Benjamin R. Galbraith, University of Warwick

In a bid to explore the work of French sociologist Gustave Le Bon on dissimulating specific beliefs within a populace, this article will localise the factors he purported to amount to propagandistic success within the case studies of Nazi Germany and fascist Spain. This will be done using a consideration of primary visual sources and qualitative data associated with the campaigns in which they were used. Additionally, this work will analyse whether one can quantify propagandistic success, and whether this is at odds with the academic bases of Le Bon’s work. This research will ultimately provide a novel reading of Le Bon’s theory, demonstrating how the work can indeed allow for interesting analyses of different propagandistic contexts while concluding that there are limitations with the means through which the factors he brought to the fore directly contribute to successful propaganda initiatives.

Keywords: Gustave Le Bon and propaganda, theories of propaganda, public persuasion in case studies, Nazi propaganda analysed, fascist Spain propaganda analysed, factors amounting to propaganda success

Following the rapid development of mass-media technologies in the 1920s, propaganda has increasingly been harnessed by governments and non-state actors in order to influence individuals into acting in certain predefined ways. The best means to gain insights from this, however, remains yet to be seen, particularly due to a lack of scholarly consideration of this topic. Over the course of this work, propaganda will thus be defined as the following: ‘a deliberate and systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions, and direct behaviour to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the propagandist’ (Jowett and O’Donnell, 2019: 267). This terminology allows us to consider the specific intentions of propagandists while remaining conducive to the careful and critical analysis of early theories on propaganda.

This research will focus on the work of Gustave Le Bon, one of the earliest scholars of state-based persuasive messaging campaigns, and his seminal work, ‘Psychologie des foules’ [official English title translation: The Crowd], in which he explores in great detail the steps required for an effective state-based propaganda: l’affirmation, la répétition and la contagion (henceforth, affirmation, repetition and contagion)[1] (Le Bon, 1895: 55–56; 2007: 112–17). To best appraise Le Bon’s work within the context of more contemporary propagandistic campaigns, each tenet of Le Bon’s theory will be independently analysed to best understand how they interweave with greater societal trends. This will largely be facilitated by situating his work within the case studies of both fascist Spain (1936–1975) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). Given that Spain has been unfortunately side-lined within academic discourses of propaganda, following the thorough appraisal of Le Bon’s work, it will be independently considered to attempt to draw out unique insights. This paper concludes that while Le Bon’s work is certainly a useful tool in critically evaluating propagandistic trends, and that a broader interpretation of his theory of contagion helps navigate certain pitfalls in his work, his inability to clearly demonstrate factors to propagandistic success limit his work to that of a lens through which to perceive propaganda.

In the field of propaganda studies, the diversity of methodologies and approaches result in some discrepancy as to how one might best categorise the success of such works. When one considers the collection and interpretation of quantitative data, academics such as Marshall Soules and Jacques Ellul, two of the most prominent scholars on this topic, have argued that one must have a great deal of nuance when using public-opinion polls within an academic study as (i) they are liable to manipulation, and (ii) in totalitarian contexts, citizens (and governments) may modify submitted answers out of fear of the possible consequences (Ellul, 1965: 25; Soules, 2015: 64). The more recent generation of scholars, however, praise modern data analysis and collection techniques as a novel and precise means through which the effectiveness of propaganda and its success can be measured (Evans, 2007: 54; Kershaw, 1994: 144).

To best exemplify why this work will be assuming the perspectives of the former, we can turn towards the public opinion survey completed by the Office of Military Government, United States (OMGUS). This little-considered document outlines how, in 1949, in the US-administered zones of partitioned Germany, 66 per cent of inhabitants voiced support for ‘the idea of denazification’ (OMGUS, 1949: 305, original emphasis). While supporters of data collection would uncritically sing the praises of such research, it takes little to recognise that the conventionalisation of publicly expressed opinions often results in the vast underestimation in support for varying schemes (Margoli, 1984: 64). From this basis, it is particularly challenging to undertake judgements on the degree of support that German citizens – from an inadequately small sample size of the population – given the high likelihood of self-censorship upon answering this questionnaire, and during the Nazi regime. An entire research project could be undertaken on the methods for evaluating the success of a propagandistic campaign, but given the lack of space allocated to this paper, it is optimal for us to consider a successful propagandistic campaign to be one in which the desired goals and objectives of the propagandist (in this case, the state) are achieved. This will allow for considerations of the degree to which the propaganda, per Le Bon’s theory, was effective in influencing public attitudes, or whether other factors may need to be considered.

In turn, this work’s methodology will focus on perceiving the case study of Nazi Germany through the lens of Le Bon’s three main factors, and bring to light any academic inconsistencies that arise. Following these findings, Le Bon’s work will be used practically on the Spanish case study to draw out key ideas from a hitherto neglected context, while providing potential groundwork for future applications of this style. The primary visual sources included within this piece have been selected either due to their lack of inclusion within broader academic spheres, or their particularly cogent summation of propagandist themes across different contexts.[2] Undertaking this, alongside secondary sources, a succinct appraisal of Le Bon’s work within the age of early mass media will be able to be undertaken.

Let us firstly turn our attention towards Nazi Germany, and consider each of Le Bon’s factors within the broader remit of this context. Firstly, it bears mentioning that in Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler explains how, when attempting to counter certain ideas within a society, and consequently implant one’s own, one must have ‘definite spiritual convictions’ that are consistently applied across all of society, and that only once two ideas are pitted against one another, can force be used to triumph over the other (Hitler, 1924: 149).[3] This will form the basis of this subsequent analysis.

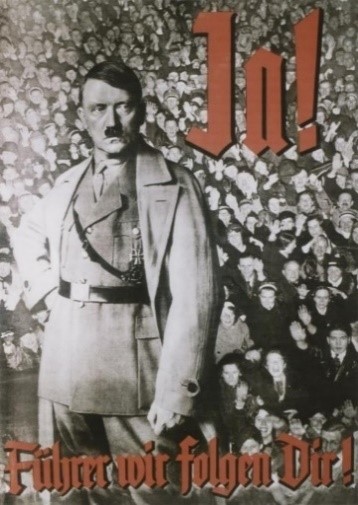

If we are to pick apart the thematic bases of these ‘definite spiritual convictions’, one can generally see the following: unity, ethnic superiority, a fundamental need to destroy the enemies of the nation, and the cult of leadership (Welch, 1987: 410). Given that Le Bon’s first stage in developing propaganda is predisposed upon messages being condensed into more digestible morsels of propaganda so as to make them more easily acquired by the population, the newly developed field of governmental visual propaganda –as seen in Figure 1 – is a good place to turn (Hoffman, 1934; Le Bon, 1895: 55–56).

Here, we see that, upon a backdrop of clamouring supporters, Adolf Hitler is looking at the reader, with the white text adorning the work stating ‘Ja! Führer wir folgen Dir!’ [author translation: ‘Yes! Leader, we follow you!’] Contextually, this work holds its origins very early on in the rule of the NSDAP (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei – the formal term for the German National-Socialist party) and sought to garner public support for a referendum that aimed to combine the Chancellery and the Presidency of the country. Crucially each part of this poster intended to draw the target audience (usually young men) back to the core themes of the NSDAP, with a particular focus being placed on establishing a Volksgemeinschaft [author translation: people’s community]. This mix between implicit and explicit messaging, alongside the sustained use of core narratives, underlines the importance that affirmation held in German propaganda campaigns. It may certainly thus be proposed that this was a resounding success, given the astronomically high 95 per cent of the estimated 40.5 million who turned out voting in favour of the ascension of Hitler to the post of Führer (Zurcher, 1935: 95). Let us, however, assume a more critical view of this matter. When one takes Le Bon’s theory, a supposition is that the degree of persuasion, and thus success, should be demonstrated through these statistics. Yet this brings us to a striking problem: Le Bon fundamentally supposes that persuasion of the people is the only means through which propaganda may operate, neglecting to consider how individuals may act out of fear. This would, in turn, render it particularly challenging to accurately utilise these statistics as demonstrable proof that the factor of affirmation, in and of itself, can persuade, rather than pressure, individuals into the desired actions. To surmise, through the lens of affirmation, we are certainly able to gain a great deal of nuance in our understanding of propagandistic pieces, yet due to the lack of consideration within Le Bon’s work on potential pressures applied to citizens, it makes it extremely difficult to accurately vindicate his work.

When we turn our attention towards the presence of affirmation within the anti-Semitic propaganda originating in Nazi Germany, we continue to see how the lack of theoretical nuance within Le Bon’s work is cause for concern.

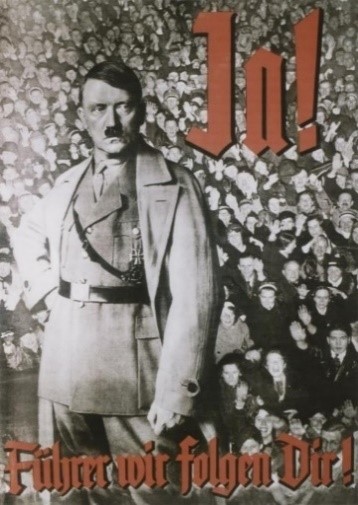

Firstly, one ought to consider Figure 2, as this is a particularly useful means through which this theme can be considered (Hanich, 1940). This work of propaganda depicts the stereotypical, pejorative representation of Judaism in the shadows of the three great Allied powers: the United States, the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom. We can read text which states, ‘Hinter den Feindmächten: der Jude’ [author translation: Behind the Enemy: The Jew]. David Welch, a pre-eminent academic on Germany, describes how, during the 1935 Nuremberg Laws, little serious objection was raised by the Germans towards the deprivation of all Jewish citizens of their rights, with many going so far as to support laws that prevented intermarriage with Jews (Welch, 1987: 415). Hitler had a profound desire to rapidly militarise the German people as a means to sustain a presumably global conflict, and that his ‘definite spiritual convictions’ often hinged upon cohesive unity, and it is perhaps not a far cry to suggest that the manipulation of messaging served to prepare the people for a rabid fight against the Allies, thus vindicating Le Bon’s work (Welch, 1987: 410). Given that academics go so far as to suggest that ‘[w]ithout the silent, intimidated, ambivalent or, in some cases, enthusiastic conformity of an overwhelming majority of German society […] Hitler’s regime would simply not have persisted from 1933 to 1945, much less been able to carry out its murderous policies’, the lack of consideration of the role apathy plays renders Le Bon’s work concerning (Mailänder, 2016: 400). If apathy was so key, and can be presumed to occur across different contexts, the sole consideration of the extreme of society – convincing people to become dogged supporters of a cause – lacks the nuance required to tackle the majority of the population who remain indifferent. For instance, within Figure 2, the categorisation of ‘the Jew’ as being tied to an enemy would possibly result in the fact that moderates within a population would justify the treatment of the Jewish people due to their seeming tie to individuals that appeared to wish harm to the state. Consequently, incentivising the perpetuation of apathy in society so as to prevent dissent was a tool expertly handled by the German state, yet is something that is not seen within Le Bon’s work. To draw to an end this point on affirmation in Nazi Germany, one can certainly suggest that Le Bon’s work does allow for the facilitation of some considerations of the Nazi propaganda machine; however, it fails to consider the importance that apathy can play in enabling the successful enactment of state goals, something that constrains its use today.

Moving onto repetition, the factor, as the name implies, is that of the mass diffusion of government messaging (Le Bon, 1895: 55). This is particularly notable within this appraisal of Le Bon’s work as, given the advent of mass media during the 1920s and 1930s, as well as the now greater disposable income that facilitated the purchase of luxury items, numerous governments sought to innovate upon their domestic radio technologies (Soules, 2015: 63; Welch, 1987: 411). The consistent and repeated application across society, in accordance with Le Bon, is ideally suited to the inculcation of certain ideas and their normalisation. One particular means through which this was undertaken was through the radio. For instance, the Volksempfänger [author translation: lit. People’s receiver] was a particularly cheap radio that, in 1941, could be found in 65 per cent of German households (Rentschler, 2003: 186). This is rendered all the more politically poignant when one considers that Joseph Goebbels (Reich Minister of Propaganda, 1933–45) repeatedly stressed that the only news that ought to consistently be diffused should be that which best served the immediate needs of the government (Soules, 2015: 131). When considered in conjunction with the point on apathy, it may be suggested that utilising such messaging systems to normalise the ideas and arguments of the state was ideally suited to end. This, however, brings to the fore an additional problem with Le Bon’s work. The supposition that one can correlate radio ownership rates, and thus the broad capacity to distribute messages, to the potential success of a propagandistic campaign – whether it be to increase support or to normalise ideas – is one that is largely unable to be confirmed. Additionally, Germany’s participation in the Spanish Civil War served its purpose to propagate anti-Soviet and anti-Marxist rhetoric across Europe, which facilitated its rapid re-armament in the face of ‘Soviet/Bolshevik aggression’ (Bernecker, 1992: 140–43). This very clear focus upon leftist movements may thus be suggested to have been an attempt to justify the casualties and costs associated with the conflict (around 300 soldiers would die over the course of the conflict), while also leveraging support from German Catholics, who were inclined to shirk away from NSDAP rhetoric (Thomas, 1977: 977; Welch, 1993: 4). If we look at the newspaper Völkischer Beobachter’s [author translation: The People’s Observer], we see how the government-affiliated newspaper would publish titles such as ‘Moskau funkt: „Tötet alle Priester!”‘ [author translation: Moscow Intercepted: ‘Kill All Priests!’] and other increasingly polemic headlines as its circulation rates leapt from 100,000 in 1931, to over 1.1 million in 1941 (Anon, 1936a; Layton Jr., 1970: 362). Yet once again, through the lens of Le Bon’s work, one struggles to find a direct correlation between each of these points, as one cannot comment in good faith on the success of such campaigns without any definitive correlation. This simply once again demonstrates, through a different form of media, how the repetition aspect of Le Bon’s work – while definitely a pre-eminent part of the German propagandistic campaign, and which certainly facilitates the interesting political analysis of these sorts of initiatives – fails to provide an academically concrete means of determining the successes of such campaigns.

Finally, Le Bon asserts that contagion is the final step in creating successful propaganda, an argument that requires a more nuanced understanding of the constitutive parts of human psychology. This concept is predicated upon the belief that the sentiment of being excluded will ultimately, and inevitably, draw individuals to join social, cultural, religious or ideological groupings, whether these be run by the state directly or through third parties (Le Bon, 1895: 56). The logical progression of this argument is that the consistent membership growth of any kind of group will typically result in its exponential growth, which is related to the ever-increasing social expectation to join. While this is not always an easy process to perceive in practice, one can turn to the popularity of the Hitler Youth, and how its gradual militarisation created a near fanaticism for Hitler (Horn, 1979: 642–45; Kunzer, 1938: 346–49; Welch, 1993: 4). If we are to consider propaganda posters that fomented this attitude, we can turn to one that depicts a young Aryan boy stood looking towards the Führer, with the text emblazoning the work stating ‘Jugend dient dem Führer – Alle Zehnjährigen in die HJ’ [author translation: Youth serves the leader – all 10 year olds into the Hitler Youth] (Anon, 1941). The relative success of this idea, and thus Le Bon’s argument, is slightly problematised when we consider membership figures of the group. In 1933, there were approximately 7,529,000 who formed part of the organisation, a number that would only increase to 7,728,259 in 1939. The consequence of this is that, in accordance with Le Bon’s theory, one would expect an exponential rise in membership, yet this failed to take place, with most of these 200,000 or so boys only joining when governmental pressures began to reach their crux. While one is loathe to give too much credit to Hitler, given the aforementioned theories he espoused in Mein Kampf, he suggests that, at a certain point – when the assumption of ideas begins to stagnate within society – direct government force must be used (namely, suppressing dissidents directly, or forcing people to assume or accept ideas) (Hitler, 1924: 148–49). This does, given Le Bon’s theory as a baseline, seem to add some nuance to his ideas within the framework of authoritarian regimes. Additionally, it may be suggested that a novel interpretation of Le Bon’s work may well help resolve some of the aforementioned problems associated with localising the impact of societal pressure (and, therefore, fear) within his work. If we are to broaden our understanding of contagion beyond the concept of solely a draw to joining organisations due to exclusion to one of joining out of societal pressures, then Le Bon’s work becomes far more intuitive. This would allow for us to thus understand the membership rates to be characterised by an initial phase of rapid joining from the activities and advantages provided to boys. Following this, not only would boys begin to join out of a desire to form part of this fraternal group, but some may join (or be encouraged to join by their parents) from the societal pressures and fears of being persecuted for not being a part of this grouping. It thus follows that from the moment that such membership rates begin to slow in adherence, the government steps in to continue this growth to suit its end of ideological manipulation. This more nuanced, and novel, view of contagion may then be suggested to render Le Bon’s work far more pertinent to the current environment, and a more effective tool for studying propagandistic campaigns.

To conclude this preliminary section, Le Bon’s work may well be interpreted as a sociological piece that is firmly located in its period of publishing. Because of this, and its inability to conceive of the capacity for the state to rely upon fear to ensure the success of its propagandistic campaigns, Le Bon’s work suffers from solely focusing on the persuasive elements of propaganda. This can be countered, however, through a broader consideration of his point on contagion, as expanding it to include instances of pressure (usually fear) helps resolve several problematic aspects of his work. As well as this, his work, along with those more broadly in the theoretical propaganda sphere, ultimately fails at providing a proper means of demonstrating the success of a propagandistic campaign. For this reason, it may be proposed that Le Bon’s work is far more suited to enabling the more precise evaluation of propagandistic campaigns through its three-step process. One may then suggest that Le Bon’s work is of most use within the contemporary era when utilised as an analytical and descriptive tool, rather than as a methodological process through which to approach the successes of propaganda.

Having appraised Le Bon’s work, and drawn out a novel reinterpretation of this, it will be particularly fascinating to consider the Spanish propaganda context both at a macro and micro scale so as to demonstrate the utility of his work while better understanding a relatively lacking sector of scholarly consideration.

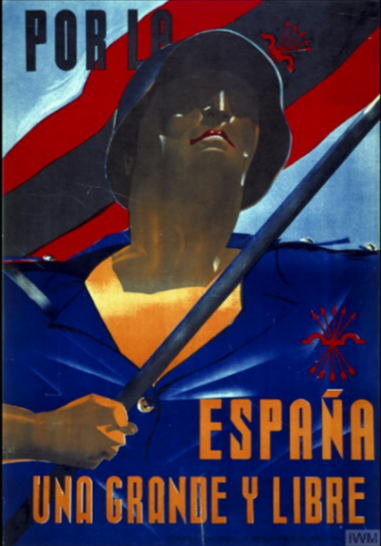

A strong man dressed in Falange uniform waves the party flag while wearing the military uniform of the time. We see the core aspects of Franco’s ideology – notably the need for strong young men who would uphold traditional values. Figure reproduced in accordance with Accepted Non-Commercial Use Permissions, sourced from the Imperial War Museum.

Let us firstly turn back to affirmation. One slogan that epitomised Francisco Franco’s idealised Spain is ‘Una, Grande y Libre’ [author translation: One, Great and Free] (Pinto, 2004: 657). Figure 3 is an exemplary example of how such simple affirmations were ideally suited to being integrated into propaganda posters, an information-diffusion technology that had only just undergone rapid technological developments (Anon, 1936b). Within this work, the imagery itself helps to draw in the audience as – from the highly recognisable blue shirt of the Falange uniform (the extreme right-wing nationalist political party/coalition over which Franco presided[4]) to the anonymised man upholding his country’s pride – both entice naïve viewers to identify themselves with the figure. This, in turn, interweaves a plurality of messages into one coherent narrative, ultimately drawing people against the enemies of the state through sacrificing individuality for the country and forming a newly unified Spain under the auspices of socio-economic conservatism. Such concise messaging is particularly compounded by the figure waving the Falange’s flag – one that holds a striking resemblance to that of Spain prior to the Segunda República Española (1931–1939) – the democratic government that had moved away from previous religious norms.[5] To any rational observer, one can understand that this poignant commentary depicted the future of Spain as being ultimately tied to the tradition that preceded the period of relative economic instability under democracy. One ought to also consider the fact that while the Nazi party had originally won elections, which meant propaganda largely aimed to gain consent for the expansion of totalitarian power, Franco was forced to justify the unsuccessful Nationalist coup as well as the Spanish Civil War so as to legitimise his power, while also attempting to unify the country and consolidate nationalist ambitions (Cobo Romero, Ángel del Arco Blanco and Ortega López, 2011: 46). This would come to underpin the majority of the propaganda that could be seen in Spain, with the former propaganda piece being a striking example of this. This unity – whether within the family, or in Spain more broadly – became a tenet of the Spanish system. It is thus perhaps due to these promises and ideas, which were within the deliverance capacity of the state, that the potency of the Falange’s capacity to accrue ever greater support would develop. One has but to turn towards the membership figures of the organisation to see this perspective vindicated as – following the Spanish Civil War – its membership exploded to well over one million members, a colossal increase from the 10,000 or so prior to the war (Slaven, 2018: 235–39).

Of course, while one must have a strong message, it would be reductionist to posit that the membership figures exemplify the sole importance of affirmation in the governmental process. For instance, a striking problem with the utilisation of such propaganda posters, and the attempt to distribute political prospectuses to garner support for the Nationalist government, was the appallingly poor Spanish literacy rate. Recent studies outline how only 37 per cent of the population in the 1940s were literate, with this illiteracy particularly being among women and countryside dwellers (Gómez García and Cabeza San Deogracias, 2013: 107). As a consequence, and in contrast to Germany, Spain was forced to find new ways of distributing their propaganda messages. For instance, audio-visual technologies became all the more prominent – and important – in the consistent and perpetual diffusion of news and ideas, with films in particular being a key means of doing this. The film Raza is one of the most striking instances of propaganda within Spain at the time (Sáenz de Heredia, 1941). In and of itself, it was an elaborate Nationalist retelling of the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s life, depicting hyper-masculinity, religion and the need for unity, all through a framework of hierarchy in which the viewer would situate themselves (Higginbotham, 1988: 19–20). For example, within the film, we see how the brother of the family (now commonly believed to symbolise Franco’s own brother) turns his back on his country and family through his presumed support of the enemy. Given that it is now understood that a variety of social classes of the Spanish flocked to cinemas as a means of escaping the hardships of daily life, the government were thus provided with an ideal means of targeting a large and politically diverse domestic audience in its campaigns (Richardson, 2011: 101). Not only this, but the Noticiarios y Documentarios (NO-DO) [official translation: News and Documentaries] that appeared prior to all visual-media-presented biased news that aimed to monopolise the possible sources from which messaging could be repeated and subconsciously assumed by attendees. It may thus be suggested that this continual wearing down of the people within their leisure time proved to be the optimal location in which one could gradually wear down the resistance of the populous, and instil apathy within them. Within the framework of Le Bon’s work, we are able to clearly see the means through which such repetition, particularly of the strikingly pertinent ideas held by the government, contributed to the stark jump in membership figures.

Considering the specific means through which incidental exclusionary tactics held a role in growing the support of women for Franco’s Spain could also help us assess the importance of contagion in gaining a greater understanding of a propaganda campaign. Whereas women theoretically had the same legal rights as men during the German Weimar Republic (1918–1933), and ‘chose’ to cede them to the extremely conservative NSDAP, Spanish women were not in the same position.[6] Following the Second Republic and the Civil War, women – who had held the right to suffrage and (broadly) the same labour rights as men – involuntarily saw fundamental emancipatory legislation get repealed (Lannon, 1990: 213–14). For this reason, Franco recognised that the Sección Femenina (author translation: Female Section) – a social club-cum-propaganda dispensary – could be used to parrot the state rhetoric on the importance of femininity and fascism in the creation of a ‘perfect’ woman, teaching skills that would serve to maintain the household (Ofer, 2005: 667–69). In a similar vein to the aforementioned Hitler Youth poster, we can turn to the magazine cover of the Revista para la mujer nacional-sindicalista (No.15; February 1939) [author translation: ‘The Magazine for the National-Syndicalist Woman’], a magazine designed and published by the Sección Feminina (Anon, 1939). Here, we can see three women, each one representing a distinctly feminine profession, with two of them presenting the fascist salute towards the left of the poster, while the third wears an apron emblazoned with the Falange symbol. This is of great interest to us, given that it helps to understand the purported notion that not only were there specific jobs intended for women (such as being a nurse), but that for a woman to be deemed a ‘real woman’, she was to embrace government within her day-to-day routines, which ensured her subservience to patriarchs. To add to this, women who dissented from typical societal norms were usually exiled, imprisoned or executed by vigilantes or the government (Lannon, 1991: 215). This allows us to suggest that, under the broader interpretation of Le Bon’s contagion, the exclusionary nature of this group, coupled with the threats of violence and harassment, provided prominent push-pull factors for women to adhere to such groups. While membership figures are unfortunately unknown, the former statistics on membership research of the Falange allow for further consideration to take place. For instance, it is certain that the previously mentioned affirmation and repetition would have instilled either passion for, or apathy towards, the party, yet the group sentiment and unrestricted violence against non-adherents will have likely pushed some men to sign up. Additionally, it is not a far cry to suppose that some were obligated to do so following threats to their families, themselves or their local community. Thanks to this novel conception of Le Bon’s work, it may certainly be proposed that this allows for greater nuance to be retained when considering the sociological factors affecting adherence to a group.

In conclusion, upon thoroughly deconstructing the ideas of Le Bon within the context of Nazi Germany, and drawing out both the relative advantages and disadvantages of his ideas, it has been possible to demonstrate the utility of his ideas within the context of fascist Spain. Over the course of this work, it has been demonstrated that utilising Le Bon as a theory of approaching propaganda provides a systematic tool through which to analyse these sorts of processes. This can facilitate the detailed consideration of propagandist intentions – as well as the sociological impact upon the people – by means of certain tools. Unfortunately, his work has struggled to maintain full pertinence within the contemporary environment, primarily due to the onset of systematic targeting of civilians within conflict and the suppression of dissident voices, thus requiring a new consideration of his point on contagion. Thanks to this novel reinterpretation of his work, one is able to include greater flexibility in the means through which one approaches the attitudes of the people, as both persuasion and the pressure they may feel can influence such decisions. Once this is applied to often-overlooked contexts, such as that of Spain, one has the ability to view the nuance of public reactions to propagandistic campaigns, drawing out new insights that may have been overlooked. A limitation of Le Bon, and studies on propaganda more broadly, is the inability to clearly demonstrate the success of a propagandistic campaign, primarily due to academically problematic opinion polls or inaccessible data. For this reason, one might suggest that Le Bon is better suited as a means of drawing insight from propaganda campaigns as a theory, rather than being used to quantify their successes. In the years to come, further academic study on the means through which one might critically evaluate the successes of propaganda would reinvigorate the academic field and continue to provide insights into contemporary propagandistic campaigns.

A special thanks to Juliane Walther for kindly helping to provide concise summaries and clarifications of some German-language sources that were of particular use within the preliminary stages of research for this article. I also wish to thank Dr Leticia Villamediana Gonzalez for her consistent support throughout the research and writing process of this piece; it would not have got to this point without her continued guidance.

Figure 1: Ja! Führer wir folgen Dir!

Figure 2: Hinter den Feindmächten: der Jude.

Figure 3: Por Una España Una, Grande y Libre.

[1] It is worth noting that whilst Le Bon depicted these as stages, these are not to be considered as self-contained units, and may very well be used all at once, or vary in strength over time.

[2] For copyright reasons, not all could be included within this document, but remain worth consulting for purposes of clarity.

[3] This book formed the cornerstone of his beliefs, and remains important within fascist and neo-fascist groups as a vindication of the discrimination of other social and ethnic groups. Since its publication, it is now widely recognised that the text greatly embellishes Hitler’s life, and exaggerates his military accolades as a means of justifying his sought after ‘strong man’ identity, coupled with convoluted theoretical rants.

[4] The agglomerated political groups that made up the Falange were plagued with divisions throughout its history, although remained the dominant far right political force in the country, going so far as to be subsidised by Italy’s fascist regime. Whilst initially, Francisco Franco would not have direct engagements in the party, after seizing power in April 1937, he would forcefully unify the Falange with a Carlist party in a bid to create unity that would accentuate the success of the Nationalist’s war effort, and would eventually become the only legal political party in Spain (under Franco’s supervision).

[5] A stage of Spain’s history characterised by the deposition of King Alfonso XIII in 1931. A (broadly speaking) politically progressive and democratic period plagued by economic turmoil (accentuated by outside pressures) and political instability. Extremely reformist in nature, the rapid changes between left and right-wing parties led to embitterment, sectarianism and political assassinations during this period. This vindicated the growing dominance of the military, who went on to fracture and eventually turn against the Republican regime at the time, leading to the Spanish Civil War and Francisco Franco’s rise to power. The legacy of political controversy has continued to plague Spain’s political discourse, and is a key component of the brutal crackdowns undertaken by Franco.

[6] For further reading on women and their rights under the Weimar Republic, and why they overwhelmingly voted for the NSDAP, I highly recommend Helen Boak’s chapter ‘Women in Weimar Germany: The “Frauenfrage” and the Female Vote”‘ in Social Change and Political Development in Weimar Germany (Bessel and Feuchtwanger, 2019).

Anon. (1936a), ‘Moskau funkt: „Tötet alle Priester!”‘, Volksgemeinschaft: Heidelberger Beobachter, 20 August 1936 (Copy 230), pp. 1–13 (p. 1), from ‘Heidelberg historic literature – digitized’, Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, available at https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/volksgemeinschaft1936a/0729, accessed 4 January 2021.

Anon. (1936b), ‘Por La España Una, Grande y Libre’, Jefatura Nacional de Prensa y Propaganda, Sección Mural, available at https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/41993, accessed 6 December 2021.

Anon. (1939), ‘Revista para la mujer nacional-sindicalista’, from La Biblioteca Virtual de Castilla-la Mancha – Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha, No. 13, Madrid: Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las J.O.N.S. – Sección Femenina, February 1939, available at http://hemerotecadigital.bne.es/issue.vm?id=0027340260&search=&lang=en, accessed 27 July 2022.

Anon. (1941), Jugend dient dem Führer – Alle Zehnjährigen in die HJ, Berlin: Presse-und Propagandaamt der Reichsjugendführung, from Library of Congress, available at https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/93500159/, accessed 16 January 2021.

Hanich, B. (1940), ‘Hinter den Feindmächten: der Jude’, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, available at https://geheugen.delpher.nl/en/geheugen/view?coll=ngvn&identifier=NIOD01%3A494 20, accessed 13 January 2021.

Hoffman, H. (1934) ‘Ja! Führer wir folgen Dir!’, Reichspropagandaleitung der N.S.D.A.P, available at https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn3737, accessed 5 December 2021.

Sáenz de Heredia, J. L. (1941), Raza, Cancilleria del Consejo de la Hispanidad & Ballesteros.

Bernecker, W.L. (1992), Alemania y la Guerra Civil Española, Bernecker W.L. (ed.), Frankfurt: Vervuert Verlagsgesellschaft, pp.137-58 (pp.140-43), available at https://doi.org/10.31819/9783964562326-008, accessed 31 December 2021].

Boak, H. (2019), ‘Women in Weimar Germany: The “Frauenfrage” and the female vote’, in Bessel R. and E. Feuchtwanger (eds), Social Change and Political Development in Weimar Germany, London: Routledge, p. 155–73, available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt18mvkrj, accessed 29 December 2021.–

Cobo Romero, F., M. Ángel del Arco Blanco and T. María Ortega López (2011), ‘The stability and consolidation of the Francoist regime. The case of Eastern Andalusia, 1936–1950’, Contemporary European History, 20 (1), pp. 37–59 (p. 46), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/41238342, accessed 7 December 2021.

Ellul, J. (1965), ‘Propaganda: The formation of men’s attitudes’, Kellen, K. and J. Lerner, (trans.), Paris: Armand Colin, pp. 25–32 (p. 25), available athttps://monoskop.org/log/?p=2603, accessed 5 December 2021.

Evans, R. (2007), ‘Coercion and consent in Nazi Germany’, British Academy Review, 10, pp. 53–81 (p. 54), available at https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/2036/pba151p053.pdf, accessed 6 December 2021.

Gómez García, S. and J. Cabeza San Deogracias (2013), ‘Oír la radio en España. Aproximacón a las audiencias radiofónicas durante el primer franquismo (1939–1959)’, Historia crítica, 50, pp. 104–31 (p. 107), available at https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4351474, accessed 4 January 2021.

Higginbotham, V. (1988), ‘Early postwar film: 1939–59’, in his Spanish Film Under Franco, Austin: University Texas Press, pp. 18–30 (pp. 19–20), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7560/775916 , accessed 16 January 2021]

Hitler, A. (1924), Mein Kampf, trans. J. Murphy, greatwar.nl, pp. 1–557(p. 149), https://greatwar.nl/books/meinkampf/meinkampf.pdf, accessed 12 March 2023.

Horn, D. (1979), ‘Coercion and compulsion in the Hitler Youth, 1933–1945’, The Historian, 41 (4), pp. 639–63 (pp. 642–45), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/24443528, accessed 5 December 2021.

Jowett, G. and V. O’Donnell (2019), ‘How to Analyze Propaganda’, in Propaganda and Persuasion, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 267–83 (p. 267), available at https://us.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-assets/102172_book_item_102172.pdf" https://us.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-assets/102172_book_item_102172.pdf, accessed 11 January 2021.

Kershaw, I. (1994), ‘The “Hitler myth”: Image and reality in the Third Reich’, in Nazism and German Society 1933–1945, London: Routledge, pp. 137–48 (p. 144), available at https://www.routledge.com/Nazism-and-German-Society-1933-1945/Crew/p/book/9780415082402 , accessed 7 December 2021.

Kunzer, E. (1938), ‘The youth of Nazi Germany’, The Journal of Educational Sociology, 11(6), pp. 342–50 (pp. 346–49), available at https://doi.org/10.2307/2262246, accessed 30 December 2021.

Lannon, F. (1991), ‘Women and images of women in the Spanish Civil War’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 1, pp. 213–28 (pp. 213–15), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/3679037, accessed 17 January 2021.

Layton Jr., R. (1970), ‘The Völkischer Beobachter, 1920–1933: The Nazi Party newspaper in the Weimar Era’, Central European History, 3 (4), pp. 353–82 (pp. 360–62), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/4545584, accessed 14 January 2021.

Le Bon, G. (1895), ‘The crowd: A study of the popular mind’, International Relations Security Network, esp. pp. 55–60, available at https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/125518/1414_LeBon.pdf, accessed 7 December 2021]

Le Bon, G. (2007), ‘Psychologie des foules’, Project Gutenberg EBook, pp. 112–17, available at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/24007/24007-h/24007-h.htm, accessed 24 December 2021.

Mailänder, E. (2016), ‘Everyday conformity in Nazi Germany’, in Corner, P. and J. H. Lim, (eds.), Palgrave Handbook of Mass Dictatorship, London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 399–411 (p. 400), available at: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-43763-1_32, accessed 7 March 2023.

Margoli, M. (1984), ‘Public opinion, polling, and political behaviour’, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 472, pp. 61–71 (p. 64), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/1043883, accessed 8 January 2021.

Ofer, I. (2005), ‘Historical models – contemporary identities: the sección feminina of the Spanish falange and its redefinition of the term “femininity”‘, Journal of Contemporary History, 40 (4), pp. 663–74 (pp. 667–69), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/30036353, accessed 23 December 2021.

OMGUS (1970), ‘German views on denazification’, Report No. 182 (11 July 1949), (Frankfurt-am-Main: Office of Military Government, United States, 1949); in Merritt, A. and R. Merritt (eds.), Public Opinion in Occupied Germany: The OMGUS Surveys, 1945–1949, Champaign: University of Illinois Press, pp. 304–06 (p. 305), available at https://libsysdigi.library.uiuc.edu/OCA/Books2009-07/publicopinionino00merr/publicopinionino00merr.pdf" https://libsysdigi.library.uiuc.edu/OCA/Books2009-07/publicopinionino00merr/publicopinionino00merr.pdf, accessed 11 January 2021.

Pinto, D. (1977), ‘Indoctrinating the Youth of Post-War Spain: A Discourse Analysis of the Fascist Civics Textbook’, Discourse and Society, 15(5), pp.649–667 (p.657), https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926504045036, accessed 8 January 2021].

Rentschler, E. (2003), ‘The fascination of a fake: The Hitler diaries’, New German Critique, 90, pp. 177–92 (p.186), available at https://doi.org/10.2307/3211115, accessed 8 December 2021.

Richardson, N. (2011), Constructing Spain: The re-imagination of space and place in fiction and film, 1953–2003, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press, pp. 32–69 (pp. 35–36), available at https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781611483963/Constructing-Spain-The-Re-imagination-of-Space-and-Place-in-Fiction-and-Film-1953%E2%80%932003 , accessed 25 December 2021.

Slaven, J. (2018), ‘The Falange Española: A Spanish Paradox’, 10th Annual RAIS Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities, 211, pp. 235–42 (pp. 235–39), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3266916, accessed 8 December 2021.

Soules, M. (2015), ‘Public opinion and manufacturing consent’, in Media, Persuasion and Propaganda, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 55–77 (pp. 63–64), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1g09zzm, accessed 7 December 2021.

Thomas, H. (1977), ‘Appendix Seven: An Estimate of Foreign Intervention in the Spanish Civil War’, in The Spanish Civil War, 3rd edn., Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd., pp. 974–85 (p. 977).

Welch, D. (1987), ‘Propaganda and indoctrination in the Third Reich: Success or failure?’, European History Quarterly, 17(4), pp. 403–22 (p. 410–15), available at https://doi.org/10.1177/026569148701700401, accessed 8 December 2021.

Welch, D. (1993), ‘Manufacturing a consensus: Nazi Propaganda and the building of a “national community” (Volksgemeinschaft)’, Contemporary European History, 2 (1), pp. 1–15 (pp. 4–13), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/20081463 Accessed 20 December 2021.

Zurcher, A. (1935), ‘The Hitler referenda’, The American Political Science Review, 29 (1), pp. 91–99 (p. 95), available at https://doi.org/10.2307/1947171, accessed 8 December 2021.

Falange: The National Socialist, and later far-right conservative and traditionalist, party that was the amalgamation of a plurality of right-wing political parties, with the major mergers dating from 1934, and 1937, with its final official name being ‘Falange Española Tradicionalista de las JONS’ (FET y de las JONS).

L’affirmation: (Affirmation) The first ‘step’ required for the successful dissemination of ideas on the part of a state within a population. The first ‘stage’ of this process involves the utilisation of short, succinct messaging to provide an impact tailored to suit the targeted demographic. In practice, this would usually take the shape of slowly changing the messaging of propaganda to tailor public opinion, or inculcate desired ideas through presenting new themes that consolidate the ideals.

La contagion: (Contagion) The final of the three ‘stages’ of Gustave Le Bon. This stage is the hardest to measure, and relies upon the belief that ‘herd mentality’ – the movement of peoples towards large groupings to prevent exclusion – is a means of influencing a people. In practice, this would mean creating government-led groups and, over time, participation would (in theory) expand exponentially.

La répétition: (Repetition) The second of the three ‘stages’ proposed by Gustave Le Bon. The means through which a state would seek to establish mastery through the repeated promotion of the previously mentioned affirmations. This constant messaging would, in theory, allow for the populous to gradually absorb ideas; their normalisation would occur through media sources, education and common discourse.

Mein Kampf: Written by Adolf Hitler in 1925; an autobiographical account of his life, whilst featuring his musing on the world and the intended legitimisation of his views on the purported superiority of Germanic peoples.

Noticiarios y Documentarios (NO-DO): (Official translation: News and Documentaries) Newsreels that appeared before all films shown in Spain from 1943 until 1981. Developed by the government to bring to the fore the positive aspects of the news to the Spanish people, they predominantly focused on infrastructure projects, censored reports on international news, or the goings-on with the state.

NSDAP (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei): (National Socialist German Worker’s Party) Founded in 1920, Adolf Hitler assumed control in 1921, which led famous violent anti-government movements along alt-right lines of thought. These ideals manifested themselves in anti-Semitism, German pride (for instance, decrying the Versailles treaty), anti-Marxism, and a need for economic reform. In July 1932, they gained over one-third of the seats in the parliament, and Hitler became Chancellor the following year, establishing the Nazi government until the end of the Second World War.

Revista para la mujer nacional-sindicalista: (The Magazine for the National-Syndicalist Woman) Published between 1938 and 1945, this was a monthly publication created by the Sección Femenina that discussed all major topics that were deemed to concern women, (e.g. the best norms to follow to be the best wife or mother, or how to best sew).

Sección Femenina:(author translation: Female Section) Organisation known as the women’s branch of the Falange; developed by the sister of Spain’s former dictator, Pilar Primo de Rivera. It sought to instil traditional values and norms within women (such as teaching how to sew, how to be a good housewife, and how to best raise your children correctly). Unsurprisingly, the limited freedoms of women made this an appealing means through which to socialise with other women without requiring the husband’s permission. The ability to get basic permits were dependent upon their participation in the group.

Völkischer Beobachter: (‘The People’s Observer’) Newspaper published nationally as part of the NSDAP media-wing from 1920 until the end of the Second World War. Given its proximity to Nazism, and later the government, it became key in influencing public opinion and controlling the information that would reach broader society.

To cite this paper please use the following details: Galbraith, B. R. (2023), 'An Appraisal of the Work of Gustave Le Bon Within the Case Studies of Fascist

Spain (1936–1975) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945)', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 16, Issue 1, https://reinventionjournal.org/article/view/1196. Date accessed [insert date].

If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.