Xinting Du, University of Warwick, University of Cambridge

This article identifies an under-explored connection between queerness and cinematic food, especially focusing on food images in Chinese queer cinema. Queer theories, food studies and philosophy of food are brought together in a discussion of a cinematic text: The River (1997). The discussion explores two questions: (1) Do these food scenes convey different symbols in comparison to Western queer cinema? (2) How do these food images register Chinese family relations and queer kinship? By examining how food is portrayed in this film, this article considers the notion of ‘depraved food’ and further suggests that on-screen food images can be read as a stand-in for Chinese queerness. Consequently, it is proposed that these food images critically depict Taiwan during the 1990s, especially how the traditional Confucian family and Confucian values are challenged by the modern crisis, conversely, the innovative Chinese queer family appears.

Keywords: Chinese queer cinema; food images; Tsai Ming-liang; 1990s; Confucianism; queer family; The River; Food images in Tsai Ming-Liang’s The River’; Taiwan society in 1990s.

Chinese identity is significantly shaped by Confucianism, with a focus on the discrete unit of the Confucian family as well as on the broader nation. As Li Minghui writes, ‘the idea of family is a central one for the Confucian project’ (Lee, 2017: 7). Such a family-based national ideology characterises a Chinese Confucian family as a hierarchical unit built on patriarchy and filial duty. Specifically, it maintains the order of the whole nation, representing the privileged normality. Yet, the position of Confucianism in modern society faces a series of challenges and crises: the threat from modernisation, globalisation and Western capitalism, and the decline of the Confucian family structure to name but a few (Li, 2017: 1). In this context, due to its subversion of sex and gender norms, queerness must be an anathema to the formation of a Confucian family.

This article considers the above concerns by exploring the relationship between food elements, the formation of Chinese families, and the emerging queer characters in Chinese contemporary cinema. The actions of cooking and eating typically involve processes of physical and physiological destruction and violence: people cut, chop and cook ingredients before they chew and digest the food. In this article, the focus is on the Taiwanese queer film The River (Tsai, 1997), particularly looking at the food practices of queer characters, which represent their homosexual desire and queer subjectivity, as an entry point. The destructive process is embodied in changes to more quotidian elements: here, the significance of food and its related behaviours – how food is prepared, cooked and eaten. As such, the maxim ‘you are what you eat’ is much more than pure sustenance.

The basic information and principles of Chinese food culture are fundamental to the reading of The River (Tsai, 1997) as a cinematic text. This article is evoked by Korsmeyer’s question of whether the taste of the food is imbued with flavour or if it also carries moral valence (Korsmeyer, 2012: 89). She explains that:

Even ordinary, everyday acts of cooking and eating are forms of ethical conduct. Cultural and religious traditions since antiquity have prescribed what we should and should not eat. In fact, ethical choices about food used to be considered as important as other more recognizably moral issues. (Kaplan, 2012: 8) As a sub-category, table manners refer to ‘appropriate eating and drinking behaviors’. These rules are a series of regulations that encompass all activities related to food, including but now limited to how the table is arranged, what utensils are used and when, and where one places their hands and feet when eating. (Kaplan, 2012: 9)

Table manners and moral aspects of food can be integrated into the reading of the ordinariness of the Chinese queer family. The following cinematic analysis of The River will particularly focus on the subversive representation of food elements in terms of table manners to further explore how these queer foods challenge the entrenched Confucian family.

The River tells a story of a young Taiwanese man, Hsiao-Kang (Kang-sheng Lee). He and his parents are like strangers, even though they live in the same small flat in Taipei. Hsiao-Kang’s father (Tien Miao) regularly has sex with young gay men in gay saunas. His mother (Yi-Ching Lu) works in a restaurant and often bringing leftovers home. She is having affair with a pornographer.

Hsiao-Kang’s story begins with his experience as a stand-in movie actor, playing a floating corpse in the polluted Tamsui River. Hsiao-Kang subsequently develops chronic neck pain that proves incurable, despite trying many treatments. Eventually, Hsiao-Kang’s father decides to take him to look for a local healer. That night, Hsiao-Kang encounters his father in a dark room in a gay sauna and they mistakenly have sex with each other.

As Tiago De Luca suggests, Tsai Ming-liang’s The River is characterised by its focus on the animal-like human body and how it exists in domestic spaces. Significantly, the film ‘opened the doors of domestic privacy’ that were previously closed off to mainstream cinema’s attention (De Luca, 2011: 158). Tsai’s attention to excessively private, everyday issues contains many easily overlooked food images, such as boxed lunches from the film set, packed drinks, leftovers and fruit. At the same time, he introduces both private (Hsiao-Kang’s home and car, and hotel) and public places (a breakfast stall, film sets, and a McDonald’s restaurant) related to food. Rey Chow suggests the quality of “excess” in the film, specifically referring to the excess of metaphorical meaning presented on-screen (Chow, 2004: 133).

To expand the concept of ‘excess’ into the realm of food images, it can be argued that food images also convey the allegorical nature of The River. While it is not a typical example of the ‘food film’ genre, the movie contains numerous subtle food images within its complex and rich cinematic text. It is suggested that The River’s food images have been largely ignored, even though there are strong non-verbal expressions belonging to what Chow describes as ‘the most quiet yet radical manner’ (Chow, 2004: 138). Even so, these food images reveal the themes of isolation and alienation that have been mentioned in much scholarly literature and become what I define as ‘depraved food’.

My definition of ‘depraved food’ is based on the Confucian concept of lun and the related principles of food ethics. Since food ethics describe foods using qualities typically ascribed to humans and human behaviour such as ‘wicked’, ‘brave’ and ‘honest’, I shall describe the food images in The River as ‘depraved’ (Korsmeyer, 2012: 94). This adjective is applied to describe food (and its related scenes) that subvert/challenge/queer the conventional principles of Chinese food culture and broader family values. What is behind these conventional regulations/standards is Confucianism, which is accepted as the most dominant cultural force and religion in China (Sun, 2013: 2). As a significant Confucian value, lun (伦) refers to five principal relationships, which not only include the blood relations (such as father and son, husband and wife), but also broader culture and social relations (such as old and young, emperor and official) (Park and Chesla, 2007: 303). To phrase this another way, lun emphasises the ubiquitous regulation and hierarchy that is present in all aspects of Chinese society, even in terms of table manners. Thus, the literal meaning of the term incest (i.e., 乱伦 luanlun, which can be translated as a subversion of the ‘lun’) refers to ‘the overturning of kin or, more precisely, of hierarchically arranged social relations’ (Chow, 2004: 136).

Similarly, these ‘depraved’ food transgresses the hierarchically arranged table manners and their association with the power structures of the Chinese Confucian family. The argument put forward below will be further clarified with a detailed analysis of the food images/scenes shown in the film, including the representation of depraved food related to the father, mother and son. Following that, it will explore how the depraved food images reflect the reconstruction of the Confucian family in 1990s Taiwan.

There are few depictions of formal Chinese family meals in The River, although the film is filled with informal food such as fast food, leftovers and fruit. Mary Douglas states that food habits encode the social background (Douglas, 2002: 249). In contrast to Western food culture, Chinese food culture has structural and performative features (Cooper, 1986: 179). Hsu describes the basic structure of Chinese dining as follows:

The typical Chinese dining table is round or square, the ts’ai (菜, dishes) dishes are laid in the center, and each participant in the meal is equipped with a bowl of fan (饭, rice/grain), a pair of chopsticks, a saucer, and a spoon. All at the table take from the ts’ai dishes as they proceed with the meal. (Hsu, 1977: 304)

Hsu’s depiction introduces conventional table manners, which include the structure, equipment and setting of a Chinese formal meal. Such table manners reflect the concept of lun: for example, a Chinese meal has an inner hierarchy, wherein fan (rice) forms the base, and vegetables, fruit and meat constitute expendable dietary elements (Chang, 1977). Similarly, the table manners are reflective of the inner hierarchy of the Chinese family: the child needs to obey and demonstrate deference, while the father/husband sits at the head of the table surrounded by his family, thus underscoring his indubitable position of power.

Based on such structure, it is fair to say that Tsai subverts this structure through the use of depraved food. A key example is the recurring images of Hsiao-Kang’s father eating alone at a small table. The first scene takes place during the day when the father is sitting at a small table and eating food. Although this scene is set in the home – a private/domestic place – the absence of his family conveys a sense of imbalance in this visual composition. He warms up the leftovers for himself with a rice cooker, a commonly used Chinese cooking utensil typically used to cook rice rather than formal dishes.

In addition to the abnormal dining situation, the cinematic design creates a sense of unease in the food scene (Figure 1): the composition of the scene constrains the subject as if confined in the frame, thus conveying a sense of depression, as opposed to relaxation. Meanwhile, the medium shot does not provide a precise depiction of the food, instead dissolving the food into the surrounding environment, which attends to basic physical needs (like the minimalist furniture in the scene). It is hard to describe the food’s taste and because the cinematic text offers no clue about it; homely food is portrayed as a physiological imperative (Chow, 2004: 130) rather than sources of warmth or pleasure. Furthermore, the soundtrack to the food scene includes uncomfortable noises, such as the piercing sound of utensils rubbing directly against each other, mechanical chewing and food landing on the table. These subtle noises, as Song Hwee Lim suggests, serve to amplify the silence (Lim, 2014: 119), reinforcing the themes of isolation and alienation.

Fran Martin describes such silence as ‘an uncomfortable emptiness’ (Martin, 2003: 177). It is suggested here that this is most likely attributable to how these noises subvert the expectation of homely food, which is typically characterised as warm, cosy and relaxed. Such settings are usually places in which individuals can be fully engaged due to the conventional cinematic emphasis on food’s temptations and intimacy. However, in terms of audio-visual design, the depraved food in The River is repressed. This scene helps to establish the father figure as an explicit clue to ‘the dissolution of the kinship system based on seniority and hierarchy’ (namely, the subversion of lun: incest). The depraved food suggests his loss of patriarchal control over the entire family unit (Chow, 2004: 135).

The second scene is highly similar to the first one: Hsiao-Kang’s father is eating another meal at the same dining table. In this instance, it is only the darkness of the background that suggests the passage of time, thus allowing the viewers to determine that the two scenes are not the same (Figure 2). Additionally, the loose shot scale allows the audience to see more space within this apartment: the bathroom to the side and the bedroom to the rear. Taken together, the interior settings such as doors and walls fragment the domestic space. Such a cinematic strategy presents the different events happening within this space simultaneously yet in isolation from each other. De Luca comments on such sectional space, suggesting that it can present how these characters engage in their own activities in ‘different planes across and within the frame’ (De Luca, 2011: 160). When the father is eating, Hsiao-Kang leaves the bathroom and goes back to his room. The two physiologically opposing activities (eating and elimination) happen simultaneously to reduce the edible property of food. In contrast to the conventional expectations of a homely food scene, this scene further emphasises the isolation within the family and challenges the traditional Chinese arrangements.

Figure 1: Hsiao-Kang’s father enjoying a lonely meal

Figure 2: Hsiao-Kang’s father enjoying a lonely meal in the night

Poor table manners also appear at the same table when Hsiao-Kang uses a serving spoon to eat rice directly from the cooker (Figure 3). Although Chinese food culture involves individuals sharing dishes between themselves, rice is the exception to this; it is normally served in people’s own bowls, signifying personal space and etiquette. In a Chinese family’s daily life, if rice is not served properly from the rice cooker, it will be regarded as poor manners – what Cooper describes as ‘disinterest, disrespect and carelessness’ (Cooper, 1986: 180). Therefore, Hsiao-Kang’s eating behaviour overturns the cultural norms relating to table manners. The mise-en-scène continues with the scenes of the father eating dinner alone, with the food shown to be unappetising. The dim lighting further depicts food as a basic physical need rather than any social or leisure event. Additionally, Hsiao-Kang’s naked body and strange behaviour seem to suggest he is more animal than human highlighted further by the degradation of his table manners. David Kaplan suggests that food virtue is crucial to ensuring human dignity; nevertheless, this scene presents food as depressing because its rich ethical value is infinitely wrung out, leading it to become ‘depraved food’ (Kaplan, 2012: 9).

From a narrative perspective, Hsiao-Kang’s behaviour is caused by his neck pain: his physical disability makes him incapable of maintaining and cooking a normal meal (as mentioned, a normal Chinese meal is consists of rice and dishes). Crucially, his neck pain also stops him from conforming to the expected content and manner of traditional Chinese dining etiquette. The representation of depraved food portrays what Chow describes as ‘destitution and deviance’, characteristics of the psychologically and morally defective contemporary urban human (Chow, 2004: 133).

It is suggested that the morally anarchic concept is expanded into the field of food. If the father’s depraved food – eating along – implies the disintegration of the traditional Confucian family, Hsiao-Kang’s depraved food suggests a youth’s disability or inability to act brought about by contemporary social change and crisis in Taiwan. As Kuang-Tien Yao points out, the globalisation of Taiwan creates an ‘emptiness and hopelessness’ for those people who are marginalised in society. The young generation, such as Hsiao-Kang, is not fully prepared to take part in these new urban activities and the ongoing economic boom (Yao, 2005: 231, 238). Instead, they wander around the city, eating like a lonely animal.

Figure 3: Hsiao-Kang’s strange and animal-like table manner

Hsiao-Kang’s mother, the female character, seems to play a rather limited role in the film. Of the few scenes in which she appears, most are outside the domestic space (home), such as the restaurant where she works, her lover’s car and her lover’s home. The absence of any representation of domestic females reflects Tsai’s cinematic response to Taiwan’s shifting social landscape during the 1990s. New job opportunities emerged when economic growth began in the 1970s, thus leading Taiwanese women to undertake gainful employment outside of the home. By the 1990s, it was usual for women to enter the labour market, with some of them accessing better employment opportunities after having received a proper education (Yao, 2005: 231).

Hsiao-Kang’s mother is portrayed as a female character relegated to a low-skilled job who rarely appears in the home. She rejects the conventional duties of a mother and wife in a Confusion family and does not cook for or feed her family. The depraved food brought by Hsiao-Kang’s mother is mostly embodied by leftovers, what remains of commercial food sold in a restaurant. In her first scene, she is depicted as a sociable, independent person: the long shot frames her in the centre, standing and eating leftovers from the restaurant (Figure 4). As the following plot will reveal her love affair, therefore, this depraved food symbolises her detachment from both familial responsibilities and traditional food ethics. The place where she eats is temporary and constructed from some boxes. Unlike the cosy and stable domestic space, the temporary nature and instability of where she chooses to eat are reflective of the transient and unstable nature of her love affair. Besides, the depiction of Hsiao-Kang’s mother’s experience working in a commercial public location suggests that she is the only person in the family who has integrated into the increasingly commercialised and globalised Taiwan. This is emphasised later when she gets into her lover’s car and feeds him with her hands (Figure 5).

Some scholars have explored food as a symbol of sexual queer desire in queer cinema, such as the peach in Call Me By Your Name (2017) and the hive/honey in Fried Green Tomatoes (1991). These viscous, sweet and natural foods represent the queer characters’ sexual desire. Nevertheless, as a queer film, The River utilises food images to suggest heterosexual desire instead (Tandoh, 2018). It is posited that the only detailed representation of heterosexual relationships within the whole film is still framed within an incestuous (乱伦, luanlun) context. This directly challenges lun, a crucial Confucian value that is embodied by a ‘moral emphasis on seniority, order, and propriety’. Specifically, lun is a criterion that all Chinese individuals should obey (Chow, 2004: 135).

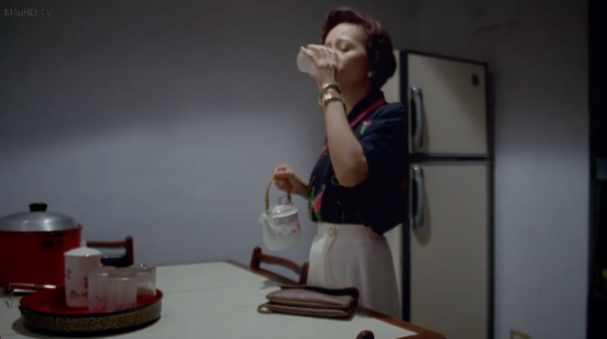

Here, the depraved food linked to the mother figure suggests the sexual intimacy between the wife/mother and another man, these scenes challenge the structure of the Confucian family. Either standing or eating with one’s hands represent alternative forms of table manners, which minimise the traditional moral properties of the food. In this extramarital affair, she feeds her lover with food, while he feeds her longing for heterosexual love. The representation of depraved food confers upon her agency as a modern woman. This idea is explored in her following scenes in a domestic setting, where she never eats in the home, instead endlessly drinking water (Figures 6 and 7).

Corrado Neri offers a useful metaphor; he writes that ‘the disappearance of emotion, something that, like water in a drought, is nowhere to be found’ (Neri, 2008: 400). Chow also mentions that ‘water has always been a potent symbol of the sexual unconscious and (desire for) lover’ in Tsai’s films (Neri, 2008: 395). Thus, the repetitive scenes where the mother drinks water illustrate her unquenchable thirst (physical sustenance, love and desire), and her desire to be watered like a parched plant. It further suggests her eagerness to receive the heterosexual love and desire that can never be satisfied by her husband. The traditional Confucian wife is often tied to familial duty and obligation, however, Hsiao-Kang’s mother embarks on an affair out of pure desire. Consequently, the food images relating to her are symbols of incest, ‘anomie, estrangement, desperation, and general social malaise’ (Chow, 2004: 127). The depraved food images lack moral principles, suggesting her inability to fulfil the culturally appropriate gender role as a Confucian wife/mother figure.

Figure 4: Hsiao-Kang’s mother stands and eats the leftovers

Figure 5: Hsiao-Kang’s mother feeds her lover with her hands

Figure 6: Hsiao-Kang’s mother continually drinks water in domestic scenes (1)

Figure 7: Hsiao-Kang’s mother continually drinks water in domestic scenes (2)

As Yao suggests, the setting in Tsai’s film is a significant element because his characters barely talk to each other (Yao, 2005: 129). Therefore, the setting/place can be taken to always convey information and emotions. In addition to the lonely meals in the family home, Hsiao-Kang’s father also appears in a public food scene in McDonald’s, a Western-based multinational fast-food chain. This sequence conveys homosexual desire in a subtle and implicit way by presenting the McDonald’s restaurant as a public space in which gay men cruise for sex, as well as a space for consuming food. The Western setting challenges traditional Confucian values; homosexual love is anathema to the rigid gender system that is based on the binary of male (husband/father) and female (wife/mother) within the Confucian family (Chow, 2004: 136).

Confucianism regards the heterosexual family as the fundamental unit of society. Within the traditional gender binary, the father enters the public labour market, while the mother is responsible for bearing children and providing society with a young workforce. Through such compliance with Confucian moral principles, the economic production and consumption of a state and human society can function properly (Park and Chesla, 2007: 296). However, in the McDonald’s scene, the Western food chain subverts Confucian food ethics both in terms of food ethics and social dynamics. The transition from a dingy, small apartment to the bright, crowded McDonald’s is indicative of the shift from a Confucian homely place to a capitalist public place for food consumption. As Wu suggests, Taiwan, as a metropolis, reflects Western capitalist ideology in terms of food culture. To be precise, the fast-food chain deconstructs Confucian food culture, which is typically based on order and occurs in domestic spaces (Wu, 2002).

Figure 8: Hsiao-Kang’s father exchanges glances with the young gay man

The tonal information in this scene underscores such differences: the colour palette fits with the classic McDonald’s colourway of red and yellow, while the inclusion of light blue, another bright colour, evokes the desire to engage in public consumption. The transparent window creates a sense of exhibition of both the food and the consumers, ensuring that eye contact can be made between the display and viewers. In this way, Hsiao-Kang’s father is locked into a two-way gaze with the McDonald’s fast food in the window and the passers-by outside, respectively. Such a mode aligns with Gary Needham’s idea that ‘cruising is another way of looking’. Needham suggests gay male cruising is characterised as ‘the reciprocity of the glance and the often-playful exchange of looks’ (Needham, 2015: 49). Put simply, gay males typically initiate contact with other gay males by making first making eye contact.

This moment in The River establishes a parallel between the act of eating and the act of looking – both are forms of consumption. Through the transparent window, it can be seen that Hsiao-Kang’s father is positioned in the centre of the frame. When he is eating, his eyes search thoughtfully for something on the right of the window, as if he was examining and selecting merchandise that appeals to him. His wandering eyes also create a sense of expectation for what is on the other side of the glass. As his eyes shift, a young man appears from the right. Although the young man has his back turned to the viewer, the direction of Hsiao-Kang’s father’s eyes indicates that they make eye contact. Hsiao-Kang’s father stares at the young man while sipping his drink as if he was enjoying and tasting the young homoexual’s body (Figure 8). Food becomes a sensory device to evoke an association between appetite and sexual desire. The young man’s body is as ‘delicious’ and as readily accessible as the fast food served in the restaurant.

His appearance suggests the recognisability of his identity as a homosexual, what Bech (1997: 106) describes as ‘the welter of signs’, including his style of dress (black top with a large neckline and skinny jeans) and his furtive glances back. In comparison to the conventional male clothing in Chinese society, his appearance is slightly feminine, flamboyant, fashionable and revealing, indicating the objectification of his identity and how he positions himself as ‘being on display’. Henning Bech characterises the homosexual gaze as audacious for how it lingers in another temporal dimension, which allows the long and voluptuous stare (Bech, 1997: 106).

Such gaze is proposed that it is both an iconic gesture and an affective form of body language due to how gaze visually links the relationship between food and sex – especially the relationship between fast food and homosexual desire. John Ryle draws an analogy between food and sex, suggesting that the dynamic between two men is not a ‘dinner party’, but ‘fast food’ (Ryle, 1998). Elspeth Probyn also suggests the similarity between a public affair and fast food, in that both are ‘tainted by commercialization, and lack of taste or table manners’ (Probyn, 1999: 424).

Therefore, fast food becomes what this article refers to as ‘depraved food’ because it represents the deconstruction of Confucian values (especially food ethics) against the backdrop of growing commercialisation and globalisation in 1990’s Taiwan. The McDonald’s scene is the product of modernity and capitalist ideology as it produces large quantities of standardised food, such as hamburgers, fries and Coca-Cola, which people can eat using their hands, dispensing with the need for chopsticks and the absence of traditional Chinese table manners – and thus Confucian values. At the same time, it embraces the subversive gay culture as an anonymous commercial place for gay male cruising: gay males come here to both consume fast food and satiate their queer desire.

The next shot is a depiction of gay male cruising. A stationary shot is used to show how Hsiao-Kang’s father walks out of the McDonald’s and ‘chases’ the young man slowly down the corridor (Figure 9). Richard Tewksbury explores the concept of ‘the chase’, describing it as the process that takes place ‘between the initial eye contact and an eventual sexual contact… a series of interactions in which men pursue each other’ (Tewksbury, 1996: 15). This chase sequence contains frequent, intensive exchanges of glances. The place is shot as a symmetrical and seemingly endless corridor, which is darker than the bright artificial lights in the previous scene. The contrast between the unoccupied corridors and the colourful lights in McDonalds highlights the solitude and isolation of individual humans in an increasingly commercial society. Given this setting, the chase between the two men has shades of ironic warmth and intimacy. A similar vertical composition also appears in another scene – the sauna scene – in which Hsiao-Kang also seeks out a sexual partner, constructing a visual parallel between father and son. (Figure 10).

These two places can be read politically given the connection between McDonald’s and neocolonialism, and the sauna’s association with Japanese colonial rule over Taiwan (Marchetti, 2005: 117). The framing of these spaces creates what De Luca describes as an ‘explicit, indeed vertiginous, sense of depth’ as well as a sense of darkness and anonymity (De Luca, 2011: 164). Furthermore, as a ubiquitous food chain, McDonald’s represents the setting’s norms of anonymity where both food consumption and queer cruising can take place. With the decline of Confucian food norms, such anonymity facilitates subversive queer activities (Tewksbury, 1996: 9). In contrast, the darkness in the sauna helps to conceal the transgressive sexual activities that take place in a semi-public setting. As Bech argues, cruising, or the gaze, belongs to the city (Bech, 1997: 108). By depicting McDonald’s as a place for gay males to seek their sexual partners, food consumption turns into the consumption of homosexual desire and young male bodies. The similarity of the graphic composition of the McDonald’s corridor scene and sauna scene informs the understanding of the relationship between anonymous queer desire and locations for commercial food consumption. The seemingly infinite composition allows the characters to chase and get lost in their surroundings, in which the familiar domestic food space as well as the solidity of heterosexual mode are replaced and challenged by commercialisation.

Figure 9: McDonald’s corridor scene

Figure 10: The sauna scene’s similar composition as Figure 9

In conclusion, the above analysis highlights a myriad of depraved food images in The River. My analysis suggests these images are consciously designed to offer an alternative interpretation of Confucian values. Longji Song writes that the Chinese individual who is not defined by ethics becomes something inconceivable, the unethical subject (Sun, 1983: 30). Such an argument can be expanded into the field of food: it is proposed that those foodways that lack moral properties are depraved food, subverting the lun (伦, same as ethics in the English meaning), a fundamental Confucian cultural value. They are typically nondescript because the edible value is repressed and minimised.

By presenting images of depraved food, Tsai presents a critical depiction of Taiwan during the 1990s. To be precise, the conventional Confucian family has been reconstructed by capitalist ideology. The father, traditionally a figure of familial authority, eats alone without exercising control over his family. He eats in the fast-food chain and pursues another homosexual. Meanwhile, the mother is able to fit in with the commercialised society, bringing leftovers to her family, which makes her the literal ‘breadwinner’. At the same time, she abandons her conventional maternal duties, instead embracing the longing for extramarital heterosexual intimacy. Finally, the son eats alone, the transgression of Chinese table manners is reflective of a young, lonely soul grappling with the dysfunction of maintaining a conventional ‘normal’ life in a globalising society. Through depicting this depraved food, Tsai offers critical observations on 1990s Taiwan: a culturally hybrid society that oscillates between Confucian ethics and capitalist ideology. As Yao concludes, ‘it is portrayed mostly as an alienating, superficial, disjointed and impersonal modern globalized city’ (Yao, 2005: 219).

Figure 1: Hsiao-Kang’s father enjoying a lonely meal

Figure 2: Hsiao-Kang’s father enjoying a lonely meal in the night

Figure 3: Hsiao-Kang’s strange and animal-like table manner

Figure 4: Hsiao-Kang’s mother stands and eats the leftovers

Figure 5: Hsiao-Kang’s mother feeds her lover with her hands

Figure 6: Hsiao-Kang’s mother continually drinks water in domestic scenes (1)

Figure 7: Hsiao-Kang’s mother continually drinks water in domestic scenes (2)

Figure 8: Hsiao-Kang’s father exchanges glances with the young gay man

Figure 9: McDonald’s corridor scene

Tsai Ming-liang, (1997), The River [Film], Shiu Shun-ching, Taiwan

Bech, H. (1997), When Men Meet: Homosexuality and modernity, (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press)

Chang, K. C. (1977), Food in Chinese Culture, (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Cooper, E. (1986), ‘Chinese table manners: You are how you eat’, Human Organization, 45 (2), 179–84

De Luca, T. (2011), ‘Sensory everyday: Space, materiality and the body in the films of Tsai Ming-liang’, Journal of Chinese Cinemas, 5 (2), 157–79

Douglas, M. (2002) Implicit meanings: Selected essays in anthropology. Routledge.

Martin, D. F. (2003), ‘Vive L’Amour: Eloquent Emptiness’, in Berry, C. (ed) Chinese Film in Focus: 25 New Takes, London: BFI Publishing

Hsu, F. L. K. and V. Y. N. Hsu (1977), ‘Modem China: North’, in Chang, K. C. (ed.) Food in Chinese Culture, New Haven: Yale University Press

Kaplan, D. M. (ed.). (2012), The Philosophy of Food, vol. 39, (Berkeley: University of California Press)

Korsmeyer, C. (2012), ‘5. Ethical Gourmandism’, in Kaplan, D. M. The Philosophy of Food, (Berkeley: University of California Press), pp. 87–102

Lim, S. H. (2014), Tsai Ming-Liang and a Cinema of Slowness. (Hawai’i: University of Hawai’i Press)

Lee, M. H. (2017), Confucianism: Its roots and global significance. (Hawai’i: University of Hawai'i Press)

Marchetti, G. (2005), ‘On Tsai Mingliang’s The River’, in Berry, C. and Feii L. Island on the Edge: Taiwan new cinema and after, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press

Needham, G. (2015), ‘Cruising: Another way of looking’, Wuxia, (1-2), 44-67

Neri, C. (2008), ‘Tsai Ming-liang and the Lost Emotions of the Flesh’, Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique, 16 (2), 389–407

Park, M, and C. Chesla. (2007), ‘Revisiting Confucianism as a conceptual framework for Asian family study.’ Journal of Family Nursing, 13 (3), 293–311

Probyn, E. (1999), ‘An ethos with a bite: Queer appetites from sex to food’, Sexualities, 2 (4), 421–31

Ryle, J. (1998), ‘Outdoor Sex; the Junk Food of Love’, The Guardian, available at https://johnryle.com/?article=fast-food-gay-sex-and-the-tearoom-trade, accessed 16 September 2022

Sun, A. (2013), ‘Confucianism as a World Religion’, in Sun, A., Confucianism as a World Religion. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press

Sun, L. (1983), ‘Zhongguo Wenhuade’, ‘Shenceng Jiegou’, The Deep Structure of Chinese Culture. Hong Kong: Jixian Publishers.

Tandoh, R. (2022), ‘A Feast for the Eyes: Ruby Tandoh on food and film’, The Guardian, available at https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/mar/18/food-and-film-ruby-tandoh-call-me-by-your-name-moonlight-tampopo, accessed 16 September 2022

Tewksbury, R. (1996), ‘Cruising for sex in public places: The structure and language of men's hidden, erotic worlds’, Deviant Behavior, 17 (1), 1–19

Wu, I. F. (2002), ‘Flowing desire, floating souls: Modern cultural landscape in Tsai Ming-Liang's Taipei trilogy.’ CineAction, 58–64

Yao, K-T. (2005), ‘Commentary on the Marginalized Society: The Films of Tsai Ming-Liang’, in Kwok, R. Globalizing Taipei. Routledge, 219–40

To cite this paper please use the following details: Du, X. (2025), 'You Are What You Eat: Depraved Food and Chinese Queer Kinship in The River (1997)', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 18, Issue 1, https://reinventionjournal.org/index.php/reinvention/article/view/1373. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities, please let us know by emailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.

https://doi.org/10.31273/reinvention.v18i1.1373, ISSN 1755-7429 © 2025, contact reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk. Published by the Institute for Advanced Teaching and Learning, University of Warwick. This is an open access article under the CC-BY licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)