Kleopatra Efstathiou, University of Warwick

Griffin Rohleder, Monash University, Australia

I sit at home watching TV; the daily COVID numbers are being announced. Mask wearers are praised; ‘covidiots’ are shamed. My mother rushes past to a smoking oven containing her baking sourdough. She has been looking after us all day but will miss tonight’s dinner as she attempts to meet her deadlines before tomorrow morning’s ‘Zoom’ meeting.

In Australia and the United Kingdom, government-mandated pandemic responses, such as lockdowns, were more than a simple case of ‘working from home’. Throughout the pandemic, our identities were socially constructed, reconstructed and governed according to emergent normative hierarchies. Our individual decisions to wear masks and work from home certainly mattered, but they were influenced and characterised by how the pandemic was spoken about.

Narratives provide ‘a clear sequential order that connects events in a meaningful way for a definite audience’ (Hinchman and Hinchman, 1997: xvi). While ‘saving lives’ is usually associated with doctors and nurses, firefighters and the police, during the pandemic we were suddenly told that we all could do our bit to save lives. For many, this was galvanising. Over time (and at varying paces), however, this effort to save lives was reframed as a responsibility: a requirement, even.

We draw on Narrative Policy Framework (NPF), as defined by Mintrom et al. (2021), to explore how COVID-19, as a policy setting, inspired the creation of characters (heroes, villains and victims), a plot and a policy moral through which the populations of Australia and the United Kingdom – similar anglophone countries with largely neoliberal states – attempted to make sense of the crisis, and whose remit spanned the whole of society. We focus on three identities that interacted with COVID policymaking: the ‘dutiful citizen’, ‘supermum’ and the ‘unvaccinated’, seeking to demonstrate that normative hierarchies could be supported or challenged in meaningful ways: that these narratives, as they were, mattered.

The fact that anyone could catch and pass on the virus provided a natural foundation for the ‘responsibilitisation’ of the individual, as the everyday act of breathing became a subject of social and political scrutiny (Davies and Savulescu, 2022). Moreover, as one medical ethics paper muses, ‘times of crisis mandate an “all hands on deck” response’ (Redmann et al., 2020: 325). These two features of the COVID policy setting may suggest why war-like rhetoric became a favoured tool of policy communication in our cases: it conveys immediacy and situates responsibility at the individual level by demanding personal sacrifice.

In a speech launching Australia’s 1942 war loan drive, Prime Minister John Curtin announced ‘the complete mobilisation […] of all the resources, human and material, in this Commonwealth […] that every human being in this country is now, whether he or she likes it, at the service of the Government to work in the defence of Australia’ (British Pathé, 2014). By comparison, when announcing AUD $1.1 billion to support mental health and domestic violence services during the pandemic, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison suggested, ‘we battle coronavirus on both the health and economic fronts’ (Morrison, 2020a). Days later, Morrison would reiterate this framing on a popular evening news programme, speaking of a ‘war on two fronts. We’re fighting the virus, and we’re fighting the very serious economic impacts of that virus’, identifying the need to ‘keep our distance, to ensure that we’re following the rules’ and to ‘keep doing the right thing’ to ensure ‘we have the best chance of saving lives and saving livelihoods’ (Morrison, 2020b).

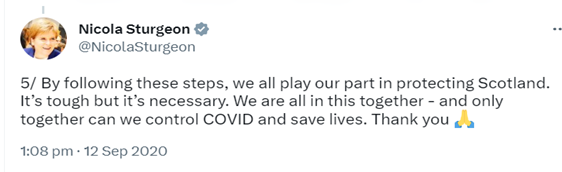

Similarly, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson described the pandemic as a ‘fight [in which] each and every one of us is directly enlisted’ (Johnson, 2020). In a study conducted by Mintrom et al. (2021) analysing 26 of Johnson’s speeches, war-like terminology was used in 22, individual citizens were identified as the hero in all 26, while the policy moral of the war ‘being winnable by citizens’ appeared in 23 (Mintrom et al., 2021: 1226). In a similar fashion, Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon tweeted, ‘we all play our part in protecting Scotland. It’s tough but it’s necessary’ (Sturgeon, 2020).

Responding to the COVID-19 policy setting in this way was not a given; it was a choice: German Chancellor Angela Merkel, for instance, would frequently describe the setting in neutral terms such as ‘crisis’ or ‘situation’ (Mintrom et al. 2021: 1225). Although it is not the only character identifiable in the above discourse, the conflation of the citizen with the soldier carries with it certain expectations and responsibilities. For some, it may stoke pride or camaraderie; for the government, it provides an external attribution of responsibility (and blame) should things go wrong. If, as Sturgeon (2020) says, ‘only together can we control COVID and save lives’, then those who are compliant and choose to observe protocol may be lauded as ‘heroes’, while those who do not are imputed ‘villains’, derelict in the duties and caring little for the harms they may inflict on victims qua the at-risk population.

COVID identities were not constituted ex nihilo: they formed out of interactions between the policy setting, narrative and existing social arrangements. If war demands civilian sacrifice, then a greater demand on the working mother – the need to ‘hold it all together’ (Herten-Crabb and Wenham, 2022: 1229), as one study participant described it, or transform into a ‘superhero’ in the words of another (Herten-Crabb and Wenham, 2022: 1226) – is to be expected.

Specifically, many UK women found themselves constantly balancing household tasks with minding the children and helping with schoolwork (Adisa et al., 2021: Herten-Crabb and Wenham, 2022). The ‘supermum’ can thus be thought of as an extension of the ‘double burden’ of work and care described in feminist literature (Hochschild, 1989), jointly caused by it and COVID lockdowns. Consequently, the conflation of personal and professional life stemming from confinement to the home altered the professional-household labour balance for many women (Adisa et al., 2021). To wit, the diametric ‘pull’ of different identities: the dedicated, efficient worker and the – traditionally feminine – provider of oft-unpredictable care in the home qua gendered space came to the fore for many (Adisa et al., 2021). However, are they heroes of a lockdown regime, or are they victims of an institutionally exacerbated second shift?

A policy moral emphasising individual accountability gave rise to one of the most stigmatising and prolific ‘new’ identities of the COVID era: ‘vaccination status’. In Australia, perhaps the greatest narrative significance was found in Victoria, where sporadic, state-wide lockdowns did not end until late September 2021, with the achievement of a ‘70 percent double dose’ vaccine uptake (Premier of Victoria, 2021). So emphatic was the vaccination campaign that the Victorian government spoke at this time of a ‘vaccinated economy’, a future in which ‘Victorians who choose not to get vaccinated will be left behind’ – in spite of the substantial memetic phenomenon of ‘togetherness’ which featured elsewhere in pandemic communication – as entertainment and hospitality venues reopen, but only to those fully (two dose) vaccinated (Premier of Victoria, 2021). A similar schema was seen in the UK, where moving to ‘Plan B’ in 2021 made the display of the NHS Covid Pass mandatory to enter crowded spaces, including both indoor and outdoor settings and nightclubs, which included either full vaccination or negative testing (UK Government, 2021b).

Although well-intentioned, the simplistic, binary, and very public nature of vaccination status would see its politicisation seep easily into many facets of life. Mandatory vaccinations in the workplace would force the unvaccinated to choose between their beliefs and their previously assumed rights and livelihoods (Bardosh et al., 2022), potentially appearing as ‘villains by inaction’, failing to ‘do their part’ and contribute to the war against COVID on the economic front. Alternatively, those who could not get vaccinated may have felt the need to ensure those around them knew why, to avoid being associated with ‘villainous’ ‘out-group’ milieus known for spreading ‘tin pot theories’ (ABC, 2021a: Berger, 2018: 57), and engaging in violent protest (ABC, 2021b).

In reference to an anti-vaxxer who accosted nurses in a Melbourne vaccination clinic, then-Victorian Health Minister Martin Foley spoke of keeping ‘the thousands of Victorians who want to do the right thing safe from harassment’ (ABC, 2021a). The popular definition of ‘right’ behaviour, and the situation of the onus for it at one level or another, is not given; it is constructed within the bounds of popular discourse. Certainly, then, narrative construction has meaningful implications for the person on the street, in the office, the schoolyard or the home, as even the everyday person is affected by the framing effect of policy narrative construction.

For the academy, this should highlight the importance of sound qualitative analysis when considering whole-of-society issues. To what extent might the pandemic norm of the ‘supermum’ entrench itself? Will vaccination status continue to characterise social relations in a meaningful way? How might the choice to engage in war-like communication styles and the association of the unvaccinated status with an ‘anti-vax’ identity have affected – and continue to affect – vaccine uptake or social polarisation? Might the ‘unvaccinated’ feel pushed towards more extreme ideologies as they are ‘out-grouped’ by mainstream society? A quantitative study of foregone incomes, hours worked, death or vaccination rates would not, alone, tell a complete story here.

Figure 1: UK Government slogan. ‘Stay at Home. Protect the NHS. Save Lives.’ UK Government slogan (UK Government, 2021a).

Figure 2: ‘We are all in this together – and only together can we control COVID and save lives.’ (Sturgeon, 2020). Published 12/09/2020. https://twitter.com/nicolasturgeon/status/1304723431309672453

ABC. (2021a), ‘No new COVID-19 cases in Victoria as authorities boost security after anti-vaccination protest’. Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2 July 2021, available at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-07-02/victoria-covid-cases-daniel-andrews-national-cabinet-vaccine/100261676 accessed 06 April 2023.

ABC. (2021b), ‘Police label protesters “cowards” as 62 arrested after crowd storms through Melbourne’s CBD’. Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 21 September 2021, available at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-09-21/victoria-construction-industry-shutdown-melbourne-protest-police/100478450 accessed 06 April 2023.

Adisa, T. A., O. Aiyenitaju, and O. D. Adekoya (2021), ‘The work–family balance of British working women during the COVID-19 pandemic’. Journal of Work-Applied Management 13: 241–60, available at https://doi.org/10.1108/JWAM-07-2020-0036 accessed 06 April 2023.

Bardosh, K., A. De Figueiredo, R. Gur-Arie, E. Jamrozik, J. Doidge, T. Lemmens, S. Keshavjee, J. E. Graham, S. and Baral (2022), ‘The unintended consequences of COVID-19 vaccine policy: Why mandates, passports and restrictions may cause more harm than good’. BMJ Global Health 7: 1–14, available at https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2022-008684 accessed 06 April 2023.

Berger, J. M. (2018), Extremism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

British Pathé. (2014), ‘Australia’s Prime Minister speaks (1942)’ [Video]. YouTube. 13/04/2014, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WWeiGllzVDQ accessed 06 April 2023.

Davies, B. and J. Savulescu (2022), ‘Institutional responsibility is prior to individual responsibility in a pandemic’. The Journal of Value Inquiry, available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10790-021-09876-0 accessed 06 April 2023.

Herten-Crabb A. and C. Wenham (2022), ‘“I was facilitating everybody else’s life. And mine had just ground to a halt”: The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on women in the United Kingdom’. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society 29(4): 1213–35, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxac006 accessed 06 April 2023.

Hinchman, L. P., and S. Hinchman (1997), Memory, Identity, Community: The Idea of Narrative in the Human Sciences. New York: SUNY Press.

Hochschild, A. R. (1989), The Second Shift: Working Parents and the Revolution at Home, NY: Viking Penguin.

Johnson, B. ‘Prime Minister’s statement on coronavirus (COVID-19): 23 March 2020’. Published 23 March 2020, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-address-to-the-nation-on-coronavirus-23-march-2020 accessed 02/10/2023.

Mintrom, M., M. R. Rublee, M. Bonotti and S. T. Zech (2021), ‘Policy narratives, localisation, and public justification: responses to COVID-19’. Journal of European Public Policy 28(8): 1219–37, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1942154 accessed 06 April 2023.

Morrison, S. (2020a), ‘$1.1 billion to support more mental health, Medicare and domestic violence services’. Published 29 March 2020, available at https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-42763 accessed 02/10/2023.

Morrison, S. (2020b), ‘Interview with Tracy Grimshaw, A current affair – Channel 9’. Published 02 April 2020, available at https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-42771 Accessed 02 October 2023.

Premier of Victoria. (2021), ‘Victoria’s roadmap: delivering the national plan’. Published 19 September 2021, available at https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/victorias-roadmap-delivering-national-plan accessed 06 April 2023.

Redmann, A. J., A. Manning, A. Kennedy, J. H. Greinwald and A. de Alarcon (2020), ‘How strong is the duty to treat in a pandemic? Ethics in practice: point-counterpoint’. Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery 163(2): 325–27. American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820930246 accessed 06 April 2023.

UK Government. (2021a), ‘New TV advert urges public to stay at home to protect the NHS and save lives’. Published 10 January 2021, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-tv-advert-urges-public-to-stay-at-home-to-protect-the-nhs-and-save-lives accessed 07/04/2023.

UK Government. (2021b), ‘Prime Minister confirms move to Plan B in England’ [Press Release]. Published 08 December 2021, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-confirms-move-to-plan-b-in-england Accessed 21/09/2023.

To cite this paper please use the following details: Efstathiou et al. (2023), 'Identity: Narratives of Heroes, Villains and Victims', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 16, Issue 2, https://reinventionjournal.org/article/view/1387. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.