Molly Fowler, University of Warwick; Leda Mirbahai, University of Warwick; Isabel Fischer, University of Warwick; Marie-Dolores Ako-Adounvo, Heart of Worcestershire College

Changes to admissions policies may have improved access to higher education, but equitable teaching and assessment strategies must address persisting attainment gaps. A diverse and inclusive assessment strategy is proposed to contribute towards reducing attainment deficits by providing learners with equality of opportunity. This study aims to elucidate student and staff experience of diverse assessments, to involve students in shaping the future of assessments, and to develop recommendations to overcome challenges associated with implementation. To achieve this, a mixed-methods survey (n = 54) explored students’ experiences of assessments. Focus groups (n = 7) led by students were conducted with some of the survey respondents. University educators (n = 6) participated in one-to-one semi-structured interviews. Student and staff data were analysed separately and assembled for comparison. Analysis revealed strong agreement between students and staff: both groups considered that diverse assessment would promote equitable opportunities in higher education. Participants recognised the need for a shift in culture to facilitate the implementation of a diverse assessment strategy that would promote equity of opportunity by improving accessibility and inclusivity. Moreover, implementation should be accommodated to the ‘learning journey’, welcoming students as equal co-creators and seeking to minimise the burden of assessments and marking.

Keywords: Inclusive assessment strategy, equity in assessment design, higher education, student co-creation, degree awarding gaps

Recruitment for diversity in the UK aims to enrich academic communities by increasing the demographic heterogeneity of the student population (HEA, 2022; Universities UK, 2023). Despite this progress, the existence of gaps in attainment suggests that persisting obstacles negatively impact the learning experience of formerly under-represented students once admitted to the university, including obstacles in assessment design (Arday et al., 2022). Policies promoting inclusivity in admissions have not necessarily been implemented in the core educational business of first-world universities, possibly leading to these attainment gaps (Cotton et al., 2015; Leslie, 2005; Richardson et al., 2020). Action is required to promote equity of opportunity after recruitment, including rethinking current assessment strategies.

According to anecdotal evidence cited by the British Medical Association (2020), medical students eligible for accommodations due to disability or neurodiversity frequently encounter difficulties in obtaining the reasonable adjustments they need.

The available adjustments, often stereotyped as variations in assessment environments and timings, have been criticised by some who argue they may provide an unfair advantage rather than truly levelling the playing field (Beck, 2022; Elliott and Marquart, 2004). Critics, including Healey et al. (2008), argue that the standard nature of these adjustments lacks theoretical justification, failing to consider the severity or form of neurodiversity such as dyslexia. Additionally, a recent systematic review by Clouder et al. (2020) criticises the ‘one size fits all’ approach, questioning whether these learning support plans effectively meet the individual needs of neurodivergent students. Some assessment types that are relatively impervious to adjustment, like presentations and clinical examinations, reduce equity of access for certain students.

For example, autistic students may struggle with the social components of presentations, including making and maintaining eye contact, and interpreting the emotions and intentions of others (Hand, 2023). Presentations typically rely on oral delivery, which may disadvantage neurodiverse students who experience challenges with speech fluency or managing distractions (Alderson et al., 2017; Takács et al., 2014).

A modern approach to academic inclusivity and accessibility in learning and assessment should recognise that the diversified needs of the current student population may have broader dimensions than previous cohorts.

Following the enforced changes to learning and assessments due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many universities have largely sought a return to ‘business as usual’ (Brooks and Perryman, 2023). However, the pandemic-driven accommodations, although imperfect, demonstrated that change is possible when necessary. Reports, such as the one from Quality and Qualifications Ireland (2020), revealed that marginalised groups faced more challenges with remote learning, highlighting the need for ongoing efforts to address inclusivity and accessibility in education.

There is no clear consensus on what constitutes diverse assessment. O’Neil and Padden (2022) identified two definitions: a wider variety of assessment types and a choice of assessment methodologies within each module. They also highlighted five obstacles to implementing diverse assessments, with ‘fear of students failing’ being the least concerning for staff and ‘fear of grade inflation’ being the most significant, underscoring the need for standardised marking. Contemporary learning and assessment must evolve with technology. Collins and Halverson (2009) argue that technology aims to improve the quality, efficiency and personalisation of learning to meet diverse learner demands. Lim et al. (2024) suggest that diverse assessment should include competencies such as the ethical use of artificial intelligence. Bearman et al. (2022) designed an e-assessment framework to integrate digital innovation into higher education. Academics broadly agree that diverse assessment uses a range of modalities targeting different types of learning, resulting in varied skill acquisition (Garside et al., 2009; O’Neil and Padden, 2022). This approach acknowledges diverse student strengths, learning styles and ways of demonstrating knowledge. A diverse assessment strategy also embraces a socio-political approach to addressing disadvantage (Nieminen, 2022), aligning with the social model of disability, which frames disability as a societal failure to achieve inclusivity. Charlton et al. (2022) highlighted the inconsistency in policy constructions of programme-level assessment strategies across Australia, emphasising the need for clear implementation guidelines.

Challenges in changing assessment policy include impacts on content delivery, resistance from students and staff, risks of widening the attainment gap, grade inflation, lack of resources and incongruent mark schemes (Armstrong, 2017; Bevitt, 2015; Kirkland and Sutch, 2009; Medland, 2016; O’Neil and Padden, 2022). Unsurprisingly, given these difficulties, the literature acknowledges that the increasing diversity of the student population is not adequately reflected in current assessment practices.

Thus, the aim of this study is to capture the experience and perceptions of students and staff regarding diverse assessment and to suggest practical recommendations for implementing such a strategy, involving students in shaping the future of assessments, and overcoming challenges to benefit the wider community.

This study asks how students and staff comprehend diverse and inclusive assessments, and how these groups perceive the challenges of a diverse assessment strategy. We seek to use the answers to these questions to inform the design of diverse assessments that promote effective learning.

A mixed-methods survey (n = 54) explored students’ experiences of ‘diverse assessment’ at a research-intensive university in the UK. Two focus groups led by students were conducted with some of the survey respondents (n = 7). University educators (n = 6) participated in one-to-one semi-structured interviews.

The semi-structured focus group interviews (n = 3 and n = 4 participants) were facilitated online by two student researchers, following the guidelines and steps recommended by Stalmeijer et al. (2014). At the time of data collection, both facilitators were undergraduate students with some experience of conducting interviews and focus groups. The senior authors, both experienced in mixed-method educational research, provided close oversight. Neither facilitator had a prior personal or professional relationship with the student participants, ensuring a separation that helped minimise bias and promote open dialogue during the interviews. Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the university where the research was conducted.

Participants and recruitment

Eligible participants included students who had successfully completed at least one year of study and staff involved in teaching or developing assessment strategies. Students with less than one year of study were excluded since most of the data collection took place in the Autumn term, before the majority of first-year students had experienced university-level assessment. Data collection comprised a questionnaire with 54 student responses and two semi-structured focus groups with seven student participants, while staff data was gathered through one-to-one interviews with six staff members. This methodology was deemed appropriate based on similar studies (Dicicco-Bloom and Crabtree, 2006; Dommett et al., 2019; Nolan and Roberts, 2021, 2022). Students were contacted through mailing lists and newsletters to distribute the participant information leaflet (PIL) and questionnaire. The PIL outlined the study’s rationale, participation details and withdrawal procedures, assurance that data from both the questionnaire and focus groups would be anonymised and that participation would not affect academic progression. Students interested in discussing their questionnaire responses were invited to the focus groups, with written consent obtained from all participants prior to participation. Staff members from various departments were invited to participate in one-hour semi-structured interviews via their institutional email, following a similar process regarding the PIL and consent forms.

Students

The online student questionnaire (n = 54) was hosted on the university’s SiteBuilder platform. The final question invited respondents to participate in focus groups. The semi-structured focus group interviews (n = 3 and n = 4 participants) were conducted according to guidelines and steps outlined by Stalmeijer et al. (2014) with participants joining online and facilitated by two researchers. Participants had their cameras on and could view and hear all participants and facilitators. Discussions were audio recorded. A semi-structured interview guide with a list of pre-agreed open-ended questions was used to guide the topic of conversation while also allowing participants to speak freely and introduce new considerations (Appendix 1).

Staff

Staff interviews (n = 6) were conducted online using Teams platform with discussions audio recorded. Each interview was conducted by one researcher, and a list of pre-agreed questions (Appendix 2) was used to guide participants’ discussion, while also enabling free-flowing dialogue.

Reflexive thematic analysis aims to inform understanding of participants’ perspectives and to structure and report themes (overarching patterns) within the dataset (Braun and Clarke, 2006). To elicit the themes, the transcripts were read by the researchers to enable familiarisation. Notable features in the data were then iteratively coded using an inductive approach over two rounds of coding for diligence and consistency (Braun and Clarke, 2012). Patterns and connections were actively sought in the codes, and similar codes were amalgamated inductively, identifying the final themes (Table A2 in Appendix 2). The generated codes, themes and the titles of themes were reviewed and discussed by the full research group to ensure the final themes accurately represented the data. Researchers maintained reflective notes throughout the analysis period, and these were discussed at researcher meetings. Discrepancies and disagreements between researchers were considered and discussed, enabling consensus to be reached. Once themes and codes were established, the final report was produced.

The thematic analysis of student and staff focus group and interview data resulted in the identification of seven common themes across student and staff data. The identified themes were:

The identified themes revealed an overlap in the experiences and views of current assessment approaches and future directions between students and staff, although the language and framing used by the two groups differed (Table 1).

Table 1: Results table showing the seven themes identified from the qualitative data.

Theme |

Sub-Theme |

Quotes |

Key Overall Finding |

||

Students |

Staff |

Students |

Staff |

||

Perceptions of diverse assessment |

|

|

|

|

|

Purpose of assessment |

|

|

|

|

|

Implementing change to assessment strategy |

|

|

|

|

|

Equity, fairness and inclusivity |

|

|

|

|

|

Culture shift and co-creation |

|

|

|

|

|

Best practice |

|

|

|

|

|

Challenges and key considerations |

|

|

|

|

|

Student data: Survey

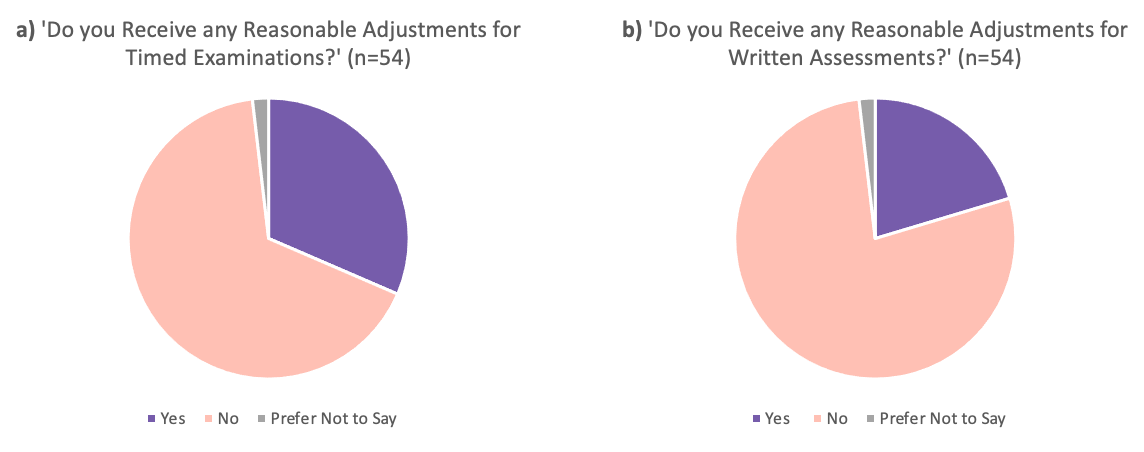

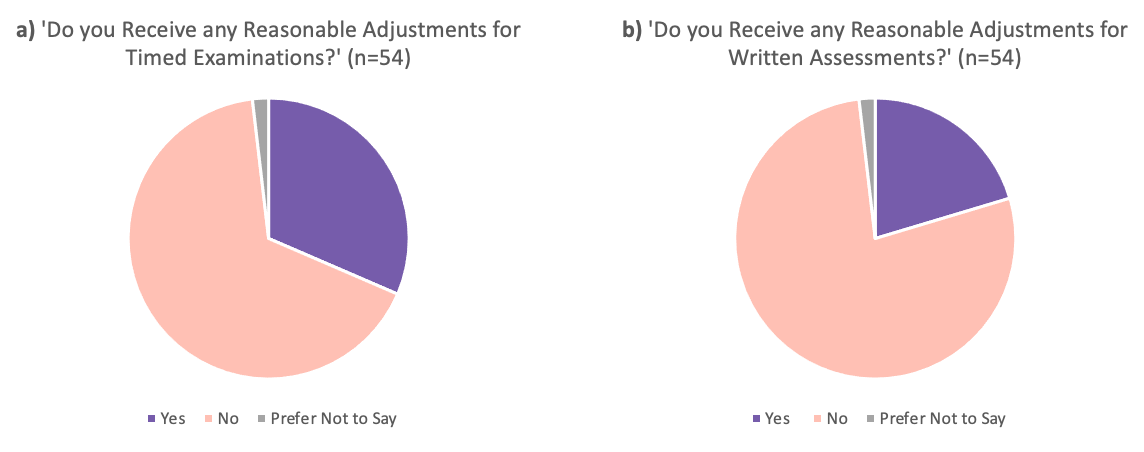

Student participants (n = 54) from 19 departments returned completed surveys. The Medical School had the highest representation (n = 16), followed by the Department of Economics (n = 9). Among the respondents, 17 required reasonable adjustments in timed exams, and 11 accessed adjustments in written assessments (Appendix 3). The assessment formats encountered by students are detailed in Appendix 4.

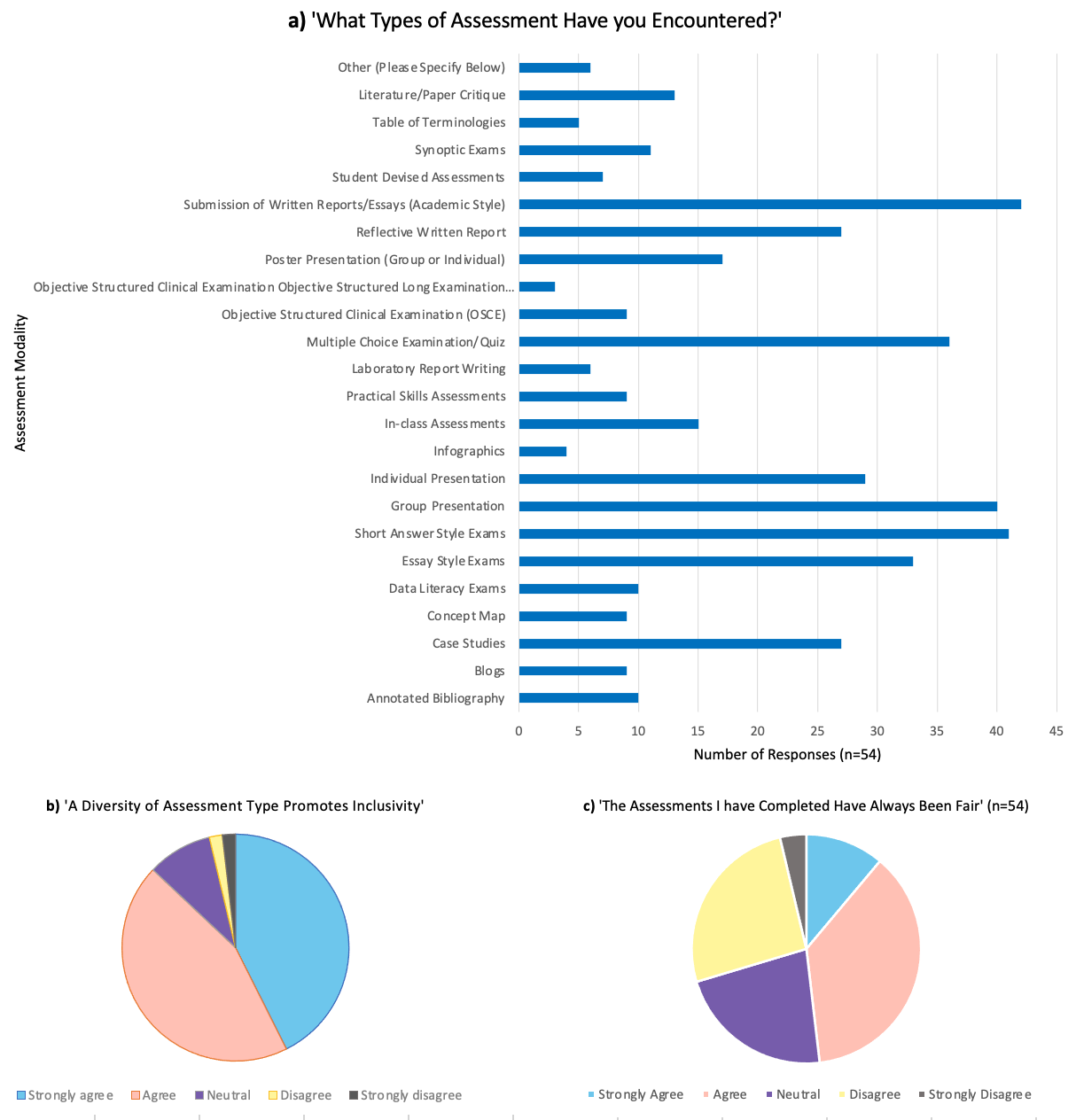

Of the 54 student participants, 46 answered the multiple-choice questions about circumstances affecting assessment completion or submission. 57 per cent of these cited ‘excessive workload’, 48 per cent mentioned ‘difficulty with time management’, 43 per cent found the ‘assessment challenging’ and 41 per cent had ‘external responsibilities such as family/caring commitments’ (Appendix 5).

In free-text responses, students favoured assessments that prioritise deep understanding and critical thinking over memorisation. They emphasised that effort should be the primary factor influencing grades. While various assessment methods were mentioned, no clear preference emerged. Fair assessments that account for individual differences and potential disadvantages, while avoiding bias, were reported as important to many students. Additionally, assessments accommodating disability and neurodiversity were seen as improving equitable opportunities for success.

The small focus groups, although potentially vulnerable to selection bias (Stone et al., 2023), provided richer data. Two focus groups (n = 3; n = 4) recruited students from the Medical School, Business School, Department of Economics, and Global Sustainable Development Faculty. Most of these participants favoured continuous assessment and coursework over end-of-year assessments and closed-book examinations. However, one student preferred having a dedicated time to focus on end-of-year assessment. When exploring the concept of diverse assessment, students characterised diverse assessment as a range of assessment modes that caters for the diversity of the student population.

‘[…] assessment types and options which work for everyone, including those with extra needs or from different backgrounds.’

Student focus group member

A key finding was the identification of language as a major contributor to determining assessment performance and fairness. Several participants, who were international students (n = 4) and spoke English as a second language, reported that certain assessments unfairly advantaged native English speakers. Specifically, multiple-choice exams may employ intricate language that is more challenging to interpret for individuals with English as a second language.

‘[…] in multiple-choice exams, specifically where I just felt like… why am I thinking about grammar in an exam which is about human biology?’

Student focus group member

Another participant argued that group work can be more challenging from a language and cultural perspective.

‘[…] I was working with a group and they were all very silent. And suddenly I noticed that they had switched on the transcript in Microsoft Word…you don’t know whether they are not contributing to the conversation or the discussion because they’re uncomfortable with the language or because in some cultures it’s simply not okay to disagree with somebody.’

Student focus group member

A consensus emerged that using diverse assessment has the potential to both provoke deeper learning and to ensure all students have equitable opportunity to demonstrate their learning based on their strengths and preferred assessment mode. Furthermore, the students agreed that a diverse assessment strategy should incorporate choice and flexibility to reduce the assessment burden.

‘[…] it should be five different assessments of which the student can choose one or two.’

Student focus group member

However, students did express concerns that diverse assessments may increase the number of assessments. While all students felt that assessments should stimulate learning, they considered that the current design prioritised recall of factual knowledge over promoting and valuing depth of understanding. Students envisaged future assessments that should focus on considering the student ‘learning journey’ and the development of skills and knowledge that have long-term and future application beyond their studies. Finally, although students were enthusiastic about the concept of co-creation in assessment design, they expressed concerns regarding upholding academic integrity and that students lack knowledge of university assessment policy.

‘The only thing that really counts is kind of the number that’s put on at the end of it, and that annoys me because I would like assessments to be a part of my learning journey […]’

Student focus group member

‘What we can actually do is make them [assessments] more appropriate for the future of that person and actually use assessment as a training opportunity as opposed to examination at the end of a course or periodic assessment; we can actually use it as a teaching tool as well. And I think we should be diversifying assessment beyond simply assessment, but also looking at an application of learning as opposed to an assessment of knowledge, while still retaining the assessment of knowledge.’

Student focus group member

Staff members (n = 6) from different departments participated in semi-structured interviews. There was significant overlap (Table 1) between the views expressed by the staff and students regarding current assessment approaches and future directions, although the language and framing used by the two groups differed.

When exploring the definition of ‘diverse assessment’, interviewees emphasised that equitable opportunities should be provided in assessment, but several also highlighted that the concept of ‘diverse assessment’ should also be incorporated into teaching methods, provision of materials and overall course structure to promote equity and inclusivity. Offering students variability, choice and flexibility was perceived to enhance learning of transferrable skills and maintain motivation. However, the key function of assessments should be to promote learning as part of a broader ‘learning journey’. Traditional closed-book exams were perceived by some as outdated as learning for them is often strategic and short-lived.

‘[…] it means that there is not one particular cohort of students that is disadvantaged by the choice of diversity that you use for your assessment strategy.’

Staff interviewee

‘Simple old old-school exams. Memorise this. Regurgitate it, because two hours after the exam, no one remembers anything they wrote in the paper. That’s not promoting student learning. In my mind, I do a lot of work with rethinking assessment, and in my mind, I’d love to scrap exams.’

Staff interviewee

Some staff expressed concerns that use of diverse assessments can potentially lead to over-assessments of students and increase workload burden for staff. Pedagogically, revisiting and building on previous learning is highly effective and this also presents an opportunity to prevent over-assessment, retain an acceptable level of marking burden and improve feedback for students while employing a diverse portfolio of assessment modes.

‘I get three weeks to mark, maybe 600 essays. Yep, I can’t be spending more than 10 minutes per essay, and that includes feedback. Because otherwise I won’t mark them in time. […] If you remove that burden, though, 600 essays and you space them out throughout the year, I’m now spending 20 minutes per essay. Which means that the standard of marking will improve […]’

Staff interviewee

Transparency of assessments and of marking criteria was considered ‘best practice’ to promote student confidence and to facilitate learning. Likewise, accessibility, reasonable adjustments and mitigation were important considerations for assessment design. In practice, assessments favour neurotypical, able-bodied, native English-speaking, technology-literate individuals with no caring responsibilities.

‘[…] a transparency with the students, with how that’s going to be assessed and then a development of the skills to allow them then to utilise that particular mode of assessment that you’ve chosen within the diverse assessments that you might have […]’

Staff interviewee

University politics and hierarchies were perceived to hinder change. Several interviewees discussed the challenge of ‘inheriting’ modules and assessments and facing difficulties in altering or updating content without impacting other linked modules. This further highlighted the need for course-level review of assessment strategies.

Staff expressed openness to involving students as co-creators in assessment design. However, there was a concern that for the co-creation to work effectively, this process should include a diverse group of students from a wide range of backgrounds and attainment levels. Although there was enthusiasm for the implementation of a diverse assessment strategy, staff recognised this would be difficult without a culture change.

The views of students and staff were aligned, with both groups expressing the same concerns and hopes for the future of assessments. While students focused on the impact of change, staff framed their ideas around models of pedagogy and the practicalities of implementing change in assessment.

Students and staff characterised diverse assessment as a range of methodologies examining different pedagogic domains and skills, aligning with DeLuca and Lam’s (2014) findings on assessment practices supporting learners. Diverse assessment should enhance equity by accounting for complex student needs, using reasonable adjustments and compassionate mitigation policies. Implementation should focus on flexibility and choice without increasing assessment numbers or marking burden (Tai et al., 2022). Students grouped diverse and inclusive assessments together, while staff differentiated between diversity and inclusivity. Both groups raised concerns about the transition period to a new assessment approach. Student co-creation in assessment design has been proposed (Bovill, 2012; Neary, 2010) but presents challenges in the UK’s marketised higher education system. Respondents emphasised that assessments should contribute to a broader ‘learning journey’, aligning with Bloxham’s (2007) argument on assessment-driven behaviours. Fischer et al. (2023) demonstrated that summative assessments initiate learning but may not significantly influence learning practices. Students advocated for assessment choice within modules, while staff favoured improved reasonable adjustments. This tension reflects ongoing discourse in educational literature (Lawrie et al., 2017; Waterfield and West, 2008) on balancing inclusive assessment design with practical implementation.

Students and some staff advocated for offering a choice of assessment types, aligning with research suggesting that this can increase student engagement and motivation (Kessels et al., 2024). However, standardising marking and ensuring equal attainment of learning outcomes is challenging with multiple assessment options.

Reasonable adjustments, mitigation and flexibility should level the playing field to enable all students to demonstrate the same learning outcomes. However, current adjustments are often seen as inadequate and difficult to access (Bain, 2023).

Offering pedagogically valid assessment choices that facilitate course-level learning outcomes is supported by Neil and Padden (2022), who argue that student preferences depend on background, subject area, personal reasons and previous experiences. This suggests that students may perform better with a range of assessment modalities. Greater flexibility with deadlines and humane mitigation policies are especially important for students with health, social and financial pressures. Research indicates that many students work out of financial necessity, which can create an inequitable environment favouring more privileged students (Dennis et al., 2018).

Disabled, neurodiverse and international students are often most disadvantaged by traditional assessments. Viewing assessments as part of a ‘learning journey’ that includes accessible teaching materials and reasonable adjustments may be the best equaliser. This aligns with the concept of ‘assessment for inclusion’ (Tai et al., 2022), which advocates assessments that do not disadvantage diverse students. Strategies like authentic assessment and programmatic assessment can improve fairness and inclusivity (Dawson, 2020; Gulikers et al., 2004; Tai et al., 2022).

Both students and staff wanted assessments to have real-world applications, moving away from memorisation-based models. They favoured assessments that test critical thinking and interpretation. While traditional closed-book exams and multiple-choice questions were seen as discriminatory, some research suggests closed-book tests can stimulate deep learning (Heijne et al., 2008).

Optionality in assessments may be idealised but impractical to implement and standardise. Reasonable adjustments should be more accessible and tailored to individual needs. Current processes for obtaining adjustments are often lengthy and undignified, as highlighted by Kendall (2018). There is a strong argument for overhauling the system of reasonable adjustments and mitigations to provide equitable opportunities for all students. If assessments aim to teach skills and embrace diversity, this should be reflected in their design to ensure fairness (Aristotle, 1999).

Students and staff acknowledged the challenges in implementing a diverse and inclusive assessment strategy, noting a tension between their perspectives and the academic ecosystem. Staff often feel constrained by practical limitations such as timetabling, room availability and cohort size, which affect assessment arrangements. Traditional reasonable adjustments have primarily focused on in-person examinations, leading to confusion about the most suitable adjustments for diverse assessments. This inconsistency raises the question of whether reasonable adjustments should be standardised or personalised. To improve this situation, departments require better guidance and support in designing assessments that facilitate equal opportunities. Literature suggests that while standardising some adjustments can help address common barriers, individual circumstances often necessitate personalised solutions. For example, Cardiff University advocates for a combination of standardised and individualised adjustments, such as providing electronic copies of lecture materials and extended library loans, to ensure effectiveness while maintaining academic standards (Cardiff University, 2025). This confirms the importance of a balanced approach to effectively support disadvantaged students in higher education.

University policies and bureaucratic procedures can hinder or delay the implementation of diverse assessment strategies. Staff expressed concerns about the invisible politics and hierarchies within the university that obstruct revisions to teaching and assessments. Many described feeling constrained by ‘inherited modules’ from previous professors, which limits their ability to innovate. Empowering staff, particularly module leads, to take control of their teaching and assessments is essential for fostering positive change.

Despite enthusiasm for a diverse assessment strategy, staff remain cautious about its implementation. Changing university culture and policy is challenging, and both students and staff may resist such changes. Research indicates that resistance to change in higher education often stems from faculty culture, resource allocation and leadership dynamics (Chandler, 2013). Successful change management requires strong role models and effective leadership, suggesting that meaningful progress is possible even within complex institutional cultures.

To facilitate the implementation of diverse assessment strategies, it is crucial to provide educators with clear definitions, examples and support for experimentation. Addressing concerns about grade inflation and ensuring alignment between assessment methods and learning outcomes will reassure educators that diverse assessments can maintain academic standards while promoting student success. Ultimately, empowering staff to manage their teaching and assessments can yield significant benefits, but it necessitates careful consideration of potential barriers and proactive measures to support both educators and students throughout the transition.

Both students and staff recognised the benefits of student co-creation in designing and trialling new assessments, although they acknowledged the associated challenges, including the importance of academic integrity and students’ limited understanding of existing assessment policies. Staff shared similar concerns while emphasising the difficulty in recruiting students from diverse backgrounds, as their absence could perpetuate inequities.

Students identified a conflict of interest when involved in assessment design, fearing that staff might not be receptive to their ideas. Conversely, staff expressed a strong desire to better understand the student perspective, advocating for co-creation as a true partnership rather than a mere consultation process (Bevitt, 2015). Both groups acknowledged that students often lack knowledge of university rules and regulations. High-quality feedback was deemed essential by both students and staff, yet neither group was fully satisfied with the current feedback model. There is a shared desire for a culture shift that fosters co-creation and provides high-quality feedback to support learning while maintaining a work-life balance.

Students and staff advocated for transparent assessments that emphasise knowledge application and critical thinking rather than rote memorisation. They asserted that for an assessment to be considered best practice, it must provide equitable opportunities for all students, taking into account diversity factors such as disability, neurodiversity, income, caring responsibilities and language barriers. Both groups – staff and students – expressed the need for elements of choice and flexibility, improved reasonable adjustments and mitigation strategies, while emphasising that a diverse assessment strategy should not lead to an increased assessment burden.

The discussion highlighted complexities in the implementation of choice within modules, stressing that diversification should occur at the course level and throughout the curriculum to avoid over-assessment. This perspective aligns with O’Neill and Padden’s (2022) argument that educators need to understand students’ assessment experiences across their programmes, suggesting a comprehensive approach that transcends individual modules. The recommendation to share examples within teaching and learning circles further supports a curriculum-wide strategy.

Using formative and summative assessments, along with clear marking criteria and detailed feedback, was seen as vital for building student confidence and motivation in preparation for the workforce. Tai et al. (2022) corroborate these findings, noting that students have varying assessment goals based on their individual circumstances. The proposed ideal diverse and inclusive assessment strategy is based on a spiral curriculum with constructive alignment, where learning outcomes are defined before teaching and assessments are designed (Mazouz and Crane, 2013). This approach involves establishing engaging course-level learning outcomes that are broken down into modules, allowing students to revisit knowledge and build skills. This method fosters deeper learning and enhances student confidence (Johnson, 2017). Each assessment should have a clear purpose in the learning journey and should focus on a manageable number of objectives.

Exploring assessment diversification at the course level rather than at the module level allows for the reuse of assessment modes, enabling students to practise new skills and build confidence without the risk of over-assessment or increased marking burdens.

The main challenges identified by staff and students were workload and equity in implementing a diverse assessment strategy. Concerns were raised about increased assessment burden for students and marking burden for staff, potentially turning assessments into a strategic exercise rather than an enriching experience.

To mitigate workload, a continuous assessment model with sensitive reasonable adjustments and course-level diversification is recommended. Careful consideration of choice implementation is necessary to ensure standardised marking and equal opportunities. Prioritising the learning journey helps ensure assessments have purpose.

The literature highlights student engagement and empowerment as key benefits of diverse assessment methods. While time and resources are perceived as barriers, studies suggest these may be more perceived than actual (Bevitt, 2015). Providing educators with examples and support can help overcome these barriers. Participants emphasised the importance of equitable assessments that improve accessibility and inclusivity.

As universities adapt to integrating AI into assessment strategies with a focus on critical thinking and practical application of knowledge, co-creation with students is particularly opportune as the impact of such potentially profound change must be confronted by both staff and students. Chan’s AI Ecological Education Policy Framework (2023) addresses the implications of AI integration in academic settings. Key considerations for incorporating AI into assessment strategies include redesigning assessments, developing AI literacy programmes, creating opportunities for AI application, emphasising ethical considerations and collaborating with industry partners.

Involving students as co-investigators emphasises the community of interest between students and academics in university life. We have therefore modelled the collaboration advocated in the recommendations for future action. Despite the small number of participants and our location in a single UK university, the methodology has harvested a significant body of rich data that can inform future research and practice.

The primary finding of this study is the synergy between students and staff. Diverse assessment is perceived as a way of improving inclusivity, accessibility and equity. Staff were more likely to appreciate the distinction between diverse and inclusive assessments, and the impact this would have on implementing the ideal assessment strategy. The consequent debate about whether to include choice within module or course level or to focus on improving reasonable adjustments is complex. Based on the data, the study justifies a carefully thought-out approach that considers improving both aspects in course-level assessment design.

This study corroborates the vulnerability of students with disability, neurodiversity, language obstacles, caring responsibilities and financial hardship that could be ameliorated with the introduction of diversity in assessment. Students and staff feel that each assessment should have a purpose and contribute to the ‘learning journey’ without producing an unnecessary burden. A culture shift is necessary to implement more accessible teaching, improved reasonable adjustments, mitigation procedures and student co-creation. Obstructive hierarchies should be dissolved so staff can update their modules and assessments to better reflect the current context and to support students more effectively.

As a result of the study, the authors make the following recommendations:

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Table 1: Results table showing the seven themes identified from the qualitative data.

Table A1: Pre-agreed questions and prompts for the student focus groups.

Table A2: Pre-agreed questions and prompts for the staff interviews.

A list of pre-agreed open-ended questions was used to guide the topic of conversation for student focus group interviews.

Table A1: Pre-agreed questions and prompts for the student focus groups.

Topic |

Prompts |

Introduction |

|

General feelings towards assessment |

|

Understanding diverse assessment |

|

Fairness |

|

Current assessment approaches/ methods |

|

Inclusivity |

|

Benefits and challenges of diverse assessment |

|

Ideal learning experience |

|

Implementation |

|

A list of pre-agreed open-ended questions was used to guide the topic of conversation for staff interviews.

Table A2: Pre-agreed questions and prompts for the staff interviews.

Topic |

Prompt |

Understanding of diverse assessment |

|

Assessment approaches |

|

Student impact |

|

Resources |

|

Assessment design |

|

Pie charts showing the proportion of students in the survey population who receive reasonable adjustments for: (a) timed examinations, (b) written assessments.

Graphs showing data collected from the student survey: (a) types of assessments students have encountered, (b) agreement with the statement ‘A diversity of assessment type promotes inclusivity’, (c) agreement with the statement ‘The assessments I have completed have always been fair’.

Graph showing students’ responses to a multiple-choice survey question regarding circumstances affecting assessments.

Alderson, R. M., C. H. G. Patros, S. J. Tarle, K. L. Hudec, L. J. Kasper and S. E. Lea (2017), ‘Working memory and behavioral inhibition in boys with ADHD: An experimental examination of competing models’, Child Neuropsychology, 23 (3), 255–72

Arday, J., C. Branchu and V. Boliver (2022), ‘What do we know about Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) participation in UK higher education?’, Social Policy and Society, 21 (1), 12–25, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s1474746421000579, accessed 24 August 2024

Aristotle, R. W. D. (TR). (1999), ‘Chapter V’, in Nicomachean Ethics, Kitchener, Ontario: Batoche Books, pp. 71–90.

Armstrong, L. (2017), ‘Obstacles to innovation and change in higher education’, available at https://www.tiaa.org/content/dam/tiaa/institute/pdf/full-report/2017-03/armstrong-barriers-to-innovation-and-change-in-higher-education.pdf, accessed 31 August 2024

Bain, K. (2023), ‘Inclusive assessment in higher education: What does the literature tells us on how to define and design inclusive assessments?’, Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, (27), available at https://journal.aldinhe.ac.uk/index.php/jldhe/article/view/1014, accessed 31 August 2024

Bearman, M., J. H. Nieminen and J. Ajjawi (2022), ‘Designing assessment in a digital world: An organising framework’, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 48 (3), 291–304, available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02602938.2022.2069674, accessed 31 August 2024

Beck, S. (2022), ‘Evaluating the use of reasonable adjustment plans for students with a specific learning difficulty’, British Journal of Special Education, 49 (3), 399–419, available at https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12412, accessed 31 August 2024

Bevitt, S. (2015), ‘Assessment innovation and student experience: A new assessment challenge and call for a multi-perspective approach to assessment research’, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40 (1), 103–19, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.890170, accessed 31 August 2024

Bloxham, S. (2007), ‘A system that is wide of the mark’, available at http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=310924, accessed 31 August 2024

Bovill, C. (2012) ‘Students and staff co-creating curricula: A new trend or an old idea we never got around to implementing?’ available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279448385_Students_and_staff_co-creating_curricula_a_new_trend_or_an_old_idea_we_never_got_around_to_implementing, accessed 31 August 2024

Braun, V. and V. Clarke (2006), ‘Using thematic analysis in psychology’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2), 77–101, available at https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa, accessed 26 May 2025

Braun, V, and V. Clarke (2012), ‘Thematic Analysis’, in H. Cooper et al. (ed). Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. Vol 2., pp. 57–71, American Psychological Association, available at https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/13620-000, accessed 26 May 2025

British Medical Association (2020), ‘Disability in the medical profession: Survey findings 2020’, available from https://www.bma.org.uk/media/2923/bma-disability-in-the-medical-profession.pdf, accessed 31 August 2024

Brooks, C. and J. Perryman (2023), ‘Policy in the pandemic: Lost opportunities, returning to ‘normal’ and ratcheting up control’. London Review of Education, 21 (1), 23, available from: https://doi.org/10.14324/LRE.21.1.23, accessed 24 May 2025

Cardiff University (2025), Reasonable adjustments policy and procedure, available at: www.cardiff.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/1560477/Reasonable-Adjustment-Procedure.pdf, accessed 20 August 2025

Chan, C. K. Y. (2023), ‘A comprehensive AI policy education framework for university teaching and learning’, International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20 (1), 38.

Chandler, N. (2013), ‘Braced for turbulence: Understanding and managing resistance to change in the higher education sector’, Management, 3 (5): 243-51, available at http://article.sapub.org/10.5923.j.mm.20130305.01.html, accessed 20 August 2025

Charlton, N., L. Weir and R. Newsham-West (2022), ‘Assessment planning at the program-level: A higher education policy review in Australia’, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47 (8), 1475–88, available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02602938.2022.2061911, accessed 31 August 2024

Clouder, L., M. A. Karakus, M. V. Cinotti, G. A. Ferreyra and P. Rojo (2020), ‘Neurodiversity in higher education: A narrative synthesis’, Higher Education, 80 (4), 757–78, available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00513-6, accessed 31 August 2024

Collins, A. and R. Halverson (2009), ‘Rethinking education in the age of technology: The digital revolution and the schools’, available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264869053_Rethinking_education_in_the_age_of_technology_the_digital_revolution_and_the_schools, accessed 31 August 2024

Cotton, D. R. E., M. Joyner, R. George and P. A. Cotton (2015), ‘Understanding the gender and ethnicity attainment gap in UK higher education’, Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 53 (5), 475–86, available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14703297.2015.1013145, accessed 31 August 2024

Dawson, P. (2020), Defending assessment security in a digital world: Preventing e-cheating and supporting academic integrity in higher education, London: Routledge

Dennis, C., J. Lemon and V. Louca (2018), ‘Term-time employment and student attainment in higher education’, Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice, 6 (1), available at https://doi.org/10.14297/jpaap.v6i1.294, accessed 31 August 2024

DeLuca, C. and C. Y. Lam (2014), ‘Preparing teachers for assessment within diverse classrooms: An analysis of teacher candidates’ conceptualizations’, Teacher Education Quarterly, 41 (3), 3–24

Dicicco-Bloom B. and B. F. Crabtree (2006), ‘The qualitative research interview’, Med Edu., 40 (4), 314–21, available at https://asmepublications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x, accessed 31 August 2024

Dommett, E. J., B. Gardner and W. van Tilburg (2019), ‘Staff and student views of lecture capture: A qualitative study’, Int J Educ Technol High Educ, 16 (23), available at https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0153-2, accessed 31 August 2024

Elliott, S. N., and A. M. Marquart (2004), ‘Extended time as a testing accommodation: Its effects and perceived consequences’, Exceptional Children, 70 (3), 349–67, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290407000306, accessed 31 August 2024

Fischer, J., M. Bearman, D. Boud and J. Tai (2023), ‘How does assessment drive learning? A focus on students’ development of evaluative judgement’, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02602938.2023.2206986, accessed 31 August 2024

Garside, J., J. Z. Nhemachena, J. Williams and A. Topping (2009), ‘Repositioning assessment: Giving students the ‘choice’ of assessment methods’, Nurse Education in Practice, 9 (2), 141–48, available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19006681/, accessed 31 August 2024

Gulikers, J. T. M., T. J. Bastiaens and P. A. Kirschner (2004), ‘A five-dimensional framework for authentic assessment’, Educational Technology Research and Development, 52 (3), 67–86

Hand, C. J. (2023), ‘Neurodiverse undergraduate psychology students’ experiences of presentations in education and employment’, Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 15 (5),1600–17

Healey, M., H. Roberts, M. Fuller, J. M. Georgeson, A. Hurst, K. Kelly, S. Riddell and E. Weedon (2008), Reasonable adjustments and disabled students’ experiences of learning, teaching and assessment’, available at https://researchportal.plymouth.ac.uk/en/publications/reasonable-adjustments-and-disabled-students-experiences-of-learn, accessed 01 September 2024

Heijne, M., J. Kuks, W. Hofman and J. Cohen-Schotanus (2008), ‘Influence of open- and closed-book tests on medical students’ learning approaches’, Medical Education, 42, 967–74

Johnson, H. (2017). ‘The spiral curriculum: Research into practice’, available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED538282.pdf, accessed 01 September 2024

Kendall, L. (2018), ‘Supporting students with disabilities within a UK university: Lecturer perspectives’, Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 55 (6), 694–703

Kessels, G., K. Xu, K. Dirkx and R. Martens (2024), ‘Flexible assessments as a tool to improve student motivation: An explorative study on student motivation for flexible assessments’, Frontiers in Education, 9, available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379697959_Flexible_assessments_as_a_tool_to_improve_student_motivation_an_explorative_study_on_student_motivation_for_flexible_assessments, accessed 01 September 2024

Kirkland, K. and D. Sutch (2009), ‘Overcoming the obstacles to educational innovation: A literature review’, Futurelab, available at https://www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/FUTL61/FUTL61.pdf, accessed 01 September 2024

Lawrie, G., E. Marquis, E. Fuller, T. Newman, M. Qiu, M. Nomikoudis, F. Roelofs and L. Van Dam (2017), ‘Moving towards inclusive learning and teaching: A synthesis of recent literature’, Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 5 (1), available at https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/tli/article/view/57469, accessed 01 September 2024

Leslie, D. (2005), ‘Why people from the UK’s minority ethnic communities achieve weaker degree results than whites’, Applied Economics, 37, 619–32

Lim, T., S. Gottipati and M. Cheong (2024), ‘Educational technologies and assessment practices: Evolution and emerging research gaps’, in Reshaping Learning with Next Generation Educational Technologies Publisher: IGI Global, available from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/378214251_Educational_Technologies_and_Assessment_Practices_Evolution_and_Emerging_Research_Gaps, accessed 01 September 2024

Mazouz, A. and K. Crane (2013), ‘Application of matrix outcome mapping to constructively align program outcomes and course outcomes in higher education’, Journal of Education and Learning, 2 (4), 166–76, available at https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1077162, accessed 01 September 2024

Medland, E. (2016), ‘Assessment in higher education: Drivers, obstacles and directions for change in the UK’, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41 (1), 81–96, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.982072, accessed 01 September 2024

Neary, M. (2010), ‘Student as producer’, available at https://josswinn.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/15-72-1-pb-1.pdf, accessed 01 September 2024

Nieminen, J. H. (2022), ‘Unveiling ableism and disablism in assessment: a critical analysis of disabled students’ experiences of assessment and assessment accommodation’, Higher Education, 85, 613–36, available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10734-022-00857-1, accessed 01 September 2024

Nolan, H. A. and L. Roberts (2021), ‘Medical educators’ views and experiences of trigger warnings in teaching sensitive content’, Med Educ, 55 (11), 1273–83, available at https://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/id/eprint/153559/, accessed 01 September 2024

Nolan, H. A, and L. Roberts (2022), ‘Medical students’ views on the value of trigger warnings in education: A qualitative study’, Med Educ, 56 (8), 834–846, available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35352384/, accessed 01 September 2024

Quality and Qualifications Ireland (2020), ‘The impact of COVID-19 modifications to teaching, learning and assessment in Irish further education and training and higher education’, available at https://www.qqi.ie/sites/default/files/2022-04/the-impact-of-covid-19-modifications-to-teaching-learning-and-assessment-in-irish-further-education-and-training-and-higher-education.pdf, accessed 01 September 2024

O’Neill, G. and L. Padden (2022), ‘Diversifying assessment methods: Obstacles, benefits and enablers’, Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 59 (4), 398–409, available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349030041_Diversifying_assessment_methods_Barriers_benefits_and_enablers, accessed 01 September 2024

Richardson, J. T. E., J. Mittelmeier and B. Rienties (2020), ‘The role of gender, social class and ethnicity in participation and academic attainment in UK higher education: An update’, Oxford Review of Education, 46 (3), 346–62, available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03054985.2019.1702012, accessed 01 September 2024

Stalmeijer, R. E., N. McNaughton and W. N. K. A. Van Mook (2014), ‘Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 91’, Medical Teacher, 36 (11), 923–39, available at https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.917165, accessed 26 May 2025

Stone, A. A., S. Schneider, J. M. Smyth, D. U. Junghaenel, M. P. Couper, C. Wen, M. Mendez, S. Velasco and S. Goldstein (2023), ‘A population-based investigation of participation rate and self-selection bias in momentary data capture and survey studies’, Curr Psychol, available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04426-2, accessed 01 September 2024

Takács, Á., A. Kóbor, Z. Tárnok, and V. Csépe (2014), ‘Verbal fluency in children with ADHD: Strategy using and temporal properties’, Child Neuropsychology, 20 (4), 415–29

Tai, J. H., M. Dollinger, R. Ajjawi, T. Jorre de St Jorre, S. Krattli, D. McCarthy and D. Prezioso (2022), ‘Designing assessment for inclusion: An exploration of diverse students’ assessment experiences’, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 48 (3), 403–17, available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02602938.2022.2082373, accessed 01 September 2024

Universities UK (2023), ‘Higher education in facts and figures: 2021’, available at https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/what-we-do/policy-and-research/publications/higher-education-facts-and-figures-2021, accessed 01 September 2024

Waterfield, J. and B. West (2008), ‘Towards inclusive assessments in higher education’, available from: https://eprints.glos.ac.uk/3858/2/Lathe_3_Waterfield_West.pdf, accessed 01 September 2024

Assessment strategy: An assessment strategy is the co-ordinated, whole‑course plan of assessment practices designed to align with clear learning outcomes, criteria and teaching activities. It guides when and how students are evaluated, supports meaningful feedback and development, and fosters deep learning rather than surface memorisation.

Spiral curriculum: An approach where key concepts are revisited multiple times, each encounter building on prior knowledge with increasing complexity and depth. Its aim is to foster long-term proficiency by progressively deepening understanding rather than covering topics just once.

https://doi.org/10.31273/reinvention.v18i2.1749, ISSN 1755-7429, c 2025, contact, reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk. Published by Institute for Advanced Teaching and Learning, University of Warwick. This is an open access article under the CC-BY licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

To cite this paper please use the following details: Fowler, M., Mirbahai, L., Fischer, I., Ako-Adounvo, M.-D. (2025), 'Insights into Diversity: A Multi-Stakeholder Analysis of Inclusive Assessment Practices in Higher Education', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 18, Issue 2, https://reinventionjournal.org. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities, please let us know by emailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.

© 2025, contact reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk. Published by the Institute for Advanced Teaching and Learning, University of Warwick. This is an open access article under the CC-BY licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)