk group, with young adult males (aged 15–19) exhibiting a high proportional risk. This was attributed to underreporting, which may mask the true number of cases in this population. Nevertheless, the uniform risk across the three largest populations suggests factors, other than cultural, are driving infection.

Figure 8: Independent of ethnicity, young females carry a disproportionately high burden of gonorrhoeal cases in 2022. Columns, diagnoses; orange, highest risk group; green, lowest risk male groups; red crosses, expected values derived from χ2 contingency considerations. B/AA, Black/African American; Hispanic, Hispanic/Latino; AI/AN, American Indian/Alaskan Native; NH/PI, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Data from CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/tables/16.htm.

Similarly, risk groups for chlamydia are consistent across ethnicities. Notably, young males (age 15–24) have the lowest proportional risk of chlamydia (Figure 9). Distinct risk groups were identified in Multiracial and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander ethnicities, although this is likely justified by the relatively small population size.

Figure 9: Independent of ethnicity, young males carry a disproportionately low burden of chlamydia cases in 2022. Columns, diagnoses; orange, highest risk group; green, lowest risk male groups; red crosses, expected values derived from χ2 contingency considerations. B/AA, Black/African American; Hispanic, Hispanic/Latino; AI/AN, American Indian/Alaskan Native; NH/PI, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Data from CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/tables/7.htm.

Given that STIs are on the rise in the USA, I sought to identify risk groups and explore potential drivers of infection for gonorrhoea and chlamydia (Nelson et al., 2021). When comparing observed cases with ꭓ2 expectations, I noticed that there are different burdens of diagnosis between sexes and have been since 2017. Males carry the burden of gonorrhoea diagnosis and females carry the burden of chlamydia diagnosis.

It is recognised that females are biologically more susceptible to STIs due to the vulnerability of the vaginal membrane (Van Gerwen et al., 2022). The vaginal mucosa is thin and easily penetrated by an array of pathogens, including N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis (Van Gerwen et al., 2022). In tandem, there is an increased efficiency of transmission from males to females, compared to females to males (Hooper et al., 1978; Platt et al., 1983). Recent studies indicate that following a single sexual encounter exposing an individual to gonorrhoea, a female is 60–90 per cent likely to become infected whereas a male is only 20–30 per cent likely, due to a greater exposure in females due to pooled semen in the vagina in conjunction with trauma to vaginal tissue during intercourse (Platt et al., 1983; Hooper et al., 1978). In addition, females are more likely to carry less decision-making power over sexual relationships, which is associated with the ability to ensure consistent condom use (Ford and Lepkowski, 2004; Tschann et al., 2002). Therefore, females are more biologically susceptible and have less empowerment over protecting themselves, which may partly explain the increased risk observed in females for chlamydia.

Biological susceptibility does not explain the difference observed in gonorrhoea, where males carry the burden of diagnosis. Instead, the cryptic nature of these infections may explain this disparity (Quillin and Seifert, 2018). Both infections often go unnoticed, but chlamydia infection appears to be more inconspicuous. Chlamydia infection is asymptomatic in up to 70 per cent of females and 50 per cent of males while gonorrhoea is estimated to be 10 per cent of males and 50 per cent of females (NHS, 2019). This suggests that asymptomatic screening likely plays a substantial role in reported chlamydia (CDC, 2024b). In contrast, symptomatic testing, more common in males, is responsible for the majority of reported gonorrhoea cases. This concept was supported by a study associating sex with different health-seeking behaviours; specifically, young females are more engaged in health services, such as regular Pap testing, which link them to sexual health services (Knight et al., 2016). Hence, females are more likely to go for asymptomatic testing.

In marked contrast, young males practice self-monitoring of symptoms and tend to avoid formal diagnosis (Knight et al., 2016). When young males did access sexual health services, they did so reactively: after engaging in a high-risk sexual encounter or when experiencing symptoms (Knight et al., 2016). Taken together, the sex differences in cases of gonorrhoea and chlamydia can be explained by diverging health-seeking behaviours, such that females tend to be proactive so are more likely to detect asymptomatic infections, which are most common in chlamydia, while males tend to be reactive, seeking testing when they experience symptoms, which are more common in gonorrhoea (Knight et al., 2016).

Risk is also age dependent. I revealed that while males have an elevated overall risk of gonorrhoea, young females (aged 15–24) have a high proportional risk of infection. Biological susceptibility is partially responsible for the elevated risk in pubescent females due to increased cervical ectopy and a lower production of cervical mucus (Lee et al., 2006; Shannon and Klausner, 2019). Studies have shown the cervical ectopy is linked with increased risk of gonorrhoea and chlamydia infection (Kleppa et al., 2014). Young females also tend to have a lower production of cervical mucus, which plays a protective role against infection (Wong et al., 2004). Thus, if exposed to an STI, young females are more likely to get infected, which would explain the disparity in risk of gonorrhoea (Kleppa et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2006; Shannon and Klausner, 2019; Wong et al., 2004).

Additionally, behavioural factors, as highlighted in a pilot study, influence risk of STIs (Tzilos et al., 2020). Namely, alcohol consumption while at college was closely linked to engaging in condomless sex (Tzilos et al., 2020). Another study highlighted that young people are more likely to reduce or drop using condoms when in monogamous relationships, potentially exposing them to STIs (Brady et al., 2009).

Notably, this difference was not seen in young males (age 15–24), identified as proportionately low risk of gonorrhoea and chlamydia. However, these results seem paradoxical. In fact, according to current literature, all adolescents are at an increased risk of STIs (Maraynes et al., 2017; The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2022). I reasoned that reduced screening is masking true cases in the young male population (Maraynes et al., 2017).

In terms of behaviour, adolescents are typically more likely to engage in sexual activity associated with increased risk of STIs, such as concurrent partners and condomless sex, due to a developing prefrontal cortex (Shannon and Klausner, 2019).

Since my results are driven by Chi-squared expectation, risk groups are revealed if they deviate from the major population – in this case, White (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). When comparing ethnicities, it is clear there are considerable differences in relative risk of gonorrhoea and chlamydia. Black/African Americans are at elevated risk and Whites are proportionately low risk. I first explored the possibility of behavioural differences driving these diverging risks. A study discovered that Whites and Hispanics are more likely to engage in oral sex when compared to Black/African Americans (Auslander et al., 2009). The study also revealed that among this cohort, females who had experience of vaginal and oral sex were six times more likely to have a history of STIs, compared to those who had experience of vaginal sex only (Auslander et al., 2009). Another study supported these findings (Salazar et al., 2008). Therefore, despite Black/African American being more likely to participate in behaviour associated with low risk, they remain at increased risk. Alternatively, White females are more likely to engage in risk-associated behaviours yet remain low risk. This provides compelling evidence that risk is not determined solely by sexual practices (Auslander et al., 2009; Salazar et al., 2008).

The relative risk among the Asian population was lower than any other ethnic group. This is consistent with research that suggests that Asians are more conservative in sexual behaviours (Okazaki, 2002). Specifically, a cross-sectional questionnaire study revealed that Asian students reported sexual initiation at a later age compared to non-Asian students, a lower likelihood of having participated in oral sex and a lower number of lifetime sexual partners (Meston et al., 1996). Culturally, Asians value family and maintain traditional gender roles; hence, young people tend to abstain from sexual activity to avoid embarrassment and family disagreement (Okazaki, 2002). Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders share these family values and display a similarly low risk (Okazaki, 2002). Therefore, the observed risk is reflective of low-risk behaviours (Okazaki, 2002).

Of note, the Hispanic/Latino population displayed unique risk characteristics and sex was identified as a key determinant of risk. Hispanic/Latino males are low risk of chlamydia and Hispanic/Latino females are high risk. This is likely attributed to biological susceptibility and health-seeking behaviours previously discussed (Ford and Lepkowski, 2004; Hooper et al., 1978; Knight et al., 2016; Platt et al., 1983; Tschann et al., 2002).

Curiously, the risk of chlamydia is shifted as Hispanic/Latino males are high risk of gonorrhoea whereas Hispanic/Latino females are low risk. This strongly suggests that gonorrhoea and chlamydia infection are driven by different populations.

Next, I explored social factors that influence risk of gonorrhoea and chlamydia. In Black/African American communities, there is a smaller number of males compared to females (Adimora and Schoenbach, 2005). This restricts the variation in sexual partners and larger overlaps in sexual networks, which would facilitate the rapid transmission of STIs (Adimora and Schoenbach, 2005). There is also an increased prevalence of gonorrhoea and chlamydia in the population so, following each sexual encounter, there is a higher risk of infection (Adimora and Schoenbach, 2005). The CDC suggests that historical injustices in healthcare, employment and education is likely the driver of existing sexual health inequities (CDC, 2024b; Sutton et al., 2021).

Furthermore, there is an overrepresentation of Black/African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos living in poverty in the USA (Shrider, 2023). Unsurprisingly, low socioeconomic status is associated with high risk of STIs (Boskey, 2009). It has also been linked with inconsistent condom use (Davidoff-Gore et al., 2011). Exposure to poverty predisposes individuals to substance abuse, which increases risk of STIs (Hwang et al., 2000; Manhica et al., 2020). This suggests that socioeconomic factors have influenced the racial disparities in cases of gonorrhoea and chlamydia, particularly evident in the Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino populations (Hwang et al., 2000; Manhica et al., 2020). Nonetheless, these observations largely remained evident after adjusting for socioeconomic and other demographic variables (Zenilman, 2001). A similar discrepancy was identified in the UK where there is universal access to free healthcare (Zenilman, 2001). Hence, the disparity cannot be caused solely by a lack of access to sexual health services, but a reflection of health-seeking behaviours. I reasoned that injustices may deter ethnic minorities from accessing healthcare because of the anticipated discrimination from healthcare providers (Medical Institute for Sexual Health, 2024).

Similarly, historical mistreatment among Indigenous populations, as seen in the American Indian/Alaska Native population, has caused disproportionately high rates of poverty and limited access to sexual health services (Kirkcaldy et al., 2019). Limited access to healthcare services results in reduced condom use and reduced screening, all contributing to an increase in transmission (Sutton et al., 2021). Social isolation can amplify this effect due to a high prevalence of gonorrhoea and chlamydia in the sexual network, reinforcing transmission (CDC, 2024b).

Aside from the American Indian/Alaska Native population, risk groups are consistent across all ethnicities, with young females carrying a higher burden of diagnosis of gonorrhoea. I reasoned that biological susceptibility is largely responsible due to a uniform risk among young females, including populations that are associated with low-risk behaviours (Okazaki, 2002).

Georgetown Law Centre on Poverty and Inequality found that young Black females are viewed as more mature than their White peers (Epstein et al., 2017). Crucially, the concept of adultification can influence behaviours towards young Black females, exposing them to adult knowledge and conferring adult responsibilities (Burton, 2007). These misperceptions can leave young Black females vulnerable to sexual abuse and subsequent STIs (Crooks et al., 2019). Therefore, the elevated risk of gonorrhoea and chlamydia observed in young Black females may be in part a consequence of their adultification (Burton, 2007; Crooks et al., 2019; Epstein et al., 2017).

Among American Indian/Alaska Native there is little enhanced risk in young females; instead, young males carry a proportionately low risk of gonorrhoea. The literature suggests that high levels of underreporting in this population is masking true cases (Armenta et al., 2021). The literature suggests that risk is high due to engagement in risk-associated behaviours, poor awareness of STIs and prevention methods, and self-perception of low risk (Armenta et al., 2021). Barriers to accessing sexual health services include a lack of transportation in rural communities, stigma and a fear of disclosure (Armenta et al., 2021). Therefore, the observed risk among is likely a result of underreporting among the population (Armenta et al., 2021).

Corresponding with earlier results, young males have a uniform low risk of chlamydia. However, this may be due to underreporting as previously discussed, an alternative reason is indeed young males may not be as sexually active as they claim. Early studies found that there was evidence of a double standard, causing young males to overreport their sexual encounters and females to underreport (Eden and Others, 1995; Oliver and Sedikides, 1992; Sprecher et al., 1987); although there are no recent studies confirming this notion is still present (Gentry, 1998; Marks and Fraley, 2005; Milhausen and Herold, 1999). I speculate that the low risk of gonorrhoea and chlamydia seen in young males may be representative of true cases. Still, this would require further investigation.

First, my findings are based on surveillance data of confirmed cases. Therefore, it is possible that there are individuals not captured due to being unaware of their infection. Second, although the data shows that the Black/African American population carry a disproportionately high risk of gonorrhoea and chlamydia, the CDC generalise ethnicities, such that Black/African American includes both Black African American and Black Caribbean. In fact, surveillance data in the UK has revealed Black Caribbean having the highest burden of diagnosis, in marked contrast to Black Africans who carry a relatively low risk of STIs (Public Health England, 2021). Thus, surveillance distinguishing between ethnic groups is warranted. Similarly, the CDC does not report data on sexual orientation in the context of gonorrhoea or chlamydia, except by state. This would be beneficial as sexual orientation can assist in determining risk. Third, there is the risk of misclassification, particularly among American Indian/Alaska Native, who are commonly misidentified as White or Hispanic/Latino, potentially limiting reliability (Bertolli et al., 2007).

Despite these limitations, these findings highlight several important directions in this research field. (1) Gonorrhoea and chlamydia are influenced by sex differences due to biological susceptibility, varying health-seeking behaviours and transmission patterns in same-sex encounters. (2) Young females carry a disproportionately high risk of gonorrhoea and chlamydia due to increased biological susceptibility and risk-associated behaviour. (3) Ethnic disparities are apparent, emanating from social inequalities and pre-existing risk.

Overall, my research aligns with previous literature, confirming that age and racial disparities persist, with adolescents and ethnic minorities being at increased risk of chlamydia and gonorrhoea. These findings are unique as they take a holistic approach to analysing population-based data, rather than focusing exclusively on historically high-risk groups such as transgender individuals and sex workers. While these groups carry a significant infection burden, they constitute a relatively small proportion of the population. My research also contextualises the drivers of infection, exploring how sex, age and ethnicity influence risk. These insights can inform evidence-based public health interventions which target the most vulnerable populations. Consequently, this research provides a distinctive perspective on current vulnerability, aiding efforts to reduce the prevalence of these highly common sexually transmitted infections in the USA.

The author of this article is Amy Parnell, the University of Warwick. I would like to extend my deep thanks to Dr Robert Spooner who offered his expertise and support.

Table 1: Testing incidence of gonorrhoea in 2017.

Table 2: Testing incidence of gonorrhoea in 2017.

Table 3: Chi-squared test calculation outputs.

Figure 1: Rates of gonorrhoea and chlamydia, USA 1941–2022.

Figure 2: Males carry a larger burden of diagnosed gonorrhoea (2017–2022).

Figure 3: Females carry a larger burden of diagnosed chlamydia (2017–2022).

Figure 4: Young females carry a larger proportional burden of diagnosed gonorrhoea (2017–2022).

Figure 5: Young males carry the lowest proportional burden of diagnosed chlamydia (2017–2022).

Figure 6: The US Black/African American population carries a disproportionate burden of gonorrhoeal cases in 2022.

Figure 7: The US Black/African American population carries a disproportionate burden of chlamydia cases in 2022.

Figure 8: Independent of ethnicity, young females carry a disproportionately high burden of gonorrhoeal cases in 2022.

Figure 9: Independent of ethnicity, young males carry a disproportionately low burden of chlamydia cases in 2022.

Adimora, A. A. and V. J Schoenbach (2005), ‘Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections’, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 191 (s1), S115–S122, available at https://doi.org/10.1086/425280, accessed 27 May 2024.

Armenta, R. F., D. Kellogg, J. L. Montoya, R. Romero, S. Armao, D. Calac and T. L Gaines (2021), ‘There is a lot of practice in not thinking about that’: Structural, interpersonal, and individual level barriers to HIV/STI prevention among reservation based American Indians, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (7), 3566, available at https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073566, accessed 8 May 2024.

Auslander, B. A., F. M. Biro, P.A. Succop, M.B. Short, and S.L. Rosenthal (2009), ‘Racial/ethnic differences in patterns of sexual behavior and STI risk among sexually experienced adolescent girls’, Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 22 (1), 33–39, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2008.01.075, accessed 22 May 2024.

BMJ (2019), The chi squared tests | the BMJ. [online] BMJ.com, available at: https://bmjchicken.bmj.com/thebmj/about-bmj/resources-readers/publications/statistics-square-one/8-chisquared-tests, accessed 21 May 2024.

Boskey, E. (2009), ‘Socioeconomic status (SES) and STD risk,’ Verywell Health Online, available at: https://www.verywellhealth.com/socioeconomic-status-ses-3132909, accessed 27 May 2024.

Boti Sidamo, N., S. Hussen, T. Shibiru, M. Girma, M. Shegaze, A. Mersha, T. Fikadu, Z. Gebru, E. Andarge, M. Glagn, S. Gebeyehu, B. Oumer and G. Temesgen (2021), ‘Exploring barriers to effective implementation of public health measures for prevention and control of COVID-19 pandemic in Gamo zone of Southern Ethiopia: Using a modified Tanahashi model’, Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 1219–32, available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33776499/, accessed 15 May 2024.

Brady, S. S., J. M. Tschann, J. M. Ellen and E. Flores (2009), ‘Infidelity, trust, and condom use among Latino youth in dating relationships’, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 36 (4), 227–31, available at https://doi.org/10.1097/olq.0b013e3181901cba, accessed 28 May 2024.

Burton, L. (2007), ‘Childhood adultification in economically disadvantaged families: A conceptual model’, Family Relations, 56 (4), 329–45 available at https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00463.x, accessed 28 May 2024.

CDC (2008), ‘Sexually transmitted disease surveillance’, available at https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1570572700071899392, accessed 31 May 2024.

CDC (2021a), ‘STI treatment guidelines’, Online Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/default.htm, accessed 7 May 2024.

CDC (2021b), ‘Adolescents’, Online Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, available at https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/adolescents.htm, accessed 7 May 2024.

CDC (2021c), ‘Women who have sex with women (WSW) and women who have sex with women and men (WSWM)’, Online Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, available at https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/wsw.htm#:~:text=gonorrhoeae%20between%20women%20is%20unknown, accessed 7 June 2024.

CDC (2024a), ‘Sexually transmitted infections surveillance, 2022’, Online Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, available at https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/default.htm, accessed 7 May 2024.

CDC (2024b), ‘National overview of STIs, 2022’, Online Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, available at https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/overview.htm, accessed 7 May 2024.

Crooks, N., B. King and A. Tluczek (2019), ‘Protecting young black female sexuality’, Culture, Health & Sexuality, 22 (8), 1–16, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2019.1632488, accessed 29 May 2024.

Davidoff-Gore, A., N. Luke and S. Wawire (2011), ‘Dimensions of poverty and inconsistent condom use among youth in urban Kenya’, AIDS Care, 23 (10), 1282–90, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2011.555744, accessed 23 May 2024.

Duffin, E. (2022), ‘US population by gender 2027’, Online Statista, available at https://www.statista.com/statistics/737923/us-population-by-gender/#:~:text=Projection%20estimates%20calculated%20using%20the, accessed 4 June 2024.

Epstein, R., J. Blake and T. Gonzalez (2017), ‘Girlhood interrupted: The erasure of Black girls childhood’, Online SSRN Electronic Journal, available at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3000695, accessed 29 May 2024.

Ford, K. and J. M. Lepkowski (2004), ‘Characteristics of sexual partners and STD infection among American adolescents’, International Journal of STD & AIDS, 15 (4), 260–65, available at https://doi.org/10.1258/095646204773557802, accessed 22 May 2024.

Garcia, M. R. and A. A. Wray (2023), ‘Sexually transmitted infections’, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560808/, accessed 15 May 2024.

Gentry, M. (1998), ‘The sexual double standard’, Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22 (3), 505–11, available at https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1998.tb00173.x, accessed 28 May 2024.

Goldman, E. (1998), ‘Free love, American experience’, Online PBS, available at https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/goldman-free-love/, accessed 15 May 2024.

Gorgos, L. M. and J. M. Marrazzo (2011), ‘Sexually transmitted infections among women who have sex with women’, Online Clinical Infectious Diseases, 53 (3), S84–S91, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cir697, accessed 31 May 2024.

Hook, E. W. and R. D. Kirkcaldy (2018), ‘A brief history of evolving diagnostics and therapy for gonorrhea: Lessons learned’, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 67 (8), 1294–99, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy271, accessed 15 May 2024.

Hooper, R. R., G. H. Reynolds, O. G. Jones, A. A. Zaidi, P. J. Wiesner, K. P. Latimer, A. Lester, A. F. Campbell, W. O. Harrison, W. W. Karney, K. K. and Holmes (1978), ‘Cohort study of venereal disease. I: The risk of gonorrhea transmission from infected women to men’, American Journal of Epidemiology, 108 (2), 136–44, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112597, accessed 27 May 2024.

Hwang, L. Y., M. W. Ross, C. Zack, L. Bull, K. Rickman and M. Holleman (2000), ‘Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and associated risk factors among populations of drug abusers’, Online Clinical Infectious Diseases, 31 (4), 920–26, available at https://doi.org/10.1086/318131, accessed 28 May 2024.

James-Holmquest, A. N., J. Swanson, T. M. Buchanan, R. D. Wende and R. P. Williams (1974), ‘Differential attachment by piliated and nonpiliated neisseria gonorrhoeae to human sperm’, Online Infection and Immunity, 9 (5), 897–902, available at https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.9.5.897-902.1974, accessed 27 May 2024.

Jennings, L. K. and D. M. Krywko (2023), ‘Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)’, Online National Library of Medicine, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499959/, accessed 17 May 2024.

Johnson Lewis, J. (2019), “Free love and women’s history in the 19th century (and later).” ThoughtCo, available at www.thoughtco.com/free-love-and-womens-history-3530392, accessed 14 May 2024.

Kershaw, H. (2018), ‘Remembering the ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance’ campaign’, Online Placing the Public in Public Health: Public Health in Britain, 1948–2010, available at https://placingthepublic.lshtm.ac.uk/2018/05/20/remembering-the-dont-die-of-ignorance-campaign/, accessed 15 May 2024.

Ketterer, M. R., P. A. Rice, S. Gulati, S. Kiel, L. Byerly, J. D. Fortenberry, D. E. Soper and M. A. Apicella (2016), ‘Desialylation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Lipooligosaccharide by Cervicovaginal Microbiome Sialidases: The potential for enhancing infectivity in men’, Online Journal of Infectious Diseases, 214 (11), 1621–28, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiw329, accessed 27 May 2024.

Kirkcaldy, R. D., E. Weston, A. C. Segurado and G. Hughes (2019), ‘Epidemiology of gonorrhoea: A global perspective’, Sexual Health, 16 (5), 401, available at https://doi.org/10.1071/sh19061, accessed 15 May 2024.

Kleppa, E., S. D. Holmen, K. Lillebø, E. F. Kjetland, S. G. Gundersen, M. Taylor, P. Moodley and M. Onsrud (2014), ‘Cervical ectopy: Associations with sexually transmitted infections and HIV. A cross-sectional study of high school students in rural South Africa’, Sexually Transmitted Infections, 91 (2), 124–29, available at https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2014-051674, accessed 22 May 2024.

Knight, R., T. Falasinnu, J. L. Oliffe, M. Gilbert, W. Small, S. Goldenberg and J. Shoveller (2016), ‘Integrating gender and sex to unpack trends in sexually transmitted infection surveillance data in British Columbia, Canada: An ethno-epidemiological study’, BMJ Open, 6 (8), e011209, available at https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011209, accessed 22 May 2024.

The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, (2022), ‘Youth STIs: An epidemic fuelled by shame’, The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 6 (6), 353, https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-4642(22)00128-6, accessed 11 January 2025.

Lee, V., J. M. Tobin and E. Foley (2006), ‘Relationship of cervical ectopy to chlamydia infection in young women’, Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, 32 (2), 104–06, available at https://doi.org/10.1783/147118906776276440, accessed 22 May 2024.

Manhica, H., V. S. Straatmann, A. Lundin, E. Agardh and A. Danielsson (2020), ‘Association between poverty exposure during childhood and adolescence, and drug use disorders and drug‐related crimes later in life’, Online Addiction, 116 (7), available at https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15336, accessed 28 May 2024.

Maraynes, M. E., J. H. Chao, K. Agoritsas, R. Sinert and S. Zehtabchi (2017), ‘Screening for asymptomatic chlamydia and gonorrhea in adolescent males in an urban pediatric emergency department’, World Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, 6 (3), 154, available at https://doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v6.i3.154, accessed 22 May 2024.

Marks, M. J. and R. C. Fraley (2005), ‘The sexual double standard: fact or fiction? Sex roles’, 52 (3-4), 175–86, available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-1293-5, accessed 29 May 2024.

Medical Institute for Sexual Health (2024), ‘Racial/ethnic disparities and STIs’, available at https://www.medinstitute.org/racial-ethnic-disparities-and-stis/, accessed 28 May 2024.

Milhausen, R. R. and E. S. Herold (1999), ‘Does the sexual double standard still exist? Perceptions of university women’, Journal of Sex Research, 36 (4), 361–68, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499909552008, accessed 29 May 2024.

Nelson, T., J. Nandwani and D. Johnson (2021), ‘Gonorrhea and chlamydia cases are rising in the U.S. Sexually transmitted diseases’, available at https://doi.org/10.1097/olq.0000000000001479, accessed 8 May 2024.

NHS (National Health Service) (2017), ‘Chlamydia’, available at https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/chlamydia/#:~:text=sharing%20sex%20toys%20that%20are, accessed 8 May 2024.

NHS (2019), ‘Overview – gonorrhoea’, available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/gonorrhoea/, accessed 8 May 2024.

Okazaki, S. (2002), ‘Influences of culture on Asian Americans’ sexuality’, Journal of Sex Research, 39 (1), 34–41, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490209552117, accessed 24 May 2024.

Oliver, M. B. and C. Sedikides (1992), ‘Effects of sexual permissiveness on desirability of partner as a function of low and high commitment to relationship’, Social Psychology Quarterly, 55 (3), 321, available at https://doi.org/10.2307/2786800, accessed 29 May 2024.

Platt, R., P. A. Rice and W. M. McCormack (1983),’ Risk of acquiring gonorrhea and prevalence of abnormal adnexal findings among women recently exposed to gonorrhea’, Online JAMA, 250 (23), 3205–09, available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6417362, accessed 7 June 2024.

Public Health England (2021), ‘Promoting the sexual health and wellbeing of people from a Black Caribbean background: An evidence-based resource’, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/promoting-the-sexual-health-and-wellbeing-of-people-from-a-black-caribbeanbackground-an-evidence-based-resource, accessed 30 May 2024.

Quillin, S. J. and H. S. Seifert (2018), ‘Neisseria gonorrhoeae host adaptation and pathogenesis’, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 16 (4), 226–40, available at https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.169, accessed 9 May 2024.

Salazar, L. F., R. A. Crosby, R. J. DiClemente, G. M. Wingood, E. Rose, J. McDermott-Sales and A. M. Caliendo (2008), ‘African-American female adolescents who engage in oral, vaginal and anal sex: ‘Doing it all’ as a significant marker for risk of sexually transmitted infection’. AIDS and Behavior, 13 (1), 85–93, available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9381-5, accessed 24 May 2024.

Sentís, A., A. Prats-Uribe, E. López-Corbeto, M. Montoro-Fernandez, D. K. Nomah, P. G. de Olalla, L. Mercuriali, N. Borrell, V. Guadalupe-Fernández, J. Reyes-Urueña, J. Casabona and Catalan HIV and STI Surveillance Group (2021), ‘The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sexually transmitted infections surveillance data: Incidence drop or artefact?’, BMC Public Health, 21 (1), available at https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11630-x, accessed 3 June 2024.

Shannon, C. L. and J. D. Klausner (2019), ‘The growing epidemic of sexually transmitted infections in adolescents’, Online Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 30 (1), 137–43, available at https://doi.org/10.1097/mop.0000000000000578, accessed 7 May.

Shrider, E. (2023), ‘Poverty rate for the Black population fell below pre-pandemic levels’, available at https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/09/black-poverty-rate.html#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20Black%20individuals%20made, accessed 28 May 2024.

Sprecher, S., K. McKinney and T. L. Orbuch (1987), ‘Has the double standard disappeared?: An experimental test’, Social Psychology Quarterly, 50 (1), 24, available at https://doi.org/10.2307/2786887, accessed 29 May 2024.

Stamm, W. E., M. E. Guinan, C. C. Johnson, T. Starcher, K. K. Holmes and W. M. McCormack (1984), ‘Effect of treatment regimens for Neisseria gonorrhoeae on simultaneous infection with Chlamydia trachomatis’, The New England Journal of Medicine, 310 (9), 545–49, available at https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm198403013100901, accessed 10 May 2024.

Stenger, M. R., P. Pathela, G. Anschuetz, H. Bauer, J. Simon, R. Kohn, C. Schumacher and E. Torrone (2017), ‘Increases in the rate of Neisseria gonorrhoeae among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men—Findings from the sexually transmitted disease surveillance network 2010–2015’, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 44 (7), 393–97, available at https://doi.org/10.1097/olq.0000000000000623, accessed 31 May 2024.

Sutton, M. Y., N. F. Anachebe, R. Lee and H. Skanes (2021), ‘Racial and ethnic disparities in reproductive health services and outcomes 2020’, Online Obstetrics & Gynecology, 137 (2), 225–33, available at https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000004224, accessed 29 May 2024.

Tschann, J. M., N. E. Adler, S. G. Millstein, J. E. Gurvey and J. M. Ellen (2002), ‘Relative power between sexual partners and condom use among adolescents’, Journal of Adolescent Health, 31 (1), 17–25, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00418-9, accessed 22 May 2024.

Tzilos Wernette, G., K. Countryman, K. Khatibi, E. Riley and R. Stephenson (2020), ‘Love my body: Pilot study to understand reproductive health vulnerabilities in adolescent girls’, Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22 (3), 16336, available at https://doi.org/10.2196/16336, accessed 22 May 2024.

United States Census Bureau (2021), ‘U.S. Census Bureau quickfacts: United States’, Online United States Census Bureau, available at https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221, accessed 21 May 2024.

Van Gerwen, O. T., C. A. Muzny and J. M. Marrazzo (2022), ‘Sexually transmitted infections and female reproductive health’, Online Nature Microbiology, 7 (8), 1116–26, available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-022-01177-x, accessed 17 May 2024.

Wong, T., A. Singh, J. Mann, L. Hansen and S. McMahon (2004), ‘Gender differences in bacterial STIs in Canada’, Online BMC Women’s Health, 4 (S1), 26, available at https://doi.org/10.1186/14726874-4-S1-S26, accessed 17 May 2024.

Zenilman, J. M. (2001), ‘Ethnicity and STIs: More than black and white’, Sexually Transmitted Infections, 77 (1), 2–3, available at https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.77.1.2, accessed 28 May 2024.

Asymptomatic: Absence or perceived absence of symptoms.

Chlamydia: A sexually transmitted infection caused by Chlamydiae trachomatis, a bacterium that causes chlamydia.

Dysuria: Pain during urination.

Ectopic pregnancies: When a fertilised egg implants itself outside of the womb.

Epidemiology: The study of the causes, distribution and control of disease in a population.

Epididymitis: Inflammation (a natural response to infection, presenting as redness, swelling and pain) of the epididymis, located at the back of the testicle.

Gonorrhoea: A sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

HIV: A sexually transmitted infection caused by the Human Immunodeficiency Virus.

Monogamous: Referring to having one sexual partner at a time.

Oral sex: Using a mouth to stimulate another person’s genitals or anus.

Pandemic: An infectious disease prevalent over several countries or continents.

Proctocolitis: Inflammation of the rectum, the lower part of the large intestine, located near the anus.

Screening: STI screening can detect for the presence of a sexually transmitted infection.

Sexual encounter: A single instance of sexual activity, physical intimacy can vary.

Sexual network: A network of people that are linked through sexual relationships.

Sexual orientation: A personal pattern of romantic or sexual attraction.

Stigma:A negative social attitude toward a person or circumstance, can include shame.

Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI): A disease that can be transmitted through sexual contact.

Surveillance: Collecting information about the cases of STIs in a population.

Symptom: A feature (physical or mental) that indicates a disease.

Symptomatic: Presence of symptoms.

Transmission: The spread of something from one person to another.

Urethritis: Inflammation of the urethra.

To cite this paper please use the following details: Parnell, A. (2025), 'Age and Racial Disparities Persist for Gonorrhoea and Chlamydia in the United States', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 18, Issue 1, https://reinventionjournal.org/index.php/reinvention/article/view/1754. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities, please let us know by emailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.

https://doi.org/10.31273/reinvention.v18i1.1754, ISSN 1755-7429 © 2025, contact reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk. Published by the Institute for Advanced Teaching and Learning, University of Warwick. This is an open access article under the CC-BY licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)