Lucas Huan Zhi Kai, University of Warwick

This article focuses on exploring the securitisation of the Malaysian chicken export ban that took effect on 1 June 2022. The effects of the chicken export ban seemingly went beyond the economics of food, and expanded into the realm of national identity, as the de facto national dish of Singapore got compromised. As food and national identity is intricately linked to societal security and a key part of securitisation theory, this research paper seeks to explore the extent to which the chicken export ban was securitised. Through the use of a frame analysis, three different categories of news media were analysed: governmental media, local news media and foreign news media. The analysis showed that the foreign news media had attempted securitisation, but the local news media and governmental media refrained from securitisation, and rather engaged in a prognostic framing to reframe the chicken export ban into a proactive management of the situation which desecuritised the ban.

Keywords: Securitisation of Food, Societal Security and National Identity, Securitisation Frame Analysis, Malaysian Chicken Export Ban, News Media Securitisation

On 1 June 2022, Malaysia implemented a ban on the export of live chickens to Singapore in response to a domestic shortage that had caused local chicken prices to rise significantly (Chen, 2022). This ban disrupted 34 per cent of Singapore’s total chicken imports, resulting in significant unease regarding food security, food inflation and business uncertainty within the food industry (Moss, 2022). The ban not only impacted the economic landscape but also sparked concerns over the socio-cultural fabric of Singapore (Lin and Chu, 2022), particularly affecting the availability and quality of Singapore’s de facto national dish, chicken rice (Chen, 2022). The repercussions extended beyond economics into political realms, as Singapore diversified its imports and reduced reliance on Malaysian chicken (Gov.sg, 2022). The differing stances between the Singaporean government and media outlets on the severity of the ban’s impacts set the stage for this research. While some news media outlets proclaimed the ban as a crisis and stipulated that Singapore’s national dish was in danger (Chen, 2022), the official stance was that it was inconsequential in the bigger scheme of things (Gov.sg, 2022). Hence, the research seeks to determine whether news media is the main actor of securitisation regarding the chicken export ban in Singapore, and to analyse the resulting securitisation frames. To answer this question, this paper will utilise a frame analysis to understand the framing of the chicken export ban from a securitisation theory standpoint. It finds that, under the topic of food and culture, the assumed traditional actor in securitisation theory, the government, is no longer the sole securitisation actor. Rather, media outlets begin to function as a voice of societal security. This has ramifications on traditional securitisation theory as it refutes the mainstream securitisation theory that the government is the main securitisation actor and opens doors for more research into potential securitisation actors, such as media and news agencies.

Securitisation, developed by Ole Wæver (1993) in what has been framed as part of the wider Copenhagen school of thought, describes that a security issue does not necessarily relate directly to traditional concepts of security or crises. Rather, an issue has to be labelled and described as a security issue or crisis. For an issue to be securitised, it must undergo a process of being labelled as a security threat, thus justifying a bending or breaking of governmental and political rules to an unprecedented level for the purpose of mitigating said threat (Stritzel, 2014). Therefore, under this framework, events need not be initial security threats. Rather, in labelling them as a security threat, they become a security threat and is accepted as such. (Peoples and Vaughan-Williams, 2021). Formally, the steps to securitise an issue include 1) identification of existential threats, 2) emergency actions and 3) effects on relations through breaking free of the rules (Taureck, 2006). Traditionally, such securitisation acts are often from governmental or state actors to allow for emergency measures to take place. An example of such is the securitisation of the climate crisis, in which securitisation was used as a tool of mobilisation to ‘mobilize urgent and unprecedented responses’ to environmental issues (Wæver, 1993: 12).

Food is typically not discussed in securitisation analysis; however, it is an important part of national identity (Ranta and Ichijo, 2022). Hence, if an event can be characterised by its impact on national food, it can be understood through securitisation theory. Securitisation commonly refers to events that concern the survival of the state (Buzan et al., 1998); however, there is also a societal security aspect that is often neglected, which is defined as the ability of a society to maintain its language, culture, religion and customs (Uzun, 2023). The importance of this is explored by Wæver (1993: 15), who states, ‘A state that loses its sovereignty does not survive as a state; a society that loses its identity fears that it will no longer be able to live as itself.’ As further explained by Koczorowski (2010: 45), ‘Food is clearly of cultural importance, hence why culture has made its way into the definition of food security.’ Thus, this distinction of societal security allows for events which are characterised as having national food-related impacts to be securitised, and lets food be a strong topic in securitisation theory.

As news media is a non-traditional securitisation agent, the formal securitisation steps mentioned by Taureck (2006) potentially changes. Without the power to enact emergency actions and affect relations, and being a voice of societal security (Wæver, 1993), securitisation from a news media standpoint would solely look at how media identifies an existential threat within a social-cultural context (Vultee, 2022). This would thus make securitisation easier from a media standpoint as there is no need for formal action and relations to change. Thus, in further investigation of the topic, frame analysis will need to be utilised to study how media frames threats within a social-cultural context.

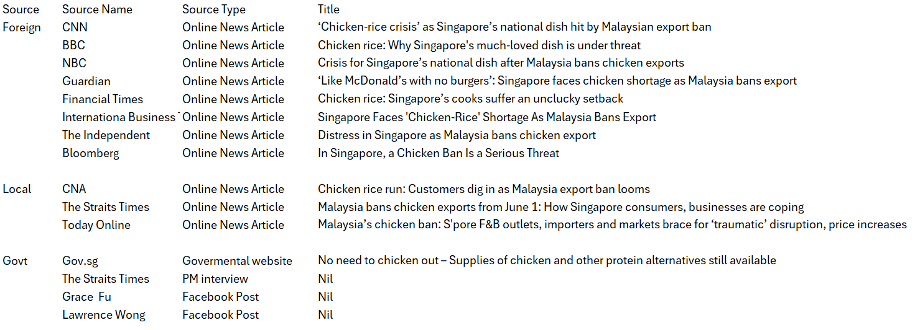

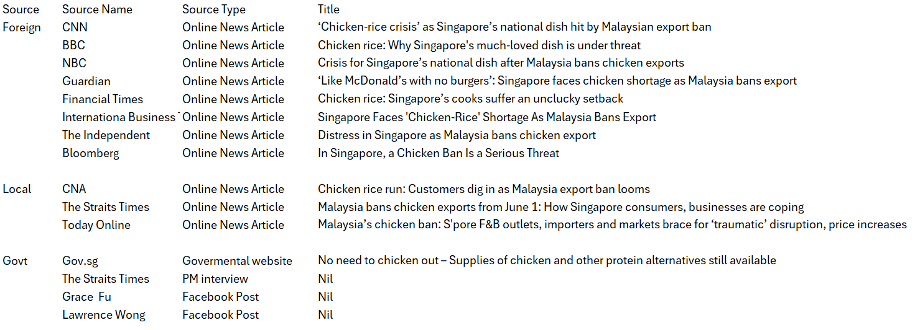

A frame analysis methodology was employed to explore mainstream perspectives about the Malaysian chicken export ban and its effects on Singapore. A frame analysis was chosen over discourse analysis as the focus of the research is to study the portrayal of the chicken export ban. The research examined three different types of securitising news media: governmental, local and international. The news media was studied because the government is the traditional securitisation agent for a nation state, while news media outlets tend to be the informal ‘voice’ or representation of societal security concerns (Wæver, 1993). Moreover, in Singapore, local and state media is under government control and regulation, but foreign media is not; hence, there could be differences in motivation and frames created by local news and foreign news (Infocomm Media Development Authority, 2022). This directed the three different categories of news media studied. In total, 14 online sources were selected, including eight foreign news media, three local news sources and four government media publications (see Appendix 1 for full breakdown). Both local and foreign news media were chosen through an online Google search of the search term ‘Malaysian chicken export ban’. The search term purposely left out leading words such as ‘chicken rice crisis’ or ‘national dish’ to avoid the possibility of skewing the search results towards possible crisis frames. The sources selected were also limited to a week before or after the commencement of the chicken export ban (1 June 2022) to focus on the framing of the effects or potential effects of the ban. The foreign and local media sources selected were different articles from different newspapers. They included well-known media outlets such as Channel News Asia (CNA), The Straits Times, Cable News Network (CNN) and the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), and aimed to explore a wide range of potential frames from different newspapers. For the governmental media publications, due to the distinct lack of published articles except for a guidance published on Gov.sg (2022), the governmental website, other forms of publications were selected. This included a brief media interview by then Prime Minister (PM) Lee Hsien Loong, which was taken from a broadcast in The Straits Times of his response, and Facebook posts by current Prime Minister Lawrence Wong, and Minister of Sustainability and Environment, Grace Fu.

The first part of the research was a frame analysis of the different categories of news media. The second part of the research involved a comparison of the different frames across the three categories of news media. The comparison was conducted in respect to the securitisation framework as previously explained, with the aim of identifying the different frames and determining any coherence or alignment between them.

The chicken export ban was framed by foreign news media as a crisis to Singapore’s national dish, chicken rice. The focus of all the foreign news media was on the chicken export ban, and how it has caused Singapore to ‘face a shortage of “chicken-rice” supplies’ (Ong, D, 2022). Some foreign media outlets opted to utilise a price analysis, detailing that chicken ‘traders warn […] poultry products are expected to see a sharp rise from $3 to $4 or $5 per bird’ (Ong, K. J, 2022) to show an expected price rise in chicken cost. Other outlets, like National Broadcasting Channel (NBC), used interviews with chicken rice business owners to show that the price rise from the ban would affect their business performance. An example used by NBC is Daniel Tan, an owner of seven chicken rice stores, who said that ‘Malaysia’s ban will be “catastrophic” for [chicken rice] vendors like him[self]’ (National Broadcasting Company, 2022). Moreover, the foreign news media also highlight that the rising cost of chicken would have a detrimental effect on the quality or availability of chicken rice. The Guardian cited that some chicken rice businesses ‘would stop serving chicken dishes if it could not get fresh supplies’ due to the export ban (Ratcliffe, 2022), while the Financial Times (2022) resigned Singapore’s cooks to ‘embrace chilled chickens’ over fresh chicken. Thus, the foreign media framed the chicken export ban as a crisis for chicken rice in Singapore.

It is possible to explore this as a societal securitisation issue as Singapore’s chicken rice is seen as Singapore’s national dish, thus allowing the crisis narrative to be extended from chicken rice to Singapore’s societal security. The foreign news media highlighted the importance of chicken rice to Singaporeans and their national identity. Through metaphors, The Guardian and the BBC respectively likened the absence of chicken rice in Singapore to ‘McDonald’s with no burgers’ (Ratcliffe, 2022) or ‘not having pizza in New York’ (Liang and Cai, 2022), suggesting that chicken rice is an essential part of the Singaporean identity. Moreover, many of the foreign news media, including NBC and CNN, explicitly referred to chicken rice as the ‘city-state’s de facto national dish’ (Chen, 2022), further reinforcing the idea that chicken rice is part of the national identity. In fact, it was also made clear that the quality of chicken rice in Singapore is also a source of national identity, as CNN quoted a hawker saying ‘Frozen chicken? […] It will not taste good [… if] you’re happy with that kind of quality, you might as well go to Malaysia’ (Chen, 2022). This reflects the underlying debate over which country, Singapore or Malaysia, has better food, and shows that the high quality of chicken rice is a source of national pride for Singaporeans. Thus, by linking chicken rice to the national identity of Singapore, foreign news media has taken their crisis frame for chicken rice and extended it into a crisis for Singapore’s national identity, and thus securitising the Malaysian chicken export ban for its impacts on Singapore national identity.

The local news media covered the same crisis that Singapore and its chicken supply chain was undergoing. They explored many different perspectives on the ban, avoided prognostic framing, and instead focused on redefining the diagnostic frame of the issue by highlighting two contrasting points: that the chicken export ban significantly affected Singapore, and that it did not.

Local news media highlighted the negative impacts of the chicken export ban and framed it as a challenging situation. However, they did it without referring to chicken rice as a national food. CNA underscores this with bold section headers such as ‘NO POINT REMAINING OPEN’ and ‘“NO CHOICE” BUT TO SELL FROZEN CHICKEN’ (Yeoh, 2022), while Today Online uses ‘S’pore F&B outlets, importers and markets brace for “traumatic” disruption, price increases’ instead (Lee and Zalizan, 2022). The local news media also uses quantifiable evidence, like comparing specific prices of chicken before and after the ban, to substantiate this impact (Heng et al., 2022). This approach creates a diagnostic frame that portrays the chicken export ban as a problem creating significant challenges. The narrative is further enriched by personal interviews conducted by all three news outlets in wet markets – a distinctive part of Singapore’s heritage – using ethos to engage the reader and reinforce the current frame. All this is done, however, without engaging with chicken rice as a dish symbolic of national identity.

However, articles then typically shift towards a frame of normalcy or adaptability. CNA depicts a vivid scene of normalcy: ‘well-stocked displays and a lack of queues at some wet market stalls’ (Yeoh, 2022). This introduces the idea that business is as usual. This idea is maintained throughout the articles by bringing up adaptability or pre-emptive protective actions that the businesses or government is doing whenever detrimental effects on the poultry market is mentioned in the articles. This technique instils a sense of normalcy, and that the challenges could be overcome. For instance, the CNA article mentions business owners contemplating shutting down due to the chicken shortage, which is then contrasted with descriptions of fully stocked displays over several consecutive days (Yeoh, 2022). This is similar in The Straits Times article, where they cite that ‘some chicken rice hawkers said they plan to sell different dishes or use frozen chicken to continue making a living’, after discussing how the export ban has raised chicken prices (Heng et al., 2022). This further supports the running theme of business as usual and effectively creates a script that runs parallel to the previous narrative. Today Online follows a similar dual narrative (Lee and Zalizan, 2022), undermining their narrative of trouble by constantly highlighting the steps being taken to mitigate it, thus framing the export ban as a challenge rather than a crisis. By weaving in how companies are increasing chicken production, slow price adjustments to avoid significant impacts and expanding of the chicken import market in Singapore, all these steps highlight the resilience of the Singaporean consumer and retail market and emphasise that the chicken export ban poses challenges that can be overcome. Furthermore, by briefly mentioning the Singapore Food Agency and summarising the actions taken to address the export ban, all three articles portray the government as reliable and effective (Heng et al., 2022; Lee and Zalizan, 2022; Yeoh, 2022). By introducing these government actions in the context setup, the articles reminded readers of government role each time the dual narratives conflict, highlighting the government’s role in maintaining the status quo. Hence, both narratives work together to establish a frame of normalcy or challenge within the situation and undermine the crisis frame presented earlier.

By presenting these two contrasting diagnostic frames, local news media appeared to try to maintain impartiality in its reporting, acknowledging the complexity of the situation and its varied effects. However, narrative structure used to convey the frame of normalcy serves to undermine the frame of challenge imposed by the chicken export ban. By depicting a minimised impact and following comments about the challenges from the export ban, the local news media enforces a frame of normalcy and casts the crisis frame in an exaggerated light. This was perfectly encapsulated in the final line of the CNA article, a quote from a passerby in the supermarket: ‘Still got so much chicken. Why people say don’t have? [sic]’. Through this framing, local news media appears to diagnostically reframe the chicken export ban into one of business as usual and normalcy (Yeoh, 2022).

Singapore’s then Prime Minister Lee’s response to a question about the chicken shortage in Singapore, taken from a broadcast by The Straits Times (2022) is a good representation of the governmental framing. He provided a succinct and direct answer that underscored the government’s stance on the issue, offering both diagnostic and prognostic framing (refer to Appendix 2 for transcript) In a six-sentence response, PM Lee addressed two main points: one advocating proactive management to handle the situation, and another suggesting that the situation has been exaggerated. This frame is carried on by all members and organisation of the government, such as the current Prime Minister, Lawrence Wong, Minister Grace Fu and the key agency for food, Singapore Food Agency.

This aspect is emphasised throughout all governmental sources. PM Lee provided a prognostic frame by stressing that the government’s response involves proactive management (The Straits Times, 2022). He highlighted this through the use of a contrasting sentence, ‘The answer is not what we do now, but what we have been doing’, and reinforced it with a conditional clause, ‘if any single source is interrupted, we are not unduly affected’. This message is reiterated through the repetition of phrases such as ‘provided’, ‘build up’, and ‘diversify’, active verbs that underscore Singapore’s longstanding strategies. By consistently focusing on this theme, PM Lee portrays Singapore as an active and capable participant in its own governance. The significance of his message lies in his avoidance of any sort of securitisation, refraining from using any form of ‘crisis’ or ‘emergency’ and rather opting to focus on how Singapore is proactively managing the situation. A similar message is repeated in PM Wong’s and Minister Fu’s Facebook posts (see Appendices 3 and 4) and the government website (Gov.sg, 2022), all highlighting the active steps that Singapore was taking, such as growing local and diversifying food sources, and crucially refraining from, or highlighting the absence of, any sort of security speech acts. This cohesive frame is constantly repeated throughout the government’s narrative, suggesting that the chicken export ban has been planned for, and that the whole of Singapore’s government are on the same page in proactively mitigating the situation.

Former PM Lee also transformed the diagnostic frame of the situation by minimising the effects of the export ban and placing it within a broader global context. Concluding his response, he acknowledges the ban’s impact, such as increased cost of living and food inflation, but partly attributes these to broader, ongoing global instability. He states, ‘It is a very unsettled world […] but in the scheme of things, many more disruptive events can occur [than the chicken export ban].’ Minister Grace Fu follows a similar tone by referring to the global situation, and their use of concessive syntax, such as ‘not be able to completely mitigate the disruptions’, acknowledges the nature of the world and yet downplays the current crisis as a minor issue within a global context, encouraging a perspective that the situation could be worse. PM Wong carries out this framing in another manner. In his Facebook post, he uses a photo of himself in a food court, eating chicken rice after the chicken export ban took effect. This has the effect of portraying the situation as business per usual, nothing has changed. Moreover, in his caption, he uses ‘occasional disruptions’ – not even choosing to highlight the chicken export ban in particular but focusing instead on Singapore’s need to be strong and work together to face ‘occasional disruptions’.

This response by Singapore’s leaders is significant as it seeks to reframe and transform the current narrative. By emphasising proactivity, Singapore is not a victim but a proactive actor in addressing its challenges. Moreover, by omitting any reference to food, cultural identity or chicken rice, the leaders detract from the potential securitisation of the issue, instead promoting a global economic perspective on the situation through the diversification of supply chains and Singapore’s active engagement.

This research aimed to determine whether news media is the main actor of securitisation regarding the chicken export ban in Singapore, and to analyse the resulting securitisation frames. Utilising the securitisation framework, the study analysed three distinct frames from governmental, local and external news sources to identify any references to security or crisis. As seen from the three different analyses, the media sources each present distinct frames. Notably, foreign media seem to engage in securitising speech by portraying an economic crisis that impacts the Singaporean way of life, linking this to the national identity associated with chicken rice and thus framing it as a societal crisis. In contrast, the governmental frame adopts a stance of desecuritisation and stability. By highlighting Singapore’s proactive measures and situating these within the broader context of global instability, the government aims to transform the frame, diagnosing the situation as purely economic. The absence of a securitisation speech act serves to desecuritise the situation, helping to alleviate concerns amid perceived threats to societal security. Interestingly, the local media adopts a neutral stance, recognising both sides of the argument but not explicitly using the terms ‘crisis’ and ‘national identity’. Nonetheless, their coverage aligns more closely with the governmental narrative, promoting a frame of normalcy and business as usual, which implicitly supports desecuritisation. The stance of local media is unsurprising because state media is under government control and regulation (Infocomm Media Development Authority, 2022), and hence it is understandable that local media and the government’s narratives are closely aligned, emphasising normalcy and the stability of the situation. This frame alignment amplifies reassurance to the public that everything is under control. External media portrayal of the chicken export ban starkly contrasts with that of local news media and the government, framing it as an economic issue with metaphysical and political implications for Singapore’s identity. Conversely, the government and local news media depict it as a purely economic issue that can be managed by diversifying trade to reduce over-reliance. Therefore, there was a securitisation of the chicken export ban, but only by external news media, and not by local news media or governmental media.

The findings reveal that only the external news media engaged in a securitisation speech act, clearly linking the ban to its effects on Singapore culture and national identity. In contrast, both the local news media and the government adopted a desecuritisation approach, deliberately shifting the focus away from national identity and reframing the situation to avoid the portrayal of a crisis. These results also have an interesting implication for securitisation theory. Traditionally, securitisation speech act has always been limited to the governmental actor, where the government uses it to justify immediate drastic actions (Wæver, 1993). However, in this case, a role reversal occurs, where external media is the securitising actor, while the government is the desecuritising actor. This raises the question on whether such cases could be more prevalent when studying the securitisation of societal security, as societal security does not have its own ‘voice’ (Uzun, 2023), and must rely on actors that represent society, such as news or social media, to voice out relevant concerns (Wæver, 1993).

For an issue to be considered a security concern, it must not only be represented as such but also be widely accepted as such (Buzan et al., 1998). This study is limited in its focus on the representation of the Malaysian chicken export ban, rather than its acceptance, omitting a crucial aspect of the debate and leaving room for further exploration. Future research could consider why external media adopts a different stance from local news media and governmental media, which was not done in this paper. Possibly, being independent of Singaporean state control, they may be driven by different agendas, whether those are related to their affiliations or a desire to attract more viewers with sensational headlines. Lastly, because of its limited scope, the research aimed to identify cohesive frames in the various groups identified and did not have time to delve into the differences in framing within each group, leaving more areas for future research.

The answer is not what we do now, but what we have been doing, now, for several years, which has been to provide, build up our buffer stocks and our resilience, and diversify our sources. So that if any single source is interrupted, we are not unduly affected. And if you can’t buy chicken from one place, well, you can get chicken from other countries. And this time is chicken, next time maybe something else. It is a very unsettled world and inflation is a problem, cost of living is a problem. But in the scheme of things, many more disruptive things can happen than some price adjustments, and we are seeing some of that now.

Transcribed from: THE STRAITS TIMES. 2022. ‘This Time It’s Chicken, Next Time It May Be Something Else’: PM Lee | THE BIG STORY [Online], available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j26mBnlMz9k&t=196s, accessed on 21 February 2024

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=563338605151623&id=100044264657476&set=a.258648418953978, accessed on 21 February 2024

https://www.facebook.com/gracefu.hy/posts/malaysia-has-announced-a-suspension-on-the-export-of-chickens-from-1-june-while-/575084437310629/, accessed on 24 February 2024

Buzan, B., O. Wæver. and J. De Wilde (1998), Security: A New Framework for Analysis, Lynne Rienner Pub.

Chen, H (2022), ‘‘Chicken-rice crisis’ as Singapore’s national dish hit by Malaysian export ban’, Cable News Network, available at https://edition.cnn.com/2022/06/02/asia/singapore-chicken-shortage-malaysia-export-ban-intl-hnk/index.html, accessed 21 June 2024

Financial Times (2022), ‘Chicken rice: Singapore’s cooks suffer an unclucky setback’, Available at https://www.ft.com/content/4bd7e1db-d5e0-4d79-b235-3c978dcc5648, accessed 23 June 2024

Gov.sg (2022), ‘No need to chicken out – Supplies of chicken and other protein alternatives still available’, available at https://www.gov.sg/article/no-need-to-chicken-out-supplies-of-chicken-and-other-protein-alternatives-still-available, accessed 23 June 2024

Heng, M., D. Loke. and R. Goh (2022), ‘Chicken rice sellers raise prices, plan to sell other dishes to cope with lower supply of fresh chicken’, available at https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/malaysia-bans-chicken-exports-from-june-1-how-singapore-consumers-businesses-are-coping, accessed 23 June 2024

Independent. (2022), ‘Distress in Singapore as Malaysia bans chicken export’, available at https://www.independent.co.uk/news/singapore-ap-malaysia-kuala-lumpur-ukraine-b2090787.html, accessed 23 June 2024

Infocomm Media Development Authority. (2022), ‘Online News Licensing Scheme (ONLS) – Computer online service licence’, Infocomm Media Development Authority, available at https://www.imda.gov.sg/regulations-and-licensing-listing/online-news-licensing-scheme, accessed 21 February 2024

Koczorowski, C. Z. (2010), ‘Unpacking food security: Is there shelf space for food in security studies?’, Inquiry and Insight, 3 (1), 38–61

Lee, L. and T. Zalizan (2022), ‘Malaysia’s chicken ban: S’pore F&B outlets, importers and markets brace for ‘traumatic’ disruption, price increases’, Today Online, available at https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/malaysia-chicken-ban-fb-importers-markets-disruption-price-increases-1906546, accessed 23 June 2024

Liang, A. and D. Cai (2022), ‘Chicken rice: Why Singapore’s much-loved dish is under threat’, BBC, available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-61589222, accessed 23 June 2024

Lin, C. and M. Chu (2022), ‘Singapore’s de-facto national dish in the crossfire as Malaysia bans chicken exports’, Reuters. Available at https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/singapores-de-facto-national-dish-crossfire-malaysia-bans-chicken-exports-2022-06-01/, accessed 21 Febuary 2024

Moss, D. (2022), ‘In Singapore, a chicken ban is a serious threat’, Bloomberg, available at https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-05-30/malaysia-s-chicken-ban-raises-food-security-inflation-fears-in-singapore?leadSource=uverify%20wall, accessed 21 Febuary 2024

National Broadcasting Company. (2022), ‘Crisis for Singapore’s national dish after Malaysia bans chicken exports’, NBC News, available at https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/crisis-singapores-national-dish-malaysia-bans-chicken-exports-rcna31785, accessed 23 June 2024

Ong, D. (2022), ‘Singapore faces ‘chicken-rice’ shortage as Malaysia bans export’, International Business Times, available at https://www.ibtimes.com/singapore-faces-chicken-rice-shortage-malaysia-bans-export-3529174, accessed 23 June 2024

Ong, K. J. (2022), ‘Commentary: Ruckus over Malaysia chicken export ban justified in food paradise like Singapore’, Channel News Asia, available at https://www.channelnewsasia.com/commentary/malaysia-chicken-export-ban-singapore-food-expensive-2739346, accessed 21 Febuary 2024

Peoples, C. and N. Vaughan-Williams (2021), Critical Security Studies: An Introduction, Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge.

Ranta, R. and A. Ichijo (2022), ‘Food, national identity and nationalism’: From Everyday to Global Politics, Springer.

Ratcliffe, R. (2022), ‘‘Like McDonald’s with no burgers’: Singapore faces chicken shortage as Malaysia bans export’, The Guardian, available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jun/01/like-mcdonalds-with-no-burgers-singapore-faces-chicken-shortage-as-malaysia-bans-export, accessed 23 June 2024

Stritzel, H. (2014), ‘Securitization theory and the Copenhagen school’, in their Security in Translation: Securitization Theory and the Localization of Threat. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Taureck, R. (2006), ‘Securitization theory and securitization studies’. Journal of International Relations and Development, 9, 53–61.

The Straits Times. (2022), ‘This time it’s chicken, next time it may be something else’: PM Lee | THE BIG STORY’, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j26mBnlMz9k&t=196s, accessed 21 February 2024

Uzun, Ö. S. (2023), ‘Societal identity and security’, in Romaniuk, S. N. and P. N. Marton (eds.) The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Global Security Studies. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Vultee, F. (2022), A Media Framing Approach to Securitization: Storytelling in Conflict, Crisis and Threat (1st ed.). Routledge.

Wæver, O. (1993), ‘Securitization and Desecuritization’, in Lipschutz, R. D. (ed.) On Security. Columbia University Press.

Yeoh, G. (2022), ‘No queues, panic buying or lack of chicken: A quiet first day of Malaysia’s export ban for some wet markets’, Channel News Asia, available at https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/malaysia-chicken-export-ban-wet-markets-supply-no-queues-panic-buying-2718046, accessed 8 May 2024.

Copenhagen School of Thought: An approach to security studies that argues that security is not an objective condition, but a process in which public actors transfroms issues into security matters, commonly through public discourse and the speech of declaring an issue as a threat.

Food Security: A state in which people, have at all times, access to sufficient, safe and nutrious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences.

Frame Analysis: A social science research method that focuses on how certain issues are presented by media or public figures, and what is the resulting influence on public perception and behaviour.

Prognostic framing: A component of frame analysis. It refers a frame that outlines potential solutions or approaches to overcome a challenge, often used in a context of social movements or policy challenges.

Securitisation: A process important to the Copanhagen School of Thought, where issues are transfromed into urgent security concerns when a political actor identifies an existantial threat the requires extraordinary measures.

Securitisation Frames: Refers to frames produced by media or public figures that represents issues as an existantial security threat necessitating extraordinary measures.

Securitisation Framework: The overarching framework introduced by the Copahagen School of Thought which encompasses the analysis of actors involved, the speech acts used, and the socio-political context in which securitisation occurs.

Securitisation Speech Act: A key concept in the Copahagen School of Thought which refers to the act of declaring an issue to be an existantial security threat through speech or discourse.

Wet Market: A type of marketplace typical in Singapore where fresh produce such as fruits, vegetables and meat are sold. The name “Wet Market” is derived from the frequent washing of floors for hygiene purposes.

To cite this paper please use the following details: Huan Zhi Kai, L. (2024), 'To What Extent Were There Attempts to Securitise the Malaysian Chicken Export Ban In Singapore? A Comparative Analysis of Frames Between Government and News Media', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 17, Issue 2, https://reinventionjournal.org/index.php/reinvention/article/view/1700/1374. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.