Ayu Larasati, Monash University, Australia

Tom Zundel, University of Warwick

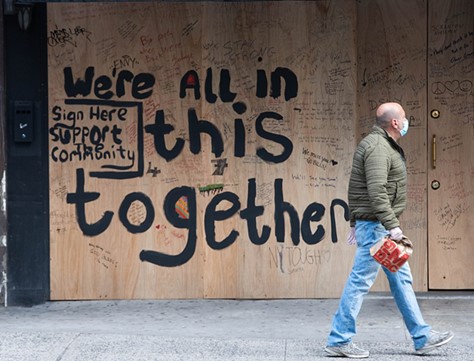

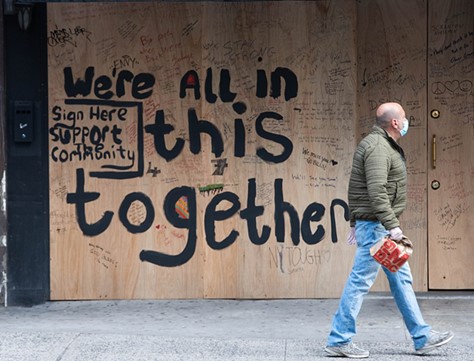

Under the frustration of continued lockdowns, people engaged in small ways of securing happiness and wellbeing, such as learning new skills and hobbies, meditating and streaming movies. They said we all fought together in the shared struggle to defeat the virus. But were we all really in this together? Or were large swathes of society left forgotten?

Adverse effects on mental health have been widely noticed within the last three years as a significant repercussion of living through COVID-19. The World Health Organisation (WHO, 2022) reports an increase in the incidence of depression and anxiety by a quarter of the population studied. This has posed urgency in laying a global mental health agenda while indicating various notions of mental health problems. Different anxiety triggers are involved, predominantly concerning health and safety (the fear of being infected), financial insecurity, and low social interactions (Belot et al., 2021). While these are apparent for all societal identities, the experiences of the working population across socio-economic backgrounds may elucidate particular nuances that inform the flaws in mental health treatment within capitalist structures. This article thus intends to discuss how mental health is shaped by economic status during the pandemic – in the sense of acknowledging the mental health experiences of the wealthy while alienating those of the poor.

Many contend that the mounting pandemic worries mean greater recognition of the fatality of mental illness. In Indonesia, for example, increased awareness and destigmatisation of mental health illness have gradually occurred, making people more willing to discuss their wellbeing (Citraningtyas, 2020). Moreover, some workers have reassessed their exploitative way of working and, for those who can, decided not to let work ‘dominate their lives’ by considering work–life balance (Wahlquist, 2022). This may indicate the reconfiguration of workers’ agency and set out mental healthcare prioritisation on the table.

Nevertheless, even when mental health measures were relatively taken from the early pandemic phase, inequalities have prevailed in which interventions seem to favour the more prosperous. This manifests in the lack of access to equitable care services. The offered solution often deals with counselling, anxiety management or meditation services that many have been conducted via call or online due to lockdowns. Besides the quantity issue of mental health specialists, these care services also tend to be out of reach for low-income people (Burgess, 2020). Most importantly, governments and corporations have also crafted prominent discourses around coping with stay-at-home policies that construct how those in the high-middle income class redefine comfort (Sobande, 2023). This partly takes shape in the pandemic home lifestyle and a certain degree of consumption, signalling the effort to sustain neoliberal capitalism in the COVID-19 era.

Discussing inequalities in COVID-19 mental health will need to draw in the initial organising of mental health problems that appear to be a challenge for the capitalist system. As explained by Moncrieff (2022), this is because workers suffering from mental illness cannot be financially productive, impeding the capitalists’ ambition of gaining surplus and exchange value. Using the Marxist perspective, psychological issues thus have been indebted to an individual’s responsibility. Consequently, the mental health treatment system has been introduced, where wellbeing issues are medicalised, reifying the responsibility to individuals (Carr, 2022). This reveals the entanglement of class structures, where mental health can be weaponised to define and distribute access unevenly. As follows, this paper’s economic takes will not do justice to the depth of class structures and their knot with mental health inequalities, but it can peel the outer layer of exposure to the lopsided scale.

First, the relevance of wealth factors in determining the impact of COVID-19 on mental health is evident in housing. Living in a high-poverty neighbourhood or district significantly affected those whose mental health worsened during 2020 (Pierce, 2021). Furthermore, even the quality and size of accommodation features in pandemic mental health as around 12 per cent of British households have no shared or private garden, limiting their ability to go outside yet further and isolating individuals more (Marshall et al., 2020). As such, it is no surprise that those living in rented accommodations are at higher risk of psychiatric disorders than owner-occupiers (Henderson et al., 1998).

Depending on financial circumstances, such a divide is further evidenced by income and employment. There is a link between higher income inequality and an increased risk of mental distress and disorders (Burns, 2015). Part of this is due to the labour market. Class features prominently in the labour market, with jobs often segmented on the grounds of educational attainment, which restricts those from predominantly poor backgrounds to lower wages and insecure employment, while those with high incomes typically face better working conditions and job security (Fenwick and Tausig, 2007). The impact on mental health can be noted by those in low-skill employment having few alternatives when laid off with scarcer job opportunities than those with higher educational requirements (Wang et al., 2015), exacerbating the stress of job loss during the pandemic for those on low salaries.

Furthermore, the link between unemployment and mental health is particularly strong, with poverty and unemployment found to contribute to more prolonged episodes of mental health disorders (Weich and Lewis, 1998). Part of this is due to the benefits of employment compared to unemployment. Being employed and having a job contributes positively to mental health and alleviates depression by providing greater economic independence, self-esteem and more (Honkonen et al., 2007). As such, those unemployed suffer comparatively to those better off.

The problem is that, as established, support is hard to reach for those worse off. Only a third of people seeking mental health support can access the help they need, with those who need the most help often facing the most significant barriers to accessing support (Health, 2020). Also, mental health services that were already stretched pre-pandemic have suffered worldwide due to the COVID-induced backlog in healthcare systems (Marshall et al., 2020). This in no way means high-income individuals do not suffer from mental health problems, nor that the pandemic did not impact these people, merely that the distributional toll was concentrated most heavily towards those at the bottom. As such, the ability for those who need help to get it is limited and only those who can go private – which is those better off with enough disposable income – can reliably get support. This embeds into society a clear class divide concerning mental health, with those on lower incomes suffering worse during COVID-19 while simultaneously finding it harder to reach the support they need.

Along with the technical side of mental health interventions, the implantation of the ideas of care in public conversations is another crucial avenue to recognise. This is because it connotes the rhetorical level of mental health treatment, leading to the everyday stress coping mechanism that risks mental health inequalities being disguised. Figuring out new ways of caring and feeling comfortable was the common theme of pandemic survival to redefine the new normal. Notably, there has been an ‘explosion of care’ to ensure sanity (Chatzidakis and Littler, 2022: 269). For instance, the central messages the state and social institutions shared revolved around a sense of togetherness and keeping calm, like the globally popular hashtags #QuarantineAndChill or the local hashtags Australia’s #InThisTogether (Mumbrella, 2021) and Indonesia’s #IndonesiaCertainlyCan (Indra, 2021).

Despite the supportive intention, the narratives seem to contradict neoliberalism’s core of productivity and competitiveness, denoting adaptive reactions from the capitalist system to remain in control. These can be reflected by the immense involvement of brands in constructing care discourses. Several scholars have investigated the typologies of brand messaging during COVID-19 that emphasise the importance of solidarity in fighting the virus (Chatzidakis and Littler, 2022; Sobande, 2023; Starr et al., 2022). Some brands, like Dettol UK’s #BackToWork and Apple’s ‘The Whole Working From Home’ ads (Apple, 2020; McGonagle, 2020), attach their product messaging to hygiene maintenance and the hassle of working from home experience. Alternatively, an Indonesian travel booking brand Traveloka promotes the urban lifestyle as a solution to pandemic boredom, like a ‘Smart Staycation’ with cleanliness guaranteed (Traveloka, n.d.).

In the marketing language, this approach may be helpful for brands to stay relevant amid changing spending habits, but it significantly also advances consumption, exacerbating inequalities in mental health treatment. Brands joining the bandwagon to manage daily pandemic anxiety demonstrate the process of commodification by using care as a ‘mere commodity to aid commercial activities’ (Sobande, 2023: 6). Although the above examples apply different messaging frames, both similarly induce consumption as the manifestation of care. Aligned with the true intention of capitalism, this measure is more to optimise productivity rather than to calm the mind by navigating work in the new normal so that much work is still accomplished (Starr et al., 2022). Furthermore, the ads’ depiction of care and comfort may only represent the needs and experiences of the affluent. The partial nuances of stressors, the activity types and the proposed solutions ignore the varying levels of risk experienced by those who have no privilege to escape from the discomfort, like low-waged labours (Starr et al., 2022).

This illuminates the intersection of economic means with mental health inequalities that are systemic and hegemonic. Brands taking advantage of the needs of solidarity only treated people as consumers. Therefore, their messages around everyday wellbeing and suggested remedies targeted those with higher buying power, showcasing ignorance of the poor. The problem is that these narratives shade the most harm endured by those less privileged in coping with financial-based mental distress. Relating to the previous section, this isolation only obstructs the provision of equitable mental health support, leaving the mental health issues of the poor unacknowledged and unaddressed.

In conclusion, COVID-19 and the lockdowns have changed much of society’s stigma around mental health, with the issue now more prominent than ever in public discourse. However, it has also shone a light on the divide in mental health along economic capital that the pandemic triggered. Most importantly, this research has revealed the degree to which mental health is deeply interwoven with the existing regime of global capitalism and neoliberalism. Those with insecure jobs and housing relatively suffered greater anxiety and depression than those with greater financial stability. Furthermore, these individuals struggle to find adequate support as public healthcare lags in providing mental health treatment compared to physical health, and the pandemic disrupted much of what was provided. The circumstances were more problematic as those in power substantially tainted the understanding of mental health care. To facilitate the commercial motives, portraying everyday stress and promoting consumption under the banner of care eliminated the low incomes from the picture. As such, the low incomes were forced to deal with their concerns themselves, while those with greater resources could access privately provided healthcare instead, if not home-based leisure.

This serious divide risks embedding mental health on a basis of wealth for the foreseeable future without significant investment and care given to providing treatment available to all. Several groups are trying to bridge this gap, with the British Psychological Society campaigning for social class to be protected under the 2010 Equalities Act to tackle class-associated poor mental health (BPS Communications, 2022). However, it remains to be seen how effective these efforts will be in shaping public opinion and government action. Crucially, as scholarship has also started to disclose (see Sobande, 2023), diving into the intersection of mental health and other class dimensions, like race and ethnicity, will be helpful for further exploration of this issue to ensure a more holistic view in capturing mental health in(ex)clusions.

Figure 1: We’re all in this together. A ‘We’re all in this together’ mural on the wall of a New York restaurant captured by Anthony Quintano in April 2020. This image is licensed by Creative Commons 2.0, taken via Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Restaurant_Displays_Sign_%27We%27re_All_In_This_Together%22_New_York_City_COVID19.jpg).

Apple (2020), ‘The whole working-from-home thing’, Apple at Work, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6_pru8U2RmM, accessed 27 March 2023

Belot, M., S. Choi, E. Tripodi, E. Broek-Altenburg, J. C. Jameson and N. W. Papageorge, (2021), ‘Unequal consequences of Covid 19: Representative evidence from six countries’, Review of Economics of the Household, 19(3): 769–83

BPS Communications (2022), ‘BPS launches new campaign to make social class a protected characteristic’, available at: https://www.bps.org.uk/news/bps-launches-new-campaign-make-social-class-protected-characteristic, accessed 25 April 2023

Burgess, R. (2020), ‘COVID-19 mental-health responses neglect social realities’, available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01313-9, accessed 25 March 2023

Burns, J. (2015), ‘Poverty, inequality and a political economy of mental health’, Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 24: 107–13

Carr, D. (2022), ‘Opinion | Mental health is political’, The New York Times, 20 September 2022, available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/20/opinion/us-mental-health-politics.html, accessed 23 March 2023

Chatzidakis, A. and J. Littler (2022), ‘An anatomy of carewashing: Corporate branding and the commodification of care during Covid-19’, International Journal of Cultural Studies, 25(3–4): 268–86

Citraningyas, T. (2020), ‘Changing face of mental health’, Inside Indonesia, available at: https://www.insideindonesia.org/changing-face-of-mental-health, accessed 23 March 2023

Fenwick, R. and M. Tausig (2007), Work and the political economy of stress: Recontextualizing the study of mental health/illness in sociology, in W. Avison, J. McLeod and B. Pescosolido (eds), Mental Health, Social Mirror. New York: Springer, pp. 143–67.

Centre for Mental Health (2020), Inequalities in Mental Health: The Facts, London: Centre for Mental Health

Henderson, C., G. Thornicroft and G. Glover (1998), ‘lnequalities in mental health’, British Journal of Pschiatry, 173: 105–09

Honkonen, T., M. Virtanen, K. Ahola, M. Kivimäki, S. Pirkola, E. Isometsä, A. Aromaa and J. Lönnqvist (2007), ‘Employment status, mental disorders and service use in the working age population’, Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 33(1): 29–36

Indra, R. (2021), ‘As COVID-19 worsens, govt, public figures launch social media campaign’, The Jakarta Post, 16 July 2021, available at: https://www.thejakartapost.com/life/2021/07/16/as-covid-19-worsens-govt-public-figures-launch-social-media-campaign.html, accessed 23 March 2023

Marshall, L., J. Bibby and I. Abbs (2020), ‘Emerging evidence on COVID-19’s impact on mental health and health inequalities’, The Health Foundation, available at: https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/blogs/emerging-evidence-on-covid-19s-impact-on-mental-health-and-health, accessed 25 March 2023

McGonagle, E. (2020) ‘Dettol’s back to work campaign goes viral for all the wrong reasons’, PR Week, available at: https://www.prweek.com/article/1693513?utm_source=website&utm_medium=social, accessed 26 March 2023

Moncrieff, J. (2022), ‘The political economy of the mental health system: A marxist analysis’, Frontiers in Sociology, 6: 1–11

Mumbrella (2021), ‘Twitter reveals most popular pandemic related hashtags’, available at https://mumbrella.com.au/twitter-reveals-most-popular-pandemic-related-hashtags-701982, accessed 27 March 2023

Pierce, M., S. McManus, H. Hope, M. Hotopf, T. Ford, S. Hatch, A. John, E. Kontopantelis, R. Webb, S. Wessely and K. Abel (2021), ‘Mental health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent class trajectory analysis using longitudinal UK data’. Lancet Psychiatry, 8: 610–19

Sobande, F. (2023), Consuming Crisis: Commodifying Care and COVID-19, Cardiff: Cardiff University

Starr, R. L., C. Go and V. Pak, (2022), ‘“Keep calm, stay safe, and drink bubble tea”: Commodifying the crisis of Covid-19 in Singapore advertising’, Language in Society, 51(2): 333–59

Traveloka (n.d.), ‘Smart traveling hacks for smart traveller by Traveloka’, available at https://www.traveloka.com/en-id/hotel-guides/smart-traveler, accessed 27 March 2023

Wang, H., X. Yang, T. Yang, R. Cottrell, L. Yu, X. Feng and S. Jiang (2015), ‘Socioeconomic inequalities and mental stress in individual and regional level: A twenty one cities study in China’, International Journal for Equity in Health, 14(25)

Wahlquist, C. (2022), ‘“Maybe I should just stop and enjoy my life”: how the pandemic is making us rethink work’, The Guardian, 15 January 2022, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2022/jan/15/maybe-i-should-just-stop-and-enjoy-my-life-how-the-pandemic-is-making-us-rethink-work, accessed 26 March 2023

Weich, S. and G. Lewis (1998), ‘Poverty, unemployment, and common mental disorders: Population based cohort study’, British Medical Journal, 317: 115–19

To cite this paper please use the following details: Larasati et al. (2023), 'Mental Health: Is Pandemic Stress Exclusive to the Rich?', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 16, Issue 2, https://reinventionjournal.org/article/view/1394. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.