Albert Oliver i Ribé, University of Warwick

This paper investigates the moral distinctions between private brands (or private labels) and national brands within the context of economic, sustainability and innovation impacts. Private brands, owned and controlled by retailers, increasingly dominate the market, raising ethical concerns. Key areas of analysis include economic effects on consumers and producers, sustainability practices and the ethical implications of innovation and image copying. The findings suggest that private brands are morally inferior to national brands due to their detrimental impact on sustainability and innovation. The paper concludes with proposed political interventions aimed at mitigating these ethical issues, highlighting the need for more stringent regulations to ensure fair practices and enhance sustainability within the industry.

Keywords: Private Brands, National Brands, Ethical concerns about private brands, Retail sustainability, Brand innovation, economic impact of branding

Private brands and national brands compete in a market full of ethical issues such as economic balances between producers and consumers, the equilibria between sustainability and price competitiveness, or the morality of copying other companies’ innovation. In this confrontation between national brands and retailers, the latter have an increasing advantage because of their bargaining power against producers, intermediaries, national brands and consumers (Gore and Willoughby, 2018). The intention of raising the question of whether private labels are morally inferior to national ones is to raise awareness of the possible differences between these two types of label and invite consumers to reflect on whether they should or not be buying from private brands, while also to set an ethical base that could possibly trigger political intervention in this matter.

To assess the morality of private brands with respect to national brands, this paper draws on previous philosophical research which analysed questions of moral superiority with reference to food consumption. Primarily, I will use a similar approach to the one developed by Ferguson and Thompson (2021) in assessing local and global foods adapted to private and national brands. In their paper, Ferguson and Thompson construct a debate around local and global food through three core sections in which they compare both food types: sustainability, economics and impact to local community. However, instead of analysing the impact of private and national labels on these aspects, I will be comparing them on the economic effect, both to consumers and producers, sustainability and image and innovation. Unlike the case for local and global food, image and innovation are key components that allow us to distinguish between the two products, while doing so through a local community lens would not add any relevant value. These three aspects are key to retail practices because they do not solely focus on affordability or demand and supply to assess the moral impact of private and national brands. The economics aspect reflects how fairly both producers and consumers are treated, balancing affordable prices for consumers with fair compensation for suppliers. Sustainability highlights the environmental and social responsibility of brands, ensuring that brands contribute to a global sustainable development. Finally, innovation touches on whether brands contribute meaningfully to market development or engage in free-riding by imitating competitors’ intellectual property, and not contributing to the natural development of society, while image reflects on the physical plagiarism of private brands against national brands, undermining the national brands’ efforts in marketing .

For the economics section, I will compare how consumers and producers are affected by private brand’s irruptions in the market and the consequence competitive reaction from national brands. For the sustainability section, I will refer to the market of cocoa, as it is a product that features aspects not only related to climate action but also that makes sure that there is fair trade and that human rights are respected, which will show the differences of the actions taken by national and private brands to mitigate these externalities. For the image and innovation section, I will be using innovation in Spain to illustrate the negative impact of the lack of restrictions on parasitic copying.

Through all these aspects, I will demonstrate that private brands are morally inferior to national brands because of their disregard of sustainable development, with all details that this implies in terms of green development and innovation. Once I have discussed this, I will proceed to explain and further develop two solutions proposed by the EU that work towards the direction of limiting some of the problems arising from private labels.

One of the most prominently discussed differences between private and national brands is the potential differences in price. In many cases, national brands are forced to reduce their prices to be competitive against cheaper private brand alternative products. To achieve this, they need to cut cost, presumably from marketing expenses. Given the fact that the competition of the market does not allow a reduction of investment in marketing as national brands would lose all their competitive advantage in terms of branding, companies will generally opt for either producing for retailers or introducing a lower-cost alternative (Hoch, 1996), which will be worse in terms of quality. This will benefit low-income consumers in a situation of crisis, as they will buy an inferior good (Hoch, 1996), but it is likely to harm producers because of the cost constraints and generate negative labour impact, and negative environmental consequences, as we will see in the next section.

Moreover, research has found that there are other price effects that can have moral impacts. An example of this is research suggesting that retailers may be increasing their own brand prices. To increase their profitability, they include both national brands and their own brand on their shelves, so that national labels attract the consumer, and by setting a slightly lower price, but still higher than its worth, the consumer buys the private label and the retailer makes as much profit as possible from the private brand (Corstjens and Lal, 2000). Another reason to inflate the price of their brand is to improve the brand image, so that it generates more confidence in the buyers, and also generates the mentioned profitability (Geyskens et al. 2023; Gielens et al., 2021; Vahie and Paswan, 2006). This confidence is also increased by creating similar designs, as I will discuss in the section on image and innovation. This shows how private brands can also have a negative impact on consumers by misleading them with very similar images, while having lower standards in either quality, innovation or sustainability.

Even if we suppose the situation in which private brands force national brands to decrease prices, this benefits consumers, but producers are more likely to be economically worse off due to worse living conditions because they will be paying the burden of companies reducing their costs to maintain the same profit margins. It is not easy to reach a conclusion from these two different outcomes as both producers and consumers have basic needs that have to be fulfilled – consumers will want to subsist by buying a cheaper alternative, while producers’ working conditions will be worsened –, so the economics section does not help determine the outcome of my discussion. This happens because both national and private brands prioritise profit over both consumer and producer needs, so trying to maximise profit through damaging producers or consumers, are two equally wrong alternatives.

In the second section, I will compare the differences in sustainability between national and private brands. Given the price difference and the increase of the bargaining power of retailers, there is reason to believe that the source of products is not the same for private labels as the one from national brands. This can happen because of the bargaining power that retailers have over producers, who are not able to defend their rights and therefore agree to non-ideal deals. To analyse sustainability, I will refer to the traceability of cocoa because of the number of problems that its production generates in the countries of origin. Traceable cocoa is considered to be cocoa where companies can verify their origin, and therefore know the environmental impact and the labour conditions, thus preventing many cases of child labour or exploitation.

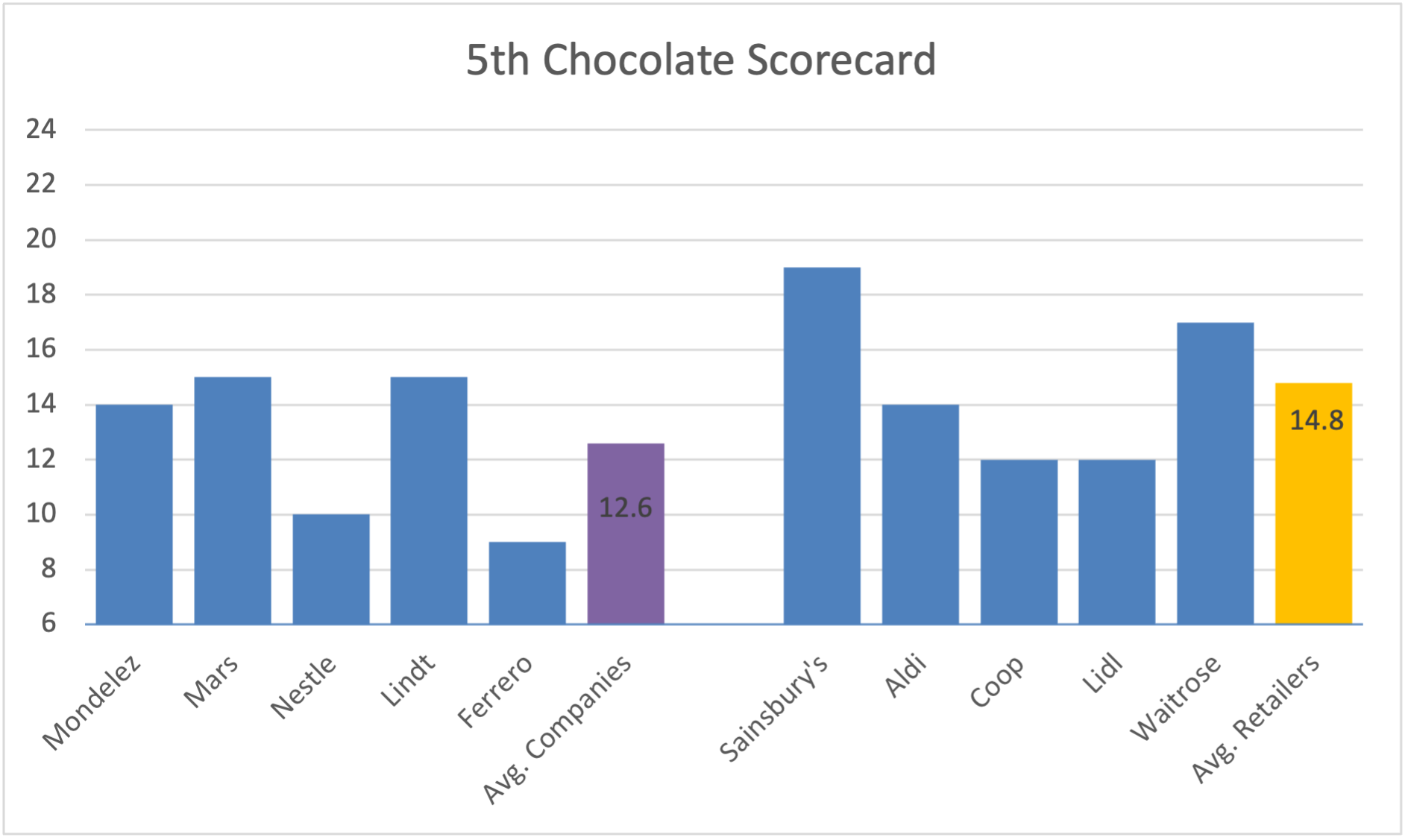

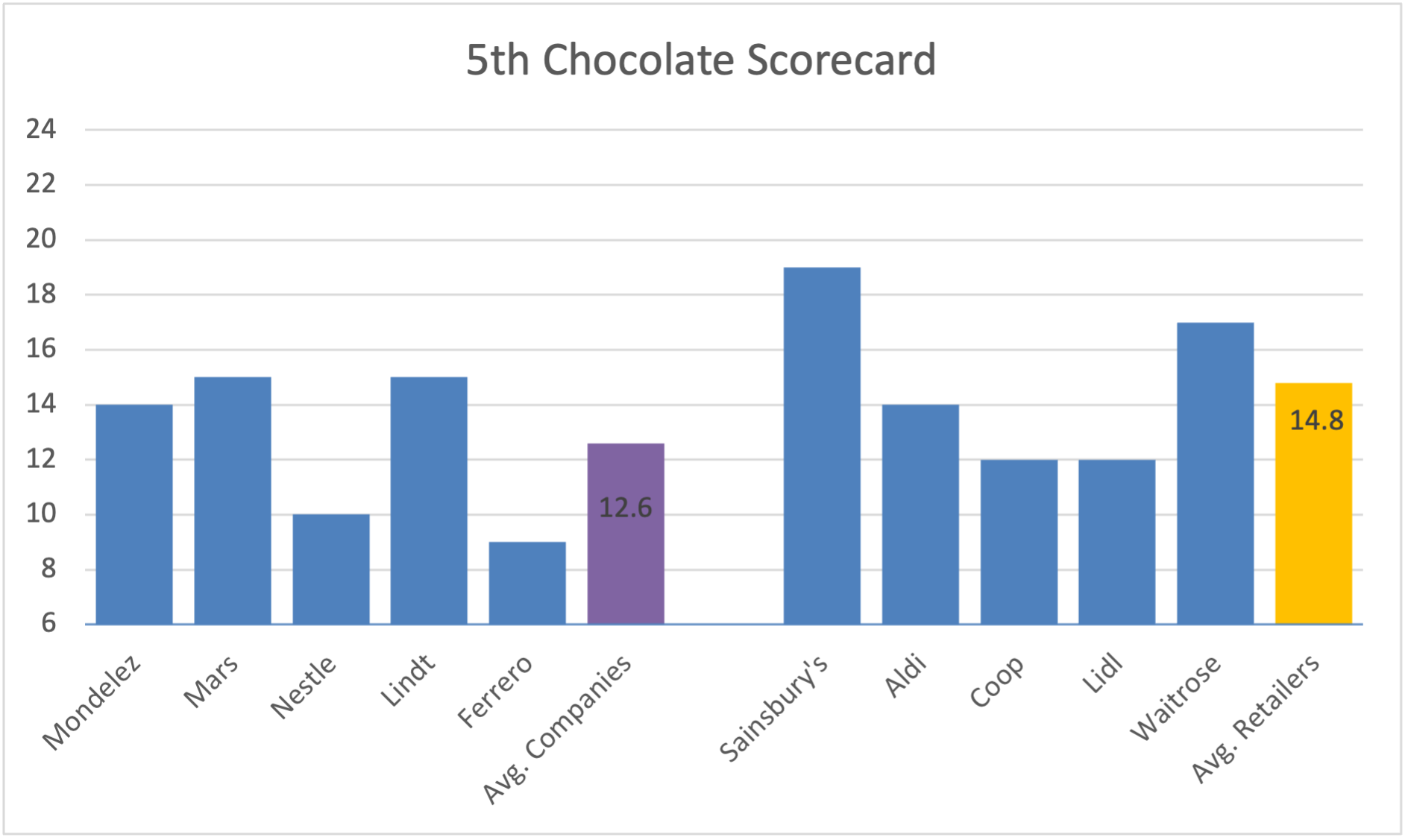

I compared the five largest chocolate companies in the UK in terms of sales: (Móndelez, Mars, Nestlé, Lindt and Ferrero; Global Data, 2021), and the largest five supermarket chains (Sainsbury’s, ALDI, Coop, Lidl and Waitrose). I did not include Tesco, Asda and Morrisons because data was not available. Each company was scored from 1 to 4 in the following categories, where 1 was the best score, and 4 was the worst: traceability and transparency, living income, child labour, deforestation and climate, agroforestry, and pesticides. The best score of 6 can be attained through a score of 1 in all categories and the worst score of 24 can be achieved by scoring 4 in each category (Be Slavery Free et al., 2024). When analysing the largest five retailers and national brands, we see that the average of the chocolate companies is better than the average obtained from retailers. That would show that national brands are doing a better job at achieving sustainability goals.

However, it is true that some retailers are starting to change their attitude and have begun caring about their social responsibility, following a higher awareness of consumers towards the products they consume (Fuller and Grebitus, 2023; Konuk, 2018). In the market of cocoa, this is shown by initiatives such as the Retail Cocoa Collaboration, which notes the intention of the main retailers collaborating to be able to trace cocoa (Scott et al., 2022). This could mean that private brands improve their results in the following years (Gielens et al., 2021), but there is still a lot of improvement to be done, as the OXFAM studies suggest (Vollaard, 2022).

If industries such as the cocoa supply fail to reduce their impact on sustainability or human rights, significant negative consequences will emerge. Private brands often prioritise cost-cutting and market share, which can come at the expense of ethical and sustainable practices. In comparison, national brands tend to invest more in commitments to environmental and social responsibility, making their practices more aligned with positive industry standards.

One of the most common critiques by national brand managers for private brands is that the latter benefit from the investments made by national brands (Larracoechea, cited in Mundi, 2018). In this section, I will consider if there is reason to believe that private brands are morally inferior to national brands because of their lack of innovation and image copying. Despite not influencing directly the most vulnerable parties – consumers and producers – I believe that innovation is crucial in many industries to guarantee progress, and if all companies went on to diminish the spending on innovation, consumers would ultimately be affected when reaching a point in which progress would cease. However, there are pressing needs for innovation, including to transition to a greener society, with packaging solutions that pollute less and are environmentally friendly (European Commission, 2023b) or that offer better products for people with allergies or with special dietary requirements.

The case of Spain illustrates how this decrease of innovation has been noticeable and has started to become a possible threat. During the period from 2010 to 2020, the innovation in Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) levels decreased by 44 per cent (KANTAR, 2020). One way to understand this situation is by looking into private and national brands. In 2019, more than 95 per cent of the innovation was carried out by national brands, while private brands only accounted for the remaining 5 per cent (KANTAR, 2020). Data suggests that the lower the percentage of innovative products of national brands introduced by retailers or supermarkets, the higher the percentage of private brand products sold (ESADE Creapolis, 2018). This results in innovative products not reaching the final consumer. Between 2007 and 2013, the number of national brand products in the main supermarket chains reduced by 16 per cent (ESADE Creapolis, 2018). All this data combined shows that private brands are contributing to the reduction of national brands by not allowing them to enter the supermarket. Instead, they copy innovations that national brands create while not putting the original product on sale. It has been calculated that around 40 per cent of the innovations carried out by national brands are copied within the first year of the launch (ESADE Creapolis, 2018). These two facts demonstrate that even if private labels in some ways pushed national brands to continue innovating (George, 2011), the way in which they do that is not morally appropriate, and the decrease in innovation shows this. In Spain, innovation decreased by around 20 per cent between 2012 and 2015 (KANTAR, 2020). If innovation had not decreased and had remained constant, it would have resulted in the value of the sales of FMCG increasing 5.8 per cent, increasing the GDP by an extra EUR €1.1B (KPMG, 2016). Without the mention decrease in innovation, 2700 people would have been directly employed. Including indirect employment, that number could be approximately around 8100 new jobs (KPMG, 2016). These numbers reflect the impact that the reduction of investment and innovation has on society. Putting together all the data and seeing the attitude that private brands have on innovation indicates that private brands are contributing to a decrease in innovation. Also this misleads consumers as private brands produce a very similar design with a different quality.

Against national brands, it can be argued that the investment in marketing only incentivises overconsumption because beautified designs generate attraction. This argument would seem valid if private brands did not copy their content and focused on providing products without any sort of marketing, but instead, private brands copy even the design and packaging and sell the product at a lower price, with differences in quality, profiting from the similarities, which mislead consumers. This is shown in the case between ALDI and Baby Bellies, in which Hampden Holdings – owners of Baby Bellies – took legal action against ALDI, accusing the German company of copying the design of their snack products (Figure 2). The case is yet to be resolved, but it is unlikely that ALDI will be fined for copying the product (Pattabiraman, 2023).

Both economically and morally, motives seem to point to the fact that private brands are profiting from the innovation carried out by national brands, generating large profits for private brand distributors. I have argued that the lack of innovation will have to be addressed by policymakers with regulations that I will discuss later.

After analysing private and national brands through the economic aspect, sustainability and the image and innovation perspectives, I have concluded that private brands are morally inferior to national brands because they do not offer a clear economic benefit in general, as they benefit consumers but tend to worsen the conditions for primary producers. In terms of sustainability, all insights indicate that private brands put pressure on – or at least do not do enough to support – the ethical production of chocolate. Finally, in terms of creativity and image, I have shown that there are many reasons to believe that there is some wrongness in the way that private brands act, which has been a determinant factor to show the moral wrongness of private brands with respect to national brands.

After answering the main question and arguing that private brands are morally inferior to national brands, I wanted to give some remarks on possible political interventions that would regulate this situation.

One of the ways that the EU has found to limit the sustainability damage caused by some companies is by creating a new law that forces all companies that take products into or out of the EU to be able to prove the product’s origin. This is to demonstrate that the company is not collaborating to damaging the environment and that human rights are enforced during the supply-chain process (European Commission, 2023a). Even if this law does not directly tackle private brands, it will set some minimum standards that should level up sustainability practices of both national and private brands. From the moment of its enforcement in 2025, it should ameliorate the poor results that some companies show – especially retailers seen in the Cocoa Scoreboard (Figure 1). By applying this measure, we might observe a deviation of the offer from the EU to other parts of the world, as companies will be more interested in selling in other locations where less restrictions will be applied. Another result could be an increase in prices because of the lack of appropriate supply and the due diligence that will have to be carried out. This law is very likely to shape the next decade of supply in the EU (Retamales et al., 2023), so it should solve many of the concerns I raised in the sustainability section.

Regarding the issue of the lack of innovation in the EU (European Commission, 2023b), a subsidy has been allocated to incentivise innovation across the consumer goods industry – in this specific case for food products. The subsidy is not directly aimed at private companies, so the issue is not fully resolved with this policy because innovation is still not incentivised enough.

In terms of the image, the EU also proposed the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCDP; European Commission, 2005), which was a European law against practices like parasitic copying or unfair practices from business actors. The main problem with this law, applied in 2005, is the disparity of criteria of different countries in applying the regulation, making plagiarists tackle some countries, depending on the characteristics within the law. Even in countries where this law has been applied more strictly, like Germany, innovator companies have faced some problems in reporting ‘lookalikes’ and getting compensation when their products were not differentiated. Countries like the UK, are even more permissive, and allow these copies to succeed easier (Freeman et al., 2013). This suggests that one of the approaches to take in this sense is to rewrite the UCDP law in a more concise way that leaves less space for interpretation, and ensures that it is applied in a more unified way, which could be done by letting specialist courts take control of the matter (Lovells, 2012). Seeing that even in the most restrictive countries there are still difficulties in applying the regulation, there should be a more restrictive approach to copying and allowing parasitic copies, independently of their reputation in the market.

To sum up, I have answered the question on whether private brands are morally inferior to national brands through their impact on sustainability and image and innovation, while also analysing the impact on economics, which ended up being irrelevant to the outcome of the discussion because of the positive and negative factors. In the last section, I have shown some possible solutions to lessen the wrongs of private brands and make sure there is a fairer approach. As further research, it would be interesting to see what the most appropriate way is of ensuring effective fairness between private and national brands when it comes to sustainability and innovation.

Figure 1: Top five chocolate companies and retailers result in 5th Chocolate Scorecard. Data retrieved from Be Slavery Free et al. (2024). Own Work.

Figure 2: Hampden Holdings v ALDI snacks. Obtained from: Inside FMCG (2023).

Be Slavery Free, Macquarie University, Open University UK & University of Wollogong (2024), ‘5th Chocolate Scorecard. Chocolate Scorecard’, available at https://www.chocolatescorecard.com/scorecards/, accessed 28 April 2024

Corstjens, M. and R. Lal (2000). ‘Building store loyalty through store brands’, Journal of Marketing Research, 37 (3), 281–91.

ESADE Creapolis (2018) ‘Proyecto de investigación’ ESADE. Promarca, available at https://www.promarca-spain.com/estudios/, accessed 26 April 2024

European Commission (2005), ‘Unfair commercial practices directive’, European Commission, available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32005L0029, accessed 30 April 2024

European Commission (2023a), ‘Regulation on deforestation-free products’, European Commission, available at https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/forests/deforestation/regulation-deforestation-free-products_en, accessed 29 April 2024

European Commission (2023b) ‘Food 2030: Green and resilient food systems conference concludes successfully in Brussels’, available at https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/news/all-research-and-innovation-news/food-2030-green-and-resilient-food-systems-conference-concludes-successfully-brussels-2023-12-14_en, accessed 18 June 2024

Ferguson, B. and C. Thompson (2021), ‘Why buy local?’, Journal of Applied Philosophy, 38

Freeman, J. Gibson, J. and P. Thompson (2013), The impact of lookalikes: similar packaging and fast-moving consumer goods. Intellectual Property Office.

Fuller, K. and C. Grebitus (2023), ‘Consumers’ preferences and willingness to pay for coffee sustainability labels’, Agribusiness, 39 (4), 1007–25.

George, D. (2011), Trends in Retail Competition: Private Labels, Brands and Competition Policy. Oxford: Institute of European and Comparative Law.

Geyskens, I., B. Deleersnyder, M. G. Dekimpe and D. Lin (2023), ‘Do consumers benefit from national-brand listings by hard discounters?’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 52, 97–118.

Gielens, K., Y. Ma, A. Namin, R. Sethuraman, R. J. Smith, R. C. Bachtel, and S. Jervis (2021), ‘The future of private labels: Towards a smart private label strategy’, Journal of Retailing, 97 (1), 99–115.

Global Data (2021), ‘The market value (retail sales value) of chocolate industry in United Kingdom (2017 - 2025, USD Millions)’, Global Data, available at https://www.globaldata.com/data-insights/consumer/the-market-value-retail-sales-value-of-chocolate-industry-in-united-kingdom-210449/, accessed 28 April 2024

Gore, T. and R. Willoughby (2018), ‘Ripe for change: Ending human suffering in supermarket supply chains’, OXFAM, available at https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/ripe-for-change-ending-human-suffering-in-supermarket-supply-chains-620418/, accessed 05 February 2024

Hoch, S. J. (1996), ‘How should national brands think about private labels?’ MIT Sloan Management Review, 37 (2), 89

KANTAR (2020), ‘Radar de la Innovación 2020’, Promarca, available at https://www.promarca-spain.com/estudios/, accessed 26 April 2024

Konuk, F. A. (2018). ‘The role of store image, perceived quality, trust and perceived value in predicting consumers’ purchase intentions towards organic private label food’, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 43, 304–10.

KPMG (2016), ‘Impacto económico de la innovación en el sector de Fast Moving Consumer Goods’ Promarca, available at https://www.promarca-spain.com/estudios/, accessed 26 April 2024

Lovells, H. (2012), Study on trade secrets and parasitic copying (look-alikes), MARKT/2010/20/D, prepared for the European Commission (EC) by Hogan Lovells International LLP.

Mundi, C. (2018), ‘La batalla entre las marcas blancas y los fabricantes: «Nos copian y esconden nuestras innovaciones»’, OKDiario available at https://okdiario.com/economia/batalla-marcas-blancas-fabricantes-nos-copian-esconden-nuestras-innovaciones-1845934, accessed 26 April 2024

Pattabiraman, R. (2023), ‘Aldi sued over ‘copycat’ snacks’, Inside FMCG, available at https://insidefmcg.com.au/2023/03/08/aldi-sued-over-copycat-snacks/, accessed 30 June 2024

Retamales, V., A. Alifandi, M. Roberts, T. Acheampong and C. Cardenas (2023), ‘Global impact of the EU’s anti-deforestation law’, S&P Global, available at https://www.spglobal.com/esg/insights/featured/special-editorial/global-impact-of-the-eu-s-anti-deforestation-law, accessed 29 April 2024

Scott, E., E. Nelson, W. Schreiber, S. G. Garret and E. Gorringe (2022), ‘2022 Annual trader assessment result’, Retailer Cocoa Collaboration, available at https://retailercocoacollaboration.com/, accessed 06 March 2024

Sethuraman, R. and C. Cole (1999), ‘Factors influencing the price premiums that consumers pay for national brands over store brands’, Journal of Product & Brand Management, 8 (4), 340–51.

Vahie, A. and A. Paswan (2006), ‘Private label brand image: Its relationship with store image and national brand’, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 34 (1), 67–84.

Vollaard, C. (2022), ‘Mind the gap: Oxfam’s fourth supermarket scorecard explained’, OXFAM, available at https://www.oxfam.org/en/mind-gap-oxfams-fourth-supermarket-scorecard-explained, accessed 04 February 2024

Bargaining Power: The ability of a retailer or producer to influence the terms and conditions of trade to their advantage, often due to their market dominance.

Economic Impact: The study of how different market choices impact producers and consumers, as well as the broader societal implications of these economic interactions.

Fair Trade: A movement and certification focused on ensuring ethical production, fair wages, and sustainable development for producers, particularly in developing countries.

Morally Inferior: Ethically deficient or less justifiable when compared to other alternatives, often due to practices that compromise fairness, sustainability, or social responsibility.

National Brands / Commercial Brands: Brands that are developed, marketed, and sold by manufacturers to a wide range of retailers.

Negative Labour Impact: The adverse effects on workers' conditions and livelihoods, such as wage reductions, job insecurity, poor working environments, or exploitation, often resulting from companies' efforts to cut costs, increase profits, or compete in the market.

Private Brands / Private Labels / Own Brands: Brands owned, controlled, and sold exclusively by retailers, often as alternatives to national or commercial brands. (Sethuraman and Cole, 1999: 340)

Sustainability: Practices that meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs, including environmental, economic, and social aspects.

To cite this paper please use the following details: Oliver I Ribé, A. (2024), 'Are Private Brands Morally Inferior to National Brands?', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 17, Issue 2, https://reinventionjournal.org/index.php/reinvention/article/view/1702/1379. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.