Carissa Samuel, Ranbeer Singh, Manal Ahmed, Vaidehi Gupta, Setareh Harsamizadeh Tehrani, Michelle Hom, Nikhita Kandikuppa, Emily Nguyen, Lilly Nusratty, Anusha Sharangpani, Ma Thae (Juliana) Su, Ohlone College, USA

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are linked to an increased risk of health challenges. This study looked at a diverse sample of students at Ohlone College, a community college in the California Bay Area, to 1) analyse the ethnic groups with the highest ACEs scores and 2) examine the relationship between ACEs and indicators of mental health, including depression, substance-use disorders and self-worth. Using a unique approach to study ethnic identity by incorporating more distinguished ethnic groups, rather than broad categories, our survey found that the two ethnic groups with the highest average ACEs scores were the Afghan American (n = 226) and Native American (n = 229). These two communities, along with the Middle Eastern/North African (MENA) American (n = 228) community, were studied. Through comparison, individuals with high ACEs scores were found most likely to also have higher PHQ-9 scores, higher substance-use disorder symptoms and lower self-worth scores. We concluded that the various societal impacts of ethnic-identity groups must be prioritised as an important facet of mental health. If ethnic identity is included as part of early intervention in situations with abuse and neglect (diagnosis and/or prevention), it may greatly reduce the risk of mental illness.

Keywords: ACEs, Adverse Childhood Experiences, Ethnic identity and mental health, depression and ACEs, self-worth and ACEs, substance-use disorder and ACEs

Distinct trends in mental health difficulties can be found within various ethnic-identity communities (Lee and Chen, 2017). One main driver of these trends is Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) faced by individuals from various backgrounds. Understanding and analysing these trends can be crucial for developing better policies at all levels as well as identifying necessary policy and treatment reform with therapy more focused on past trauma. We found that three facts about these ACEs highlighted the importance of this study.

Firstly, ACEs are often undiscovered and untreated, particularly among specific ethnic groups. Secondly, limited studies have looked at distinct ethnic groups, especially minority groups, who have higher ACEs. These few studies demonstrated that ACEs disproportionately affect the well-being of certain ethnic groups due to factors such as culture, financial status and access to resources. Some of the most understudied groups include Middle Eastern/North African (MENA) American, Afghan American and Native American communities. We were unable to find any studies related to the MENA or Afghan communities but found four studies on PubMed considering Native American ACEs and mental health. Thirdly, there remains a smaller base of ACEs research regarding mental health, creating a lack of documentation on the extent of their impacts, especially when considering ethnic identity. Despite this, multiple studies have confirmed that ACEs do have a substantial impact on individuals, both for their physical and mental well-being (Anda et al., 2002; Assini-Meytin et al., 2021; Crandall et al., 2019; Dube et al., 2001, 2002a, 2002b, 2003; Felitti et al., 1998; Karatekin, 2017; Leza et al., 2021; Merrick et al., 2017; Sahle et al., 2022). A few other studies have looked at specific ethnic groups, especially minority groups, who have faced more of these experiences, on average, as shown below.

Looking at these three ACEs characteristics, we hypothesised that studying ACEs scores could provide insight into how likely members of an ethnic group would be to experience high levels of depression, substance-use disorder and low levels of self-worth, focusing specifically on the Afghan American, Native American, and Middle Eastern/North African-American communities.

Historically, depression and substance-use disorder have both been associated with lower levels of mental well-being, while higher self-worth has been associated with higher levels of resilience and flourishing as shown in the studies below.

With the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study, which ran from 1995 to 1997, the study of ACEs entered a new dimension. The study showed that early adversity has lasting impacts on the physical and mental health of individuals, including increasing the risk of lung disease, liver disease and suicide (Schilling et al., 2007). Subsequently, many researchers like Nadine Burke Harris, the current Surgeon General of California, linked Adverse Childhood Experiences (or ACEs) to various health issues. Although there have been countless studies on ACEs after this initial study, there has been a gap in the literature in studying the impact of ACEs on college students’ mental health, especially in regards to ethnic identity. To understand the past research conducted, a literature review was conducted.

ACEs do impact mental health outcomes across the population, particularly for young adults. Research shows that those who have experienced multiple ACEs are linked with a higher risk of substance-use disorder and depression levels. In a study by Mersky et al., (2013), the researchers concluded that the impacts of ACEs on young adults quickly translate to long-term health concerns. Another study found that ACEs were associated with depressive symptoms, drug abuse and anti-social behaviour (Schilling et al., 2007).

In conjunction, ACEs can lead to lower levels of self-worth in young adults due to a lack of attention from their caregivers (Oshri et al., 2014). In comparison, adolescents with ascending self-worth scores showed positive growth and fewer substance-use disorder symptoms compared to those with descending self-worth. There are clear connections between the level of ACEs experienced and negative mental health outcomes – requiring a better, more nuanced understanding of ACEs.

Due to the differences in experiencing and responding to ACEs with differing environments, resources and support systems, there are inequities across various social groups (Thoits, 2010). This makes studying ACEs and their impacts more important, especially when considering the path towards creating equity at a systemic level. ACEs also reveal the necessity of resilience, which is the ability of individuals to respond positively to challenges they have faced in the past. Self-esteem or self-worth have long been shown to have a positive intervening effect on adverse experiences (Marriott et al., 2014). Examining self-worth measures alongside ACEs highlights this aspect of self-worth.

The current literature around ACEs and ethnicity has several limitations, from the population focus to methods. For example, the CDC-Kaiser study only focused on a mostly White population. In the past decade, ACEs studies have evolved and have thus focused on specific ethnic groups. Some of these groups have been studied previously regarding their ACEs and mental health, such as the African-American population and the Native-American population (Brockie et al., 2015; Mersky et al., 2013; Mignon and Holmes, 2013). Although these are studies focused on minority groups, studies such as these are in the minority themselves and are still not holistic, considering multiple variables that may impact these populations. One of the studies on Native American populations focused on grandparents and their concerns about the impact of their culture and lack of resources on their communities’ growing mental health crisis. (Mignon and Holmes, 2013) Another study focused on a specific reservation where they found that many ACEs corresponded to drug use and depressive symptoms, among other impacts. (Brockie et al., 2015) These studies reveal the limited nature of the literature on ethnic groups and ACEs.

Certain ethnic groups have disproportionately higher amounts of ACEs. Despite this, there is a dearth of research focused on ACEs and ethnic groups. These studies have limited generalisability and reveal the lack of literature on diverse ethnic groups as well as the absence of comparisons between ethnic groups to understand the impact of ethnicity itself on ACEs and mental health. Two groups that have been grossly understudied are the Afghan MENA populations in the US (Awad et al., 2019). This is mainly due to them historically having to self-identify as ‘White’ on surveys. As studies have shown, they are not perceived as ‘White’ nor do they perceive themselves as ‘White’. However, this label has resulted in their data being masked and the issues that they face not coming to light (Awad et al., 2022; Maghbouleh, et al., 2022).

Considering the deep interlocking connections between ACEs, depression and substance-use disorder and, consequently, self-worth and resilience, it is clear that these areas need to be studied more. As we were from a community college where research is not usually done, we were able to survey a subsection of the population that is more diverse and less researched. To address the gaps in the literature, we investigated the impact of ACEs scores on depression, substance-use disorder and self-worth among historically under-researched Afghan American, Native-American and Middle Eastern/North African-American communities of a community college, and we hypothesised that different communities would experience ACEs and mental health struggles differently.

Data was collected from 15 to 30 April 2021 using an anonymous online-administered survey system. This survey was conducted on the students of Ohlone College, a community college in California.

The original survey (see Appendix 3) had a total of 43 questions revolving around mental health and ethnic identity. Two questions asked for ethnic identity and its specifics, one asked for gender and sexuality specifics, while the other forty-one questions consisted of previously validated survey questions assessing the following topics: Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), depression, self-worth, substance-use disorder, anxiety, experience during the SARS-COVID-2 pandemic, disabilities, habits and education, self-esteem, perceived stress and suicidal thoughts. But after releasing the survey for about 24 hours, we realised that question 4, which asked about the specifics of respondents’ ethnic identities, would be redundant as question 3 asked for ethnic identity in the form of checkboxes. Therefore, we decided to revise the questions and exclude question 4 while clarifying question 3 about ethnic identities even further. We ended up with a 42-question revised survey (see Appendix 4) with a question on ethnic identity, a question on gender and sexuality, and the other 40 questions regarding the previously mentioned topics.

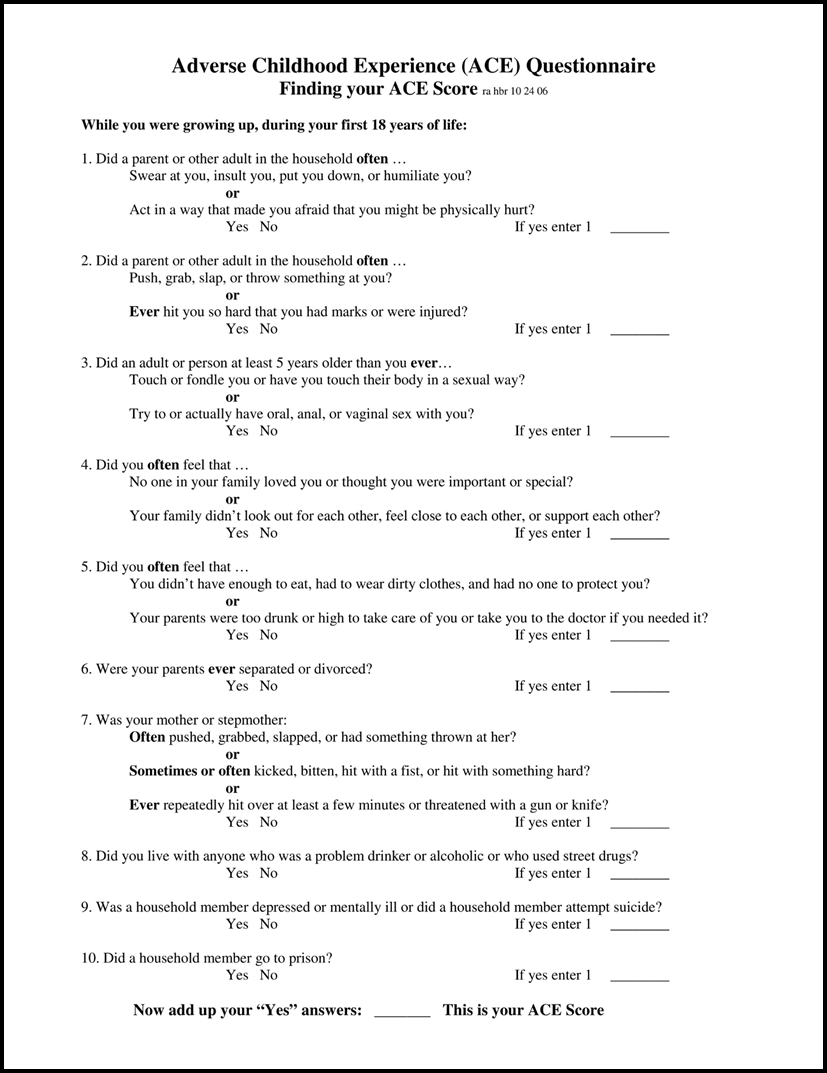

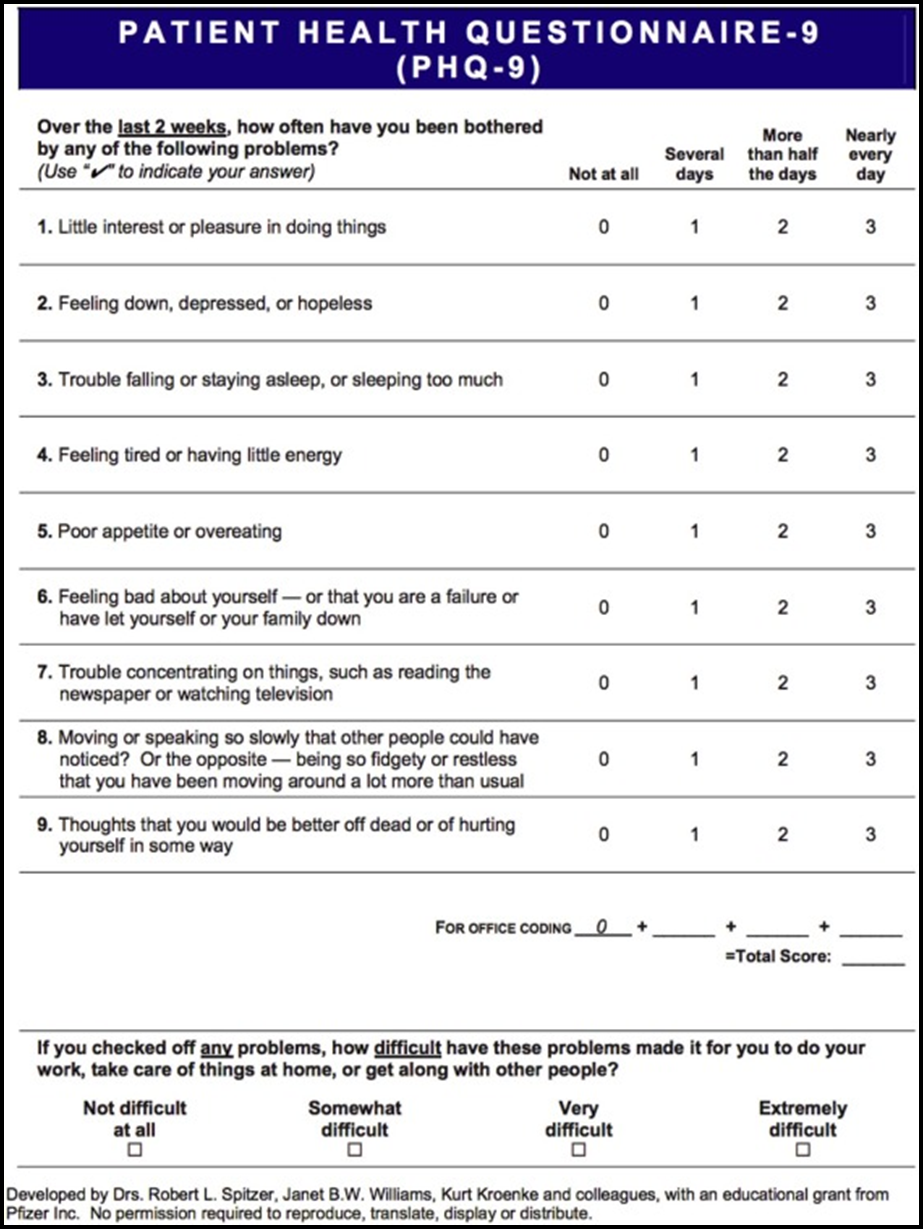

However, for this research, the questions that were focused on were the ACEs, depression, self-worth and substance-use disorder questionnaires. For ACEs, the official CDC-Kaiser Permanente questionnaire was used and all ten questions were included in the survey. (Mueller et al., 2016; Schilling et al., 2007). Regarding depression, the nine official Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) questions were used. (Kroenke et al., 2001). For substance-use disorder, we utilised questions from National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Clinical Trials Network The Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription medications, and other Substance (TAPS) Tool. (McNeely et al., 2016). Self-worth was measured using selective questions from the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). (See Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 for a more visual representation of the questions.) These questions were selected by the entire research team based on which were deemed to be the most appropriate.

ACEs are scored with each negative experience adding 1 point to the respondent’s score. The number of ACEs determines the score (out of 10 possible points/experiences).

The PHQ-9 questionnaire works in a slightly different format. With the score ranging 0–27, each of the nine questions has four options:

So, according to the option selected, the score will differ. Similarly, the options from the TAPS questionnaire (‘Daily or almost daily’, ‘Weekly’, ‘Monthly’, ‘Less than monthly’, and ‘Never’) give insight into the participants’ substance-use habits. Finally, the Rosenberg Scale, like the PHQ-9 questionnaire, uses a method where a number that matches the option selected results in a specific score for each question. A higher score indicates higher self-esteem in individuals.

Since this study served as a way to gather information about diverse ethnic identities that are not primarily discussed, the ethnic identities were detailed in the following way to be clear. These identities were chosen by surveying multiple identity groups across various articles and updating these groups to encompass more diversity. The following identities were:

For the question related to ethnic identity, the participants were allowed to self-report the answers by checking the ethnicities that they identified with, checking ‘all that apply’. For ‘Mixed Ethnic Identities’, it is unknown whether participants checked multiple boxes with or without selecting the ‘Mixed Ethnic Identities’ box as well since the survey site did not keep track of this.

This survey was restricted to only students of Ohlone College and was incentivised. The survey was advertised where the first 200 participants would receive $5 Amazon gift cards. It was a completely anonymous study where the only optional information that was collected was about the individuals who were interested in the gift cards – these respondents choose to provide their email addresses to receive the gift cards. The service that was used to give out the survey blocked any IP addresses and made the server private so that no information was able to be breached.

| TOTAL | Other Asian (Afghan) | American Indian or Alaska Native | Middle Eastern and North African | |||||

| TOTAL | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Male | 625 | 35.27% | 38 | 16.81% | 35 | 15.28% | 34 | 14.91% |

| Female | 647 | 36.51% | 38 | 16.81% | 37 | 16.16% | 40 | 17.54% |

| Trans male | 107 | 6.04% | 36 | 15.93% | 34 | 14.85% | 31 | 13.60% |

| Trans female | 86 | 4.85% | 24 | 10.62% | 30 | 13.10% | 24 | 10.53% |

| Different identity | 96 | 5.42% | 28 | 12.39% | 26 | 11.35% | 24 | 10.53% |

| Gender nonconforming | 112 | 6.32% | 27 | 11.95% | 38 | 16.59% | 37 | 16.23% |

| Prefer not to say | 98 | 5.53% | 35 | 15.49% | 29 | 12.66% | 38 | 16.67% |

| Other (please explain) | 1 | 0.06% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Total respondents | 1772 | 226 | 229 | 228 | ||||

Along with the information presented in Table 1, the survey received responses from individuals who identified themselves according to the options listed above. The responses were White (n = 696, 39.28%), Hispanic, Latino or Spanish (n = 362, 20.43%), Black or African American (n = 479, 27.03%), East Asian (n = 310, 17.49%), Southeast Asian (n = 285, 16.08%), South Asian (n = 275, 15.52%), Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (n = 229, 12.92%), Mixed Ethnic Identities (n = 231, 13.04%), and ‘Some other race, ethnicity or origin’ (n = 2, 0.11%).

According to Table 1, the transgender population makes up more than 10 per cent of the participants of the survey. This is significantly higher than the expected 0.7 per cent, based on US national data of 18- to 24-year-olds (World Population Review, n.d.). Multiple factors may have contributed to this over-representation. Since Ohlone College is located in the San Francisco Bay Area, which is extremely diverse, there may be a higher amount of trans-identifying students (An Equity Profile of the Nine-County San Francisco Bay Area Region, 2017). Continually, since underserved minorities tend to attend community colleges, more individuals from the trans-identifying minority community may be attending Ohlone. Lastly, due to the anonymous nature of the survey, where participants may feel more comfortable sharing their identities, there may have been more individuals who self-reported as trans. This may result in higher levels of mental health difficulties reported as previous studies have found that individuals who identify as transgender tend to face more difficulties throughout their lives (Mueller et al., 2017; Strauss et al., 2020). Overall, however, since our study is not focused on gender, this data does not impact the results significantly.

To understand the relationships between the number of ACEs individuals experienced and their PHQ-9, substance-use disorder and self-worth scores, a statistical analysis was conducted. Keeping the number of ACEs as the independent variable, PHQ-9, substance-use disorder and self-worth scores were graphed as the dependent variables. The overall data was graphed by the number of ACEs by looking at the average scores for all three dependent variables among individuals with each ACEs score. The same procedure was repeated for each of the selected ethnic groups: MENA, Native American and Afghan.

The following is the analysis of ACEs and PHQ-9, substance-use disorder and self-worth scores.

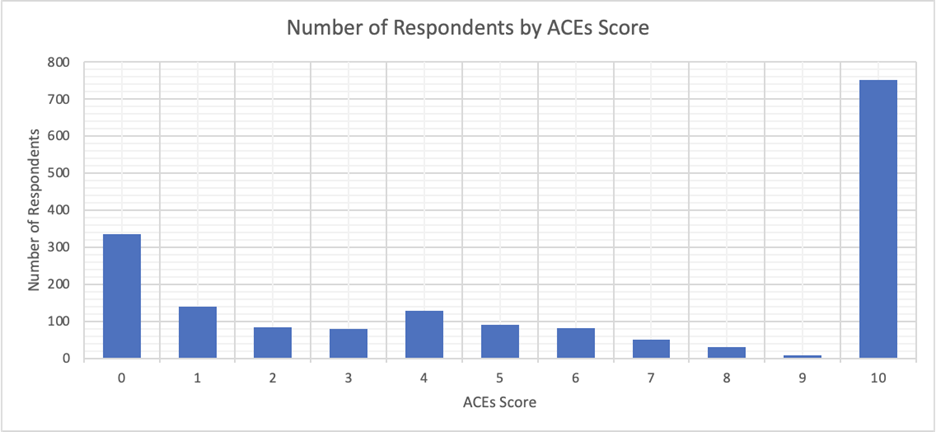

To begin with, the number of respondents for each ACEs score was calculated. This was done by adding 1 point for each negative experience. The number of ACEs determines the score (out of 10 possible points/experiences). As shown in Figure 1, the number of individuals with an ACEs score of 10 was substantially larger than the number of individuals for any other score. This may be due to inaccurate survey responses or may be an actual estimate of the represented sample’s experiences. Most likely, this may be a mixture of both inaccuracy and accuracy, with some survey respondents facing a lot of adverse experiences and others inaccurately representing their experiences. Regardless, the scores of 0, 1, 4 and 10 were most common. The scores of 7, 8 and 9 were the least common. The number of respondents with a score of 9 was very limited. This did impact other figures, as shown below.

Due to the abnormally large values of those with a score above 10, we decided to remove those with a score of 10 from the analysis of ACEs score to allow for more accurate data analysis. Before removing those with a score of 10, the MENA American community had one of the highest average ACEs scores. Although this score dropped considerably after the change, we decided to continue focusing on MENA Americans, especially considering the limited pre-existing research on that population.

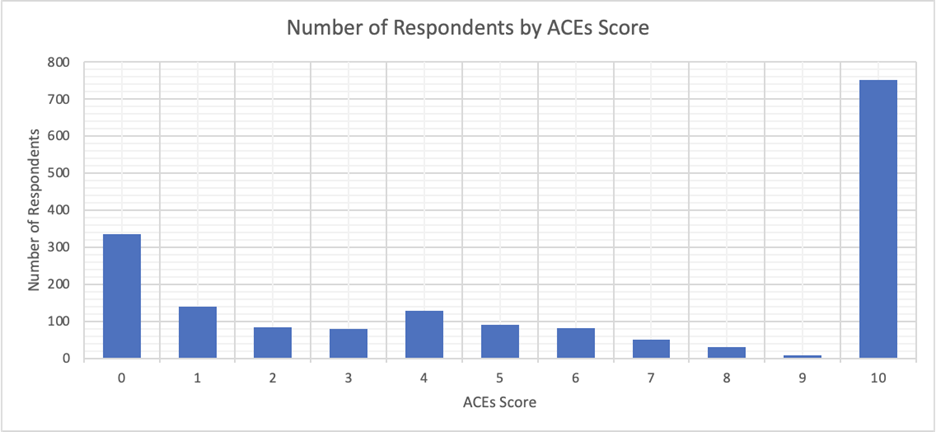

So, to analyse the impact of these ACEs scores on mental health, the average scores of indicators of mental health were calculated and plotted, as shown in Figure 2. Analysing the resulting curve, distinct relationships were observed. Firstly, with increasing ACEs scores, the substance-use disorder average score also increased while the self-worth average score decreased. In addition, PHQ-9 scores showed an interesting pattern with the highest PHQ-9 scores being found between an ACEs score of 4 and 6. After an ACEs score of 6, the PHQ-9 scores started decreasing. Although an ACEs score of 9 still had a higher PHQ-9 average score than an ACEs score of 0, this decrease impacted the relationship between ACEs and the PHQ-9, making the PHQ-9 slightly different from the other indicators of mental wellness.

To understand the role of ethnic identity in ACEs scoring, the average ACEs score for each ethnic identity was listed in Table 2. As shown below, respondents identifying as ‘White’ had the lowest average score, while members identifying as ‘Afghan’ had the highest average score, meaning that they had faced more ACEs.

| Group | Average (out of 10) |

| East Asian | 1.223 |

| South Asian | 1.446 |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 1.462 |

| Southeast Asian | 1.472 |

| White | 2.758 |

| Black or African American | 2.939 |

| Hispanic, Latino or Spanish Origin | 3.205 |

| Mixed Ethnic Identities | 3.25 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 3.286 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3.333 |

| Other Asian (Afghan) | 5.000 |

| Overall | 2.594 |

Similarly, Table 3 lists the average substance-use disorder score by ethnic-identity group. Here, ‘East Asians’ had the lowest average scores while ‘Afghans’ again had the highest average score.

| Group | Average (out of 16) |

| East Asian | 7.429 |

| Southeast Asian | 7.99 |

| White | 8.07 |

| South Asian | 8.244 |

| Hispanic, Latino or Spanish Origin | 8.254 |

| Black or African American | 8.62 |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 9.504 |

| Mixed Ethnic Identities | 9.528 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 9.786 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 9.812 |

| Other Asian (Afghan) | 10.053 |

| Overall | 9.786 |

Table 4 lists the average self-worth scores by ethnic-identity groups. With self-worth, the scores are reversed since a higher self-worth score translates into a more positive response. Respondents who identified as ‘East Asian’ again have the most positive score (or the lowest score), meaning they had the highest self-worth while those identifying as ‘Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander’ have the least positive score (or the highest score), meaning they had the lowest self-worth.

| Group | Average (out of 12) |

| East Asian | 6.411 |

| White | 6.404 |

| Black or African American | 6.261 |

| Hispanic, Latino or Spanish Origin | 6.261 |

| South Asian | 6.262 |

| Southeast Asian | 6.103 |

| Mixed Ethnic Identities | 6.07 |

| Other Asian (Afghan) | 6 |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 5.991 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 5.969 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 5.895 |

| Overall | 6.35 |

Since the data showed distinct trends between ACEs scores, and substance-use disorder and self-worth scores, respectively, these three factors were analysed for each ethnic identity group. The top five groups with the highest ACEs score and highest substance-use disorder scores, and the lowest self-worth score were surprisingly almost the exact same: MENA, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Mixed Ethnic Identities, with the exception of MENA having a lower adjusted ACEs average score. To deepen the analysis, the two groups with the highest ACEs score along with MENA were further analysed. These groups were the: Afghan American, MENA American and Native American communities.

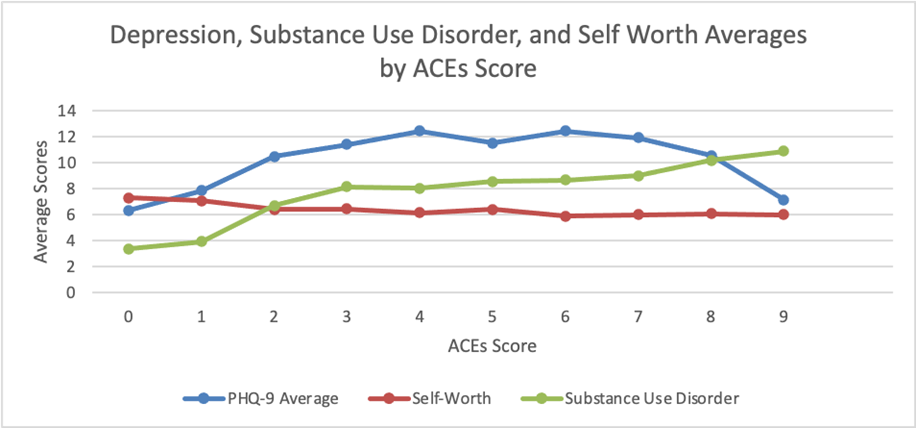

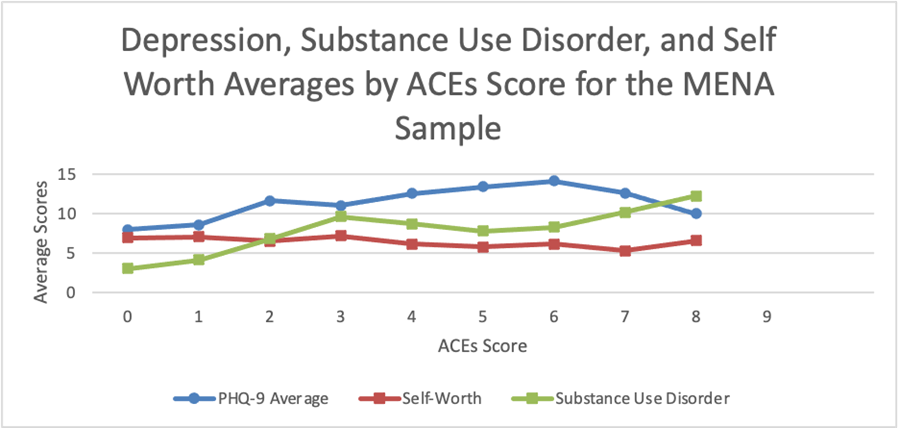

Figure 3 shows the data for the MENA sample. There is a similar shape to the data found for the overall sample. For depression, however, the MENA sample has a peak of 14.14 at an ACEs score of 6, which is substantially higher than the overall sample’s peak at an ACEs score of 6 of 12.41. While the substance-use disorder values are similar to the overall sample, the self-worth values are all lower than those of the overall sample at each ACEs score.

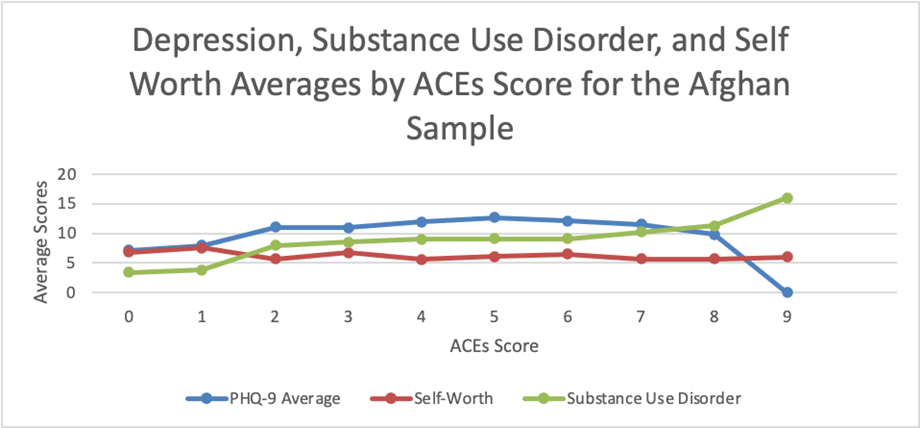

Figure 4 shows the data for the Afghan sample. The PHQ-9 values, substance-use disorder values and self-worth values are similar to the overall sample, although this sample has the highest ACEs and substance-use disorder averages.

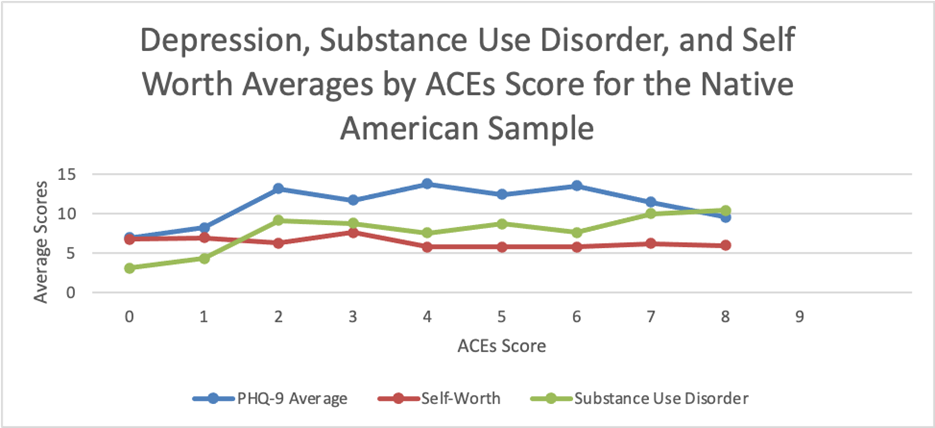

Lastly, Figure 5 shows the data for the American Indian or Alaska Native sample. For depression, it has a peak of 13.78 at an ACEs score of 4, which is higher than the overall sample’s peak at an ACEs score of 6 of 12.41. For self-worth and substance-use disorder, the scores were similar to the overall sample.

As the study demonstrates, there is a strong correlation between mental health and ACEs scores. Overall, mental health declined as ACEs scores increased. Higher ACEs scores correlated with higher substance-use disorders, lower self-worth and higher depression rates. The survey conducted showed that the represented ethnic identities of the Afghan American and Native American communities were the ones with the highest ACEs scores. These same communities, including the MENA American community, also had some of the lowest self-worth scores and highest substance-use disorder scores.

In regard to the depression rates, the PHQ-9 scores of the three samples were generally the highest among ACEs scores of 4–6 and the lowest among scores from 0–1. Specifically for ACEs scores, a score between 0–3 generally showed lower PHQ-9 scores, while scores of 4–6 was generally where the highest PHQ-9 scores lay (meaning the feelings described were felt more often, either nearly every day or every day) , and there was a decrease in the depression scores from 7 to 10 ACEs. Essentially, the graphs started low, peaked around the middle and then slightly decreased for all three samples.

The data also found that as ACEs scores increased so did substance-use disorder scores. And although self-worth was lowest among these communities, across ACEs scores, there was a very slight decrease in self-worth scores around an ACEs score of 4, which is similar to what previous studies predicted.

Research on the Native American population has indicated an extreme amount of historical trauma that is at the root of the mental health struggles faced by this community (McLeigh, 2010). Research has indicated that Native American youth report significantly more depressive symptoms than non-Hispanic White youth, revealing the extent of the problem currently (Serafini et al., 2017). Policies that have led to many Native American rights being infringed upon, resulting in a population that continues to face turmoil societally. This turmoil may play a major role in many Native Americans having high ACEs scores and thus multiple mental health struggles.

West/Central Asia has historically been an unsafe region. In addition to the generational trauma caused by violence and instability in this region, research has indicated that the mental health of children and adolescents in this area has been deteriorating (El-Gilany and Amr, 2010; Mechammil et al. 2019). There is also a large refugee population from this region, specifically the Afghan American population in recent times. These struggles may be contributing factors in both Afghan Americans and MENA Americans having disproportionately high ACEs scores, especially since many of them may have immigrated recently or have family/friends in regions with considerable instability.

Without data on these minority communities, their struggles would never come to light. This paper emphasises the importance of targeting at-risk minority groups in research efforts and in prevention/treatment efforts. Disaggregating ethnic groups can result in key focus areas coming to light, such as the issues faced by the MENA community that are not faced by the majority of the White-identifying community.

This research discussed ethnic identities that are specifically differentiated into different categories that differ from traditional ethnic-identity grouping. Therefore, most of these groups are rarely ever discussed individually. For example, nearly all traditional ethnic labelling puts all Asian countries into one category. Those with mixed identities are also never fully given a chance to identify with their entire ethnic identity and usually have to choose a single identity to identify as. Since this study emphasised each individual having a chance to express their ethnic identity by what they believe, this makes this study unique.

But this uniqueness comes at the cost of not having many comparisons by which the results can be measured. Although many articles present beneficial information on well-known ethnic communities, not many discuss identities such as the Afghan community or the Middle Eastern and North African communities. This is why there needs to be more research done on these specific ethnic identities.

Learning about Adverse Childhood Experiences of individuals with different backgrounds can provide a unique perspective into how mental health can be impacted by the environment that an individual grows up in. Policy reforms and interventions stemming from this analysis may help counter the deleterious effects of ACEs. Previous studies have found that an ACEs score above 6 as being the range associated with shortened life spans of up to 20 years (Brown et al., 2009). Interestingly, an ACEs score of 6 was found to be the score associated with the highest average PHQ-9 score in this study as well. Through obtaining such data, where the specifics on which community has high ACEs scores and what their mental health is characterised by is known, a step further can be taken by having individuals deal with their past traumatic experiences through help from mental health professionals. Getting individuals in these communities the care that they need may allow them to have more time with their loved ones or even to heal from those past traumatic experiences.

Therefore, it is crucial that research on these communities, with ethnic identity being prioritised, be continued as these are the communities that are often overlooked. This research also presents an argument for early intervention in circumstances that deal with early childhood abuse, which will lead to the reduction of the risk of having a mental illness in the later years.

This survey did have its share of limitations. Since this was an anonymous survey, we were unable to distinguish whether the answers given by participants were genuine or if the questions were answered randomly. However, since this is true of all surveys, it may not have had a large impact. The incentive of receiving a gift card for those who complete the survey first may have further promoted answering quickly without reading the questions. The incentive could also affect the motive of the individuals so that instead of answering to contribute to the research of mental health, they may have participated for the reward of the gift card. However, this is a common method used in survey research.

Due to the nature of these questions, participants may not have been completely honest about their answers. Even though the participants were reassured about the anonymity of their answers, there were many personal questions that the participants may have been hesitant to answer honestly due to a fear of having their answers revealed. However, the emphasis on anonymity may have meant that participants were not majorly impacted by this.

The accuracy of memory is another limitation. Many participants may not remember their childhood memories, or may even remember them incorrectly. And, since this survey requires the memory of traumatic events, the mechanism of ‘repressed memories’ is another limitation to take into context. Individuals who have endured abuse as children may store away these memories from consciousness as a way to shelter from the pain that they experienced (Paul, 2015). Many individuals who may have gone through traumatic childhood experiences may have repressed those memories and marked ‘No’ to questions regarding that event.

Another limitation depended on the outreach of the survey and flyer. Those students who were proficient with technology would be the ones who saw the flyer and were able to answer the survey. And, since we are Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) majors, we reached out to other primarily STEM major undergraduate students and faculty to help advertise the survey. So, even though the survey was open to all students regardless of their major, it can be assumed that a large quantity of the students may have been primarily from the STEM category.

A final limitation to be listed is the specificity of the population and the sample that this research was measuring. Ohlone College is unique in having students from the Bay Area, a region with various immigrant communities. This resulted in students from a multitude of ethnic backgrounds participating in the survey. However, since this research is looking specifically at one community college, the population and sample are very specific. Therefore, even though Ohlone College has a very diverse student body, because of its specificity as a small community college in California, it would not properly represent the various ethnic identities that this survey attempted to look at.

This study is unique both with its novel and descriptive ethnic-identity categories and with applying ethnic identities to mental health and Adverse Childhood Experiences. Our findings about the ethnic-identity groups that are majorly impacted by ACEs reveal affinity groups that may be targeted in future intervention strategies. Future research on the reasons these populations face more ACEs and on strategies that may mitigate the impacts of ACEs on these communities would be necessary.

We would like to thank Dr Laurie Issel-Tarver for her support and guidance on this project as well as Dr Sang Leng Trieu for editing our Mission Statement. We also want to thank Dr Magali Fassiotto (Stanford University School of Medicine – Office of Faculty Development and Diversity), Barbara Jerome (MPH, Stanford University School of Medicine – Office of Faculty Development and Diversity), Lisa Herron (MPH, Well-being and Equity in the World), and Hardeep Kaur (CPA, Lead Consultant at Kaiser Permanente) for reviewing and editing our research paper. Furthermore, we would like to thank the Ohlone College Inter-Club Council for providing us with the money used to purchase the survey incentive gift cards. Additionally, we would also like to thank the following professors for assisting us in advertising the survey link of our project by sharing it with their students: Dr Lisa Wesoloski, Dr Luba Voloshko, Dr Mark Barnby, Dr Sima Sarvari, Dr Margaret Lee, Dr Jennifer Hurley, Counselor Mandy Kwok-Yip, Dr Becky Gee, Professor Nabeel Atique and Professor Anh Nguyen.

Q1 We will be focusing on a sample collected from a population of Ohlone College students. The data collected will be anonymous. There will be no names or other personally identifying information collected. All data will be used strictly by our group for research purposes only and raw data will not be released to the public. Items presented include only multiple-choice questions. There is no risk to subjects taking the survey, however, some questions may be discomforting. If you no longer would like to proceed with the survey, you have the right to withdraw at any moment.

Answer Choices:

Q2 How would you describe yourself? If other, please specify.

Answer Choices:

Q3 Which category best describes you? Please click on the category.

Answer Choices:

Q4 Please provide the specifics for the category you picked for question 3 in the comment section below. (e.g. Asian – half-Chinese, half-Korean OR Middle Eastern/North African – Egyptian)

Answer Choices:

Q5 I browse the headings, pictures, chapter questions and summaries before I start reading a chapter and I look for familiar concepts as well as ideas that spark my interest as I read.

Answer Choices:

Q6 I take notes, and rewrite them, as I read my textbooks and during class lectures.

Answer Choices:

Q7 I study where it is quiet and has few distractions; I take short breaks while studying for a long period of time, I set study goals, such as the number of problems I will do or pages I will read, and I use a ‘to do’ list to keep track of completing my academic and personal activities.

Answer Choices:

Q8 I quiz myself over material that could appear on future exams and quizzes and say difficult concepts out loud in order to understand them better. I also start studying for quizzes and tests at least several days before I take them.

Answer Choices:

Q9 I study with a classmate or group and when I don’t understand something, I get help from tutors, classmates and my instructors.

Answer Choices:

Q10 In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?

Answer Choices:

Q11 In the last month, how often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems?

Answer Choices:

Q12 In the last month, how often have you felt that things were going your way?

Answer Choices:

Q13 In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?

Answer Choices:

Q14 I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others.

Answer Choices:

Q15 I feel that I have a number of good qualities.

Answer Choices:

Q16 All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure.

Answer Choices:

Q17 I wish I could have more respect for myself.

Answer Choices:

Q18 Which of the following are you experiencing (or did you experience) during COVID-19 (Coronavirus)? (check all that apply)

Answer Choices:

Q19 I feel more nervous and anxious than usual.

Answer Choices:

Q20 Before your 18th birthday, did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often swear at you, insult you, put you down, humiliate you or act in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt?

Answer Choices:

Q21 Before your 18th birthday, did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often push, grab, slap, throw something at you or ever hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured?

Answer Choices:

Q22 Before your 18th birthday, did an adult or person at least 5 years older than you ever touch or fondle you, have you touch their body in a sexual way, attempt, or actually have oral, anal or vaginal intercourse with you?

Answer Choices:

Q23 Before your 18th birthday, did you often or very often feel that no one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special, your family didn’t look out for each other, feel close to each other or support each other?

Answer Choices:

Q24 Before your 18th birthday, did you often or very often feel that you didn’t have enough to eat, had to wear dirty clothes, had no one to protect you, your parents were too drunk or high to take care of you or take you to the doctor if you needed it?

Answer Choices:

Q25 Before your 18th birthday, were your parents ever separated or divorced?

Answer Choices:

Q26 Before your 18th birthday, was your mother or stepmother often or very often pushed, grabbed, slapped, had something thrown at her, sometimes, often or very often kicked, bitten, hit with a fist, hit with something hard, or ever repeatedly hit over for at least a few minutes or threatened with a gun or knife?

Answer Choices:

Q27 Before your 18th birthday, did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic or who used street drugs?

Answer Choices:

Q28 Before your 18th birthday, was a household member depressed or mentally ill, or did a household member attempt suicide?

Answer Choices:

Q29 Before your 18th birthday, did a household member go to prison?

Answer Choices:

Q30 In the PAST 12 MONTHS, how often have you used any tobacco product (for example, cigarettes, e-cigarettes, cigars, pipes or smokeless tobacco)?

Answer Choices:

Q31 In the PAST 12 MONTHS, how often have you had drinks containing alcohol in one day?

Answer Choices:

Q32 In the PAST 12 MONTHS, how often have you used any drugs including marijuana, cocaine or crack, heroin, methamphetamine (crystal meth), hallucinogens, ecstasy/MDMA?

Answer Choices:

Q33 In the PAST 12 MONTHS, how often have you used any prescription medications just for the feeling, more than prescribed or that were not prescribed for you? Prescription medications that may be used this way include: Opiate pain relievers (for example, OxyContin, Vicodin, Percocet, Methadone); Medications for anxiety or sleeping (for example, Xanax, Ativan, Klonopin); Medications for ADHD (for example, Adderall or Ritalin)

Answer Choices:

Q34 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Little interest or pleasure in doing things?

Answer Choices:

Q35 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

Answer Choices:

Q36 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much?

Answer Choices:

Q37 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Feeling tired or having little energy?

Answer Choices:

Q38 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Poor appetite or overeating?

Answer Choices:

Q39 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Feeling bad about yourself – or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down?

Answer Choices:

Q40 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television?

Answer Choices:

Q41 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed? Or so fidgety or restless that you have been moving a lot more than usual?

Answer Choices:

Q42 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or thoughts of hurting yourself in some way?

Answer Choices:

Q43 Lastly, please provide your email address (Most preferably student email) to receive a gift card. Type in N/A if you do not want to receive a gift card.

Answer Choices:

Q1 We will be focusing on a sample collected from a population of Ohlone College students. The data collected will be anonymous. There will be no names or other personally identifying information collected. All data will be used strictly by our group for research purposes only and raw data will not be released to the public. Items presented include only multiple-choice questions. There is no risk to subjects taking the survey, however, some questions may be discomforting. If you no longer would like to proceed with the survey, you have the right to withdraw at any moment.

Answer Choices:

Q2 How would you describe yourself? If other, please specify.

Answer Choices:

Q3 Which category best describes you? Please click on the category.

Answer Choices:

Q4 I browse the headings, pictures, chapter questions, and summaries before I start reading a chapter and I look for familiar concepts as well as ideas that spark my interest as I read.

Answer Choices:

Q5 I take notes, and rewrite them, as I read my textbooks and during class lectures.

Answer Choices:

Q6 I study where it is quiet and has few distractions, I take short breaks while studying for a long period of time, I set study goals, such as the number of problems I will do or pages I will read, and I use a ‘to do’ list to keep track of completing my academic and personal activities.

Answer Choices:

Q7 I quiz myself over material that could appear on future exams and quizzes and say difficult concepts out loud in order to understand them better. I also start studying for quizzes and tests at least several days before I take them.

Answer Choices:

Q8 I study with a classmate or group and when I don’t understand something, I get help from tutors, classmates and my instructors.

Answer Choices:

Q9 In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?

Answer Choices:

Q10 In the last month, how often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems?

Answer Choices:

Q11 In the last month, how often have you felt that things were going your way?

Answer Choices:

Q12 In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?

Answer Choices:

Q13 I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others.

Answer Choices:

Q14 I feel that I have a number of good qualities.

Answer Choices:

Q15 All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure.

Answer Choices:

Q16 I wish I could have more respect for myself.

Answer Choices:

Q17 Which of the following are you experiencing (or did you experience) during COVID-19 (coronavirus)? (check all that apply)

Answer Choices:

Q18 I feel more nervous and anxious than usual.

Answer Choices:

Q19 Before your 18th birthday, did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often swear at you, insult you, put you down, humiliate you or act in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt?

Answer Choices:

Q20 Before your 18th birthday, did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often push, grab, slap, throw something at you or ever hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured?

Answer Choices:

Q21 Before your 18th birthday, did an adult or person at least 5 years older than you ever touch or fondle you, have you touch their body in a sexual way, attempt, or actually have oral, anal or vaginal intercourse with you?

Answer Choices:

Q22 Before your 18th birthday, did you often or very often feel that no one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special, your family didn’t look out for each other, feel close to each other, or support each other?

Answer Choices:

Q23 Before your 18th birthday, did you often or very often feel that you didn’t have enough to eat, had to wear dirty clothes, had no one to protect you, your parents were too drunk or high to take care of you or take you to the doctor if you needed it?

Answer Choices:

Q24 Before your 18th birthday, were your parents ever separated or divorced?

Answer Choices:

Q25 Before your 18th birthday, was your mother or stepmother often or very often pushed, grabbed, slapped, had something thrown at her, sometimes, often or very often kicked, bitten, hit with a fist, hit with something hard, or ever repeatedly hit over for at least a few minutes or threatened with a gun or knife?

Answer Choices:

Q26 Before your 18th birthday. did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic, or who used street drugs?

Answer Choices:

Q27 Before your 18th birthday, was a household member depressed or mentally ill, or did a household member attempt suicide?

Answer Choices:

Q28 Before your 18th birthday, did a household member go to prison?

Answer Choices:

Q29 In the PAST 12 MONTHS, how often have you used any tobacco product (for example, cigarettes, e-cigarettes, cigars, pipes or smokeless tobacco)?

Answer Choices:

Q30 In the PAST 12 MONTHS, how often have you had drinks containing alcohol in one day?

Answer Choices:

Q31 In the PAST 12 MONTHS, how often have you used any drugs including marijuana, cocaine or crack, heroin, methamphetamine (crystal meth), hallucinogens, ecstasy/MDMA?

Answer Choices:

Q32 In the PAST 12 MONTHS, how often have you used any prescription medications just for the feeling, more than prescribed or that were not prescribed for you? Prescription medications that may be used this way include: Opiate pain relievers (for example, OxyContin, Vicodin, Percocet, Methadone); Medications for anxiety or sleeping (for example, Xanax, Ativan, Klonopin); Medications for ADHD (for example, Adderall or Ritalin)

Answer Choices:

Q33 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Little interest or pleasure in doing things?

Answer Choices:

Q34 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

Answer Choices:

Q35 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much?

Answer Choices:

Q36 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Feeling tired or having little energy?

Answer Choices:

Q37 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Poor appetite or overeating?

Answer Choices:

Q38 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Feeling bad about yourself – or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down?

Answer Choices:

Q39 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television?

Answer Choices:

Q40 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed? Or so fidgety or restless that you have been moving a lot more than usual?

Answer Choices:

Q41 How often have you been bothered by the following over the past 2 weeks: Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or thoughts of hurting yourself in some way?

Answer Choices:

Q42 Lastly, please provide your email address (Most preferably student email) to receive a gift card. Type in N/A if you do not want to receive a gift card.

Answer Choices:

About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study |Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDC. (2022, March 17). https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html

APA (American Psychological Association). (n.d.). ‘Resilience’, APA Dictionary of Psychology, available at: https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience, accessed 18 April 2023.

Anda, R. F., C. L. Whitfield, V. J. Felitti, D. Chapman, V. J. Edwards, S. R. Dube and D. F. Williamson (2002), ‘Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression’, Psychiatric Services, 53 (8), 1001–09.

Assini-Meytin, L. C., R. L. Fix, K. M. Green, R. Nair and E. J. Letourneau (2022), ‘Adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and risk behaviors in adulthood: Exploring sex, racial, and ethnic group differences in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 15 (3), 833–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-021-00424-3

Awad, G. H., M. Kia-Keating and M. M. Amer, 2019. ‘A model of cumulative racial–ethnic trauma among Americans of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) descent’, American Psychologist, 74, 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000344

Awad, G. H., N. N. Abuelezam, K. J. Ajrouch and M. J. Stiffler, 2022. ‘Lack of Arab or Middle Eastern and North African health data undermines assessment of health disparities’, Am J Public Health, 112, 209–12. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306590

Brockie, T. N., G. Dana-Sacco, G. R. Wallen, H. C. Wilcox and J. C. Campbell, (2015), ‘The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to PTSD, depression, poly-drug use and suicide attempt in reservation-based Native American adolescents and young adults’, American Journal of Community Psychology, 55 (3), 411–21, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9721-3

Brown, D. W., R. F. Anda, Tiemeier, H., V. J. Felitti, V. J. Edwards, J. B. Croft and Giles, W. H. (2009), ‘Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality’. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37 (5), 389–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.021

CDC. (2022, October 5). Disease of the Week—Substance Use Disorders (SUDs). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/dotw/substance-use-disorders/index.html

Crandall, A., J. R. Miller, Cheung, A., L. K. Novilla, Glade, R., M. L. B. Novilla, B. M. Magnusson, B. L. Leavitt, M. D. Barnes and C. L. Hanson, (2019), ‘ACEs and counter-ACEs: How positive and negative childhood experiences influence adult health’, Child Abuse and Neglect, 96, 104089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104089

Dube, S. R., R. F. Anda, V. J. Felitti, D. P. Chapman, D. F. Williamson and W. H. Giles (2001), ‘Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: Findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences study’, JAMA, 286 (24), 3089–96.

Dube, S. R., R. F. Anda, V. J. Felitti, V. J. Edwards and J. B. Croft (2002a), ‘Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult’, Addictive Behaviors’, 27 (5), 713–25.

Dube, S. R., R. F. Anda, V. J. Felitti, V. J. Edwards and D. F. Williamson (2002b), ‘Exposure to abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction among adults who witnessed intimate partner violence as children: Implications for health and social services’, Violence and Victims, 17 (1), 3–17.

Dube, S. R., V. J. Felitti, M. Dong, D. P. Chapman, W. H. Giles and R. F. Anda, . (2003), ‘Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The adverse childhood experiences study’, Pediatrics, 111 (3), 564–572.

El-Gilany, A.-H. and M. Amr, (2010), Child and adolescent mental health in the Middle East: an overview. Middle East Journal of Family Medicine, 8 (8), 12–18.

Felitti, V. J., R. F. Anda, D. Nordenberg, D. F. Williamson, A. M. Spitz, V. Edwards and J. S. Marks (1998), ‘Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study’. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14 (4), 245–258

Kalmakis, K. A. and G. E. Chandler. (2014), ‘Adverse childhood experiences: Towards a clear conceptual meaning’. Journal of Advanced Nursing 70 (7), 1489–1501. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12329.

Karatekin, C. (2017), ‘Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), stress and mental health in college students’. Stress and Health, 34 (1), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2761

Kroenke, K., R. L. Spitzer and J. B. W. Williams (2001), ‘The PHQ-9 – Validity of a brief depression severity measure’, Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606-13.

Lee, R. D. and J. Chen (2017), ‘Adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and excessive alcohol use: Examination of race/ethnicity and sex differences’, Child Abuse and Neglect, 69, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.004

Leza, L., S. Siria, J. J. López-Goñi and J. Fernández-Montalvo (2021), ‘Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and substance use disorder (SUD): A scoping review’, Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 221, 108563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108563

Maghbouleh, N., Schachter, A., R. D. Flores, (2022), ‘Middle Eastern and North African Americans may not be perceived, nor perceive themselves, to be White’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119, e2117940119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2117940119

Marriott, C., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. and Harrop, C. (2014), ‘Factors promoting resilience following childhood sexual abuse: a structured, narrative review of the literature’, Child Abuse Review (Chichester, England: 1992), 23 (1), 17–34, https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2258

McLeigh, J. D. (2010), ‘What are the policy issues related to the mental health of Native Americans?’ Am J Orthopsychiatry 80, 177–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01021.x

McNeely, J., L. T. Wu, Subramaniam, G., Sharma, G., L. A. Cathers, et al. (2016), ‘Performance of the tobacco, alcohol, prescription medication, and other substance use (taps) tool for substance use screening in primary care patients. Annals of Internal Medicine, in press.

Mechammil, M., Boghosian, S., R. A. Cruz, (2019), ‘Mental health attitudes among Middle Eastern/North African individuals in the United States’, Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 22, 724–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2019.1644302

Merrick, M. T., K. A. Ports, D. C. Ford, T. O. Afifi, E. T. Gershoff and A. Grogan-Kaylor (2017), ‘Unpacking the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health’, Child Abuse and Neglect, 69, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.016

Mersky, J. P., J. Topitzes and A. J. Reynolds (2013), ‘Impacts of adverse childhood experiences on health, mental health, and substance use in early adulthood: a cohort study of an urban, minority sample in the U.S’, Child Abuse and Neglect, 37 (11), 917–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.011

Mignon, S. I. and W. M. Holmes (2013), ‘Substance abuse and mental health issues within native american grandparenting families’, Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 12 (3), 210–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2013.798751

Mueller, S. C., G. De Cuypere and G. T’Sjoen (2017), ‘Transgender research in the 21st century: A selective critical review from a neurocognitive perspective, American Journal of Psychiatry, 174 (12), 1155–62. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17060626

Paul, M. (2015), ‘How traumatic memories hide in the brain, and how to retrieve them’, North-Western News, 18 August 2015, https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2015/08/traumatic-memories-hide-retrieve-them

PolicyLink (n.d.) ‘An equity profile of the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area region’ PolicyLink, Available at: https://www.policylink.org/research/an-equity-profile-of-nine-county-san-francisco (accessed 7.21.22),

Rosenberg, M. (1965), Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sahle, B. W., N. J. Reavley, W. Li, A. J. Morgan, M. B. H. Yap, A. Reupert and A. F. Jorm, (2022), ‘The association between adverse childhood experiences and common mental disorders and suicidality: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses’, European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31 (10), 1489–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01745-2

Schilling, E. A., R. H. Aseltine Jr. and S. Gore, (2007), ‘Adverse childhood experiences and mental health in young adults: a longitudinal survey’, BMC public health, 7, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-30

Serafini, K., D. M. Donovan, D. C. Wendt, Matsumiya, B., C. A. McCarty, (2017), ‘A comparison of early adolescent behavioral health risks among urban American Indians/Alaska natives and their peers’, Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res 24, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.2402.2017.1

Strauss, P., A. Cook, S. Winter, V. Watson, D. Wright Toussaint and A. Lin, (2020), ‘Mental health issues and complex experiences of abuse among trans and gender diverse young people: Findings from trans pathways’, LGBT Health, 7 (3), 128–36. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2019.0232

Thoits, P. A. (2010), ‘Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications’, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51 (1_suppl), S41–S53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383499

World Population Review, (n.d.), ‘What percentage of the population is transgender 2022’ Available at: https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/transgender-population-by-state (accessed 21 July 2022)

Adverse Childhood Experiences: Childhood events, varying in severity and often chronic, occurring in a child’s family or social environment that cause harm or distress, thereby disrupting the child’s physical or psychological health and development (Kalankis et. al, 2014).

CDC-Kaiser ACE Study: ‘The CDC-Kaiser Permanente adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study is one of the largest investigations of childhood abuse and neglect and household challenges and later-life health and well-being. The original ACE study was conducted at Kaiser Permanente from 1995 to 1997 with two waves of data collection. Over 17,000 Health Maintenance Organization members from Southern California receiving physical exams completed confidential surveys regarding their childhood experiences and current health status and behaviors.’ (CDC, n.d.).

Resilience: Resilience is the process and outcome of successfully adapting to difficult or challenging life experiences, especially through mental, emotional and behavioral flexibility, and adjustment to external and internal demands (American Psychological Association, n.d.).

Substance Use Disorder: A treatable, chronic disease characterized by a problematic pattern of use of substances leading to impairments in health, social function and control over substance use (CDC, n.d.).

To cite this paper please use the following details: Samuel, C. et al. (2023), 'The Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences on the Mental Health Statuses

of Students Across Various Ethnic Identities', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 16, Issue 1, https://reinventionjournal.org/article/view/1190. Date accessed [insert date].

If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal@warwick.ac.uk.